Introduction

The armed forces of the young independent State of Lebanon took part in the Civil War of 1948 against the newly declared State of Israel with only a thousand troops, the smallest Arab contingent. The Lebanese Armed Forces at that time consisted of 3,500 men. They undertook some half-hearted raids into northern Israel but were quickly repelled by Israeli forces. It was said that Israel had made a pre-war deal with the Maronite generals in Lebanon to show restraint.

Lebanon signed a ceasefire agreement with Israel in 1949, shortly after Egypt. At that time, nobody could have imagined that the country would become a battle lab for asymmetrical warfare and counterinsurgency tactics. And yet, it is no exaggeration to describe the successive conflicts that engulfed the small country as pivotal for global military developments.

After the Arab-Israeli War of 1948-1949 and the Palestinian Nakba, some 100,000 Palestinian refugees ended up in Lebanon. They added to the increasing tensions between Christians and Muslims that already existed in the country. In the 1950s, the political situation worsened when many Muslims supported the Arab nationalist movement founded by the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Maronite Christians under President Camille Chamoun were less taken with the Arab nationalism that, among other things, led to the short–lived ‘fusion’ of Egypt and Syria into the United Arab Republic in February 1958.

In July of that year, Chamoun felt threatened by internal unrest and Nasser’s ambitions that he called on military assistance from the United States. With the Sixth Fleet, the United States had a large military presence in the Mediterranean, so an expeditionary force of marines and airborne troops flown in from Germany was quickly assembled. They landed on the coast near Beirut and dug in at the airport. The gunboat diplomacy worked: Chamoun had to resign, but the political unrest died down. Within four months, the American forces withdrew to their ships and barracks. Losses were minimal. These were halcyon days for the American forces in Lebanon. That would, of course, change.

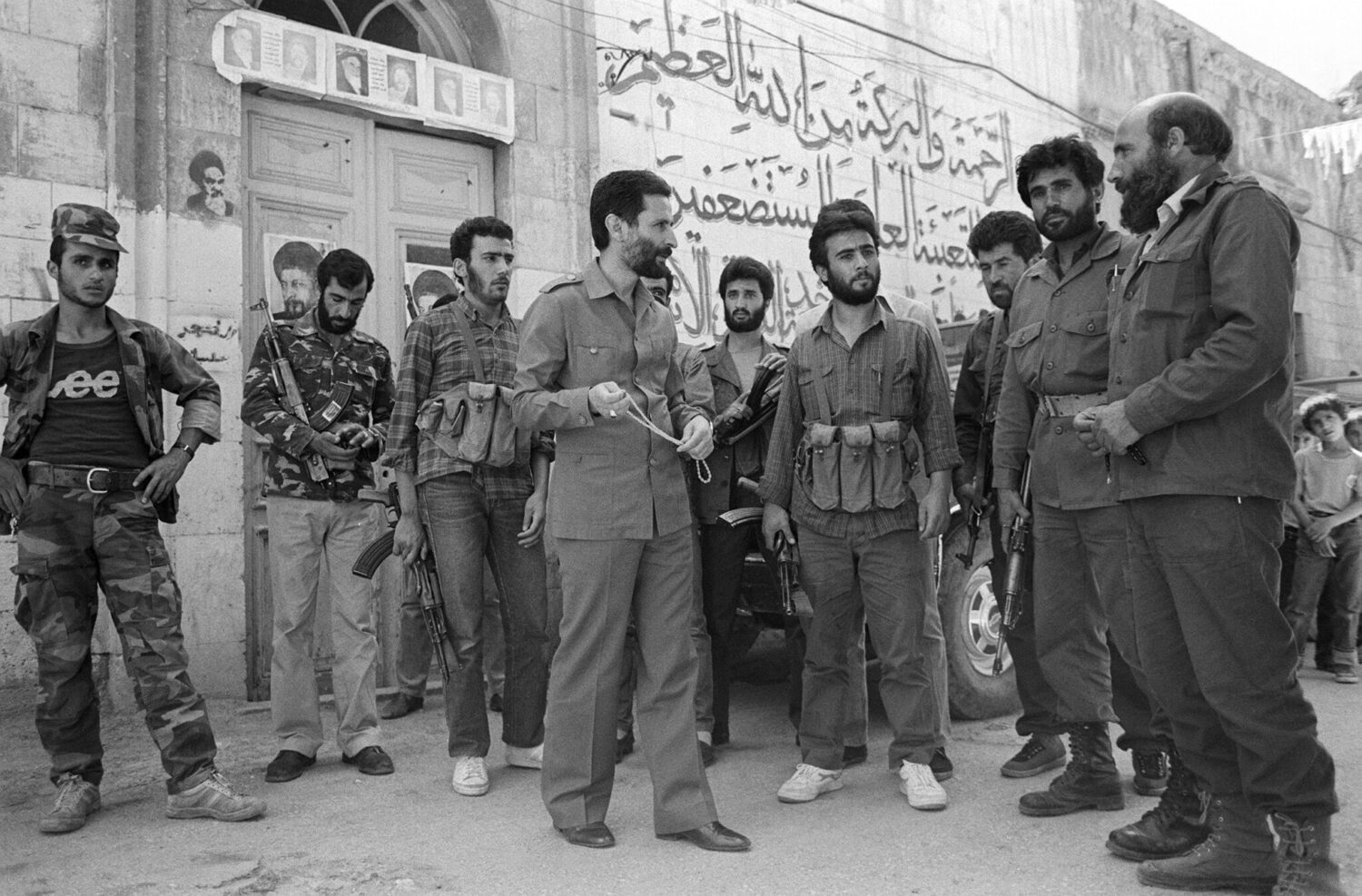

Fatah in Lebanon

In 1967, there was a new influx of refugees due to the hostilities during the June War. In 1970, more Palestinians sought refuge in Lebanon after King Hussein had ousted Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Fatah from Jordan. The PLO, which consisted of some eight to ten loosely cooperating organizations with different religious and ideological profiles, profited from the Lebanese government’s weakness and the consequent power vacuum in large parts of the country, including the south. Guerrillas started to raid military and civilian targets in northern Israel, followed by Israeli military actions on Lebanese soil. Among the targets were PLO facilities and officials – in Beirut, Sidon, and elsewhere.

From a military point of view, the outcome of this conflict was never decided. When in March 1978, Fatah militants infiltrated northern Israel, hijacked two buses, and killed and wounded Israeli citizens, Israel decided to show it had escalation domination. Three days after the Fatah raid, the Israeli army swept through southern Lebanon up to the Litani River with 25,000 men.

They withdrew a few months later, leaving the area to be patrolled by the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) and the Christian militia South Lebanon Army (SLA) supported financially and armed by Israel and led by a former major in the Lebanese Armed Forces, Saad Haddad. However, UNIFIL and the SLA failed to stop the attacks by Fatah, which was strengthened by the chaos caused by the disintegration of the rest of Lebanon, where a full-blown Civil War raged from 1975 on.

In 1982, the Israeli Armed Forces invaded Lebanon again. This time they went all the way to Beirut, which was besieged for several weeks. At first glance, the offensive in the south of Lebanon looked like a reprise of the operations of 1978. The presence of UNIFIL and SLA did not influence the Israeli advance. However, there was one large difference for the substantial Syrian military presence in the Beqaa Valley presented a military factor to be reckoned with.

Israeli technological superiority

In 1981, the Syrian army had closed the ‘gate to Damascus’ with armored forces under a network of Soviet-type surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), like the mobile SA-6 and SA-9. These sophisticated missiles had cost the Israeli Air Force dearly during the War of 1973 (the October War). But the Israeli forces had worked out a way to counter the threat: by using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), at that time called Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPVs).

Unnoticed, these reconnaissance planes kept track of the SAM batteries, not just their exact location but also the early warning and fire-control radars’ electronic fingerprint. This allowed Israeli electronic warfare systems to blind the SAM batteries and neutralize them with airstrikes and even long-range artillery. This tactic set a standard and was subsequently copied the world over.

With the protective umbrella thus removed, the Israeli fighter-bombers had gained air superiority were it not for the large-scale counterattack mounted by the Syrian Air Force. But this move had been anticipated. Israeli E-2 Hawkeye airborne warning and control aircraft, equipped with a long-range radar and command and control equipment, saw a hundred MiG-21 and MiG-23 interceptors approaching the airspace over the Beqaa Valley.

The pilots of these aircraft relied heavily on information provided by ground control in Syria. Many of the communication links between these ground controllers and air-to-air fighters had been jammed by Israeli electronic warfare equipment. This critically reduced the situational awareness of the Syrians. On the other hand, the Israeli Hawkeyes could freely vector F-15s and F-16s towards the disabled Syrian opponents. Also, RPVs were flying over Syrian airbases observing when MiGs took off. The result was remarkable: eighty MiGs were destroyed, with no Israeli losses.

Fearing annihilation, hundreds of Syrian tanks withdrew from the Beqaa Valley into Syria. But Israeli technological superiority and air supremacy did not guarantee victory over PLO/Fatah and Shia/Amal militia. The Israeli armored columns stopped on Beirut’s outskirts, where some 20,000 PLO fighters had sought and found refuge in the built-on areas.

Although some Israeli detachments penetrated the city, they were reluctant to fight in the urban terrain, which is sometimes described as ‘the great equalizer since it neutralizes technological superiority. Instead, the quarters where PLO and other Muslim militia had battled Christian militia and the Lebanese army for years were bombarded from the air, from the sea, and by heavy artillery. Christian militias did enter Muslim parts of the city.

Sabra and Shatila

With the negotiated eviction of Fatah from Beirut to Tunis and some other Arab countries in August 1982, and the arrival of international peacekeepers, mostly French and American, the Israeli army prepared to withdraw. Things took a turn for the worse after the Phalange and President-elect leader, Bashir Gemayel, was killed in a bomb attack. Israel had hoped Gemayel would have enough authority and support to end the Civil War and become an Israeli ally.

Immediately after Gemayel’s assassination, Israeli troops allowed Phalange militiamen to enter two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila. That day they killed an estimated two thousand civilians, who – after their forced departure – were no longer protected by Fatah fighters. With more international peacekeepers’ arrival, the Israeli forces withdrew to the south but kept a military presence between the Awali River and the Israeli border.

For the international peacekeepers, there was not much peace to keep, however. The political situation differed substantially from the American marines and paratroopers’ environment in 1958. The Battleship New Jersey pounded the hills east of Beirut routinely, but gunboat diplomacy had lost its effectiveness.

Suicide bombings

The use of robotic planes was not the only novel tactic tested in the complex conflict; the strategic use of suicide bombers was another. Suicide attacks for military purposes or ideological reasons were, of course, not a novelty. But at this stage in the Civil War, desperate Japanese tactics against American aircraft carriers some forty years earlier did not play an important role in the American and French military’s minds. They feared landmines, snipers, and rocket attacks, not trucks laden with explosives.

On 18 April 1983, a van smashed into the American Embassy, and its driver detonated a ton of explosives. Some 60 diplomats, service members, and visitors were killed. Lessons were not learned. On 23 October 1983, a Mercedes truck with the equivalent of 12,000 kilos of TNT drove to the Marines headquarters on the edge of the International Airport.

It circled a few times on a parking lot to gain speed and smashed through the barbed wire at the gate. The truck rumbled into the building and detonated the explosives. The building collapsed, killing 241 American service members. A few minutes later, another truck bomb exploded in the French headquarters, killing 58 parachutists.

Suicide car bombs had been used in the conflict before, but these were employed against tactical targets such as Israeli intelligence personnel. However, the United States Marines headquarters and the French barracks were strategic targets: the massive loss of life amongst peacekeepers had a crumbling effect on the public support at home for these missions.

It took some time, but at the end of the day, the bombings led to the withdrawal of the Phalange and the Israelis’ most potent friends. In the weeks after the bombing, French and American aircraft bombed diverse targets east of Beirut. But this could not erase the feeling of stunning vulnerability of modern forces against such crude weapons.

There was more to be frustrated about: the planners of these suicide attacks were very difficult to track, let alone apprehend and try. There was a range of suspects: Palestinian splinter groups, Shiite militia, Syrian or Iranian intelligence services, or shifting alliances between these.

Lebanese tactics and Israeli vulnerability

Israeli forces were forced to withdraw from southern Lebanon by mounting losses inflicted, mostly by Hezbollah. In 2000, the last Israeli soldier left Lebanese soil – although Hezbollah claims that the Shebaa Farms, which remains under the control of the Israeli military, is Lebanese territory.

The situation in the border area remained tense afterward. Hezbollah moved freely in the hills and villages south of the border. Israel thought it was safe behind a high-tech border, equipped with the latest intelligent sensors, automatic weapon stations, and frequent patrols.

But, as so often proven in warfare, one cannot rely solely on sophisticated systems – the creativity of the human brain to outfox machinery should not be underestimated. In 2006, Israel underestimated Hezbollah. In 2005, the highest Israeli military authority, General Dan Halutz, divulged his armed forces’ doctrine: ‘We want to be the first to know, the first to understand, the first to decide and the first to act.’

According to this concept of operations, the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) could choose the time and place to act decisively against all opponents, including Hezbollah. ‘Training and technology allow us to attack terrorists pre-emptively whenever they approach the Lebanese border.’ These statements displayed a lot of confidence. However, this confidence was shattered when Hezbollah commandos penetrated the high-tech barrier on the Lebanese border and sabotaged a camera.

When a called-in Israeli patrol approached the defunct sensor, the trap sprung. Eight Israeli soldiers were killed in the ambush, and two were taken prisoner.

Immediately after the ambush, Israeli military commentators stated that the high-tech border had proven to be a ‘Maginot Line’ and that the IDF had relied on it too much. This techno-optimism was not limited to the border defenses but also applied to the so-called Tzayad Digital Army Program (DAP), the army’s total digitization. Israeli generals complained that the budget for this type of fancy program always came at the expense of the funds for simple training.

From a tactical viewpoint, the Hezbollah ambush was a success. More successes would follow. For example, when the elite Egoz Reconnaissance Unit crossed the border to occupy the village of Bint Jbeil under cover of darkness, they encountered heavy resistance. Apparently, the Hezbollah fighters were equipped with night vision goggles and had followed the approaching columns of Israeli soldiers.

It took three days to take the village that was only a few kilometers from the border. Hezbollah made extensive use of anti-tank missiles, which inflicted damage on the Israeli Merkava tanks, considered by military analysts the best in the world.

The Israeli response did not take long to materialize. The Israeli Air Force started to pound the area in Beirut where Hezbollah had its power base. Neighborhoods were turned into rubble. Although the Israeli intelligence services had been able to locate the larger rocket launchers in Hezbollah’s inventory, till the last stage of confrontation, Hezbollah could pound the northern part of Israel with rockets and artillery grenades. Whether Hezbollah’s boldness was a strategic success remains a topic of discussion. Several experienced Hezbollah fighters were killed, and the infrastructure was badly damaged.

During the last 50 years, Lebanon has been a proving ground for military tactics: insurgency and counterinsurgency, air operations, et cetera. Armed forces the world over has studied what happened in this arena. Mostly these were military interactions by foreign players: Israel, PLO, Syria, United States, United Nations, and Iranian proxies. Most of the time, the Lebanese army was an outsider in its own country.

That the Lebanese army is, however, a force to reckon with was proven in 2008. The fighting started on May 20, 2008, when a Lebanese police unit entered the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp to search a house. Ten days later, the Lebanese army undertook a ground offensive, supported by artillery and tanks – reportedly with US support.

After the fighting had died down in this camp in northern Lebanon, the fighting spread to other camps in the south of the country. Also, bombings took place in Beirut, and it is said that an explosion that killed 6 Spanish UN personnel on June 24 was the work of the Salafist Fatah al-Islam.