Bayt al-Suhaymi stands as a symbol of Cairo's rich architectural heritage, offering a glimpse into Egypt's cultural tapestry during the Ottoman era.

Youssef M. Sharqawi

Bayt al-Suhaymi (House of Suhaymi) is the only integrated residence embodying the architectural style of Cairo and Egypt during the Ottoman era.

Its historical significance spans four centuries, serving as a prominent cultural hub for hosting various heritage and cultural events.

History and Location

Beit al-Suhaymi is situated in the al-Gamaliya district, one of the oldest districts in Old Cairo. It is located on the al-Darb al-Asfar alley, which connects the al-Mu’izz Lidin Allah al-Fatimi Street and al-Gamaliya Street. The house is adjacent to the Khanaqah of Baybars al-Jashnakir.

While some credit the creation of this landmark to Prince Qitas Bey in 1630 AD, historical research and archaeological findings suggest that it was constructed in two stages. The southern section of the house was built by Sheikh Abdulwahab al-Tablawi in 1648, while the northern section was built by Haji Ismail Çelebi in 1796. Çelebi is said to have merged the two sections into a unified dwelling.

Bayt al-Suhaymi acquired its name from Sheikh Amin al-Suhaymi, who served as the sheikh at the Turkish riwaq (a venue for learning and acquiring knowledge) at the al-Azhar Mosque and was the building’s last occupant. The house remained in its original state until the al-Suhaymi family left it in 1931.

In that year, the Egyptian government’s Committee for the Preservation of Arab Antiquities approached the family, proposing to register the house and its contents as Islamic antiquities in exchange for significant financial compensation. At the time, the family was offered compensation amounting to 6,000 Egyptian pounds, equivalent to approximately 55.5 million US dollars today.

A Look Inside

Influenced by Ottoman architecture, Bayt al-Suhaymi was designed with separate spaces for men and women. The ground floor, known as the selamlik, was exclusively reserved for men, while the upper floor, known as haremlik, was reserved for women. Consequently, the ground floor did not include any additional rooms or halls, serving solely as a reception area for male visitors.

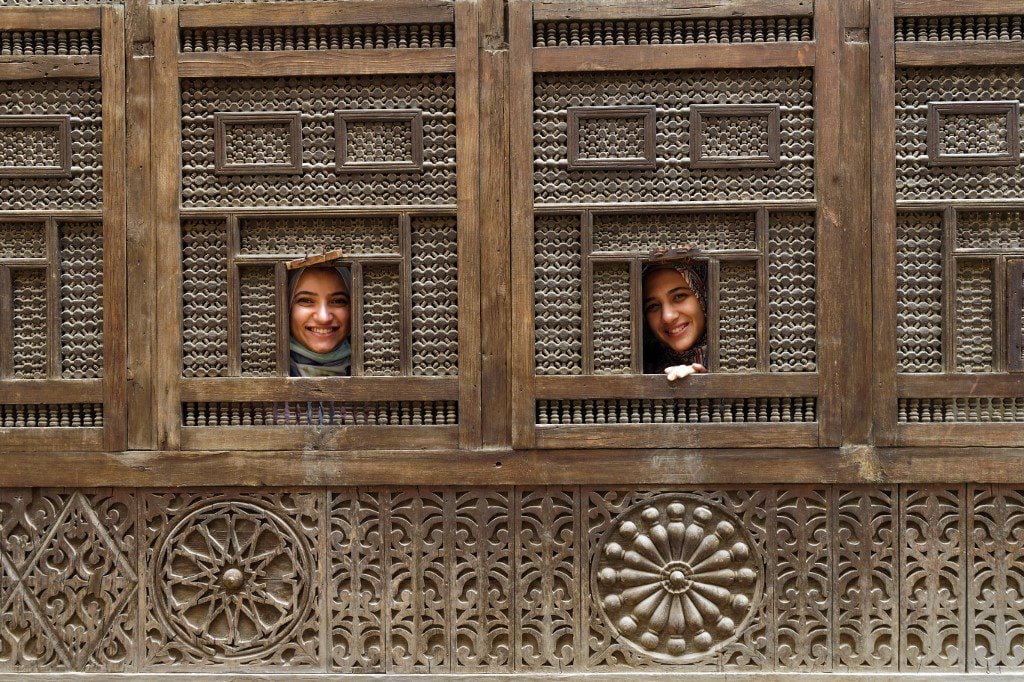

As detailed on the website of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, Bayt al-Suhaymi epitomises the residential architectural style prevalent during the Middle Ages. The exterior facade features high windows, while the upper mashrabiyas are adorned with turned wood.

Upon entering the house, visitors are greeted by a distinctive feature known as the “broken corridor,” a hallmark of Islamic architecture. This corridor – also referred to as the “al-Majaz” – serves to maintain the privacy of the household’s occupants.

The al-Majaz extends to the courtyard or sahn, a central feature of the residence adorned with beds full of plants and trees. The sahn, akin to other Islamic houses, serves as a focal point, with rooms opening onto it rather than directly to the outside.

This design not only preserves the privacy of the dwelling but also provides protection against wind and dust.

Sheikh Tablawi Section

Within the Sheikh Tablawi section lies a large hall, designed like many chambers within the house. The hall is characterised by two iwans, enclosing a relatively lower central space known in Islamic architecture as Dargah. The floor of the hall is decorated with coloured marble, contributing to its aesthetic appeal.

Adorning the walls are excerpts from the renowned poem ‘al-Burda’ by Imam al-Busiri, which he devoted to praising the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The ceiling of the hall, akin to others in the house, is decorated with wooden panels and beams embellished with intricate floral and geometric patterns.

This hall served as a selamlik, where the head of the household would receive his male guests and offer them food. Luxurious mattresses were arranged within the two iwans for guests to sit on, while a large copper tray, placed on a stand, was used for serving food.

Positioned at the apex of the hall is the lounge, a distinctive feature characteristic of Islamic house architecture. The lounge functions as a summer room for male gatherings, resembling the hall but with an open facade facing north to capture a refreshing breeze during summer evenings.

It also overlooks the sahn, providing a serene view of the garden. Like the rest of the hall, the ceiling of the lounge is embellished with complex floral and geometric designs.

Ismail Çelebi Section

The Ismail Çelebi section encompasses a selamlik akin to the one found in the Tablawi section.

However, what sets apart the Ismail Çelebi Hall is its larger size and enhanced architectural and decorative intricacies. Adorning the ceiling of the hall are floral and geometric motifs, culminating in a small dome known as the shukhshikha, which features small openings facilitating the ingress of air and light.

The presence of this dome, coupled with the mashrabiya opening into the house’s sahn, ensures a continuous circulation of fresh air within the hall, maintaining a pleasant and mildly humid atmosphere throughout the day.

Adjacent to this hall lies another hall designated for the recitation of the Koran, customary in the architecture of grand Islamic residences and palaces. A prominent feature within this space is a large chair adorned with intricately turned wood, typically reserved for the sheikh reciting the Koran.

Another notable element within the room is a sizable copper chandelier, providing the only source of light, which was lit using wicks dipped in oil.

Renovation

In the early 1990s, Bayt al-Suhaymi underwent extensive renovation due to its deteriorating condition, as some 14,000 cracks were present within the structure in 1993. The renovation was facilitated by a grant of ten million Egyptian pounds from the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development.

The project encompassed the documentation, renovation and development of the Bayt al-Suhaymi area, spanning from 1996 to 2000.

Upon completing the renovation, a decision was made to repurpose Bayt al-Suhaymi into a centre for artistic creativity under the auspices of the Cultural Development Fund of the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

By the early 2000s, the house emerged as a hub of cultural and artistic vitality within the al-Gamaliya district, welcoming folklore groups and hosting art exhibitions within its halls.

According to the Ministry of Culture, the Fund facilitated the hosting of prominent Egyptian folklore musical groups at Bayt al-Suhaymi, with one notable ensemble being the Nile Ensemble for Music and Folk Singing. Led by renowned theatre director Abdulrahman al-Shafi’i, this ensemble comprised over 55 artists.

Moreover, the al-Suhaymi Creativity Center recently showcased another form of folk art, namely the art of puppetry or karagoz and shadow play. Workshops were held to teach young individuals the fundamentals of this art, aimed at nurturing a new generation capable of continuing this cultural legacy.

Al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah Epic

Bayt al-Suhaymi used to host “Ramadan nights,” during which it was customary to recount the epic tale known as the al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah.

This tale stands as one of the most celebrated stories within Arab heritage, firmly entrenched in the intangible cultural heritage that continues to captivate the Arab imagination to this day.

The al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah unfolds as a sprawling saga, covering a historical journey that encompasses the migration of the Bani Hilal tribe, their displacement and exodus from their homeland in Upper Najd to Tunisia. The epic comprises approximately one million verses of poetry.

The al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah holds profound cultural significance in Upper Egypt, cherished by its people who sing its verses. In this region, residents commit thousands of verses from this epic to memory, often convening for nightly gatherings by the Nile River or amidst agricultural fields.

During these gatherings, individuals recite verses from the epic, captivating audiences, particularly the elderly who have memorised many of its verses. This epic holds profound significance within Egyptian culture, representing a cherished aspect of intangible heritage.

Notably, the verses of the epic were not written down but rather passed down orally through generations.

The popular al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah is structured into four primary parts, each containing a series of sub-stories. The initial part, known as the Mawaleed (Births), starts before the birth of Abu Zaid al-Hilali, the epic’s main protagonist, as well as other notable figures, including Hassan, Diyab and Bedeir.

This part chronicles the events leading up to the emergence of the main protagonist and culminates with his recognition and appointment as a knight.

The second part, known as the Riyadah (Pioneering), follows Abu Zaid and his nephews Yahya, Yunus and Mar’i, as they embark on a journey towards Tunisia, a passage to the Maghreb. In some interpretations, Tunisia symbolises the entirety of North Africa. Throughout their journey, Abu Zaid and his companions traverse various countries and encounter numerous tribes along the way.

The third part, named Taghriba (westward journey), unfolds as a narrative of an extensive and intricate journey involving the tribes of Hilal, Jaafar, Duraid, Riyah and Zaghba. This journey starts in Najd and ends upon reaching Tunisia.

The fourth and final part, titled al-Aytam (orphans), depicts the demise of the main protagonists, followed by the emergence of a new generation of protagonists. This concluding episode is structured akin to the preceding parts of the epic, beginning with the orphans’ births and progressing through multiple journeys.

It is significant to highlight that the epic’s rendition in Upper Egypt diverges from its northern counterpart in various aspects, including dialect, literary techniques (both poetic and prose styles), musical instruments, costumes and methods of reception.

Al-Abnudi and al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah

Following Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war, the esteemed poet Abdulrahman al-Abnudi dedicated nearly three decades of his life to meticulously researching the al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah as recounted by Arab singers and storytellers.

His primary objective was to document this epic and transcribe it from oral tradition to recorded and written form, thereby safeguarding it from the threat of extinction.

Al-Abnudi’s journey took him across regions, including Sudan, Algeria and Libya, as well as the borders of Chad and Niger, before reaching Tunisia. The culmination of his efforts resulted in the publication of the epic in five volumes.

Al-Abnudi furthered his efforts to preserve the heritage epic by presenting furthered his efforts to preserve the heritage epic by presenting it on Egyptian radio. He recorded multiple tapes in his own voice, narrating the epic.

Subsequently, in 2010, he embarked on a new phase of his endeavour, recording ninety episodes in a studio, in which he narrated the epic in its entirety. The Egyptian television news sector produced these episodes to compile them into a comprehensive document of this cherished heritage.

Al-Abnudi likely spent extensive periods listening to the epic at Bayt al-Suhaymi, which may have influenced his decision to record and document it there.

Bayt al-Suhaymi and al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah

The al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah became strongly associated with Bayt al-Suhaymi through the Cultural Development Fund programme for over a decade.

Each year, during the nights of Ramadan, the epic was presented at the house in various sessions featuring different storytellers, one of whom was renowned storyteller al-Sayed al-Dawy, known as the “Sheikh of storytellers.”

It is noteworthy that the Abdulrahman al-Abnudi Museum of the al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah was inaugurated in 2015, but al-Abnudi passed away mere days before its opening. The museum houses a comprehensive collection, including the complete volumes of the al-Sirah al-Hilaliyyah, along with an extensive array of cassette tapes containing narrations of the epic. Additionally, the museum boasts a collection comprising 15 volumes, 96 cassette tapes and a selection of CDs.