Introduction

The Arabic- and French-language newspaper Hadikat al-Akhbar signified the emergence of the modern mass media in Lebanon when it launched in 1858. Lebanon’s early newspapers reflected the interests of the country’s Ottoman rulers, and the 1865 Press Law consolidated government control over the media. Some journalists fled to Egypt, while others published illegal pamphlets and publications in the capital Beirut in growing opposition to the Ottoman leadership.

In 1924, Lebanon’s French rulers enshrined their capacity to shut down opposition newspapers and introduced a scheme to ‘reward‘ loyal journalists. Yet the printed press continued to grow, and by 1929 there were over 270 Lebanese newspapers, and increasing calls for national sovereignty. In 1938, the French established Lebanon’s first broadcast radio station, which continued to air after independence.

Lebanon’s initial post-independence press and radio environment was tightly controlled by the government but television was an exception, emerging as a private, rather than state-owned, enterprise. The first television station was founded by La Compagnie Libanaise de Télévision in 1959, although the government retained the right to censor content.

The 1962 Press Law increased journalists’ rights through the creation of a press syndicate and an editors’ syndicate, however it also constrained freedom of expression through the assertion that ‘nothing may be published that endangers national security… national unity… or that insults high-ranking Lebanese officials… or a foreign head of state’.

The Lebanese civil war (1975-1991) saw media outlets targeted but hundreds of publications survived the ordeal, while many unlicensed television and radio stations had begun broadcasting during the conflict.

In an effort to restore order, the government amended the press law in 1994, with further restrictive measures allowing for journalists to be detained or fined prior to a court conviction. It also issued the 1994 Audio Visual Law, which made Lebanon the first Middle Eastern country with a regulatory framework allowing for both private radio and television broadcasting.

Lebanon’s major television broadcasters moved into satellite broadcasting relatively late in 1996, by which time Lebanese audiences had been exposed to worldwide satellite content for several years. The country’s media outlets were quicker to adopt internet technology, available in Lebanon since 1994, with three Lebanese dailies publishing online in 1996 and approximately 200 online news websites by 2002.

Lebanon’s 21st-century media is burgeoning, with private newspapers, radio stations, television channels and online publications. However, the environment is highly partisan and reflective of the country’s political and sectarian divisions.

In fact, the Lebanese media’s most distinctive feature is that all major outlets are affiliated with a particular sect or political movement. The environment has also become more volatile in recent years, as Lebanon suffers the violent overspill from Syria’s ongoing civil war, while also serving as a regional and international hub to cover the conflict.

Freedom of Expression

Lebanon’s media environment is one of the most open in the Middle East, although still repressive by global standards, and ranks 98th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders 2016 World Press Freedom Index.

Article 13 of the Lebanese Constitution, last amended in 2004, asserts that ‘the freedom of opinion, expression through speech and writing, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly and the freedom of association, are all guaranteed within the scope of the law’.

The ‘scope of the law‘ includes repressive measures outlined in the country’s penal code, military justice code and existing press and audio visual legislation. Article 384 of the penal code stipulates punishments of up to two years’ imprisonment for insulting ‘the president, the flag or the national emblem’, while Article 317 criminalizes the publication of content that incites ‘sectarian or racist strife’.

It remains an offence to insult a foreign head of state, and broadcast media are forbidden from airing content that could damage the nation’s economy, depicts unsanctioned political or religious gatherings or promotes relations with Israel.

Individuals and outlets who are deemed to have contravened Lebanese media laws can either be tried in the special publications court or a military tribunal. In 2014, the special publications court ruled against journalists in 37 of 40 cases, mostly involving allegations of defamation against high-profile Lebanese officials.

Self-censorship is common due to the dual pressures of an intensely partisan media environment and the government’s confusing and contradictory legislation. Furthermore, the Lebanese censorship bureau, officially termed the Media and Theatre Department, can sensor any foreign publication, television show or movie prior to distribution. Recent examples include the banning of The Da Vinci Code, as it was considered anti-Christian, and The West Wing, as it was considered anti-Arab.

Although physical attacks on media figures are relatively rare compared to other countries in the region, Lebanese journalists are still subject to intimidation. In August 2015, at least eight journalists were physically assaulted by security forces when covering anti-government protests in Beirut amid the city’s escalating waste-disposal problem.

In February 2017, the offices of independent TV channel al-Jadeed were attacked by a 300-strong crowd armed with fireworks, firebombs and rocks, in a politically-motivated attack. Lebanon’s media landscape has also become increasingly violent and volatile in light of the ongoing civil war in neighbouring Syria.

In 2014, Danish journalist Jeppe Nybroe and Lebanese-Palestinian journalist Rami Aysha were abducted from a Lebanese border town after attempting to report on journalist kidnappings in Syria. Both were released a month later.

The Lebanese security forces employ the Cyber Crimes Unit to monitor and sometimes detain bloggers and online journalists. As with the print and broadcast media, defamation laws are often enforced by the Lebanese government to curb dissent. In October 2015, journalist Mohammed Nazzal was tried in absentia and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for criticizing the Lebanese judiciary on Facebook. In May 2016, Nabil al-Halabi, a lawyer and human rights activist, was arrested for Facebook posts criticizing government officials. He was released three days later after signing a ‘document of submission‘.

Television

Cable and satellite television is pervasive in Lebanon, and the majority of the population has access to foreign channels through official or pirated subscriptions. However, local channels catering to specific sects and political interests continue to attract the highest viewership. A 2009 Nielsen survey placed no foreign news channel among the top ten preferred channels. The most popular local outlets are as follows:

Lebanese Broadcasting Company (LBC) – Founded during the Lebanese civil war in 1985 by The Lebanese Forces, a Christian-nationalist militia, and emerged to become the country’s most successful wartime channel. In the 1990s, the channel came under substantial domestic pressure because it criticized the ongoing Syrian military presence in the country. In 1996, it formed its internationally orientated satellite channel LBC-Sat, based in the Cayman Islands and therefore not subject to Lebanese broadcasting law, allowing it to broadcast previously censored films and television programmes. Saudi financiers, including media mogul Prince al-Waleed Bin Talal, own nearly half of LBC-Sat, and their sizeable investments have allowed the satellite network to grow and compete internationally. LBC is one of the region’s best-known entertainment channels, having piloted a series of highly popular variety and game shows over the past decade. In 1996, it formed its internationally orientated satellite channel LBC-Sat, based in the Cayman Islands and therefore not subject to Lebanese broadcasting law, allowing it to broadcast previously censored films and television programmes.

| Channel | Percentage of respondents who identify channel as a favourite |

| Lebanese Broadcasting Company (LBC) | 62% |

| Al-Jadeed | 54% |

| Orange TV (OTV) | 39% |

| Future TV | 27% |

| Murr TV | 26% |

| Al-Manar TV | 25% |

Table 1. Most popular local television channels by percentage of viewership. Source: Dubai Press Club, Arab Media Outlook Survey 2009-2013 (2010).

Al-Jadeed – Established as an independent channel by the Lebanese Communist Party in 1991 under the name New TV, and has since changed hands several times. In 1992, it was purchased by Tahsin Khayyat, a Qatar-affiliated Sunni businessman and rival to Rafiq Hariri. Throughout the 1990s, the channel broadcast illegally and was shut down in 1996. It was finally granted a license in 2000. In 2001, it was rebranded al-Jadeed and claimed to operate as a ‘neutral‘ Lebanese news outlet. However, the channel’s offices have been attacked in recent years, firstly by unknown gunmen in 2012, after a talk show guest extensively criticized the Amal movement and Hezbollah, and secondly by hundreds of protestors in 2017, after a programme was aired that insinuated the Amal movement’s leader, Nabih Berri, was withholding information about the disappearance of the movement’s founder.

Orange TV (OTV) – Granted a license in 2006 and officially began broadcasting in 2007. It is privately owned and affiliated with the Lebanese president, Christian Maronite Michel Aoun, and his Free Patriotic Movement (FPM).

Future TV – Owned by the prominent Hariri family and is the primary channel targeting Lebanon’s Sunni Muslim community. It was established by Rafiq Hariri in 1993, and in 2007, a sister channel, Future News also began broadcasting. In 2008, both channels were temporarily forced off air after Shiite Hezbollah militias seized its Beirut offices. A 2010 Ipsos survey estimates that both channels attract 5.7 per cent of primetime audiences.

MTV – Established in 1991 and owned by the Greek Orthodox Christian al-Murr family. The channel was shut down in 2002, following a raid by security forces, in a move that Ghazi Aridi, then minister of information, condemned as “purely political”. The channel relaunched in 2009, after significant changes in Lebanon’s political environment, including the withdrawal of Syrian troops.

Al-Manar TV – Privately owned satellite television channel established in 1991, although unlicensed until 1998. The channel is closely affiliated with Hezbollah. The channel broadcasts 24 hours a day and uses international newswire footage and reporting in much of its programming. However, it also airs its own talk shows and news bulletins. In 2006, the channel’s Beirut offices came under heavy aerial bombardment from Israeli aircraft during the Israeli offensive in Lebanon.

Al-Mayadeen – Pan-Arab satellite station established in Beirut in 2012. Details of its ownership and funding sources remain scarce, with the channel simply claiming to be financed by ‘Arab businessmen‘. The station is openly supportive of Hezbollah, the al-Assad government in Syria and Iran. The channel was established as an alternative to the Gulf-owned, pan-Arab networks al-Jazeera and al-Arabiya, and many of al-Mayadeen’s initial staff were former al-Jazeera journalists who had objected to its coverage of the 2011 Syrian uprising.

Radio

Lebanon has dozens of private radio stations, and radio broadcasting maintains wide listenership. However, only a select few stations have ‘class A‘ licenses, which allow them to air political and news content. Like television channels, the majority of Lebanese radio stations are affiliated with a particular sect or political party. The most popular stations that broadcast news or political content are as follows:

Sawt El Ghad – Founded in 1997 and affiliated with the FPM. The station mainly broadcasts local and international news but also airs Arabic music and entertainment programming.

Sawt Lubnan – Established in 1975 as the country’s first commercial radio station but with a strong focus on news programming. It has a longstanding affiliation with the Lebanese Phalanges Party, and in recent years the station has been subject to a legal ownership dispute between the party’s current leadership and the heirs to the station’s post-war director. Since 2011, Sawt Lubnan has been split into two stations of the same name, each representing one side of the dispute.

| Station | Percentage of total audience exposed to the outlet at least once per day |

| Sawt El Ghad | 19% |

| Sawt Lubnan | 17% |

| Sawt Lubnan al-Hurr | 15% |

| Sawt al-Mada | 10% |

| Radio Orient | 9% |

Table 3. Most popular social media platforms in 2015. Source: Northwestern University Qatar Survey, Media Use in the Middle East, 2016.

Sawt Lubnan al-Hurr – Launched in 1978 and affiliated with the Lebanese Forces party, focusing on political programming and news broadcasts.

Sawt al-Mada – Established by the FPM in 2009.

Radio Orient – Affiliated with the Future Movement and founded in 1995. The station airs both entertainment and informational broadcasting as well as political and sports talk shows. It airs news bulletins in Arabic, French and English.

Ithaat al-Nour – Founded in 1988 as a pro-Hezbollah station broadcasting from Beirut. Like al-Manar TV, the station came under attack from Israeli aircraft in 2006.

Radio Liban – The country’s only public radio station, established by French officials as Radio Orient in 1938.

Press

Lebanon has one of the highest ratios of private newspaper ownership in the Middle East, and therefore one of the most diverse print environments. However, accurate circulation statistics are difficult to obtain. A 2009 Ipsos survey revealed the most popular newspapers to be the following:

Annahar – Founded in 1933 with a historical moderate-right, anti-Syria stance. The newspaper is supportive of the March 14 Alliance, a coalition of anti-Syria political parties led by Saad Hariri. In 2005, Gebran Tueni, the editor-in-chief and grandson of the newspaper’s founder, was assassinated along with Samir Kassir, one of the newspaper’s most prominent columnists. The newspaper launched its online version Naharnet in 2000, publishing in Arabic and English, which has since gone on to become one of the country’s most popular websites.

Al-Balad – Tabloid-style newspaper launched in 2003 with a sensationalist tone and a focus on social and cultural issues as well as politics. Since 2010, it has also published a French-language edition.

Al-Mustaqbal – Launched in 1995 by the Hariri family, al-Mustaqbal has strong connections with the Future Movement and its leader Saad Hariri.

Al-Akhbar – Originally founded in 1938, but relaunched in 2006 as a liberal, critical publication. The newspaper quickly developed a reputation for covering previously taboo subjects and has championed LGBT rights and feminist causes, while also openly supporting Hezbollah. The latter support allows the newspaper unprecedented access to various political scoops.

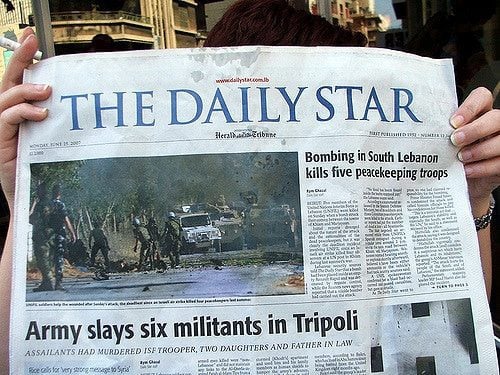

The Daily Star – Established in 1952 as an English-language newspaper that expanded to become a pan-Arab publication by the 1960s. Its editor-in-chief, Kamel Mroue, was assassinated in 1966, causing the newspaper to temporarily cease publication. Nowadays, it is owned by Saad Hariri and is the only Lebanon-based, English-language daily, although its print edition has suffered financial difficulties.

L’Orient-Le Jour – Founded in 1970, L’Orient-Le Jour is a prominent French-language newspaper. The publication has traditionally taken an anti-Syria stance, and was temporarily closed down in 1976 during the Syrian occupation of Beirut.

Social media is very popular in Lebanon. However, the BBC remarks that internet speeds are ‘notoriously slow‘, meaning that simple messaging apps are the most widely used.

Social media platforms have increasingly been used as a means of collective activism and campaigning in the country. In 2015, in protest against the government’s inadequate waste-disposal policy in Beirut, the citizen-led ‘YouStink‘ campaign went viral across a number of platforms.

By February 2017, YouStink’s official Facebook page has gained over 220,000 followers, and the protest movement has grown to address a number of issues pertaining to corruption and incompetence among Lebanon’s political elite.

However, the government has displayed limited tolerance towards the movement: 14 civilians were tried in a military court in January 2017 for their part in the 2015 YouStink protests held in Martyr’s Square.

| Platform | Percentage of respondents who use it |

| 98% | |

| 82% | |

| YouTube | 67% |

| Facebook Messenger | 46% |

| Viber | 46% |

| 22% | |

| Google Chat/Hangouts | 22% |

| 17% |

Table 3. Most popular social media platforms in 2015. Source: Northwestern University Qatar Survey, Media Use in the Middle East, 2016.

Online Publications

Freedom House estimates that 50 websites were blocked in Lebanon in 2015, the majority of which were Israeli sites or contained content relating to pornography, prostitution or gambling. Online news websites are generally permitted to operate without censorship, although the government occasionally issues content removal requests, typically citing defamation law.

The most popular online publications include Tayyar.org, affiliated to the FPM and publishing local cultural and social stories in addition to more traditional news coverage. NOW News, formerly known as Now Lebanon, was established as an online news platform in the wake of Rafiq Hariri’s assassination and is affiliated with the Future Movement and March 14 Alliance. As of March 2017, Now News’ website states the portal is ‘temporarily off-air‘. Lebanese-Forces.com is also popular and serves as a news outlet with an overt bias towards the Lebanese Forces party.

Some popular online publications display a less overt political affiliation, including Elnashra.com and LebanonFiles.com. Both primarily operate as news wire services, often relaying stories from other sources, while Elnashra.com also provides an internet radio broadcast.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Lebanon’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media