Introduction

The First Crusade began in 1095 when pope Urban II called for a military expedition to the Byzantine Empire to help it fight the Seljuk (Turk) assailants and to take control of the Holy Land, which at that time was under the rule of the Egyptian Fatimid.

This inaugurated a period of two centuries in which Christians and Muslims often fought one another – and sometimes their own co-religionists – across the region between Anatolia and Palestine and in Egypt. At times they did however also cooperate.

The first troubles arose when the Norman Bohemond finally took the city of Antioch, one of the patriarchal sees of Christianity, from the Seljuk. The crusaders had promised the Byzantine emperor to hand back to him the territories they conquered, but Bohemond did not comply.

Shortly after his conquest, however, an army led by Kerbogha of Mosul retook the city. Eventually, the crusaders managed to reconquer Antioch, but then internal strife broke out. Some stayed, some went on to conquer Palestine, the Holy Land.

Godfrey of Bouillon’s army went south. In the beginning, the Fatimid did not seem overtly distressed by the crusaders’ passing through their territory and even considered helping them against the Seljuk. This changed, however, when the Europeans approached Palestine – and Egypt. In 1099, Godfrey of Bouillon conquered Jerusalem.

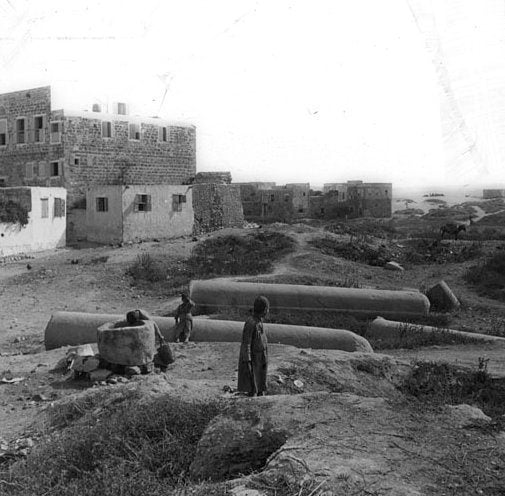

However, the Lebanese and Syrian territories proved more difficult to conquer – and even less easy to hold. The cities of Tyre (Sur), Sidon (Saida), Beirut, and Tripoli (Tarabulus al-Sharq) changed hands a few times, and although already fortresses before the crusades, were now strongly fortified.

Toward the end of the 12th century, the European rulers – the Franks, as they were called, although not all of them came from France, the Frankish kingdom – claimed to be the masters of the Lebanese mountains.

Shifting alliances

However, the situation remained complicated. There were still Muslim princes who remained masters of their fiefs in the mountains. Secondly, the newcomers accommodated the established communities in several ways. There were shifting alliances, with former enemies fighting alongside or transforming into opponents. Some territories – like those of the Bohtor, Sarahmour, Tirdalan, and Aramoun families, near Beirut – fell under both the Christian bishops and the legendary Saladin, who fought the Christians in the name of the jihad – following in that respect Nur al-Din, Saladin’s predecessor.

Saladin, who won decisive battles – such as the Battle of Hattin in 1187 that led to the fall of Jerusalem and the end of the occupation of that region by the Franks – was famed not only for his strategic acumen but also for his courageous and chivalrous feats as a warrior. His reputation was in that respect similar to that of his adversary Richard Lionheart, and witnesses have reported that both men respected, or even liked, one another.

Neither the Christians nor the Muslims always closed ranks. When the Franks undertook to conquer the Lebanese cities, they were sometimes stopped by Maronites. These later supported the crusaders but ceased to do so toward the end of the 13th century, which also meant the end of the crusader era. At one point, the French count Raymond III of Tripoli was Saladin’s ally against Baldwin, King of Jerusalem – before switching sides.

Afterward, Raymond was defeated by Saladin. In the Muslim world, there was a patent hostility between Shiite Egypt and Sunnite Baghdad. The emirates located between the two powers – fearing the Turkish Seljuk – remained divided in their allegiance. Eventually, in 1292, it was the Mamluks, a new Egyptian dynasty – though of Turkish origin and Sunnite – who brought the final blow to the crusaders. By then, the eastern part of their territory had been invaded by the Mongols, who came as far as Damascus.

The Crusades (eight in total) cost many lives and brought a lot of destruction, disease, and disorder. But on the whole, the local inhabitants were allowed to remain true to their faith – except for slaves and prisoners of war. They also retained their local authorities and justice system.

In many ways, the eastern and western cultures influenced one another. Trade thrived, especially in the coastal regions. Traders – whether they were Muslims, Christians, or Jews – enjoyed special protection when crossing borders, even when they had to enter ‘enemy’ territory. Caravans traveled across the whole region, ships went from Egypt to Tyre to Constantinople and further.

After the last of the crusaders left the Lebanese coast, many Christian traders also left and settled in Cyprus. After a few years, however, their ships returned to the Lebanese ports.