Introduction

Turkey, while not a large supplier of energy, is a major demand centre in the MENA region and a net importer of all three major fossil fuel sources [1]. The country also has significant geostrategic importance. This stems in large measure from its geographic location and its military capability. Turkey’s membership in NATO goes back to the Cold War and it today maintains the second-largest standing army in the security bloc. Its proximity to the former Soviet Union made it an important country to include in the NATO alliance.

With regard to energy, geography is primary as Turkey controls the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits – the Turkish straits linking the Black Sea with the Mediterranean, through which an average of 3 million barrels of oil per day (mb/d) were transported in 2013 – hence controlling a choke point on one of Russia’s three crude oil maritime export routes.

Furthermore, the fact that Turkey shares land borders with Iraq, Iran, Syria, Armenia and Georgia to its east, and Bulgaria and Greece to its west means the country is uniquely placed to link supply centres in the Middle East with energy markets in Europe. The possibility of Turkey ultimately providing an alternative export pipeline system to Russian pipeline gas looms large on the global energy scene. This possibility ensures that Turkey maintains a prominent position in any discussion of major supply, demand or transit players.

Oil and Gas: Limited Supply

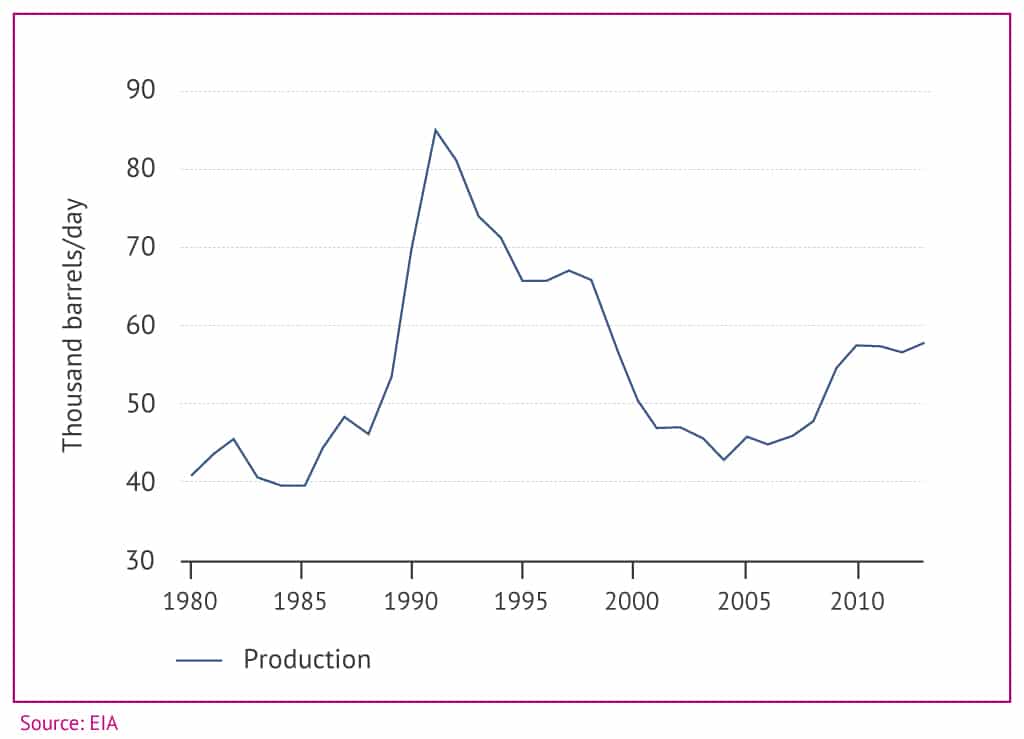

Turkey may not be a significant supply centre but it is a significant oil and gas demand centre in the MENA region, making it an export destination for oil from major regional players in Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia as well as extra-regional players in Russia, Kazakhstan and Africa. Furthermore, it is a compelling transport route, along which much more oil transits than is consumed. Turkey has conventional [2] proven oil reserves of 295 million barrels (or about 4.5 days’ worth of world oil production). These are mostly located in the Batman and Adiyaman provinces in the south-east (which is also where most of Turkey’s oil production occurs), with additional deposits found in Thrace in the north-west. Turkey’s oil production peaked in 1991 at 85,000 barrels per day (bbl/d), but declined over the next 13 years to a low of 43,000bbl/d before experiencing a modest revival in early 2004.

Yet although Turkey’s production of liquid fuels has increased slightly since 2004, it falls far short of the country’s annual needs, with 2012 production (nearly 60,000bbl/d) providing for only about 10% of national consumption.

Proven natural gas reserves in Turkey amount to 6.17 billion cubic metres (BCM). The country produces a very small amount of natural gas, with total production amounting to 22 billion cubic feet (BCF) in 2012 and providing less than 2% of consumption. Turkiye Petrolleri A.O. (TPAO), BP, and Royal Dutch Shell account for most of the country’s natural gas production. In recent years, a number of natural gas fields have been brought on line in the Black Sea, including Akçakoca, East Ayazli, Akkaya and Ayazli. Despite the limited proven reserves, gas exploration efforts have increased, particularly offshore. Supermajor Royal Dutch Shell is poised to spend $300 million on an exploration programme in the Turkish Black Sea, and ExxonMobil, Chevron and Petrobras have ongoing exploration programmes there. Exploration for unconventional (shale) gas reserves has also increased. Despite the ongoing struggle for Kurdish autonomy by the PKK and potential spillover from the war in Syria, Shell has an agreement with TPAO for shale gas exploration, with the Turkish firm taking a 70% share of production and Shell receiving 30%.

Oil and Gas: Growing Demand

After Israel, Turkey is the only member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in the MENA region. Within this advanced economic block, Turkey is forecast to see the highest growth in energy demand of all OECD countries. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy use will continue to grow at an annual rate of around 4.5% from 2015 to 2030, approximately doubling over the next decade. The IEA expects electricity demand to increase at an even faster pace (electricity is discussed further here). Turkey’s petroleum product consumption increased relatively slowly overall in the past decade, though demand for automotive fuels and jet fuel rose more strongly. Taxes and changes from oil-fired to natural gas-fired power plants suppressed overall oil demand in this period.

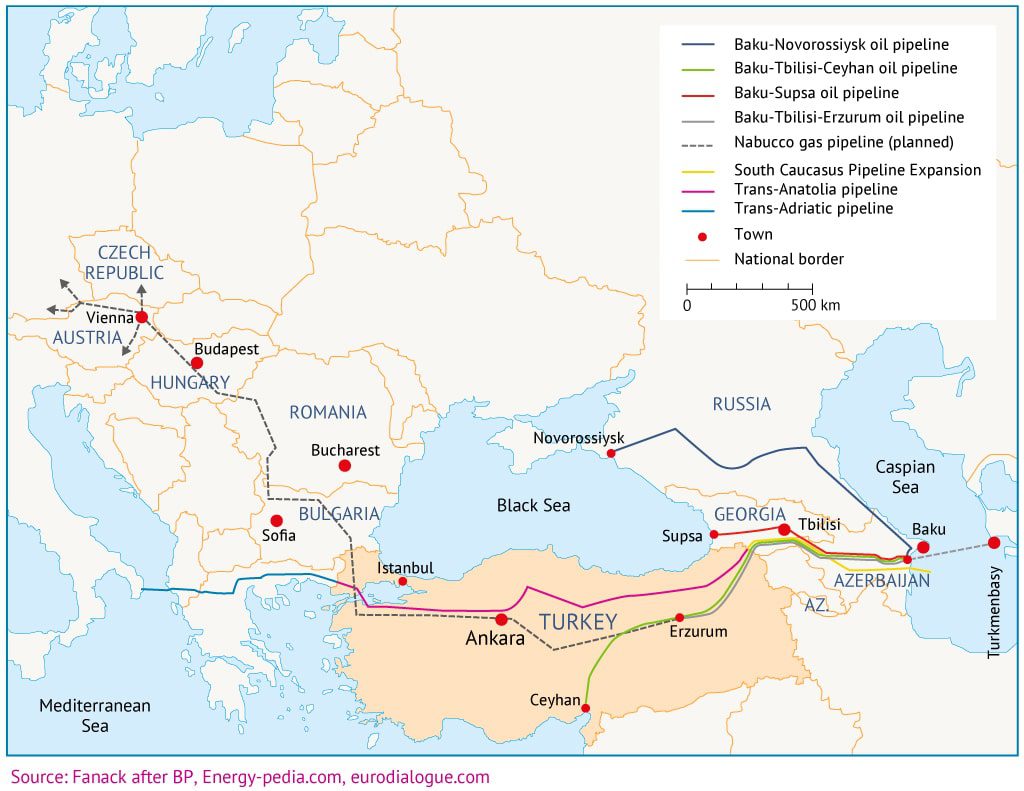

The modest change is illustrated by noting that total consumption in 2011 was 706,000bbl/d, up from 619,000bbl/d in 2001. In 2013, Turkey’s total liquid fuels consumption averaged 734,800bbl/d. More than 90% of crude oil consumption and significant quantities of petroleum products came from imports. Turkey has various crude oil pipelines that bring oil from neighbouring Iran, Iraq and Azerbaijan (more on pipelines in Turkey can be found in subsection 2.2.). Crude oil that is not used by Turkish refineries is transported to other countries via oil export terminals such as Ceyhan (see map 2).

As with oil, Turkey is a large consumer of natural gas but a small producer. The overall strong growth of the Turkish economy, as well as new power plants being gas fired rather than oil fired (about 60% of natural gas is used for electricity generation), is driving consumption. Consumption has increased by a factor of more than 10 in the past 20 years, and has nearly tripled in the past decade. In 2011, Turkey’s electric power sector accounted for just under half (48%) of the country’s natural gas use. The industrial and residential sectors each accounted for approximately 20% (with 6% going to commercial uses, 4% going to other uses and 1% going to transport). Natural gas demand peaks in the winter months, when natural gas use for power generation and space heating is highest. Demand during the winter months can be double the demand during the summer months, a common seasonal pattern in high gas use countries.

Most of Turkey’s natural gas imports arrive in the country via pipeline, including those from Russia (56%), Iran (18%) and Azerbaijan (8%). The majority of Russian gas arrives via the Blue Stream pipeline, although sizeable volumes also reach the large population centres in and around Istanbul via the Bulgaria-Turkey pipeline. Turkey received about 290BCF of Iranian natural gas via the Tabriz-Doğubayazit pipeline in 2012. An additional 118BCF arrived from Azerbaijan via the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) pipeline in the same year. Turkey also imports liquefied natural gas (LNG) amounting to 16% of total imports, particularly from Algeria, Qatar, Egypt, Nigeria and Norway. LNG volumes arrive at the country’s two terminals, Marmara Ereğlisi in Tekirdağ and Aliağa in Izmir.

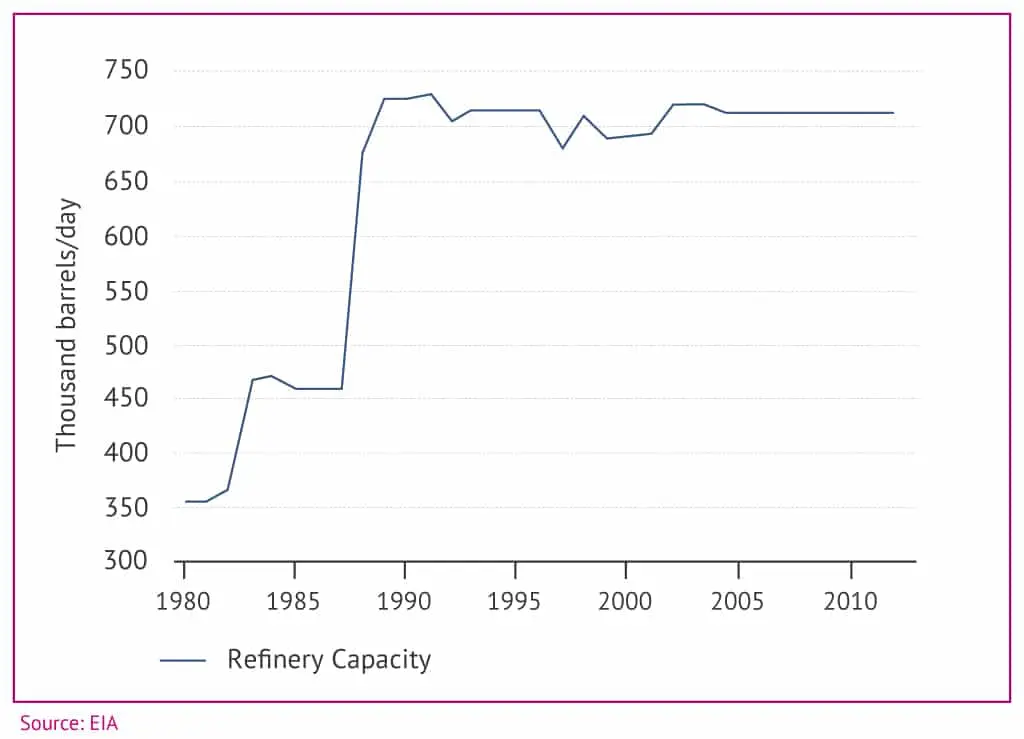

As of 1 January 2014, Turkey had six refineries with a combined processing capacity of 714,275bbl/d, according to Oil & Gas Journal (see map 2 for the locations of key refineries). The majority of this refining capacity was built up in the 1980s (see figure 3).

Tüpraş is Turkey’s dominant refining firm, operating more than 85% of the total refining capacity as well as controlling 59% of the total petroleum products’ storage capacity. Given demand – and demand growth – in Turkey, there is room for increased crude oil refining capacity. Currently, Turkey imports some products, particularly diesel, to make up for inadequate refinery output. A smaller amount of products for which refinery output exceeds local demand is exported (mostly gasoline).

Oil and gas transit potential: the “Southern Corridor”

In addition to the oil pipelines in map 2 (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan 1.2mb/d and Kirkuk-Ceyhan 1.4mb/d) relevant for domestic consumption of oil as well as export capacity, natural gas transit and export capacity is of significant interest to the global energy demand and supply picture, given Turkey’s strategic location. To date, however, the requisite investment has not materialized although there are plans to increase transit capacity. While Turkey enjoyed considerable excess import capacity a few years ago, this has eroded as most of the pipeline capacity is now used to meet domestic demand, putting pressure on the country’s function as a gas transit state. BOTAŞ, Turkey’s state-owned oil and gas company, dominates the gas transit sector and, all being equal, will likely be a key player in any future pipeline endeavours. An important aspect of the interest in and near-term urgency of realizing Turkey’s gas transit potential is Europe’s import relationship with Russian gas.

Russia is the world’s largest holder of proven gas reserves and as such is the primary supplier of European markets. The reliability of Russia as a supplier has been called into question on several occasions over rows between the governments in Ukraine and Moscow. The result has been gaps in supply to Western markets.An important aspect of the interest in and near-term urgency of realizing Turkey’s gas transit potential is Europe’s import relationship with Russian gas. Russia is the world’s largest holder of proven gas reserves and as such is the primary supplier of European markets. The reliability of Russia as a supplier has been called into question on several occasions over rows between the governments in Ukraine and Moscow. The result has been gaps in supply to Western markets.

Russia supplies around 30% (5.7 trillion cubic feet, TCF) of Europe’s consumption volume, with a significant amount flowing through Ukraine. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that 16% (3.0TCF) of the total natural gas consumed in Europe passed through Ukraine’s pipeline network in 2012, based on data reported by Gazprom and Eastern Bloc Energy. Two major pipeline systems carry Russian gas through Ukraine to Western Europe: the Bratstvo (Brotherhood) and Soyuz (Union) pipelines (see map 3).

In the past, as much as 80% of Russian natural gas exports to Europe transited Ukraine. This number has fallen to 50%-60% since the Nord Stream pipeline, a direct link between Russia and Germany under the Baltic Sea, came online in 2011 (see map 3). Russia has hence sought to replicate its success in the north with a southern equivalent in the Black Sea linking Russia with Bulgaria, called South Stream. If successful, the project would dramatically reduce dependence on Ukraine as a transit country.

However, with the ongoing crisis in Ukraine and sanctions imposed against Russia by Western governments, the South Stream project has unsurprisingly come under pressure. The EU has asked member states to stop the construction of parts of the pipeline connecting Russia with Bulgaria, effectively terminating the pipeline. Russian President Vladimir Putin has commented that “Russia can’t start building an underwater pipeline and stop at Bulgaria”. Gazprom’s Chief Executive Officer Alexey Miller later affirmed to reporters in Ankara that “the project is over”.

Gazprom had spent 487.5 billion roubles ($9.4 billion) in the last three years on South Stream and upgrading the Russian pipelines that would have supplied it, according to bond filings. Some of that work can be used for a separate link to Turkey. Since the cancellation of South Stream, Russia will concentrate on supplying gas to Turkey through the Blue Stream pipeline, increasing deliveries by 3BCM a year and offering a 6% discount from 1 January 2015, according to President Putin.

Later in January, Gazprom introduced a plan to build the so-called “Turk Stream” pipeline. Gazprom CEO Miller said the new pipeline would consist of four lines of 15.75BCM each, with the first one to supply Turkey only (no comment was given regarding the destination of the other three lines). For reference, gas lines to Turkey from Russia through existing routes numbered imports of 27.4BCM in 2014. The first line will be laid under the Black Sea to deliver gas to Turkey’s European province of Thrace, a route through which Turkey currently receives 14 BCM/y already. Miller added that Russia and Turkey would sign an agreement to build the pipeline in the second quarter of 2015. Gazprom has still to reveal the estimated cost of the project. If the EU were to tap this new version of South Stream, it would have to build its own link to the proposed pipeline to Turkey in order to get Russian gas bypassing Ukraine.

However, the failure of South Stream and the speculative nature of Turk Stream means that supply routes through Ukraine remain in play and the present diplomatic row will serve to increase emphasis on what has been termed the “Southern Corridor”: the pipeline route through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. The map below illustrates this corridor in the main by means of the pipeline route under development by BP and others, which aims to connect the Shah Deniz (I and II) gas fields in the Caspian with European markets.

The pipelines are the South Caucasus Pipeline, also known as the BTE (Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum) pipeline, the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline and Trans-Adriatic Pipeline. The ability of the Southern Corridor to counter, or at least check, Russia’s gas dominance by sourcing from eastern suppliers has been demonstrated as a viable concept with the construction of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline system (see map 2). The Trans-Anatolian and Trans-Adriatic pipelines, which would complete the link from the BTE gas pipeline to Europe, are at the planning stage.

The expected completion of these pipelines is 2017-2018, when they will begin moving gas exports from Shah Deniz II, meeting expected production times of the gas field. Figures have been advanced out to 2026, with flow expectation reaching as high as 60BCM. Furthermore, the pipeline route being demonstrated could serve as the basis for gas exports to Europe beyond Azerbaijani gas. These include gas from Turkmen and Kazakh producers through the possible Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) below the Caspian Sea. However, as no concrete plans have been agreed upon and developing major international gas pipelines takes years of planning before a single pipe is welded, it is not possible at this time to discuss the TCP with any certainty.

Another development that could check Russian gas export dominance is the proposed Nabucco pipeline. Nabucco would connect to Caspian production as well as gas volumes arriving through the TCP, were it to be realized. In addition, Nabucco touts an additional option of connecting to gas fields in Iran. Iran is the world’s second-largest gas reserve holder and its role in global gas has been largely overlooked due to diplomatic problems (see Iran for an in-depth discussion of Iranian energy and the diplomatic situation).

The mass of potential pipeline projects in the Southern Corridor, in addition to LNG developments underway in Qatar may indeed seriously undermine Russia’s gas dominance, and improve Iran’s prospects to tap into the Southern Corridor’s supply potential. The entire concept, however, is still largely theoretical. Western sanctions currently inhibit Iran’s export options. Additionally, gas produced in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan has no chance of reaching the Southern Corridor transit system without the construction of the TCP and the two pipelines linking Kazakhstan to Baku.

Were these developments to go ahead, the viability of the Southern Corridor and hence the Nabucco supply route would increase enormously, with Russia’s control of the gas market reduced in commensurate measure. It remains to be seen, however, if the major investment necessary to realize the project will be forthcoming. Meanwhile, Turkey’s need to satisfy its rapidly growing domestic consumption will weigh on any expectations of re-export/transit capacity.

Electricity

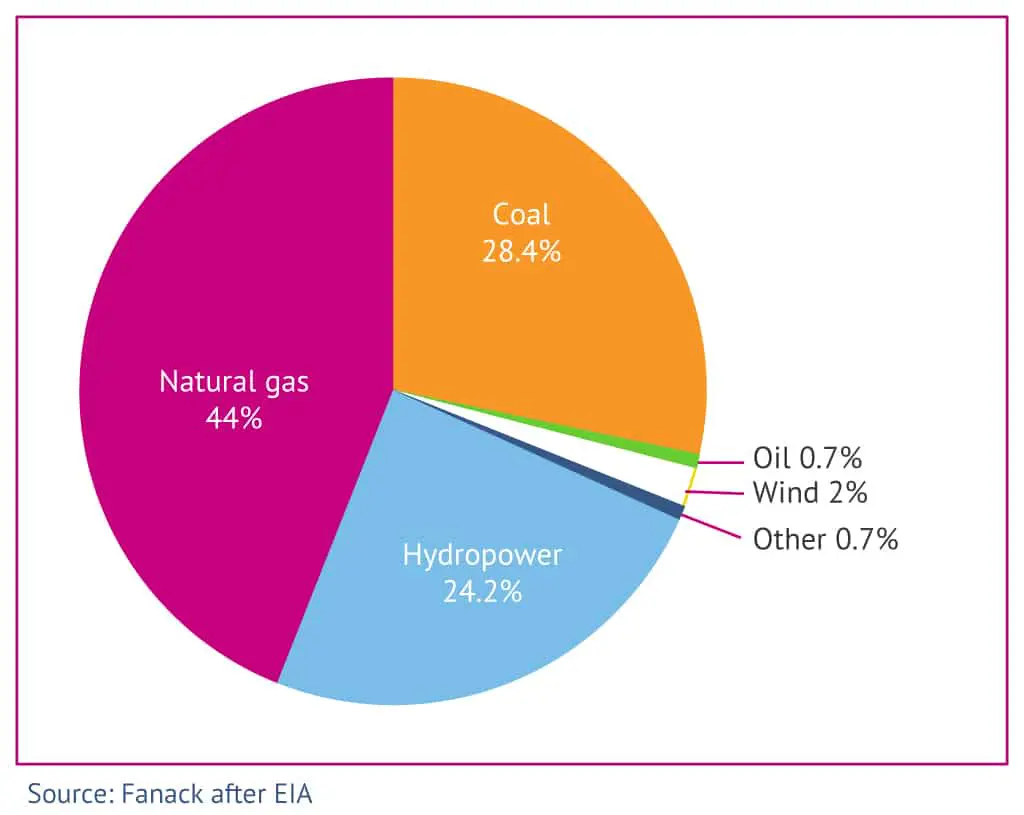

Fossil fuel and hydroelectricity generation accounts for nearly all of Turkey’s electricity generation capacity (56.1 million kilowatts in 2012), with natural gas as the most important source.

Turkey is a small producer of coal but also imports coal to supply the electric power sector – imports were 23% of total coal supply in 2012. As of 2008, total recoverable coal reserves were 2.36 billion metric tons, of which only 529 million metric tons, or about 23%, was “hard coal” (anthracite and bituminous). The remainder, 1.83 billion metric tons, consists of lignite coal reserves. Production in 2011 was 75.4 million metric tons. Only a small fraction of that production – less than 6% – is bituminous. Turkey has several lignite mines, but only one bituminous mine. Turkey imported about 27 million metric tons in 2010, and likely a similar figure in 2011 in order to satisfy 2011 consumption of 104 million metric tons.

In early 2013, Platts reported that “interest in developing coal-fired plants in Turkey has increased dramatically recently”. This followed statements by Energy Minister Taner Yildiz that Turkey has to diversify away from using imported gas to generate power and to make more of its underused domestic coal reserves, ostensibly in an effort to boost its role as a gas transit state.

Hydroelectric has also grown in importance, with investment in the sector. The country has, by government estimate, about 1% of the world’s hydroelectric potential in its waterways. There are several large rivers, including the Tigris and Euphrates that eventually flow in to Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Turkey’s viable hydroelectric capacity potential is estimated at 35,000 megawatts (MW). The installed capacity is currently about 23 gigawatts (GW), according to the International Hydropower Association.

Turkey signed an agreement with Russia in 2010 to build Turkey’s first nuclear power plant in Akkuyu, on the Mediterranean coast. The plant would have four units with a total capacity of 4.2GW and begin operating around 2020. Russian investors, namely Rosatom, agreed to finance a large proportion of the project. However, several Turkish ministries still need to approve the project before formal construction begins.