Introduction

The population of Lebanon during the first half of 2021 is estimated at 5.26 million, according to the CIA World Factbook.

No official census has been conducted for the population in Lebanon since 1932, when it was found that their number is about 875.25 thousand people and that the percentage of Christians is close to 53%. According to unofficial statistics, including a census conducted in 1956 AD, the population was estimated at 1.411 million, distributed by approximately 54% for Christians, compared to 44% for Muslims.

The conduct of a census in Lebanon has been a very sensitive issue due to the balance between the religious components of Lebanese society and the sectarian divisions in the country. In addition to the pressures that some groups may exert if the statistics highlight a major demographic shift.

Despite this, a survey conducted by the Central Statistics Department, and its results were announced at the end of 2019 AD, showed that the population of Lebanon during the 2018-2019 survey period was estimated at 4.8 million, distributed between 80% of the Lebanese and 20% of non-Lebanese. This excludes those who live in non-residential units, such as army barracks, refugee camps, neighbouring settlements and informal settlements.

Official sources estimate the number of Lebanese residing in the country, at the beginning of 2020 AD, at about 3.8 million Lebanese, and research sources estimate the number of non-Lebanese residents at about 3.8 million, distributed among various nationalities, including refugees, immigrants, Arab and foreign workers, and stateless persons. According to population estimates for the year 2020 AD, Lebanese society is divided equally between males and females, with a relative increase in the number of males estimated at only a few thousand.

Table showing estimates of the distribution of the non-Lebanese population.

| Non-Lebanese | Number (people) |

| Syrian refugees (registered and unregistered) | 1,500,000 |

| Illegal workers and asylum seekers, Arabs and foreigners, entering the transit | 450,000 |

| Old Palestinians residing since before the Arab Spring | 425,000 |

| Syrian workers before the crisis, and internally displaced persons with their families who are not refugees | 350,000 |

| Displaced Iraqis and Syrians (Christians) from well-off families | 300,000 |

| Foreign domestic workers | 250,000 |

| The hidden, the non-naturalized, and refugee children born without an identity | 200,000 |

| Arab and foreign workers who are not Syrians (Egyptians, Sudanese…) | 100,000 |

| Palestinian refugees from Syrian camps (Yarmouk camps, Palestine…) | 100,000 |

| Iraqi refugees from Syria and Iraq | 100,000 |

|

Source: Dr Ali Faour, four million refugees, the population explosion, will Syria remain? Will Lebanon Survive ?, GDE Geographical Foundation and the Center for Population and Development CPD, p. 242. |

|

In the year 2019 AD, population studies published estimated the country’s population growth rates at 3.6% in Lebanese villages and 3.5% in the capital, Beirut.

Arabic is the official language, in addition to French, English, and Armenian as widespread languages. Arabs constitute 95% of Lebanon’s total population, while Armenians make up 4%, and the others 1%. It is noteworthy that many Lebanese Christians do not consider themselves Arabs but are descendants of the ancient Canaanites.

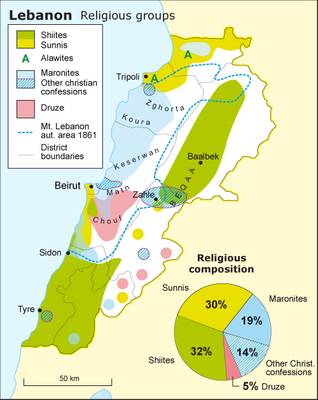

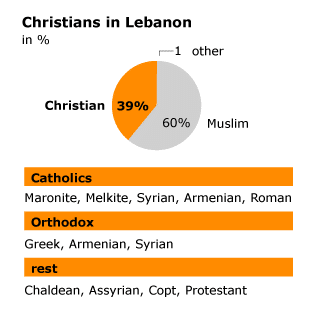

It is estimated that 61.1% of the population of Lebanon are Muslims (30.6% are Sunnis, 30.5% are Shiites); While Christians constitute 33.7% (Maronite Catholics, the largest Christian group); Druze 5.2%, and very few Jews, Baha’is, Buddhists, and Hindus (2018 estimates).

In a report by the Lebanese Information Center, the percentage of Muslims (including the Druze sect) was estimated at 65.47% in 2011 AD, while the percentage of Christians with different sects reached 34.35%.

Age Groups

Lebanon is a very young country with a majority of the population, as the survey conducted by the Central Administration of Statistics indicates that the percentage of those in the age group 0-14 years is 24% of the total population, while the percentage of the elderly aged 65 years and over was 11 % Of the total population, thus resulting in an age dependency ratio of 54%.

The working-age population (15-64 years) constituted 65% of the total population. Their percentage reached 68% in the Batroun district, followed by Keserwan, Al-Matn, and Al-Koura.

The survey showed that the marital status of residents from the age of 15 years and over, the percentage of married people reached 55.1%, 36.4% have never been married, and 8.5% widowed, divorced or separated.

Early marriage constituted less than 4% of residents between the ages of 15 and 18 years, and married women in this age group constituted 7% of all women in the same age group.

The average family size in Lebanon was 3.8 persons, down from 4.3 in 2004. At the district level, the survey revealed that Akkar has the largest average family size with 4.8 members, compared to Jezzine, which recorded the smallest average of 3.3 members. In contrast, the average family size in the capital, Beirut, was 3.4 members.

A Lebanese head of household heads 85% of families in Lebanon, a non-Lebanese head of household heads 15% of families, and women are headed by 18% of families, while men are headed by 82%.

32.4% of the Lebanese population, the Lebanese, do not currently reside in the place of their registration. The largest percentage of those who do not reside in their registration was 64.9% in the district of Jezzine, and the lowest percentage in Matn 10.7%, while the capital, Beirut, 58.4%.

The average life expectancy is estimated at 78.53 years for the total population (77.12 for males and 80 for females), and the proportion of the elderly is growing. The fertility rate was 1.71 births per woman.

Areas of Habitation

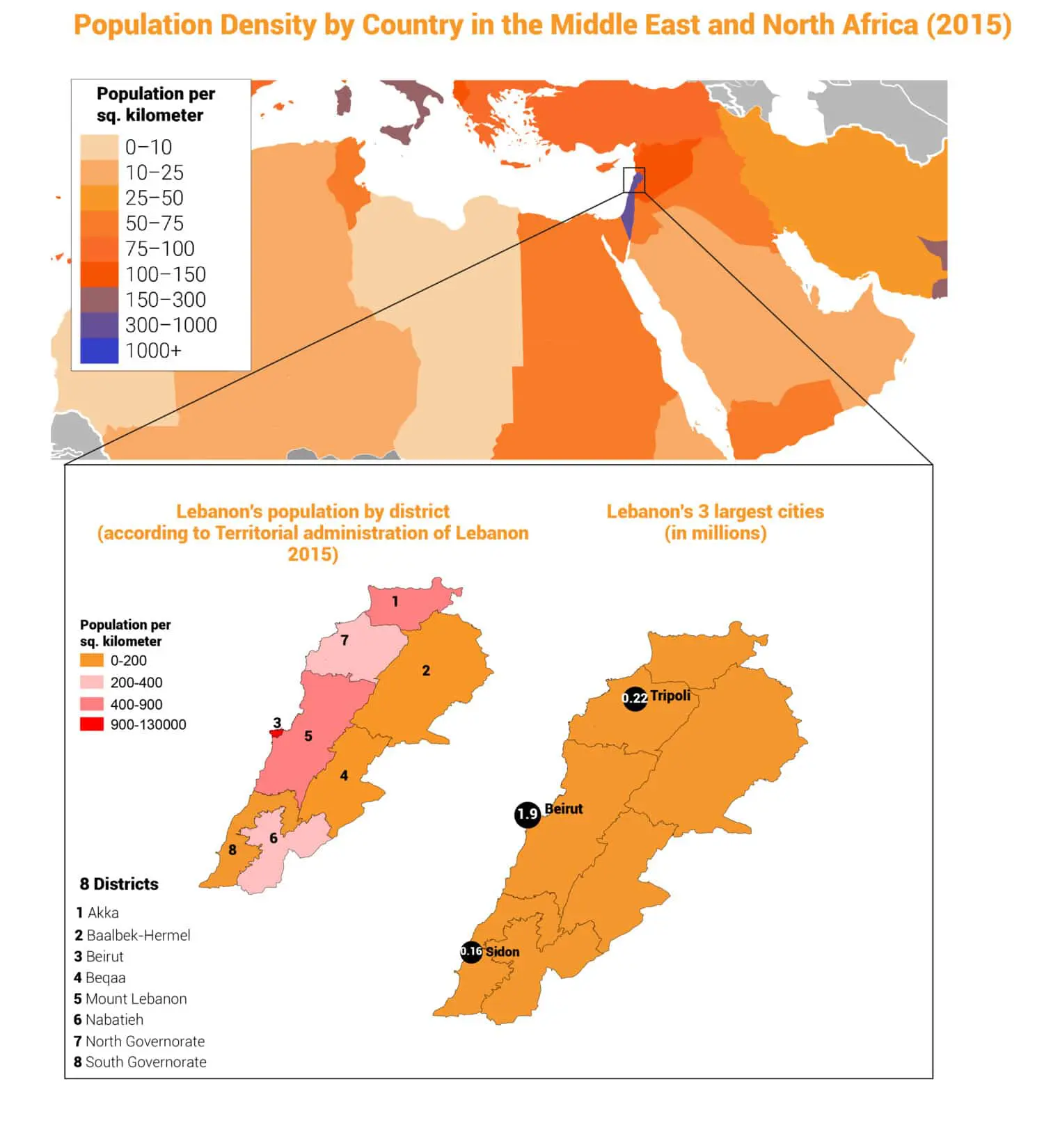

Lebanon is a densely populated country (653.15 people/km) according to population estimates in 2020 AD. The majority live in urban areas (88.6%).

Lebanon is divided into six governorates or regions (from north to south): North Lebanon, Mount Lebanon, Beirut Hermel, Bekaa, South Lebanon and Nabatiyeh. These, in turn, are divided into 25 districts. There are more than 900 municipalities in Lebanon, and each municipality has its own local government or municipal council, which are grouped into about 37 municipal federations.

The population of Lebanon is distributed according to regions, and the Mount Lebanon Governorate included the largest percentage, about 42% of the total population, while the smaller percentage was that of the Baalbek Hermel Governorate, which included only 5.1% of the population, while the capital Beirut included 7.1%.

At the district level, the Baabda district ranked first in terms of population distribution, as it comprised 11.4%, and Bcharre district ranked last with 0.5% of residents.

In 8 of the 26 districts, the share of non-Lebanese in the population exceeded their proportion at the national level. Their percentage is highest in Beirut (30.9%), where the percentage of domestic workers is the largest in Lebanon.

Ethnic and Religious Groups

The Lebanese form a mixture of cultures and ethnic groups, which has been evolving for thousands of years. Their diversity is an essential component of the Lebanese nation, characterized by a large (though decreasing) number of Christians from the very early days of Christianity.

Lebanese are descendants of the Canaanites or Phoenicians. They also descend from Arabs – either the nomads (Arabiyun/Badu) who traveled through the region since early times or the Muslims who, coming from the Arab Peninsula, conquered the region in the 7th century (see the Arab conquest).

Today, both Muslims and Christians – the latter being the oldest religious community in Lebanon – sometimes describe themselves as Arabs, referring to shared roots with the other Arab communities in the Middle East. In this respect, Lebanon takes pride in being one of the League of Arab States’ founding fathers.

Lebanon is also home to Assyrian, Jewish, Persian, Armenian, Greek, Kurd, and other minorities. Some have lived in Lebanon for centuries. Lebanon does not have a state religion. Article 9 of the Constitution guarantees an ‘absolute freedom of conscience.’ It states that ‘the State respects all religions and confessions and guarantees and protects the freedom of conscience, providing they do not disturb public order.’

Lebanon officially recognizes eighteen religious communities, most of which are represented in Parliament. They all have their own laws and tribunals as far as personal status matters (marriage, divorce, inheritance). The Registry Office records the inhabitants’ religion. However, the last official census was held in 1932, and the figures concerning religion distribution in Lebanon are estimates.

Population Change

While Christians constituted the majority of the population of Lebanon (53 per cent) in 1932, compared to 44 per cent for Muslims (the last official population census) and 54 per cent in 1956, compared to 44 per cent for Muslims in unofficial statistics.

However, a demographic study conducted in 2011 by a Beirut-based research company indicated that 21 per cent of the population is Maronite Christian, 54 per cent is Muslim (divided equally between Sunnis and Shiites), 8 per cent is Roman Orthodox, 5 per cent is Druze, 4 per cent is Roman Catholic, and the remaining percentage is made up of minor Christian sects, Jews, Bahais, Buddhists and Hindus. These figures were also adopted by the US State Department’s 2011 International Religious Freedom Report.

Sources indicate that the changes in the ethnic structure are due to waves of migration, economic and political considerations, and Lebanon’s geographical location, internal conflicts, and external interventions.

According to the CIA World Factbook, 61.1% of the Lebanese population are Muslims (30.6% are Sunnis, 30.5% are Shiites). Christians constitute 33.7% (Maronite Catholics, the largest Christian group); Druze 5.2%, and very few Jews, Baha’is, Buddhists, and Hindus (2018 estimates).

Relations between Groups

Lebanon is often compared to ethnic and religious mosaic. The delicate balance between the groups is essential for the nation’s existence. Throughout the centuries, long periods of peaceful coexistence between the groups, even of harmony, have alternated with episodes of tension, culminating in armed conflicts or even massacres.

Tensions and conflicts occurred between Muslims and Christians and between Muslims of various schools or between different Christian sects. Most of the time, these clashes were related to land or power disputes between clans rather than religious matters.

And more often than not, local outbreaks of violence were exacerbated or even caused by international tensions and the clashing interests of more powerful nations.

The (Sunni) Mamluk rulers (late 13th – early 16th century) persecuted the Shia, not only because they were Shia but also because they were thought to have helped the earlier invaders, the Mongols.

Under the Ottoman Empire (1516-1920), when Sunni Islam was the main religion, Maronites and Druze generally enjoyed more freedom of conscience than Shia, but there were also periods of greater tolerance – and this, too, was partly inspired by geopolitical circumstances.

During the 19th century, when their empire began to crumble, the Ottomans started to practice a divide and rule policy, setting the communities against one another. The European powers, sensing there would be spoils to be taken once the Ottoman Empire’s disintegration was complete, interfered as well.

The combination of these two factors led to conflict and bloodshed. Druze and Maronites clashed more than once. Some of these clashes developed into massacres, leaving deep wounds in the communities.

The Constitution

During the French mandate (1920-1946), parliamentary seats and ministerial or administrative functions were divided between the religious communities per their size. This led to an extremely complicated and rigid system that is a slightly modified form. It is still in force today and perpetuates the country’s religious partitioning, despite repeated proposals to introduce a secular system. The current Constitution describes it thus: ‘Until the Chamber enacts new electoral laws on a non-confessional basis, the distribution of seats is according to the following principles: a) Equal representation between Christians and Muslims; b) Proportional representation among the confessional groups within each religious community; and c) Proportional representation among geographic regions.’

This codified way of power-sharing comes on top of a traditional, more informal clan structure. Here, dynasties of prominent families (like the Maan, the Chehab, the Jumblatt, and the Gemayel) represent (or, in the past, ruled) their communities. These are defined more by geography and family ties rather than by religious lines.

The Civil War (1975-1990) can be considered partly as an exacerbation of the partitioning along religious lines. The war started within a context of extreme tension between Muslims and Christians because of the presence on Lebanese soil of many Palestinian refugees, plus the headquarters of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and its armed forces. International tensions and meddling only made things worse. During these years, most communities in Lebanon formed their own militias, and sometimes more than one. At times internal strife seemed omnipresent, as enemies and allies kept changing.

In the early 1990s, on the whole, peace returned to the country. Lebanon’s mosaic of identities holds a prominent place. However, although there is a tendency to downplay the importance of religious differences, some Lebanese still identify more strongly with their own separate communities than the Lebanese nation. It is difficult to ignore the eighteen recognized religious communities. It is compulsory to register with one of them to be allowed to vote, go to school, or obtain a marriage permit.

Demographic Change

However, during the past decades, the religious or communitarian landscape has been profoundly modified by demographic changes. The proportion of Christians – in particular Maronites – has been decreasing; conversely, the number of Muslims – in particular the Shiites – has clearly been on the rise.

An explanation is that Maronites generally belong to the middle class, are better educated (because of the Jesuit educational facilities in the country) and financially better off than the Shiites, who traditionally belonged to the ‘poorest of the poor’ of the country, with a high percentage of illiteracy (although this is changing). As a consequence, Maronite families are much smaller than Shia.

Their numbers are also diminishing steadily due to emigration. The Maronites belonged to the ruling class – first sharing power with the Druze, later with the Sunnis. This is also changing, among other factors, due to the rise of Hezbollah, who first appeared in the mid-1980s and grew rapidly in popularity and in political and military strength – which was visible in the streets of Beirut as recently as 2008. Today, ministers belonging to or allied with Hezbollah make up almost one-third of the cabinet posts.

Communal tensions – which, particularly in Lebanon, are also determined by conflicts and balances of power in the region and the world – are still high. Yet a dialogue between the groups is on-going.

Shiites

Shiite is a generic term for several heterodox communities in Islam (making up circa 15 percent), who distinguish themselves from orthodox Sunni Muslims through their belief that Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law, was the first imam and rightful successor to Muhammad. Shiites do not recognize the Sunni caliphs as leaders of their community. Instead, their leader must come from a line of imams descending from Muhammad.

Over the centuries, the Shiite communities developed various own doctrines and traditions. In the Islamic world, Shiites often live in closed communities in rural and mountainous regions, and to a lesser extent, in large urban conglomerations. They form a minority group (save for in Iran and Iraq) surrounded by Sunnis and are often persecuted. The most important Shiite communities in Lebanon are the Druze, the Ismailis, and Imamites (or Twelvers).

During the Civil War, the latter evolved from a discriminated marginalized community into one of the most powerful groups in Lebanon due to their alliance with Shiites in Iran and through their political and military organizations Amal and Hezbollah. Shiites predominantly live in southern Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley, although many have settled in southern Beirut since the 1960s, living in slums dubbed the ‘belt of misery’.

Time and again, the Lebanese Shiites were persecuted by the region’s rulers, starting with the (Sunni) Mamluks, who were in power between the 13th and 16th centuries. They tried to convert the Shiites. Those who did not hide in the mountains were killed. It took the Shia community a long time to recover.

The Ottomans, who ruled over the Middle East from the 16th to the early 20th century, did not always display non-Sunni Muslims’ tolerance. Historically, this explains why the Shiites lived mainly in the mountains, as did the Maronites and the Druze.

Several developments contributed to the Shia’s rise in power. One was the creation, in 1968, of the Higher Shia Islamic Council by Iranian-born Imam Musa al-Sadr (he disappeared in 1978 during a stay in Libya). The second was creating the Amal movement and, following a political rift, of Hezbollah (Hizb Allah, Party of God) in 1982. The origins of Hezbollah go back to Israel’s military occupation of southern Lebanon.

It was the only Lebanese militia not to disarm after the Civil War (Palestinians did not disarm either). According to Hezbollah and its supporters, this is the only way to prevent Israel from invading the country again. Not all Lebanese share this view, however. This aside, Hezbollah, led by Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, is much more than an armed organization. It also provides social support for the downtrodden and, for all these reasons, constitutes a political power to be reckoned with.

Sunnis

From the very beginning of the migration of Muslims to the region in the 7th century, the majority of Lebanese Sunnis resided in the urban centres, mostly in West Beirut, in Sidon (Saida) and the extreme south of Lebanon, as well as around Tripoli (Tarabulus) in the north and Baalbek in the east.

Throughout the centuries, until the French arrival, the Sunnis were often associated with the country’s rulers. This tacit alliance went back to when the power in the region was in the hands of the (Sunni) Mamluks and (Sunni) Ottomans.

Although today the Prime Minister still has to be Sunni (whereas the President of the Republic belongs to the Maronite community and the Chairman of the Parliament to the Shia), their political influence has weakened due to the rise in power of the Shiites and the Hezbollah party, which has become a strong military and political power over the years. Still, the Sunnis in Lebanon are far from powerless, if only because most Sunni Arab countries back them.

When one of their leaders, the former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, was murdered in February 2005, many fingers pointed towards Syria. Hariri’s death caused an outcry, and not just amongst the Lebanese Sunnis. Protest against this political crime united most communities in their protest against this political crime and, except for most of the Shiites, against the Syrian occupation, which came to an end the following year.

Druze

Originally, the Druze sect came from Egypt in the 11th century. It is considered an offshoot of Ismaili Islam, a branch of Shia Islam, but very different from mainstream Shia. The name Druze probably derives from one of their first leaders, Muhammad al-Darazi.

The Druze, persecuted by the Sunni Mamluks of Egypt, took refuge in the mountains of Syria and Lebanon, where they established themselves mostly in and around the Chouf Mountains, east and south of Beirut.

The Druze community’s leadership in Lebanon has traditionally been shared by three clans, the Jumblatt, the Yazbak, and the Arslan families. At present, Walid Jumblatt (son of the legendary Kamal Jumblatt, who was murdered in 1977) is the (political) leader of the Druze. His position is seemingly uncontested.

Alawites

Alawites are followers of the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law Ali and, as such, belong to the Shia branch of Islam. However, they have their own rites and systems of beliefs and are often considered heterodox by Sunni and Shia. The Alawites, who are also to be found in Turkey and Syria, form a tiny minority in Lebanon.

In Syria (where they used to be a poor rural minority), they are strongly represented among the military. They have become more urban since the Alawite Hafiz al-Assad took power there in 1970. In Lebanon, their presence rose markedly after 1976, when Syrian troops entered the country, where they were to remain for the next 29 years (see First skirmishes). Alawites (whether Lebanese or Syrian) are (relatively) populous in the north of Lebanon, close to the Syrian border.

Politically, Alawites are often close to mainstream Shia and Hezbollah, possibly because they are linked to Syria. This is particularly so among the younger generations. The Alawites were officially recognized as a religious community after Lebanon’s independence. Their religious personal status laws (marriage, divorce, inheritance) were recognized only in the 1990s when they were granted their own representation (two seats) in Parliament. Before that, they fell under the Shiite personal status laws.

Christians

In Lebanon, there are twelve recognized Christian communities. They all have their own personal status laws, and the largest communities are represented in Parliament. The Maronites form by far the largest Christian community in the country.

Persecuted under the Byzantine Empire, the Maronites took refuge in the mountains, as did the Shia and the Druze in more recent times. The three communities generally lived together peacefully – except for some land disputes or rivalries between clans. Today, the Maronites live scattered around the country, with a heavy concentration in Mount Lebanon and Beirut.

Most estimates concerning the size of the community range from 23 to 25 percent of the population. Higher estimates up to 30 percent are probably overrated, if only because emigration was particularly high among young Lebanese Christians during and after the Civil War (1975-1990).

Maronites have traditionally occupied the highest stratum of the social pyramid in Lebanon. For many of their (political) leaders, the Maronite community is the ‘foundation of the Lebanese nation.

The second-largest Christian community is that of the Melkites (Greek Catholics). They live in the same areas as the Maronites. The Greek Orthodox, the third-largest group, is mainly concentrated around Tripoli in northern Lebanon. Also recognized are Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholics, Syrian Orthodox, Syrian Catholics, Chaldean Catholics, Assyrians, Latins (Roman Catholics), Copts, and Protestants.

Jews

Historically, Lebanese Jews formed an integral part of the Lebanese community, even sharing Lebanese Muslims’ names. In the 1960s, the Jews in Lebanon were as many as 22,000, due to the arrival of Jews from Syria and Jordan, who were frightened both by the influx of Palestinian refugees in their countries after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and by the new, official Arab rhetoric and animosity against them.

After the June War of 1967, the Jewish community dwindled as they felt less secure in Lebanon. Today, they number less than 200. Their community is officially recognized as a religious community, although without parliamentary representation.

Palestinian Refugees

While it is estimated that there are about half a million Palestinian refugees on Lebanese territory, the number of Palestinian refugees in Lebanese camps and gatherings did not exceed 174,422 individuals during 2017, according to a census conducted by the Lebanese Central Administration of Statistics and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

Palestinian refugees live in 12 camps and 156 gatherings, distributed over the five Lebanese governorates. The census results showed that about 45 per cent of the refugees reside in the camps, compared with 55 per cent in Palestinian communities and adjacent areas. The majority are concentrated in Sidon (35.8 per cent), followed by the North Region with 25.1 per cent, 14.7 per cent in Tyre, 13.4 per cent in Beirut, 7.1 per cent in Chouf District and 4 per cent in Beqaa.

The results also showed that there are demographic changes in some camps, where non-Palestinians outnumber Palestinians. In Beirut’s Shatila refugee camp, for example, 7.57 per cent of the residents are Syrians, compared to 7.29 per cent Palestinians.

The illiteracy rate among Palestinian refugees is 7.2 per cent, and 93.6 per cent of children aged 3-13 attend school. The unemployment rate is 18.4 per cent, and the increasing unemployment rate among youth aged between 15-19 years currently stands at 7.43 per cent and 5.28 per cent for those aged between 20-29 years.

The number of Palestinian families in camps and gatherings is 52,147, of which 2.7 per cent are Palestinian men married to Lebanese women and 4.2 per cent are Palestinian women married to Lebanese men.

According to UNRWA, the United Nations Palestinian Refugee Agency, the camps suffer from a high level of poverty, overcrowding, unemployment, poor housing conditions and lack of infrastructure. UNRWA puts the number of registered Palestinian refugees at more than 483,000.

Refugee Camps

All but one of the camps are located in the coastal area, around Beirut (Bourj al-Shemali, one of the largest camps; Shatila, which was bombed in 1982; Dbayeh and the tiny Mar Elias), Saida or Sidon (with Ayn al-Hilweh, the largest of all, and Mieh Mieh) and Tyre (Sur) in the south (al-Buss, Rashidieh).

Two camps are close to the north’s Syrian border, near Tripoli (Beddawi and Nahr al-Bared, which is partly closed due to renovations). One camp is located in the Beqaa Valley, Wavel, near Baalbek, was built around old French army barracks.

The largest camp, both in size and number of inhabitants (47,614), is Ayn al-Hilweh near Sidon (Saida). This camp was established in 1948-1949 by the International Committee of the Red Cross to accommodate refugees from northern Palestine.

It grew explosively during the Civil War when other camps were evacuated or even destroyed. The second-largest camp is Rashidieh (27,521 inhabitants), between Tyre and the border with Israel. Close to Rashidieh is Bourj al-Shemali (19,771 inhabitants).

Living conditions

In general, the shelters in the camps are very basic, while living conditions are harsh. Unemployment is extremely high. People find casual work in orchards, on construction sites, as cleaners and (women) in embroidery workshops.

The school dropout rate is high. According to UNRWA, this is because students are often forced to leave school to support their families. Moreover, Palestinian refugees are subject to many employment restrictions, leaving them highly dependent on UNRWA as their main relief provider and a major employer.

In 2005, officially registered Palestinian refugees born in Lebanon were allowed to work in the clerical and administrative sectors for the first time by law. As UNRWA states, however, refugees are still not allowed to practise some professions, such as medicine, dentistry, law, engineering or accountancy.

Violence

Many camps suffered from the violence during the Civil War (1975-1990), which started in 1975 with a clash between armed Palestinians and the (mainly Maronite) Phalange. This violence resulted in many casualties – including the massacres at Sabra and Shatila in 1982 – and the (partial) destruction of the camps, and the displacement of thousands of people.

In some camps, the violence kept resurging as various Palestinian factions continued to clash with one another – or with the Lebanese army. This was the case in the northern camp of Nahr al-Bared, where, in the spring of 2007, heavily armed Salafist Fatah al-Islam shooters took control of the camp before being defeated by the Lebanese military.

Socio-economic Composition

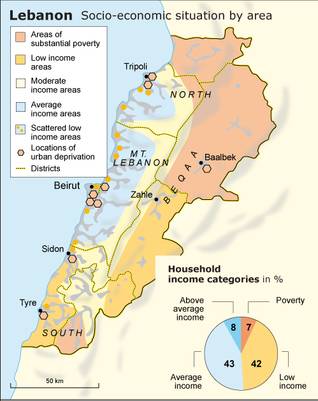

Lebanon used to be called ‘the Switzerland of the Middle East’ because of the importance of its banking system and the relative wealth of its inhabitants. But the economy had since suffered several severe blows, first during the Civil War (1975-1990) and again in 2006, when Israel staged its 33-Day War against Hezbollah.

Moreover, within the population, there are huge differences in income and living standards. Even during the ‘rich’ 1960s, poverty was a problem and a potential danger – some say the Civil War was fought partly for economic reasons. In those days, 33 percent of the national income went to 4 percent of the population, whereas half of the Lebanese population had to share 18 percent of their national income.

Beirut, where most of the economy is concentrated, and the adjoining province called Mount Lebanon – the Maronites’ residence – are among the most prosperous regions. South Lebanon, the Beirut suburbs, and the north-eastern provinces of Akkar and Baalbek, where many Shiites live, are among the poorest.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), one in four were still living below the poverty line in 2004-2005, and 8 percent of the Lebanese population were living in extreme poverty. ‘This implies that almost 300,000 individuals in Lebanon cannot meet their food and non-food basic needs.

There is a huge disparity in the distribution of poverty with a heavy concentration in certain regions. Hermel, Baalbek and Akkar witness the highest poverty rates whereas it goes down to 0.7 percent in Beirut’, it stated. It also meant that Lebanon received financial help to reduce poverty, while some Lebanese made a fortune thanks to the reconstruction programme and low-income taxes.

Income Distribution and Poverty

In 2008, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was 10,880 USD. Literacy, another way of measuring a country’s standard of living, is very high in Lebanon, certainly compared to regional standards. Among the population aged 15 and older, it is 88.3 percent (in 2007), although higher among men (93 percent) than among women and girls (82 percent), according to UNESCO.

These percentages are among the highest of the Middle East, and the youth literacy rate (15-24 years) is even higher (96 percent). According to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report, illiteracy rates are higher among older age groups. Illiteracy is also higher in regions outside Beirut and Mount Lebanon and occurs more frequently among females.

According to UNDP, 8 percent of the Lebanese population lives in extreme poverty (in 2005). ‘This implies that almost 300,000 individuals in Lebanon cannot meet their food and non-food basic needs. There is a huge disparity in the distribution of poverty with a heavy concentration in certain regions.

Hermel, Baalbek and Akkar witness the highest poverty rates, whereas it goes down to 0.7 percent in Beirut,’ the development organization states. The UNDP specifies: while 20.7 percent of Lebanon’s population live in North Lebanon, it is the home of 38 percent of the poor and 46 percent of the extremely poor; this in comparison to Beirut, where only 1 percent of the extremely poor and 2.1 percent of the poor population live.

In its report Millennium Development Goals, Lebanon Report, 2008, UNDP states: ‘In 1998, The Mapping of Living Conditions, that measured poverty using the Unsatisfied Basic Needs approach (UBN), estimated that one-third of the resident Lebanese (34 percent) do not have their basic needs satisfied and were therefore considered to live in poverty.

Of those, 6.6 percent lived in shallow satisfaction conditions and extreme deprivation. To monitor the change in the living conditions of the Lebanese population, ten years after the production of the 1998 Mapping, Comparative Mapping was produced and published in 2007. This study adopted the same methodology, used the same indicators of the 1998 study, and calculated deprivation using the 2004/5 data.

The study showed that the percentage of deprived individuals dropped from 34 percent to 25.5 percent. This decrease was witnessed in all fields (education, housing, access to water, and sewage), except for income-related indicators (employment and economic dependency, and ownership of a car), which showed considerable worsening with an increase in the percentage of deprived households amounting to 8.8 points.’

Poverty and unemployment

The report also shows that poverty continues to be more prevalent among agricultural workers and unskilled workers in services, construction, and industrial sectors, the majority of whom are either illiterate or semi-illiterate. In that respect, the Palestinian refugees living in camps are among the poorest of the poor.

There, unemployment is extremely high, and children frequently drop out of school for various reasons. If they do have jobs, it is generally casual work in construction, agriculture or as cleaners. Child labour still exists among the very poor, whether they are Palestinian or Lebanese. Palestinian refugees are subject to many employment restrictions. (See UNRWA)

On the other hand, unemployment is not only high among unskilled workers. The overall rate is estimated at over 7.9 percent and it is particularly acute amongst the the Lebanese youth, aged 15-24 (48.4 percent of the unemployed), with young women far more adversely affected than young men.

Youth unemployment in Lebanon is estimated to be the same as the average in the Arab region (roughly 26 percent), the highest of all regions worldwide. This has resulted in a growing exodus, particularly among the young (25-45 age bracket), and a serious brain drain, with 25.4 percent of the people holding university degrees emigrating.

(According to the Ministry of Social Affairs, about one in four people aged 15-24 hold a university degree. See National Survey of Households Living Conditions 2004-2005).

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Population’ and ‘Lebanon’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: