Introduction

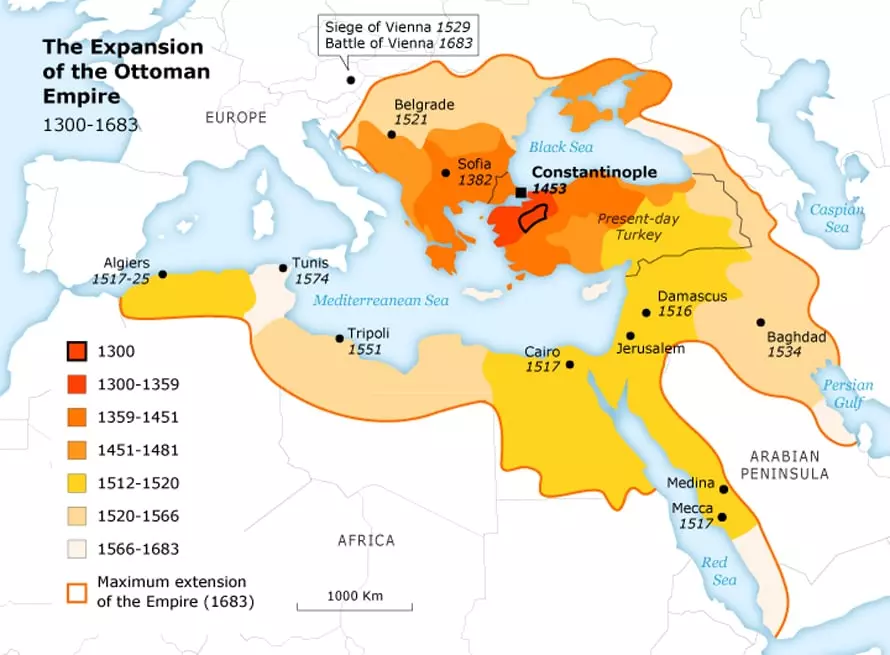

The Ottoman beylik was the successor of the Byzantine Empire after Mehmed II the ‘Conquerer’ (1432-1481) conquered Constantinople in 1453.

Ottoman territorial expansion continued under the successors of Mehmed II, especially Selim I (also known as ‘The Cruel’ and ‘The Brave’, 1470-1520) and Suleiman the Magnificent (‘The Lawgiver’, 1494-1566). After Ottoman expansion reached central Europe, the Ottomans concerned themselves with the east and the south, especially the Arab world.

Following the ‘Shiite threat’ – which, under the (Turkic) Safavid dynasty, gave rise to messianic expectations in Turkish communities abandoned by the increasingly bureaucratic Ottoman Empire – Selim I stabilized the borders with Persia in 1514 through his victory in the battle of Chaldiran. The Arab conquests of Selim I paved the path to Egypt and allowed him to seize the title of Caliph, a title that belonged to the ‘House of Osman’ until the abolition of the caliphate in 1924.

The Battle of Vienna, 1683

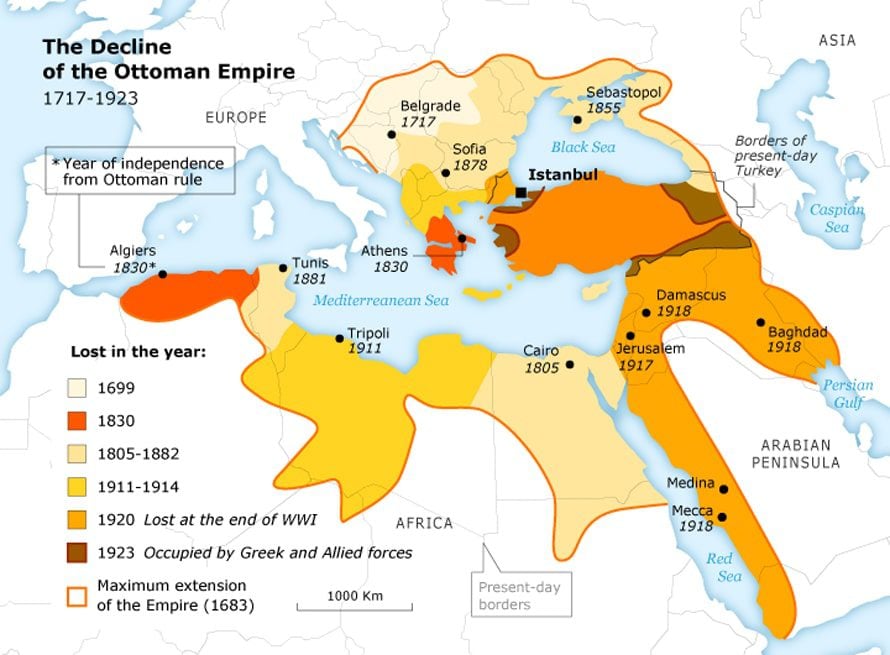

At the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th, the Ottoman Empire experienced violent internal rebellions known as the Jelali revolts and financial crises that led to riots, even in the capital. Many sultans were dethroned and some killed. The Ottoman failure to conquer Vienna in 1683 made Austria a great Central European power and shook the Ottoman presence in Europe. This was followed by a series of defeats in Europe and the Caucasus (the latter was the target of Russian expansion).

New Order

The year 1789, during which Selim III (1761-1808) was enthroned, was crucial for the Ottoman Empire. As it could not remain a Nizam-i Alem (Universal Order), the empire had to adopt a Nizam-i Cedid (New Order) that imitated the administrative, military, economic, and legal models of the European states to ensure its survival. Although Selim III was killed in 1808, following a revolt of the Janissaries (a former elite corps that was a real obstacle to changes), reforms did not stop. The reforms were followed by the Tanzimat (reorganizations), beginning in 1839.

Decline of the Ottoman Empire

According to historian Selim Deringil, the reforms of the Tanzimat planned during the reign of Mahmud II (1808-1839) and implemented during the reign of Abdülmecid I (1839-1861) founded the modern Turkish state and allowed the integration of the Ottoman Empire into Europe. Although the Ottoman Empire was able to confront Russia in the Crimean War (1853-1856), thanks to its alliance with France and Great Britain, it had to go it alone in a new war in 1877-1878, which gradually reduced the Ottoman presence in the Balkans (in the context of the emergence of nationalism and the quest for Greek and Bulgarian independence, among others).

In the wake of these wars, the Constitution promulgated by Sultan Abdülhamid II for the sole purpose of convincing the European forces of his sincerity in implementing the reforms was suspended. Furthermore, the Parliament was dissolved, and the architect of the reforms, Midhat Pasha (lived 1822-1884) – who was accused of killing Sultan Abdülaziz in 1876 – was assassinated in prison in Taif in Saudi Arabia.

The long reign of Abdülhamid II (1876-1909), called ‘The Crimson Sultan’ by his opponents, was meant to be a restoration; the sultan was authoritarian, Westernized, modernized, and Islamized all at one time. His reign ended with the Young Turk Revolution, following the proclamation of the Committee of Union and Progress (or Young Turks), a secret society that had, since 1906, been under the control of young Ottoman officers who had served in the Balkans and some nationalists, such as Bahaeddin Shakir (1874-1922) and Nazim Bey (1870-1926) of Thessaloniki. Bey was hanged in Ankara in 1926 after an attempted assassination of Atatürk.

After the restoration of the Constitution in July 1908 and the beginnings of an atmosphere described by historian François Georgeon as the ‘drunkenness of freedom’, the Committee of Union and Progress gradually constructed a power based on single-party rule (from 1913). The period between 1908 and 1913 witnessed the radicalization of the Committee of Union and Progress – which considered itself the ‘Spirit of the State’ and the ‘Kaaba of Freedom’ – and the increase of the power of Turkish nationalism.

The fraternization between imams, priests, and rabbis during their celebration of ‘freedom’ in July 1908, and the political and cultural effervescence experienced by many Ottoman cities, gradually faded, making way for the principle of ‘Order and Discipline’ that the ideologists of the unionist movement justified by the need to confront ‘the doctrine of human rights spreading like a germ’.

The 'Turkist' Movement

The disciplinary clamp down associated with the ‘Turkist’ movement is obvious as of 1905-1906 in the internal correspondence of the Central Committee of the Committee of Union and Progress (C.U.P.). It was, however, part of a process marked by an urgency that can be explained primarily by the international context – the Bulgarian proclamation of independence, the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary, the Albanian insurrection and independence, the occupation of Tripoli of Barbary by Italy, and the 1912 defeat by the coalition of the Balkan States – which created a sense of humiliation and a panic among the Unionists.

A columnist at the time explains: ‘We have already lost Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Crete, and now we are about to lose Rumelia, and in two years we will lose Istanbul. Holy Islam and the respectable Ottoman Empire will move to Kayseri, which will become our capital, and Mersin our port, and Armenia and Kurdistan our neighbours, and the Muscovites our lords.’

However, the dizzying chronology of the internal policy of the Ottoman capital – marked by the revolt against the young unionist officers (Young Turks) in Istanbul in 1909 who ‘insult our religion’; the weakening of the unionist government and its overthrow on 12 July 1912; and the emergence of a secret competing military committee – made the unionists feel as though they were backed into a corner. The coup d’état of January 1913 organized by Enver Pasha, one of the two iconic officers of the 1908 proclamation, resulted from these events.

Three Pashas

The immediate consequence was the nomination of Mahmud Shevket Pasha (1856-1913), the general who formed the Army of Action during the 1909 uprising in Istanbul, to head a new government. The mysterious assassination of this powerful man (11 June 1913), who tried to protect the independence of the army from the unionists, gave the committee the opportunity to suppress political pluralism and execute or exile the leaders of the liberal opposition.

The one-party regime that he established marks the advent of the triumvirate of the ‘Three Pashas’, Djemal (1872-1922), Enver (1881-1922), and Talaat (1874-1921). The first two had a career in the military, and the latter was trained in a military school and was an officer in the telegraph service.