Introduction

The concept of human rights has become a well-known and widely accepted term to use. Varying interpretations are possible, with differences usually being based on cultural background. Nonetheless, most of these understandings consciously or subconsciously include the basic rights outlined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The United Nations General Assembly (GA) adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on December 10th, 1948. It was written in the aftermath of World War II, “… as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind…” Thus it was truly meant to be universal, to protect citizens from any type of violation the world had recently experienced, as outlined in the Preamble and 30 Articles.

As such, it includes articles on the right to life in dignity; liberty and security; freedom of movement; right to nationality and education; just treatment of human beings and respect; as well as freedom of expressions and opinions, from torture or inhumane treatment, as well as economic, social and cultural rights.

International Human Rights Law

The Declaration is not legally binding, but is the basis of international human rights law. Two binding UN covenants were formed as a result of the UDHR; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Combined, these three documents are often referred to as the “International Bill of Human Rights”.

Over the years other conventions have been written to expand on and add to this fundament, focusing on a variety of topics such as refugees (1951 and 1967), discrimination of women (‘CEDAW’, 1979) and disabled persons (2008), against torture (1987), protection of migrant workers (1990), and against racial discrimination (1969) to name a few.

Additionally, the International Labour Organization has compiled a large number of conventions specifically related to work force and labour standards, of which 8 are considered ‘fundamental conventions’ and relate to freedom of association (1948, C087), collective bargaining (1949, C098), forced labour (1930, C029 and 1957, C105), minimum age (1973, C138), child labour (1999, C182), equal remuneration (1951, C100), equal opportunity and treatment (C111).

Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions are a revision of previously constructed conventions, adjusted after WWII and specifically focus on treatment of persons in time of war. It consists of four Conventions, and three additional protocols. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) explains that the Conventions “aims at ensuring that, even in the midst of hostilities, the dignity of the human person, universally acknowledged in principle, shall be respected.”

During a series of expert meetings, congregations by Red Cross agencies, and a confluence of government representatives over time, the articles were revised until a draft was represented at The Diplomatic Conference for the Establishment of International Conventions for the Protection of Victims of War in 1949. The Final Act was signed by fifty-nine nations, some of which no longer exist, and has attained more signatories since.

The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (CDHRI) was compiled by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in 1990, during the 19th Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers in Cairo, and has 57 signatories. This Declaration holds similar – if not identical – principles as the UDHR, but notably also included articles related to ‘jus in bello’ – acceptable wartime conduct, alike the Geneva Conventions. The CDHRI also addresses equality between women and men, rights of the child, freedom, right to medical care, right to self-determination, amongst others. Most notably is that this 25 Article document clearly lists the Sharia as reference point including for punishment. The CDHRI has been adopted by 45 countries, out of the total 57 members of the OIC.

Conventions Signed By Egypt

Egypt signed the Geneva Conventions on 10 November 1952, and the Additional Protocol I (Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts) and Additional Protocol II (Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts) on 9 October 1992. Moreover, it became signatory to the Convention for the Rights of the Child (CRC) on 6 July 1990, and signed the Optional Protocol to the CRC on June 2, 2007.

Egypt voted in favor of the UDHR, along with 48 other states, and has been a member of the OIC since 1969. The 8 fundamental conventions of the ILO have all been ratified by Egypt.

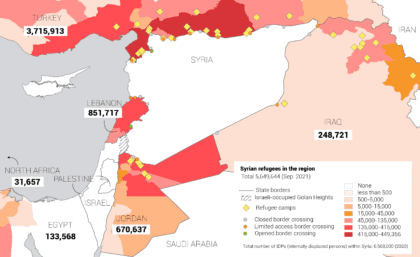

Refugees

The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees is based on Article 14 of the UDHR, and recognizes the right of asylum and protection of refugees. It was approved during the General Assembly meeting of December 14, 1950 and came into force on April 22, 1954. However, the original Convention limited its scope to refugees fleeing prior to 1 January 1951. As such, an additional protocol was compiled in 1967, removing these limitations.

On 22 May, 1981 Egypt acceded the Convention and Protocol. Through “accession” a state accepts the offer or the opportunity to become a party to a treaty, which has already negotiated and signed by other states. It has the same legal effect as ratification. Egypt did have reservations, expressed on 24 September 1981 against Article 12 (1), on the personal status of refugees; Article 20, on rationing; 22, allowing refugee children to attend public education; Article 23, concerning public relief; and 24, regarding labour legislation and social security. Reason for the reservations were that article 12 (1) was contradictory to Egyptian law, and the other articles consider refugees as equal. Upon submitting the reservation, it was explained that this was done to “avoid any obstacle which might affect the discretionary authority of Egypt in granting privileges to refugees on a case-by-case basis.”

Women

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women – also called CEDAW, was approved during the General Assembly Session on 18 December, 1979 and entered into force on 3 September 1981. Egypt signed CEDAW on 16 July 1980, and ratified it on 18 September 1981. Countries that have ratified or acceded CEDAW are legally bound to put its provisions into practice, and thereby agree to submit national reports on measures taken to comply with its obligations. Such reports are to be compiled at least every four years.

Egypt listed a number of reservations; against Article 9 (2), concerning children’s nationality – to avoid the child’s obtaining dual nationality; Article 16, Article 16, eliminating discrimination in marriage and family matters and child marriage – to ensure respect for provisions of Sharia; and Article 29 (2), discussing dispute between states concerning interpretation or application of the Convention – stating it is willing to comply with paragraph 1 of the same Article as long as it is not counter to Sharia. It is noteworthy that paragraph (2) specifically allows for reservation of paragraph (1).

Persons with Disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was approved during the General Assembly session on December 13, 2006 and came into force on May 3, 2008. Simultaneously, the Optional Protocol was approved, giving the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) competence to examine individual complaints with regard to alleged violations by States parties to the Protocol. The CRPD is the body of independent experts that monitors implementation of the Convention.

Egypt signed the Convention on April 4, 2007 and ratified it on April 14, 2008. It is not party to the Optional Protocol. The government made a reservation regarding Article 12, paragraph 2, recognizing persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others before the law; under Egyptian law such persons have the ability to acquire rights and assume legal responsibility but not the capacity to perform.

Torture

The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, also referred to as just the Convention against Torture, was adopted during the General Assembly session on December 10, 1984. On June 26, 1987 it was registered and thereby came into force. Its implementation is monitored by the Committee Against Torture (CAT), composed of ten individuals of various nationalities. All signatory states are obliged to send regular reports to the CAT, based on which recommendations are made. Egypt acceded to the Convention on June 25, 1986 with no reservations.

Migrant Workers

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families was approved by the General Assembly on December 18, 1990 and entered into force on July 1, 2003. Egypt acceded to the Convention on 19 February 1993, meaning prior to it entering into force and adding to reaching the threshold of 20 signatories needed for this to happen. It did submit two reservations, however, regarding Article 4, defining the term ‘members of the family’; and Article 18 paragraph 6, relating to reversal of convictions of the migrant worker or his/her family and its consequences. The nature of the reservations are not expanded on.

Racial Discrimination

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was approved by the General Assembly and accordingly opened for signature on March 7, 1966. It entered into force on January 4, 1969. Despite the obvious as stated in the Convention title, it aims to obliterate hate speech and promote understanding. Implementation of the articles is monitored by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, to which bi-annual reports are submitted by each signatory. It also is responsible for handling inter-state and individual complaints related to non-conformity to the provisions of the Convention, as prescribed in Article 14.

Egypt signed the Convention on September 28, 1966 and ratified it on May 1, 1967. In its reservation, where Egypt referred to itself as the United Arab Republic, was made against Article 22, pertaining to inter-state dispute resulting from interpretation or implementation of the Convention, stating that all parties to the dispute are to expressly consent to intervention of the International Court of Justice.

Human Rights in Egypt

The provisions of international treaties are incorporated into national legislation. However, a major obstacle to human rights was the state of emergency, which was in force continuously since 1981 until 31 May 2012, and allowed for arbitrary arrests, detention without trial, and restrictions on the freedom of assembly.

In reality, this meant that individuals could be detained indefinitely, as the limits of duration were circumvented and judicial rulings ignored, and individuals could be re-arrested immediately after their release.

Information about the number of detainees is not released by the authorities, and even less is known about specific charges, who is awaiting trial, and who is being detained without trial. Human-rights organizations estimate that more than 15,000 people may be locked up through administrative detention without trial.

Under domestic and international pressure, Mubarak called for the establishment of a National Council for Human Rights in 2003. The council was headed by former United Nations Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and had a mandate to receive complaints and monitor implementation of international agreements. The council was criticized by many local activists, who argued that it was merely a facade to deflect international pressure.

Recently, as part of the new regime’s policy to take over state institutions to consolidate its rule, President Morsi has reorganized the National Council for Human Rights. It is now headed by the religiously devout supreme-court judge Husam al-Ghiryani; of the 27 members at least seven are Islamists, including Muslim Brothers and Salafis. Only two members are well known human-rights activists. Three of the members are Christians, two of whom are women; the council has three female members.

Political Freedom

Freedom House, the international NGO for freedom and democracy, gave Egypt a low score for political freedom before the revolution of 25 January: on a scale of zero to seven, Egypt received 1.3 for ‘free and fair electoral laws and elections’; 2.5 for ‘effective and accountable government’ and 1.8 for ‘freedom of association and assembly’. According to Freedom House, the government ‘routinely violates its citizens’ civil and political rights, including freedom of assembly and association, as well as the right to participate in the political process as a candidate or elector’.

The state had almost total control over the establishment and operation of opposition parties through the vetting authority of the Political Parties Committee.

The Egyptian Constitution recognizes the right of assembly, but authorities require advance notice of public rallies and protests, and permission is usually denied. In the past, if granted permits, protests were confined to a limited area and met with vast numbers of security personnel. Security forces frequently cracked down on protests, arrested participants and physically abused them on site and while in custody. In 2008, a ban was issued on demonstrations in places of worship.

The Egyptian Constitution affirms the country’s multiparty political system, but anyone posing a meaningful challenge, particularly to the President, faced harsh consequences. This is illustrated by the fate of Ayman Nour (born 1964) of the Tomorrow Party, who finished a distant second at the 2005 presidential elections. While campaigning, Nour was arrested on charges of forgery. He was subsequently released but detained again after the elections. He was tried and sentenced in 2005 to five years’ imprisonment.

Since the revolution, multiple parties have been established, most of which obtained licenses. While the state was previously preoccupied with preventing the development of Islamist parties, the Communist Party is still awaiting licensing, while many religiously based parties have already taken part in parliamentary elections.

Civil Liberties and Police Abuse

For ‘protection from state terror, unjustified imprisonment, and torture’, Egypt under Mubarak scored a low 1.1 points on the Freedom House scale. The security apparatus, including the secret police, combined with the Emergency Law (until 2012) and military courts, are responsible for the abuse of human rights. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International and many local human-rights organizations report on the routine use of torture, mistreatment of political prisoners and ordinary citizens, arbitrary detentions, and trials before military and state security courts. Estimates from 2010 vary from 5,000 to 10,000 people who were under long-term detention without charge or trial.

In the last years of Mubarak’s rule, many cases of police abuse were brought to light through the Internet. In response to national and international condemnation, some police officers faced prosecution and were disciplined. The Ministry of Interior claimed that the use of torture is not systematic.

Police Torture: Systematic, Incidental, or Arbitrary

While many human-rights organizations under Mubarak reported that police torture was being used systematically in Egypt, the Ministry of Interior countered that it happened only occasionally. More embarrassingly for the government, two high-ranking police officers published books in which they described the regular use of violence and intimidation in day-to-day police work. Abuse was used not only to extract information during interrogations or to force confessions but also simply ‘to show who is boss’, as one police officer put it. Anyone could be subject to abuse, not just obvious enemies of the state – terror suspects – but any suspect who did not show the desired respect.

During the revolution of 25 January, an estimated 846 people died, and more than 1,000 were wounded by police and security forces. Throughout 2011, the army too has been responsible for the violent treatment of demonstrators, the torture of activists, and the use of military detention and trials for civilians (in June 2012, conservative estimates put the number of cases at 8,000 or more).

Although the Emergency Law under which these practices took place has been lifted, the violent treatment of demonstrators does not appear to have changed since Morsi assumed the presidency. Recent demonstrations in support of the Syrian people were dispersed with tear gas and buckshot.

Discrimination

Homosexuality is not illegal in Egypt, but laws criminalizing debauchery are used to prosecute homosexuals. Crackdowns occur occasionally. In 2002, more than fifty men were arrested on a floating nightclub, the Queen Boat. The State Security Court convicted 23 to five years’ imprisonment. In 2008, several HIV-positive men were arrested, accused of debauchery, and taken to court; the case is still pending.

During the January 2011 protests, several gay Egyptian men reportedly joined the demonstrations but did not specifically demand gay rights. Since the revolution, many gay bars and hangouts have developed as a consequence of the preoccupation of the police and security forces with political activists. The recent Islamist assumption of power, however, does not augur well, as the Muslim Brotherhood and other organizations consider homosexuality ‘unnatural’ and ‘against God’s will’.

Human Rights After the Military Coup

Following the popularly backed military coup that ousted Mohamed Morsi, the first freely elected president of Egypt, on 3 July 2013, authorities quickly cracked down on all Islamic TV stations that backed the president, who belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood. The military accused those channels of inciting violence against protesters and the police.

The authorities also raided the offices of Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr, part of Al-Jazeera news network, which was criticized for its pro-Morsi coverage, took it off the air, and arrested several of its journalists, three of whom were later tried on terrorism charges.

After the televised speech by then defence minister and strongman Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi on 3 July, supporters of the deposed president staged two sit-ins, a large one at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square, in eastern Cairo, and a smaller one at al-Nahda Square, near Cairo University. Thousands of Muslim Brotherhood members and sympathizers took part in the sit-ins for nearly six weeks before security forces finally raided both camps and cleared them in 12 hours.

The death-toll claims vary greatly: the health ministry said that 600 people died and nearly 4,000 were injured, while the Muslim Brotherhood put the number of deaths at 2,600.

While most reports acknowledge that some of the protesters were armed, the vast majority were peaceful. With hundreds of bodies turning up in mosques bearing gunshot wounds and some charred beyond recognition, several human-rights organizations spoke out against the violent dispersal and killing of peaceful protesters, blaming security forces for not following international standards for the dispersal of protests and for failing to minimize bloodshed.

In early March 2014, the National Council for Human Rights (NCHR) released its report on the events, claiming that the first shot was fired by the protesters and that the use of firearms by the police was “justified”. But the report criticized the police for failing to exercise restraint and using disproportionate force.

Anti-Protest Law

The dispersal of the Muslim Brotherhood sit-ins set several events in motion. Subsequent protests and marches were met with live fire from security forces, and the interim president eventually passed a new protest law in November 2013 that requires protesters to seek permission from the Interior Ministry before any protests and bans overnight sit-ins. Activists and rights groups opposed the new law, worried that it would curtail the freedom of assembly and prohibit mass demonstrations, similar to the ones that toppled Mubarak and led to the overthrow of Morsi, while giving the police free rein to use force and arrest protesters.

Human Rights Watch published a statement saying that the new law “would effectively give the police carte blanche to ban protest in Egypt. The bill would ban all demonstrations near official buildings, give the police absolute discretion to ban any other protest, and allow officers to forcibly disperse overall peaceful protests if even a single protester throws a stone.”

The organization also stressed that the law “falls far short of Egypt’s obligation to respect freedom of assembly under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” The government and the interim president have, however, rejected all attempts to overturn the rule.

Banning Political Opponents

Following the dispersal of the Muslim Brotherhood sit-ins, the police cracked down on many of the group’s leaders and members, jailing thousands, including Mohamed Badie, the group’s highest authority, and Mohammed Khairat Saad el-Shater, its second in command.

The widespread crackdown on members of the group forced them to go underground. Many detainees reported bad detention conditions and torture at the hands of the police. A smuggled video from a high-security prison in Egypt, released by The Telegraph, showed tiny dirty cells shared by three prisoners in deplorable conditions.

Sarah Leah Whitson, the Middle East and North Africa director for Human Rights Watch, told Al Arabiya News that, “If these practices are part of a state policy and as systematic as initial reports suggest, they could amount to crimes against humanity.”

Following several terrorism attacks in various Egyptian cities, the Egyptian government moved on 25 December to officially declare the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization. While Islamist militant groups claimed responsibility for the attacks and the Muslim Brotherhood condemned them and insisted it was involved only in peaceful protests, the government blamed the group for the attacks.

This could lead to arrested members of the Islamist group being tried under severe terrorism laws. In March and April 2014, the judiciary in Egypt handed down sweeping death sentences in the cases of more than 1,200 detainees, among them Muslim Brotherhood leader Badie, for acts of terrorism and the killing of police officers, later commuting the sentences of 492 of them to life in prison.

This drew condemnation from most Western countries: in the United States, the White House released a statement that the two rulings “[defy] even the most basic standards of international justice,” urging the Egyptian government to “end the use of mass trials, reverse this and previous mass sentences, and ensure that every citizen is afforded due process.”

The Islamist Muslim Brotherhood was not the only group to face pressure from the government. A court ruling on 28 April 2014 banned the activist group April 6 Youth Movement, one of the groups most involved in the protests that overthrew Mubarak in 2011. The movement’s co-founder, Ahmed Maher, and two other young secular protesters were sentenced to three years in prison for challenging Egypt’s protest law.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Human Rights’ and ‘Egypt’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: