Under pressure from all sides, the triumvirate in 1914 decided to enter the empire into World War I, siding with its German ally (and Austria/Hungary). This decision was taken without notifying the Sultan, the Grand Vizier, or the Parliament. The defeat of Germany led to the fall of the empire in 1918.

The Ottoman rulers did not formulate a political answer to the aspirations of the oppressed, predominantly Christian peoples within the empire seeking freedom and equality. Instead, they opted for violence in a bid to stifle the growing opposition. This, in turn, offered the intrusive Western powers an opportunity to meddle in Turkish affairs. As a consequence, the Serbs, Bosnians, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Romanians managed to wrest themselves from Turkish rule in the course of the 19th century.

In its wake, the Ottoman Empire lost around 60 percent of its territory. In addition, following the Balkan Wars in 1912-1913, the empire lost most of its remaining territory in Europe. Nearly one million refugees, Muslims, left their homes as a result of the war. Fears arose among the Ottoman rulers that the end of their empire was at hand.

The triumvirate accordingly decided to engineer the expulsion of Christian peoples from its territory politically. In the same political vein, non-Turkish Muslim peoples – Kurds, Bulgarians, Bosnians, and Arabs – were forcibly assimilated into Turks. The result was creating an ethnic-religious homogenous Anatolia, which was deemed more equipped to withstand the (Christian) enemy.

The first to be targeted as a result of these politics were the Greeks in Western Anatolia. Fleeing the violence of state-organized armed bands such as Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), large numbers were subsequently deported to Greece over land or sea.

The around two million Armenians living in eastern Anatolia and the large cities in Western Anatolia could not be deported. The most obvious course of action would have been deportation to neighboring (Christian) Tsarist Russia. However, this country was allied to the empire’s Western enemies.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

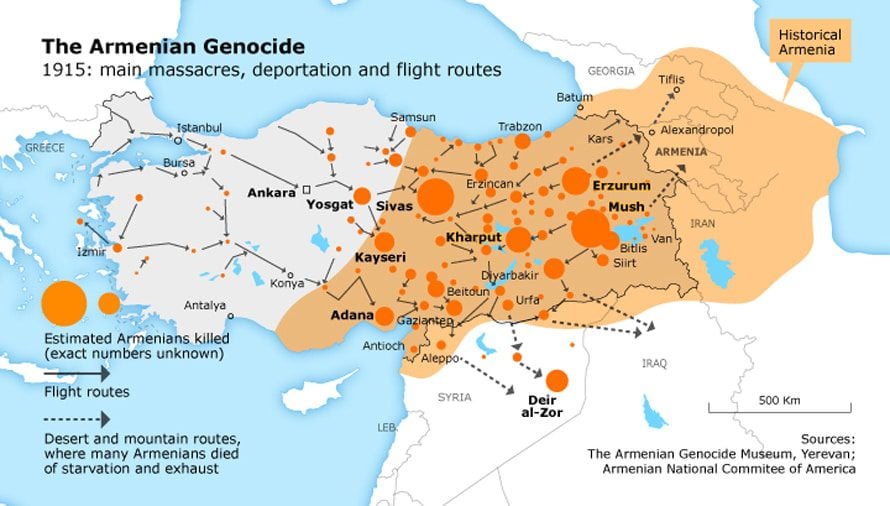

As a consequence, in 1915 the order went out to deport the Armenians to the south, to Syria and Mesopotamia. More was at stake than a ‘straightforward’ politics of deportation, as is evident from the widespread killings of representatives of the Armenian intelligentsia in the cities of Western Anatolia on the eve of the deportation, leaving the Armenian population bereft of its leaders.

The deportation went hand in hand with large-scale violence perpetrated by the abovementioned Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, but also soldiers, (state) police officers, and neighboring (Muslim) Circassians and Kurds, some of whom were members of the so-called Hamidiye regiments.

As a result, thousands of Armenians were slaughtered on the spot, women raped, young girls abducted, and their possessions looted. However, most of the victims died from the hardships on the long march from Anatolia to Syria and Mesopotamia (if they were not killed along the way). At least one million Armenians are estimated to have died.

Successive Turkish governments have always denied that there existed a politics of genocide in 1915 (and the following years). The same applies to the AKP, which has been in rule since 2002. Based on Article 305 of the 2006 Constitution, it is punishable by law to use the term ‘genocide’ in describing the events of 1915. According to the official reading, the deportation policy was not directed towards the extermination of the Armenian population.

However, research conducted by Armenian, Turkish, and other scholars, based on eyewitness reports of Armenians and other ethnicities, supplemented with archival research, has since offered sufficient evidence that the official Turkish reading of the 1915 events does not tally with the facts and that a politics of genocide did indeed exist.