Introduction

It would be impossible to write about popular Lebanese music without mentioning Fairuz, the singer who has been called the ‘soul of Lebanon’ and her country’s ‘ambassador to the stars’. She and her collaborators, composers Assi Rahbani and Mansour Rahbani, rose to prominence at a time when Lebanon was finding its national identity, following the end of French rule in 1946.

Fairuz was born in 1935 as Nouhad Haddad. She began her singing career as a teenager, performing in the chorus at the Lebanese radio station. It was there that she met and began working with the Rahbani brothers. She would later marry Assi, the eldest brother.

Many intellectuals and artists have left Lebanon over the centuries. Each period of violence, each wave of repression by the then occupying power, each (civil) war was followed by a wave of emigration.

Hence, the Lebanese arts developed not only in Lebanon itself – where Beirut is probably the most important cultural centre – but also in the countries where émigrés found a second home. Damascus and Cairo and, further away, Paris, London, New York, and Rio de Janeiro are thus also minor Lebanese cultural centres, especially for Lebanese literature and cinema.

In present day Lebanese literature, but also in Lebanese music, film or fine arts, the Civil War (1975-1990) and its aftermath are recurrent themes. Many artists want to remember and document these events and their aftermath, or to fight against the political and religious divisions that led to the war.

Moreover, years of violence and destruction left the Lebanese people with a deep hunger for beauty, creativity and artistic ways of expression. From the 1990s, Lebanon has witnessed a wave of artistic expression, but also the founding of various festivals such as the Salon du Livre, the Beirut International Film Festival, or al-Bustan (music) Festival

Literature

Lebanon has many publishing houses, which publish in Arabic, French and English. In 2009, UNESCO designated Beirut as World Book Capital, ‘in particular thanks to its efforts for cultural diversity, dialogue and tolerance as well as for the variety and dynamism of its programme’.

Each year (with a few exceptions), Beirut hosts the Salon Francophone du Livre, the largest literary salon outside of Paris and Montreal. It also hosts an Arab and International Book Fair (representing 170 publishers and attracting 35,000 visitors). Lebanese literature is also published in countries with large numbers of Lebanese emigrants. Poetry plays an important part in Lebanese literature. Prominent musicians have written music to traditional poems, and newspapers deem poetry important.

The Nahda: a New Cultural Movement and the Shaping of Lebanese Literature

The first signs of a new cultural movement became apparent in 1957 with the foundation of Shir, a magazine for experimental poetry established by the Syrian poet Adunis (the alias of Ali Ahmad Said Asbar) and others. Poets from all over the Arab world settled in Beirut, attracted by the free press and the relatively tolerant intellectual atmosphere that reigned at the time.

In the same period, modern narrative prose began to take shape. Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad, Maroun Abboud and Yusuf Habashi al-Ashqar published their first novels and short story collections, heavily influenced by European and Russian naturalism.

Others, such as Suhayl Idris, were drawn to the existentialist movement of Jean-Paul Sartre and his group. In the second half of the 20th century, female writers began to gain ground. In 1968, Layla Baalbakki published her autobiographical feminist novel Ana ahya (‘I live’), which made her famous not only in Lebanon but across the Arab world.

The Arab defeat in the 1967 conflict with Israel and the subsequent civil war (1975-1990) in Lebanon deeply affected Lebanese society, including the cultural and literary scene. The war featured in everything that was written, be it the political novels of Suhayl Idris, the prophetic novels of Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad or the surrealistic stories of the political activist and writer Elias Khoury.

Among female writers, the war seemed to function as a catalyst and a source of inspiration. New names rose to prominence, notably Emily Nasrallah, Hanan al-Shaykh and Hoda Barakat, who would soon become known as the ‘Decentrists of Beirut’. The Decentrists tried to demystify Lebanese society by identifying the controversies underlying the political crisis. According to them, politics was not the only issue at stake and they advocated a reconsideration of traditional, pre-war patriarchal values.

In the early 1980s, a new genre of literary prose emerged. The war was still present but was stripped of the heavy ideology that had previously dominated the written word. Writers such as Hasan Daoud, Rashid al-Daif, Alawiya Subh and Iman Humaydan concentrated on the daily life of the Lebanese people during the war.

The new millennium saw the emergence of a new generation of writers who were still children when the war broke out. In their literary work, they try to recover the youth that the war stole from them. Rabee Jaber is one of the most prominent representatives of this generation.

In the past 20 years, Beirut has grown into a thriving cultural and literary centre. Each year (with a few exceptions), Beirut hosts the Salon Francophone du Livre, the largest literary salon outside of Paris and Montreal, and the Beirut Arab Book Fair (representing 170 publishers). In 2009, UNESCO designated Beirut as World Book Capital, ‘in particular thanks to its efforts for cultural diversity, dialogue and tolerance as well as for the variety and dynamism of its programme’.

Modern Lebanese Authors and Notable Works

Salah Stétié (1928), writer, poet and diplomat, writes in French and has published more than 35 books, including poetry, biographies of other poets (Mallarmé, Rimbaud) and essays, such as Culture et violence en Méditerranée. He also translated Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet into French.

He was awarded the Grand prix de la Francophonie in 1995. A selection of his poems was translated into English under the title Cold Water Shielded. His works have also been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Turkish and Serbian. In 2006, he received Serbia’s Smederevo Award, the oldest poetry award in Europe. In 1996, the Arabic-language l iterary journal al-Adab published a special issue about him. He is also the subject of three documentary films.

Adunis (born 1930) is a poet, philosopher and literary critic. He founded two literary journals, Majallat Shir (‘poetry’) and Mawaqif (‘positions’). He has been named several times as a possible Nobel laureate. The first collection of Adunis’ verse in English, The Blood of Adonis, appeared in 1971 and was reissued in 1982 as Transformations of the Lover.

Gibran Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) is one of the most important writers of Lebanese origin. From the age of 12, he was raised in Boston, United States. He studied art in Paris for two years, then returned to the United States, where he live from 1912 in New York.

His name was shortened to Khalil Gibran by mistake upon his arrival in the United States, and he is known under this name outside Lebanon. Gibran’s early works were written in Arabic, but from 1918 he published mostly in English. Among his best known works is The Prophet, a book of 26 poetic essays, which has been translated into more than 20 languages.

Vénus Khoury-Ghata (born 1937) writes in French and has lived in France since 1973. A well-known and highly regarded poet, novelist and short story writer, she was awarded the Prix Mallarmé in 1987 for Monologue du mort, the Prix Apollinaire in 1980 for Les ombres et leurs cris, and the Grand Prix de la Société des gens de lettres for Fables pour un people d’argile in 1992.

Her most recent collection of poems, Quelle est la nuit parmi les nuits, was published in 2004. Her work has been translated into Arabic, Dutch, German, Italian and Russian. She was named a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 2000. Her most recent novel, Sept pierres pour la femme adultère (2007), was shortlisted for two important prizes.

Elias Khoury (born 1948), novelist, playwright, literary critic and sociologist, is considered one of the leading contemporary Arabic intellectuals and writers. In his youth, he enlisted in the Fatah movement within the Palestine Liberation Organization, then fought in Lebanon’s civil war. His novels have been translated into many languages. For several years, he was the editor of al-Mulhaq, the weekly literary supplement of the daily newspaper al-Nahar. Among his best known books are Little Mountain, The Journey of Little Gandhi, The Kingdom of Strangers and Gate of the Sun. He lives in Beirut and New York.

Amin Maalouf (born 1949) lives in Paris and writes in French. A versatile author of novels, essays and even opera librettos, he is a compelling storyteller. Much of his work seems aimed at creating more understanding among (opposing) groups. Many of his novels are set against a historical backdrop and some of his characters are historical figures.

His most important novels include Leo the African, The Rock of Tanios, which was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1993, and Balthasar’s Odyssey. Origins, translated into numerous languages, traces his grandfather’s history within the wider context of Lebanon’s and the world’s history.

Jabbour Douaihy (born 1949) is an academic, novelist and journalist. His works include Ayn Ward, June Rain, which was shortlisted for the 2008 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, also known as the ‘Arabic Booker Prize’, and Autumn Equinox.

Alexandre Najjar (born 1967), who lives in France and writes in French, is one of the most important writers of his generation. He was awarded the Grand prix de la Francophonie in December 2009. His books include a biography of Khalil Gibran, The School of War, Berlin 36, Phoenicia and Le roman de Beyrouth, about the tragic events in 1860 and thereafter.

Film, Theatre, and Television

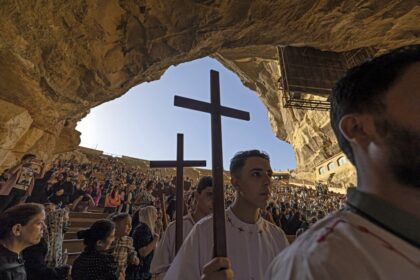

Theatre is a recent art form in Lebanon. The only traditional theatre – imported from Iran – is that of the Shia Muslims, who perform a ritual kind of theatre that enacts the passion of Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, in which tears are shed for the fate of Hussein and his family (ahl al-bayt). Hussein – the Twelfth Imam, revered by the Lebanese Shia – was slain in the Battle of Karbala in 680, on Ashura (the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic year).

This theatre is also found in Damascus. Around 1910, it was translated into Arabic. Since 1930, the Battle of Karbala has been enacted every year in Nabatiya southern Lebanon, on Ashura.With the rise of Hezbollah, this kind of theatre became more and more important. Today, similar plays are staged in other towns and villages in the region and have been opened to spectators from other regions and other religions. Professional actors and directors have tended to replace the former amateurs, certainly in Nabatiya.

Western-style theatre was first introduced in the 19th century, when a rich merchant, Marun al-Naqqash, commissioned a performance of Molière’s play L’Avare (‘the miser’), which was entirely sung. For a long time, this was the dominant form of theatre and several artists still mix music, song and performance. Ziad Rahbani, for example, now mainly known as a singer-songwriter, started out as a comedian.

One of the foremost playwrights and directors is Elie Karam. Born in a Muslim part of Beirut to Christian parents, he fled the civil war to Austria and Canada, where he studied dramatic arts. After the war he returned to Beirut, where he wrote and directed several critically acclaimed plays exposing controversial issues in the Middle East. His latest production, Tell Me About the War and I Will Love You, won several prestigious prizes and was staged at the renowned Avignon Theatre Festival in France in 2010.

Cinema is a popular art form in Lebanon. For such a small country, Lebanon has produced many film directors. Ziyad Doueiri, Ghassan Salhab, Nigol Bezjian and Samir Habchi are among the best known. Maroun Bagdadi, Bourhan Alaouie, Rafiq and Heini Surur are seen as the forerunners of contemporary Lebanese ‘art cinema’. Many film directors spent the civil war abroad, where most of them learned their trade. The civil war and its aftermath are very present in their films, although the directors – perhaps because they spent a long time outside the country – mostly do not identify themselves with one party. They prefer to describe what war does to people.

The younger generation of film directors (Randa Chahal Sabbag, Nadine Labaki, Youssef Fares, Assad Fouladkar, Danielle Arbid, Philippe Aractingi, Khalil Joreige) tend to focus on different themes, often relating to the difficulties of daily life.

Music

Following the Second World War (1945-1949), Beirut established itself as the cultural capital of the Middle East, with the Lebanese music scene leading the way. Lebanese music has a distinct sound due to the country’s unique fusion of Western and Eastern influences.

Even Lebanese folk compositions often reference Western contemporary music. This rich cultural mix has also influenced Lebanese dance, and from the 1970s Lebanese dancers began blending the traditional dabke with Western classical and modern dances such as ballet, hip-hop and breakdance.

During the civil war, the tradition of musical fusion continued. The alternative Western music scene was also popular and continued to be so after the war. This went hand-in-hand with a growing interest in Arabic pop, and an Arabic music industry emerged that was focused in and on Beirut. In the same period, an extensive underground music scene developed, covering blues to jazz, hip-hop to rock, metal to post-punk and psychedelic to electronic-core. In the 21st century, experimental music took hold and today, a new wave of Lebanese indie rock youth music has emerged.

Pioneers of music education

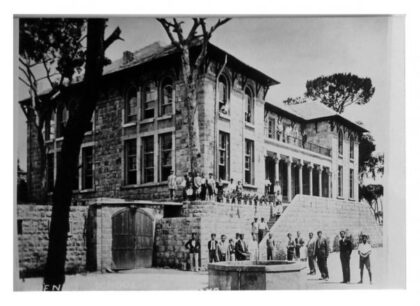

Since the creation of modern Lebanon in 1920, music has been a feature of all aspects of private and public life. Wadih Sabra, composer of the Lebanese national anthem, founded the Music School in 1910. It became the Lebanese National Conservatory in 1929, the first of its kind in the Middle East. By the middle of the 20th century, the conservatory was an autonomous institute supported by the state under the supervision of the minister of education.

From 1953 until the start of the civil war in 1975, the conservatory was a regional cultural hub, served as a national archive and music research centre, and had its own chamber orchestra directed by Raif Abillama.

During the war, it was all but destroyed as instruments, documents, archives and libraries were looted or burned. It resumed its role as a national music school, archive and research centre in 1991. In 1995, it was upgraded to a national institute for higher education and was renamed the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music. Since its inception, the conservatory has had two programmes: Western classical and Oriental classical. Modern Oriental and jazz were added later.

universities have also incorporated music into their curricula. The first university to establish a music department in the Middle East was Université Saint-Esprit de Kaslik (USEK) in 1970. Other Lebanese universities followed suit, especially after the civil war.

The new millennium brought more private initiatives to create modern music schools, which subsequently opened in the major cities of Beirut, Jounieh, Byblos, Tripoli, Zahle, Tyre and Sidon. The best established is the Mozart Chahine School of Music, which has three locations and offers a musical diploma.

Traditional music

Zajal

The Ottoman Empire, of which Lebanon was a part for several centuries until the empire’s collapse in the early 20th century, greatly influenced Lebanese culture, and these influences were fused with the previously accumulated cultural heritage of the region. This resulted in a musical tradition that shares similarities with neighbouring Syria and Palestine but is also quite distinct.

One of the oldest Lebanese music forms is today considered a living tradition, especially in rural areas. Called zajal, it is partly or totally improvised sung poetry. In most cases, it takes the form of a competition between two poets/singers or two teams, who declaim or sing verses in a colloquial dialect. The main melodies are produced by the poets themselves and supported by percussion instruments such as the daf, rikk and tabla.

Occasionally, traditional instruments such as the nay, oud or kanoun will provide the accompaniment. Zajal parties are stand-alone night entertainment, where the two teams sit at opposite tables and sing while drinking arak (an alcoholic spirit) and/or eating meze (appetizers). The poets/singers (known as zajjalin) are usually respected social figures recognized for their talent and are invited to perform at weddings and special celebrations.

The zajjalin improvise or sing the poetic discourse in verses, and the last few words are repeated as a unified chorus by most of the people present.

Although very much alive in Lebanon, zajal is not exclusive to the country and is still practised, if only rarely, in parts of Palestine and coastal Syria. Among famous contemporary Lebanese zajjalin are Chahrour al-Wadi and Rachid Nakhle, who wrote the lyrics for the national anthem, Zein Sheib, Talih Hamdan, Zaghloul al-Damour, Hanna Moussa, Anis al-Feghali, Moussa Zgheib, Asaad Said, Sayed Mohammad Mustafa, Khalil Rukoz, Victor Mirza, Sharbil Kamel, Edward Hareb, Assaad Assaad and Mouzir Khairalla.

Dalouna and Howara

Unlike zajal, dalouna is a fully sung poetry form that is usually memorized although it can be improvised as well.

Dalouna can be adapted to any occasion, whether it is happy (weddings, births), sad (funerals), nationalistic (victory, independence), social (end of a day’s work in the field, village anniversary, holiday) or even religious. It is very much alive in Palestine and Syria as well, and is similar to Jordanian and Iraqi dabke. Although modern Lebanese Arabic pop music only borrowed elements of zajal, known as moual, it has fully embraced dalouna, and modern versions of dalouna have been sung by contemporary Arabic pop artists such as Assi al-Hillani, Faris Karam and Najwa Karam.

Howara is a purely Lebanese music form adapted from zajal. However, whereas dalouna is common to most countries in the Levant, howara is specific to Lebanon. Dalouna is a traditional Levantine dancing music and howara is a Lebanese folk dancing music and, in most cases, there is no dalouna or howara without dabke.

Dabke

Dabke is the name of a folk dance of Phoenician and Canaanite origins. Today, dabke is as much a musical style as a dance style. It is still danced at weddings and even in nightclubs, and professional dabke groups can be found all over the country.

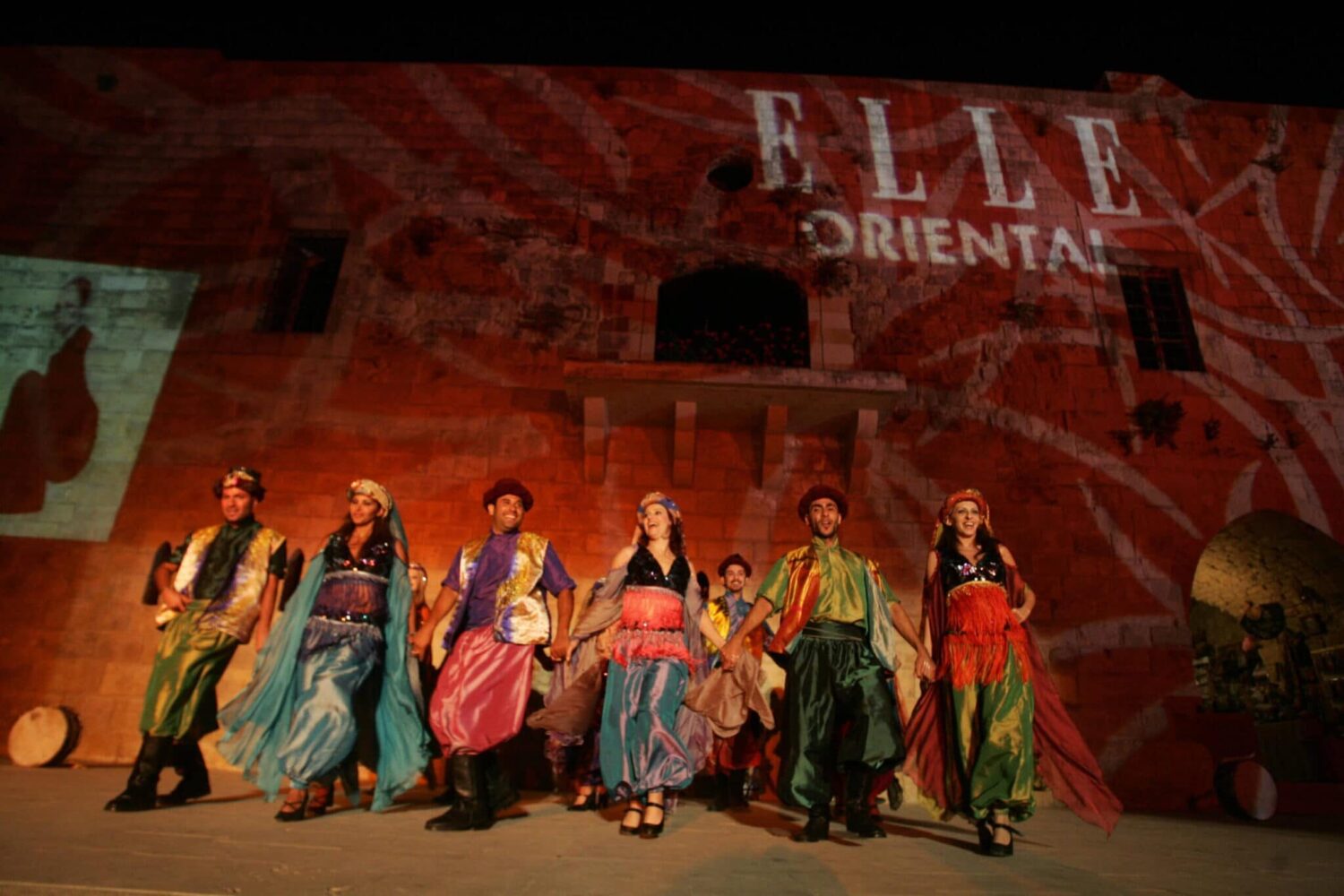

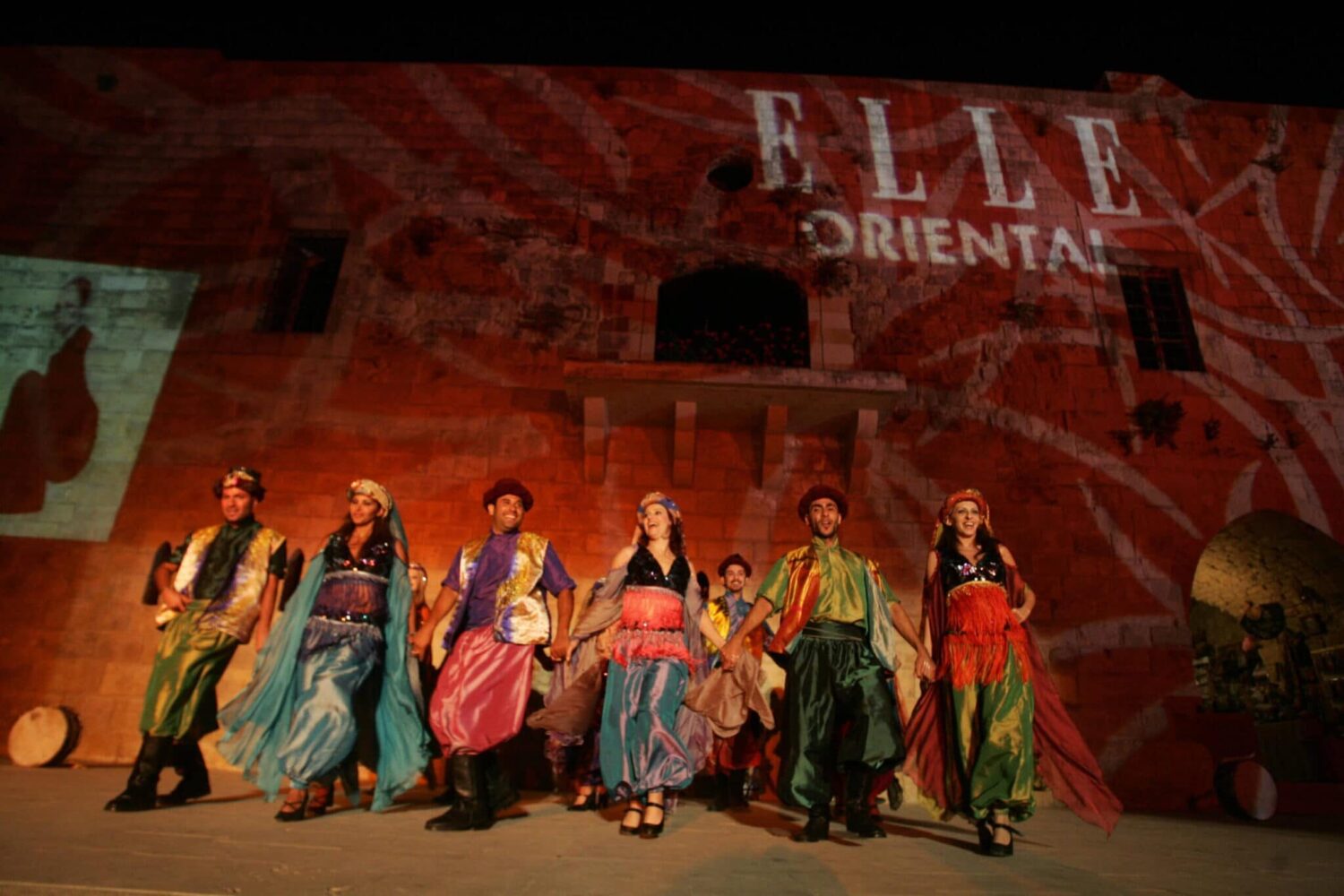

The best known of these is Caracalla, which was founded in 1970 and established a dance school for theatrical musical and dance-based plays. It is considered the pinnacle of the marriage between Western and Oriental artistic expression and produced a genre so unique it has become known as Caracalla style.

Tarab

The word tarab has no exact translation in English, although ‘ecstasy through the enjoyment of music’ or ‘being enchanted by the music’ come close. Tarab is also the name of a modern classical Arabic music genre.

Tarab is not originally a Levantine art form; it has a long history that can be traced back to the Golden Age of Arabic music during the Abbasid era. Tarab is nonetheless very popular in Lebanon, whether in its classical form, such as Mouwashat Andalusia and Qoudoud Halabiya (from Aleppo), or in the more contemporary interpretation that was popularized in the 1960s by the Egyptian singers Um Kulthum and Abd al-Wahab.

Although the majority of modern tarab singers are Egyptians, a few Lebanese artists, such as Wadih el-Safi, who is nicknamed ‘the immortal voice of Lebanon’, have successfully ventured into the genre. George Wassouf is another popular modern tarab artist in Lebanon despite being of Syrian origin.

The Rise and Rise of Lebanese Music

Modern Lebanese music is characterized by a fusion of Western and Arab influences, reflecting the complex and multicultural nature of Lebanese society.

Fairuz

It would be impossible to write about popular Lebanese music without mentioning Fairuz, the singer who has been called the ‘soul of Lebanon’ and her country’s ‘ambassador to the stars’. She and her collaborators, composers Assi Rahbani and Mansour Rahbani, rose to prominence at a time when Lebanon was finding its national identity, following the end of French rule in 1946.

Fairuz was born in 1935 as Nouhad Haddad. She began her singing career as a teenager, performing in the chorus at the Lebanese radio station. It was there that she met and began working with the Rahbani brothers. She would later marry Assi, the eldest brother.

The trio burst onto the national stage in 1952 with the song ‘Itab‘ (‘blame’), which became their first hit.

Ramzi Salti, a Lebanon-born Stanford University lecturer who runs the podcast Arabology, which showcases music from the Arab world, told Fanack that the songs the Rahbani brothers penned for Fairuz were a departure from the lengthy pieces punctuated by orchestral interludes performed by previous icons of Arab music such as Oum Kalthoum.

Fairuz’s songs were as short as Western pop songs, three or four minutes, and she favoured a clearer vocal tone over the traditional nasal singing style of Arab music.

Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers “revolutionized Lebanese music and they revolutionized Arabic music in general”, Salti said. “People initially rejected that and thought it was too Western, that it wasn’t Lebanese at all, that she was just copying the West, but it was groundbreaking.”

The rejection did not last long and Fairuz became a national icon. She appeared regularly at the Baalbeck International Festival, along with other famous singers of the day, including Sabah and Wadih el-Safi. The Rahbani brothers composed musical plays for the occasions, in which Fairuz played a starring role.

Fairuz did not flee the country after civil war broke out in 1975, but she refused to perform inside of Lebanon during the war, instead touring abroad.

Pop Divas

Nevertheless, Soapkills went on to become one of the most beloved acts in Lebanese independent music. After eight years, the duo split and went on to pursue successful solo careers – Yasmine in Paris and Zeid in Lebanon.

Other Musical Movements

The popularity of Soapkills precipitated a flourishing underground and independent music scene, encompassing a wide range of genres, from the jazz and bossa nova of Tania Saleh to the ensemble al-Rahel al-Kbir, or The Great Departed, which has penned satirical songs mocking the ideology of Islamic State.

Lebanon has also seen the rise of hip-hop, with artists including El Rass and Rayess Bek. Likewise, hip-hop groups have sprung up in the Palestinian camps in Lebanon and among young Syrian refugees living in the country.

There has also been an active Lebanese heavy metal scene since the 1990s, Blaakyum being the longest running group. The scene has periodically run into problems with Lebanese authorities, facing several waves of raids and arrests in search of ‘Satanic’ activities.

Arab Spring

Although Lebanon was not at the centre of the 2011 Arab Spring protests and uprisings, it was part of a wave of more rebellious musical voices coming out of the Middle East during that period.

In 2008, Zeid Hamdan recorded ‘General Suleiman‘, a reggae song directed at Michel Suleiman, then Lebanon’s president. The song’s lyrics included references to ‘militia men’, ‘warlords’ and ‘corrupt politicians’ and ended with a cry of ‘gene-gene-general, go home!’

After the release of a video for the song, Hamdan was briefly imprisoned in 2011 on charges of defaming the president. His arrest caused widespread outcry among fans. Hamdan maintained that the song was intended as a call for the president to be a force for peace, after clashes broke out between Hezbollah and rival groups in 2008.

Mashrou’ Leila

The Lebanese independent music scene has recently seen another break-out success with the rock group Mashrou’ Leila. The act, formed in 2008 by a group of students at the American University of Beirut, has found commercial success across the Middle East.

The group’s distinctive style is driven by singer Hamed Sinno’s emotive voice and the violin work of Haig Papazian. Sinno is openly gay, a rarity for a pop culture figure in the Arab world, and the band’s lyrics deal with issues of sexuality, substance abuse and political violence, topics that are taboo in much of the region. In April 2016, the group was banned from playing in Jordan, although the ban was later lifted.

The group released its fourth album, Ibn El Leil, in 2015. It debuted at number one on local iTunes channels, and reached number 11 on the international Billboard Charts, prompting the Guardian newspaper to write: ‘It’s such an impressive performance that stadiums seem not only possible but imminent.’

Architecture

Architecture is what mostly remains of Lebanon’s past. Byblos was the first city ever built entirely of stone and there are still traces of this very early architecture, going back thousands of years, and now mostly hidden under Roman ruins. Most of the architectural treasures have been damaged or even destroyed during one of the many wars that have been fought in this region over the centuries. In addition, several earthquakes have brought destruction.

Despite being in ruins, Baalbek, in the Beqaa Valley, is one of the most impressive Roman sites in the Middle East. The Great Jupiter Temple and the Great Bacchus Temple took well over a century to build, starting in 60 BCE.

Not far from these temples is also one of the two remaining Umayyad ruins, the Great Mosque, built partly with stones from the Roman temples in the 7th and 8th centuries. The other Umayyad building is in Anjar, also in the Beqaa Valley. What is left here of the Umayyad city dates back to the 8th century.

Crusader Architecture

The crusaders and those who fought them were also builders. The crusaders built churches and fortresses. One of these churches is the 12th-century St John the Baptist in Byblos, a Romanesque-style structure, although one of the portals is in typical 18th-century Arab style. Not far off is the Crusader Castle, built by the Franks in the 12th century.

In the northern city of Tripoli are the remains of the Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles (12th century). Two centuries later, the Great Mosque arose on the ruins of the crusader cathedral St Mary of the Tower. This is the oldest and largest Mamluk mosque in Lebanon. Next to it is Lebanon’s oldest madrassa.

Throughout the centuries, Lebanese rulers built castles and mosques as well as khans or caravanserais. One of the best preserved is Khan al-Franj (17th century), built by Emir Fakhr al-Din in Sidon. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Beiteddine Palace in the Chouf Mountains was built as the residence of Emir Bashir the Great, of the Chehab dynasty. Originally, this building, famous for its mosaics, was a Druze hermitage.

Some houses dating from the 18th and 19th centuries may still be seen in parts of Tripoli and Beirut. Contemporary architecture is mainly functional and not very different from what is seen in other parts of the world.

Visual Arts

As in almost all other fields, the civil war (1975-1990) is very much present in the works of many Lebanese artists.

Together with other artists, Walid Raad, whose work has been exhibited at the Documenta in Kassel, Germany, among other places, created The Archives of the Atlas Group (1989-2004), in which these artists documented or represented the civil war in many different ways. One of Raad’s best known works in this respect is My neck is thinner than a hair, which contains 245 photographs of all the car bomb attacks during the war.

Let’s be honest, the weather helped is what Raad calls a ‘notebook’ with photographs and drawings of shrapnel he collected, thus documenting, as he realized years later, all the 23 countries that had armed or sold ammunitions to the various factions fighting one another.

Khalil Joreige and Joana Hadjithomas are photographers and make videos and installations such as Beirut: Urban Fictions, Wonder Beirut, or Distracted Bullets. In these works, they try to represent what they call the people’s amnesia concerning the civil war.

In his performance Who’s afraid of representation?, Rabih Mroué wants to blur the line between what was and what could have been. Zena al-Khalil creates collages combining sweet, kitsch-like images with, for instance, that of a child carrying a Kalashnikov. Nadim Karam makes monumental sculptures representing dreamed creatures, pleasant or terrifying, or a combination of both. Alfred Tarazi paints nightmares: terrified, deformed heads or a lonely figure stared at by surrounding human shapes.

Much more direct and explicit are the works of a group of painters in the Palestinian refugee camp Beddawi, in the north of Lebanon. The canvases or murals of the majority of these artists – such as Nizar Abu Ayid, Yusuf Shams, Burhan Hussein Suleiman – are clearly politically engaged, showing armed militants, boys throwing stones, the Palestinian flag or the victims of Israeli bombs. Some of these works were commissioned by Hezbollah.

Traditional Crafts

Traditional crafts like shipbuilding – linked to the presence of immense cedar and pinewoods – have disappeared with the forests themselves. However, wooden furniture and marquetry are still made on a small scale.

The textile industry, which Lebanon owed mainly to its special methods of dyeing, underwent the same fate as the wood industry. The Lebanese royal purple was particularly famous. Nowadays, textiles are often at least partly synthetic and their production has moved to cheaper countries. Jewellery, once sold by the Phoenician traders on their travels abroad, is still made by local craftsmen.

Among the traditional crafts, the one that is probably best preserved is food preparation. From different kinds of breads, meze (appetizers), pastries, preserves, jams and pickles, rose water and orange blossom water, and everything based on olive oil (including soap), the list of traditional food products is a long one.

Sports

Lebanon is one of the few countries where both summer and winter sports are thriving. Lebanon hosted the 1959 Mediterranean Games in Beirut, the Pan-Arab Games twice (1957 and 1997) as well as the 2000 Asian Cup.

Basketball is very popular in the region and the Lebanese Basketball Federation is also a member of FIBA Asia. Lebanon’s national team has qualified for the FIBA World Championships three times from 2002 to 2010. Some of the most popular Lebanese ball-players include Fadi El Khatib and Elie Mechantaf. In October 2020, Lebanese’s national football team ranked 91 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

It would be impossible to write about popular Lebanese music without mentioning Fairuz, the singer who has been called the ‘soul of Lebanon’ and her country’s ‘ambassador to the stars’. She and her collaborators, composers Assi Rahbani and Mansour Rahbani, rose to prominence at a time when Lebanon was finding its national identity, following the end of French rule in 1946.

Fairuz was born in 1935 as Nouhad Haddad. She began her singing career as a teenager, performing in the chorus at the Lebanese radio station. It was there that she met and began working with the Rahbani brothers. She would later marry Assi, the eldest brother.

Many intellectuals and artists have left Lebanon over the centuries.

Each period of violence, each wave of repression by the then occupying power, each (civil) war was followed by a wave of emigration. Hence, the Lebanese arts developed not only in Lebanon itself – where Beirut is probably the most important cultural centre – but also in the countries where émigrés found a second home. Damascus and Cairo and, further away, Paris, London, New York, and Rio de Janeiro are thus also minor Lebanese cultural centres, especially for Lebanese literature and cinema.

In present day Lebanese literature, but also in Lebanese music, film or fine arts, the Civil War (1975-1990) and its aftermath are recurrent themes. Many artists want to remember and document these events and their aftermath, or to fight against the political and religious divisions that led to the war.

Moreover, years of violence and destruction left the Lebanese people with a deep hunger for beauty, creativity and artistic ways of expression. From the 1990s, Lebanon has witnessed a wave of artistic expression, but also the founding of various festivals such as the Salon du Livre, the Beirut International Film Festival, or al-Bustan (music) Festival

Literature

Lebanon has many publishing houses, which publish in Arabic, French and English. In 2009, UNESCO designated Beirut as World Book Capital, ‘in particular thanks to its efforts for cultural diversity, dialogue and tolerance as well as for the variety and dynamism of its programme’. Each year (with a few exceptions), Beirut hosts the Salon Francophone du Livre, the largest literary salon outside of Paris and Montreal. It also hosts an Arab and International Book Fair (representing 170 publishers and attracting 35,000 visitors). Lebanese literature is also published in countries with large numbers of Lebanese emigrants. Poetry plays an important part in Lebanese literature. Prominent musicians have written music to traditional poems, and newspapers deem poetry important.

The Nahda: a New Cultural Movement and the Shaping of Lebanese Literature

The first signs of a new cultural movement became apparent in 1957 with the foundation of Shir, a magazine for experimental poetry established by the Syrian poet Adunis (the alias of Ali Ahmad Said Asbar) and others. Poets from all over the Arab world settled in Beirut, attracted by the free press and the relatively tolerant intellectual atmosphere that reigned at the time.

In the same period, modern narrative prose began to take shape. Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad, Maroun Abboud and Yusuf Habashi al-Ashqar published their first novels and short story collections, heavily influenced by European and Russian naturalism.

Others, such as Suhayl Idris, were drawn to the existentialist movement of Jean-Paul Sartre and his group. In the second half of the 20th century, female writers began to gain ground. In 1968, Layla Baalbakki published her autobiographical feminist novel Ana ahya (‘I live’), which made her famous not only in Lebanon but across the Arab world.

The Arab defeat in the 1967 conflict with Israel and the subsequent civil war (1975-1990) in Lebanon deeply affected Lebanese society, including the cultural and literary scene. The war featured in everything that was written, be it the political novels of Suhayl Idris, the prophetic novels of Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad or the surrealistic stories of the political activist and writer Elias Khoury.

Among female writers, the war seemed to function as a catalyst and a source of inspiration. New names rose to prominence, notably Emily Nasrallah, Hanan al-Shaykh and Hoda Barakat, who would soon become known as the ‘Decentrists of Beirut’. The Decentrists tried to demystify Lebanese society by identifying the controversies underlying the political crisis. According to them, politics was not the only issue at stake and they advocated a reconsideration of traditional, pre-war patriarchal values.

In the early 1980s, a new genre of literary prose emerged. The war was still present but was stripped of the heavy ideology that had previously dominated the written word. Writers such as Hasan Daoud, Rashid al-Daif, Alawiya Subh and Iman Humaydan concentrated on the daily life of the Lebanese people during the war. The new millennium saw the emergence of a new generation of writers who were still children when the war broke out. In their literary work, they try to recover the youth that the war stole from them. Rabee Jaber is one of the most prominent representatives of this generation.

In the past 20 years, Beirut has grown into a thriving cultural and literary centre. Each year (with a few exceptions), Beirut hosts the Salon Francophone du Livre, the largest literary salon outside of Paris and Montreal, and the Beirut Arab Book Fair (representing 170 publishers). In 2009, UNESCO designated Beirut as World Book Capital, ‘in particular thanks to its efforts for cultural diversity, dialogue and tolerance as well as for the variety and dynamism of its programme’.

Modern Lebanese Authors and Notable Works

Salah Stétié (1928), writer, poet and diplomat, writes in French and has published more than 35 books, including poetry, biographies of other poets (Mallarmé, Rimbaud) and essays, such as Culture et violence en Méditerranée. He also translated Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet into French. He was awarded the Grand prix de la Francophonie in 1995. A selection of his poems was translated into English under the title Cold Water Shielded.

His works have also been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Turkish and Serbian. In 2006, he received Serbia’s Smederevo Award, the oldest poetry award in Europe. In 1996, the Arabic-language l iterary journal al-Adab published a special issue about him. He is also the subject of three documentary films.

Adunis (born 1930) is a poet, philosopher and literary critic. He founded two literary journals, Majallat Shir (‘poetry’) and Mawaqif (‘positions’). He has been named several times as a possible Nobel laureate. The first collection of Adunis’ verse in English, The Blood of Adonis, appeared in 1971 and was reissued in 1982 as Transformations of the Lover.

Gibran Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) is one of the most important writers of Lebanese origin. From the age of 12, he was raised in Boston, United States. He studied art in Paris for two years, then returned to the United States, where he live from 1912 in New York.

His name was shortened to Khalil Gibran by mistake upon his arrival in the United States, and he is known under this name outside Lebanon. Gibran’s early works were written in Arabic, but from 1918 he published mostly in English. Among his best known works is The Prophet, a book of 26 poetic essays, which has been translated into more than 20 languages.

Vénus Khoury-Ghata (born 1937) writes in French and has lived in France since 1973. A well-known and highly regarded poet, novelist and short story writer, she was awarded the Prix Mallarmé in 1987 for Monologue du mort, the Prix Apollinaire in 1980 for Les ombres et leurs cris, and the Grand Prix de la Société des gens de lettres for Fables pour un people d’argile in 1992.

Her most recent collection of poems, Quelle est la nuit parmi les nuits, was published in 2004. Her work has been translated into Arabic, Dutch, German, Italian and Russian. She was named a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 2000. Her most recent novel, Sept pierres pour la femme adultère (2007), was shortlisted for two important prizes.

Elias Khoury (born 1948), novelist, playwright, literary critic and sociologist, is considered one of the leading contemporary Arabic intellectuals and writers. In his youth, he enlisted in the Fatah movement within the Palestine Liberation Organization, then fought in Lebanon’s civil war.

His novels have been translated into many languages. For several years, he was the editor of al-Mulhaq, the weekly literary supplement of the daily newspaper al-Nahar. Among his best known books are Little Mountain, The Journey of Little Gandhi, The Kingdom of Strangers and Gate of the Sun. He lives in Beirut and New York.

Amin Maalouf (born 1949) lives in Paris and writes in French. A versatile author of novels, essays and even opera librettos, he is a compelling storyteller. Much of his work seems aimed at creating more understanding among (opposing) groups. Many of his novels are set against a historical backdrop and some of his characters are historical figures. His most important novels include Leo the African, The Rock of Tanios, which was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1993, and Balthasar’s Odyssey. Origins, translated into numerous languages, traces his grandfather’s history within the wider context of Lebanon’s and the world’s history.

Jabbour Douaihy (born 1949) is an academic, novelist and journalist. His works include Ayn Ward, June Rain, which was shortlisted for the 2008 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, also known as the ‘Arabic Booker Prize’, and Autumn Equinox.

Alexandre Najjar (born 1967), who lives in France and writes in French, is one of the most important writers of his generation. He was awarded the Grand prix de la Francophonie in December 2009. His books include a biography of Khalil Gibran, The School of War, Berlin 36, Phoenicia and Le roman de Beyrouth, about the tragic events in 1860 and thereafter.

Film, theatre and television

Theatre is a recent art form in Lebanon. The only traditional theatre – imported from Iran – is that of the Shia Muslims, who perform a ritual kind of theatre that enacts the passion of Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, in which tears are shed for the fate of Hussein and his family (ahl al-bayt). Hussein – the Twelfth Imam, revered by the Lebanese Shia – was slain in the Battle of Karbala in 680, on Ashura (the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic year).

This theatre is also found in Damascus. Around 1910, it was translated into Arabic. Since 1930, the Battle of Karbala has been enacted every year in Nabatiya southern Lebanon, on Ashura.With the rise of Hezbollah, this kind of theatre became more and more important. Today, similar plays are staged in other towns and villages in the region and have been opened to spectators from other regions and other religions. Professional actors and directors have tended to replace the former amateurs, certainly in Nabatiya.

Western-style theatre was first introduced in the 19th century, when a rich merchant, Marun al-Naqqash, commissioned a performance of Molière’s play L’Avare (‘the miser’), which was entirely sung. For a long time, this was the dominant form of theatre and several artists still mix music, song and performance. Ziad Rahbani, for example, now mainly known as a singer-songwriter, started out as a comedian.

One of the foremost playwrights and directors is Elie Karam. Born in a Muslim part of Beirut to Christian parents, he fled the civil war to Austria and Canada, where he studied dramatic arts. After the war he returned to Beirut, where he wrote and directed several critically acclaimed plays exposing controversial issues in the Middle East. His latest production, Tell Me About the War and I Will Love You, won several prestigious prizes and was staged at the renowned Avignon Theatre Festival in France in 2010.

Cinema is a popular art form in Lebanon. For such a small country, Lebanon has produced many film directors. Ziyad Doueiri, Ghassan Salhab, Nigol Bezjian and Samir Habchi are among the best known. Maroun Bagdadi, Bourhan Alaouie, Rafiq and Heini Surur are seen as the forerunners of contemporary Lebanese ‘art cinema’. Many film directors spent the civil war abroad, where most of them learned their trade.

The civil war and its aftermath are very present in their films, although the directors – perhaps because they spent a long time outside the country – mostly do not identify themselves with one party. They prefer to describe what war does to people.

The younger generation of film directors (Randa Chahal Sabbag, Nadine Labaki, Youssef Fares, Assad Fouladkar, Danielle Arbid, Philippe Aractingi, Khalil Joreige) tend to focus on different themes, often relating to the difficulties of daily life.

Music

Following the Second World War (1945-1949), Beirut established itself as the cultural capital of the Middle East, with the Lebanese music scene leading the way. Lebanese music has a distinct sound due to the country’s unique fusion of Western and Eastern influences. Even Lebanese folk compositions often reference Western contemporary music. This rich cultural mix has also influenced Lebanese dance, and from the 1970s Lebanese dancers began blending the traditional dabke with Western classical and modern dances such as ballet, hip-hop and breakdance.

During the civil war, the tradition of musical fusion continued. The alternative Western music scene was also popular and continued to be so after the war. This went hand-in-hand with a growing interest in Arabic pop, and an Arabic music industry emerged that was focused in and on Beirut. In the same period, an extensive underground music scene developed, covering blues to jazz, hip-hop to rock, metal to post-punk and psychedelic to electronic-core. In the 21st century, experimental music took hold and today, a new wave of Lebanese indie rock youth music has emerged.

Pioneers of music education

Since the creation of modern Lebanon in 1920, music has been a feature of all aspects of private and public life. Wadih Sabra, composer of the Lebanese national anthem, founded the Music School in 1910. It became the Lebanese National Conservatory in 1929, the first of its kind in the Middle East. By the middle of the 20th century, the conservatory was an autonomous institute supported by the state under the supervision of the minister of education.

From 1953 until the start of the civil war in 1975, the conservatory was a regional cultural hub, served as a national archive and music research centre, and had its own chamber orchestra directed by Raif Abillama. During the war, it was all but destroyed as instruments, documents, archives and libraries were looted or burned. It resumed its role as a national music school, archive and research centre in 1991.

In 1995, it was upgraded to a national institute for higher education and was renamed the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music. Since its inception, the conservatory has had two programmes: Western classical and Oriental classical. Modern Oriental and jazz were added later.

universities have also incorporated music into their curricula. The first university to establish a music department in the Middle East was Université Saint-Esprit de Kaslik (USEK) in 1970. Other Lebanese universities followed suit, especially after the civil war.

The new millennium brought more private initiatives to create modern music schools, which subsequently opened in the major cities of Beirut, Jounieh, Byblos, Tripoli, Zahle, Tyre and Sidon. The best established is the Mozart Chahine School of Music, which has three locations and offers a musical diploma.

Traditional music

Zajal

The Ottoman Empire, of which Lebanon was a part for several centuries until the empire’s collapse in the early 20th century, greatly influenced Lebanese culture, and these influences were fused with the previously accumulated cultural heritage of the region. This resulted in a musical tradition that shares similarities with neighbouring Syria and Palestine but is also quite distinct.

One of the oldest Lebanese music forms is today considered a living tradition, especially in rural areas. Called zajal, it is partly or totally improvised sung poetry. In most cases, it takes the form of a competition between two poets/singers or two teams, who declaim or sing verses in a colloquial dialect. The main melodies are produced by the poets themselves and supported by percussion instruments such as the daf, rikk and tabla.

Occasionally, traditional instruments such as the nay, oud or kanoun will provide the accompaniment. Zajal parties are stand-alone night entertainment, where the two teams sit at opposite tables and sing while drinking arak (an alcoholic spirit) and/or eating meze (appetizers).

The poets/singers (known as zajjalin) are usually respected social figures recognized for their talent and are invited to perform at weddings and special celebrations. The zajjalin improvise or sing the poetic discourse in verses, and the last few words are repeated as a unified chorus by most of the people present.

Although very much alive in Lebanon, zajal is not exclusive to the country and is still practised, if only rarely, in parts of Palestine and coastal Syria. Among famous contemporary Lebanese zajjalin are Chahrour al-Wadi and Rachid Nakhle, who wrote the lyrics for the national anthem, Zein Sheib, Talih Hamdan, Zaghloul al-Damour, Hanna Moussa, Anis al-Feghali, Moussa Zgheib, Asaad Said, Sayed Mohammad Mustafa, Khalil Rukoz, Victor Mirza, Sharbil Kamel, Edward Hareb, Assaad Assaad and Mouzir Khairalla.

Dalouna and Howara

Unlike zajal, dalouna is a fully sung poetry form that is usually memorized although it can be improvised as well.

Dalouna can be adapted to any occasion, whether it is happy (weddings, births), sad (funerals), nationalistic (victory, independence), social (end of a day’s work in the field, village anniversary, holiday) or even religious. It is very much alive in Palestine and Syria as well, and is similar to Jordanian and Iraqi dabke.

Although modern Lebanese Arabic pop music only borrowed elements of zajal, known as moual, it has fully embraced dalouna, and modern versions of dalouna have been sung by contemporary Arabic pop artists such as Assi al-Hillani, Faris Karam and Najwa Karam.

Howara is a purely Lebanese music form adapted from zajal. However, whereas dalouna is common to most countries in the Levant, howara is specific to Lebanon. Dalouna is a traditional Levantine dancing music and howara is a Lebanese folk dancing music and, in most cases, there is no dalouna or howara without dabke.

Dabke

Dabke is the name of a folk dance of Phoenician and Canaanite origins. Today, dabke is as much a musical style as a dance style. It is still danced at weddings and even in nightclubs, and professional dabke groups can be found all over the country.

The best known of these is Caracalla, which was founded in 1970 and established a dance school for theatrical musical and dance-based plays. It is considered the pinnacle of the marriage between Western and Oriental artistic expression and produced a genre so unique it has become known as Caracalla style.

Tarab

The word tarab has no exact translation in English, although ‘ecstasy through the enjoyment of music’ or ‘being enchanted by the music’ come close. Tarab is also the name of a modern classical Arabic music genre.

Tarab is not originally a Levantine art form; it has a long history that can be traced back to the Golden Age of Arabic music during the Abbasid era. Tarab is nonetheless very popular in Lebanon, whether in its classical form, such as Mouwashat Andalusia and Qoudoud Halabiya (from Aleppo), or in the more contemporary interpretation that was popularized in the 1960s by the Egyptian singers Um Kulthum and Abd al-Wahab.

Although the majority of modern tarab singers are Egyptians, a few Lebanese artists, such as Wadih el-Safi, who is nicknamed ‘the immortal voice of Lebanon’, have successfully ventured into the genre. George Wassouf is another popular modern tarab artist in Lebanon despite being of Syrian origin.

The Rise and Rise of Lebanese Music

Modern Lebanese music is characterized by a fusion of Western and Arab influences, reflecting the complex and multicultural nature of Lebanese society.

Fairuz

It would be impossible to write about popular Lebanese music without mentioning Fairuz, the singer who has been called the ‘soul of Lebanon’ and her country’s ‘ambassador to the stars’. She and her collaborators, composers Assi Rahbani and Mansour Rahbani, rose to prominence at a time when Lebanon was finding its national identity, following the end of French rule in 1946.

Fairuz was born in 1935 as Nouhad Haddad. She began her singing career as a teenager, performing in the chorus at the Lebanese radio station. It was there that she met and began working with the Rahbani brothers. She would later marry Assi, the eldest brother.

The trio burst onto the national stage in 1952 with the song ‘Itab‘ (‘blame’), which became their first hit.

Ramzi Salti, a Lebanon-born Stanford University lecturer who runs the podcast Arabology, which showcases music from the Arab world, told Fanack that the songs the Rahbani brothers penned for Fairuz were a departure from the lengthy pieces punctuated by orchestral interludes performed by previous icons of Arab music such as Oum Kalthoum.

Fairuz’s songs were as short as Western pop songs, three or four minutes, and she favoured a clearer vocal tone over the traditional nasal singing style of Arab music.

Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers “revolutionized Lebanese music and they revolutionized Arabic music in general”, Salti said. “People initially rejected that and thought it was too Western, that it wasn’t Lebanese at all, that she was just copying the West, but it was groundbreaking.”

The rejection did not last long and Fairuz became a national icon. She appeared regularly at the Baalbeck International Festival, along with other famous singers of the day, including Sabah and Wadih el-Safi. The Rahbani brothers composed musical plays for the occasions, in which Fairuz played a starring role.

Fairuz did not flee the country after civil war broke out in 1975, but she refused to perform inside of Lebanon during the war, instead touring abroad.

Pop Divas

In the post-war period, Lebanon has continued to export popular music to the rest of the Arab world. The 1990s and 2000s saw the rise of Lebanese pop divas such as Nancy Ajram, Haifa Wehbe and Elissa. These singers, with their racy videos and suggestive lyrics, have been magnets for controversy in the more conservative Gulf countries and elsewhere in the Middle East.

Ajram has been banned from playing in Kuwait and Bahrain. The Bahraini parliament also called for a ban on Wehbe, and the Egyptian government briefly banned a provocative movie starring the singer. Yet these incidents did nothing to dampen the singers’ commercial success. If anything, it gave them more exposure.

Soapkills and the Burgeoning underground Scene

Meanwhile, a young audience seeking more independent and edgier Arabic-language music also found its standard bearer in Lebanon, with the arrival of the indie electronica duo Soapkills.

The band, formed in 1997 by Yasmine Hamdan and Zeid Hamdan, blended classical Arabic musical influences with the sound of trip-hop artists like Portishead and Massive Attack.

Yasmine Hamdan told the New York Times that the group initially had a hard time getting radio play because she sang in Arabic. “It was seen as not cool. Either you sang traditional Arabic folk music or you sang rock in English.”

Nevertheless, Soapkills went on to become one of the most beloved acts in Lebanese independent music. After eight years, the duo split and went on to pursue successful solo careers – Yasmine in Paris and Zeid in Lebanon.

Other Musical Movements

The popularity of Soapkills precipitated a flourishing underground and independent music scene, encompassing a wide range of genres, from the jazz and bossa nova of Tania Saleh to the ensemble al-Rahel al-Kbir, or The Great Departed, which has penned satirical songs mocking the ideology of Islamic State.

Lebanon has also seen the rise of hip-hop, with artists including El Rass and Rayess Bek. Likewise, hip-hop groups have sprung up in the Palestinian camps in Lebanon and among young Syrian refugees living in the country.

There has also been an active Lebanese heavy metal scene since the 1990s, Blaakyum being the longest running group. The scene has periodically run into problems with Lebanese authorities, facing several waves of raids and arrests in search of ‘Satanic’ activities.

Arab Spring

Although Lebanon was not at the centre of the 2011 Arab Spring protests and uprisings, it was part of a wave of more rebellious musical voices coming out of the Middle East during that period.

In 2008, Zeid Hamdan recorded ‘General Suleiman‘, a reggae song directed at Michel Suleiman, then Lebanon’s president. The song’s lyrics included references to ‘militia men’, ‘warlords’ and ‘corrupt politicians’ and ended with a cry of ‘gene-gene-general, go home!’

After the release of a video for the song, Hamdan was briefly imprisoned in 2011 on charges of defaming the president. His arrest caused widespread outcry among fans. Hamdan maintained that the song was intended as a call for the president to be a force for peace, after clashes broke out between Hezbollah and rival groups in 2008.

Mashrou’ Leila

The Lebanese independent music scene has recently seen another break-out success with the rock group Mashrou’ Leila. The act, formed in 2008 by a group of students at the American University of Beirut, has found commercial success across the Middle East.

The group’s distinctive style is driven by singer Hamed Sinno’s emotive voice and the violin work of Haig Papazian. Sinno is openly gay, a rarity for a pop culture figure in the Arab world, and the band’s lyrics deal with issues of sexuality, substance abuse and political violence, topics that are taboo in much of the region. In April 2016, the group was banned from playing in Jordan, although the ban was later lifted.

The group released its fourth album, Ibn El Leil, in 2015. It debuted at number one on local iTunes channels, and reached number 11 on the international Billboard Charts, prompting the Guardian newspaper to write: ‘It’s such an impressive performance that stadiums seem not only possible but imminent.’

Architecture

Architecture is what mostly remains of Lebanon’s past. Byblos was the first city ever built entirely of stone and there are still traces of this very early architecture, going back thousands of years, and now mostly hidden under Roman ruins. Most of the architectural treasures have been damaged or even destroyed during one of the many wars that have been fought in this region over the centuries. In addition, several earthquakes have brought destruction.

Despite being in ruins, Baalbek, in the Beqaa Valley, is one of the most impressive Roman sites in the Middle East. The Great Jupiter Temple and the Great Bacchus Temple took well over a century to build, starting in 60 BCE.

Not far from these temples is also one of the two remaining Umayyad ruins, the Great Mosque, built partly with stones from the Roman temples in the 7th and 8th centuries. The other Umayyad building is in Anjar, also in the Beqaa Valley. What is left here of the Umayyad city dates back to the 8th century.

Crusader Architecture

The crusaders and those who fought them were also builders. The crusaders built churches and fortresses. One of these churches is the 12th-century St John the Baptist in Byblos, a Romanesque-style structure, although one of the portals is in typical 18th-century Arab style. Not far off is the Crusader Castle, built by the Franks in the 12th century.

In the northern city of Tripoli are the remains of the Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles (12th century). Two centuries later, the Great Mosque arose on the ruins of the crusader cathedral St Mary of the Tower. This is the oldest and largest Mamluk mosque in Lebanon. Next to it is Lebanon’s oldest madrassa.

Throughout the centuries, Lebanese rulers built castles and mosques as well as khans or caravanserais. One of the best preserved is Khan al-Franj (17th century), built by Emir Fakhr al-Din in Sidon. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Beiteddine Palace in the Chouf Mountains was built as the residence of Emir Bashir the Great, of the Chehab dynasty. Originally, this building, famous for its mosaics, was a Druze hermitage.

Some houses dating from the 18th and 19th centuries may still be seen in parts of Tripoli and Beirut. Contemporary architecture is mainly functional and not very different from what is seen in other parts of the world.

Visual arts

As in almost all other fields, the civil war (1975-1990) is very much present in the works of many Lebanese artists.

Together with other artists, Walid Raad, whose work has been exhibited at the Documenta in Kassel, Germany, among other places, created The Archives of the Atlas Group (1989-2004), in which these artists documented or represented the civil war in many different ways. One of Raad’s best known works in this respect is My neck is thinner than a hair, which contains 245 photographs of all the car bomb attacks during the war.

Let’s be honest, the weather helped is what Raad calls a ‘notebook’ with photographs and drawings of shrapnel he collected, thus documenting, as he realized years later, all the 23 countries that had armed or sold ammunitions to the various factions fighting one another.

Khalil Joreige and Joana Hadjithomas are photographers and make videos and installations such as Beirut: Urban Fictions, Wonder Beirut, or Distracted Bullets. In these works, they try to represent what they call the people’s amnesia concerning the civil war.

In his performance Who’s afraid of representation?, Rabih Mroué wants to blur the line between what was and what could have been. Zena al-Khalil creates collages combining sweet, kitsch-like images with, for instance, that of a child carrying a Kalashnikov.

Nadim Karam makes monumental sculptures representing dreamed creatures, pleasant or terrifying, or a combination of both. Alfred Tarazi paints nightmares: terrified, deformed heads or a lonely figure stared at by surrounding human shapes.

Much more direct and explicit are the works of a group of painters in the Palestinian refugee camp Beddawi, in the north of Lebanon. The canvases or murals of the majority of these artists – such as Nizar Abu Ayid, Yusuf Shams, Burhan Hussein Suleiman – are clearly politically engaged, showing armed militants, boys throwing stones, the Palestinian flag or the victims of Israeli bombs. Some of these works were commissioned by Hezbollah.

Traditional crafts

Traditional crafts like shipbuilding – linked to the presence of immense cedar and pinewoods – have disappeared with the forests themselves. However, wooden furniture and marquetry are still made on a small scale. The textile industry, which Lebanon owed mainly to its special methods of dyeing, underwent the same fate as the wood industry.

The Lebanese royal purple was particularly famous. Nowadays, textiles are often at least partly synthetic and their production has moved to cheaper countries. Jewellery, once sold by the Phoenician traders on their travels abroad, is still made by local craftsmen.

Among the traditional crafts, the one that is probably best preserved is food preparation. From different kinds of breads, meze (appetizers), pastries, preserves, jams and pickles, rose water and orange blossom water, and everything based on olive oil (including soap), the list of traditional food products is a long one.

Sports

Lebanon is one of the few countries where both summer and winter sports are thriving. Lebanon hosted the 1959 Mediterranean Games in Beirut, the Pan-Arab Games twice (1957 and 1997) as well as the 2000 Asian Cup.

Basketball is very popular in the region and the Lebanese Basketball Federation is also a member of FIBA Asia. Lebanon’s national team has qualified for the FIBA World Championships three times from 2002 to 2010. Some of the most popular Lebanese ball-players include Fadi El Khatib and Elie Mechantaf. In October 2020, Lebanese’s national football team ranked 91 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Lebanon’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: