Introduction

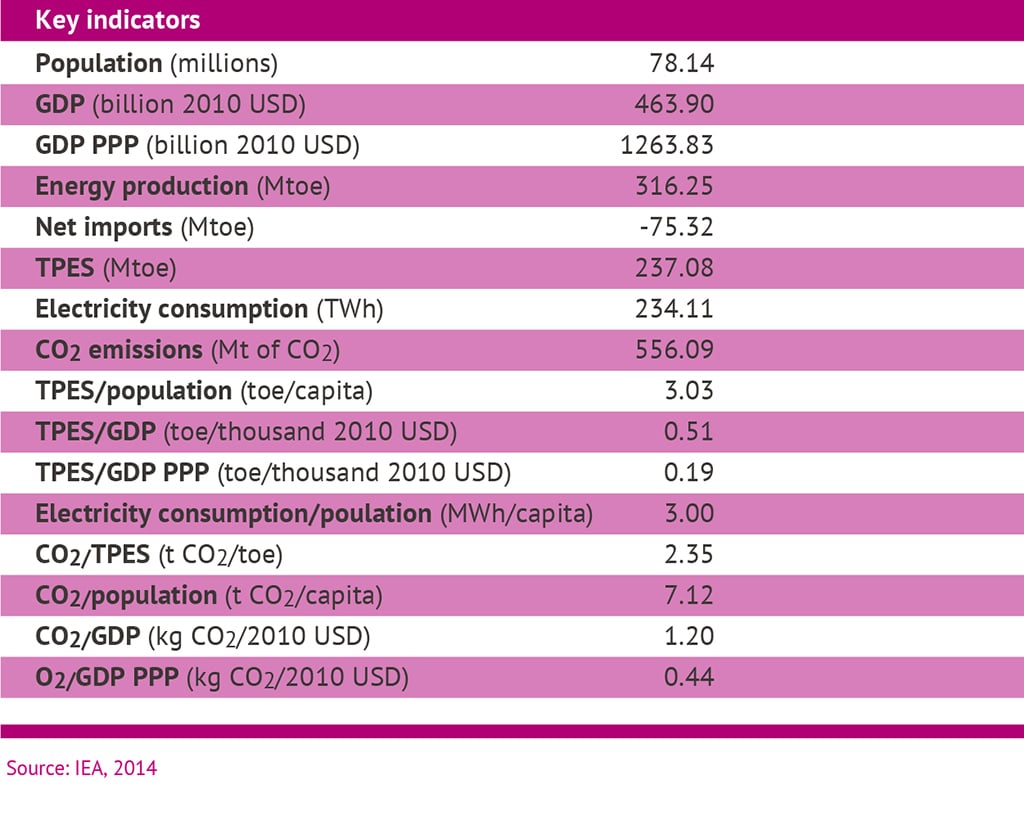

Iran is a massive player in global energy markets, but its present production capacity falls well short of potential. The oil and gas sector remains critical to Iran’s economic prospects. With 10 per cent of the world’s oil reserves, Iran has the fourth largest oil reserves after Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Canada. It has 547 billion barrels (bbbl) of initial oil in place, with almost 160bbbl of it recoverable. In addition, at 18 per cent, Iran has the second-largest natural gas reserves after Russia. Iran is also the second-largest oil-consuming country in the Middle East, after Saudi Arabia. Crude oil is exported via island terminals to tankers that pass through the Strait of Hormuz. There is an extensive domestic network to take the crude to export terminals and refineries. Iran played an important role in the international oil market until sanctions were first imposed in 1979 by the United States in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution and then expanded in 1995 to all business with government. In 2006, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted Resolution 1696, imposing international sanctions designed to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions and activities. In 2012, the European Union (EU) imposed additional sanctions on Iran, halting the vast majority of Iran’s oil exports into Europe including contracts signed before 2012, and banning insurance for Iranian oil shipments [1].

These sanctions have significantly limited Iran’s oil exports and the import of spare parts and equipment. As a result of the war and sanctions, Iranian oil production decreased from its peak of 6 million barrels per day (mb/d) in late 1970 to about 4.2mb/d in early 2000. The nuclear programme-related sanctions further restricted Iranian oil production to below 3mb/d. Despite tremendous potential, Iran’s gas export capacity is relatively trivial and it has no liquefied natural gas (LNG) investments. Since the international nuclear-linked sanctions were lifted in January 2016, Iran has once again emerged as a key player in the global energy markets. Following the nuclear agreement in 2015 with the P5+1 countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, China and France plus Germany), it is expected that many international energy companies will return to Iran’s large oilfields. Iran is currently introducing various reforms and regulatory frameworks aimed at promoting the private sector and liberalizing the market. According to the World Bank’s 2015 projections, Iran’s gross domestic product will grow by 5.1 per cent between 2015-2017 and by 5.5 per cent between 2017-2018.

With about 73 gigawatts (GW) of power capacity, Iran is ranked 14th in the world in terms of installed capacity, 18th in terms of power production and 9th in terms of power exports. Iran’s electricity mix has been traditionally reliant on fossil fuels. As of 2016, natural gas produces almost 92 per cent of the electricity consumed. Since 2005, Iran has seen a growing electricity demand of around 5 per cent annually. This has exposed the country to frequent shortfalls during peak periods. In 2015, Iran had only 12.1 megawatts (MW) of installed capacity of renewable energy. However, it has plans to develop an additional 5,000MW of renewable energy by 2020. The electricity sector has also suffered in recent decades from the international sanctions that prevented any foreign investments or access to new technologies and innovation.

Oil and Gas

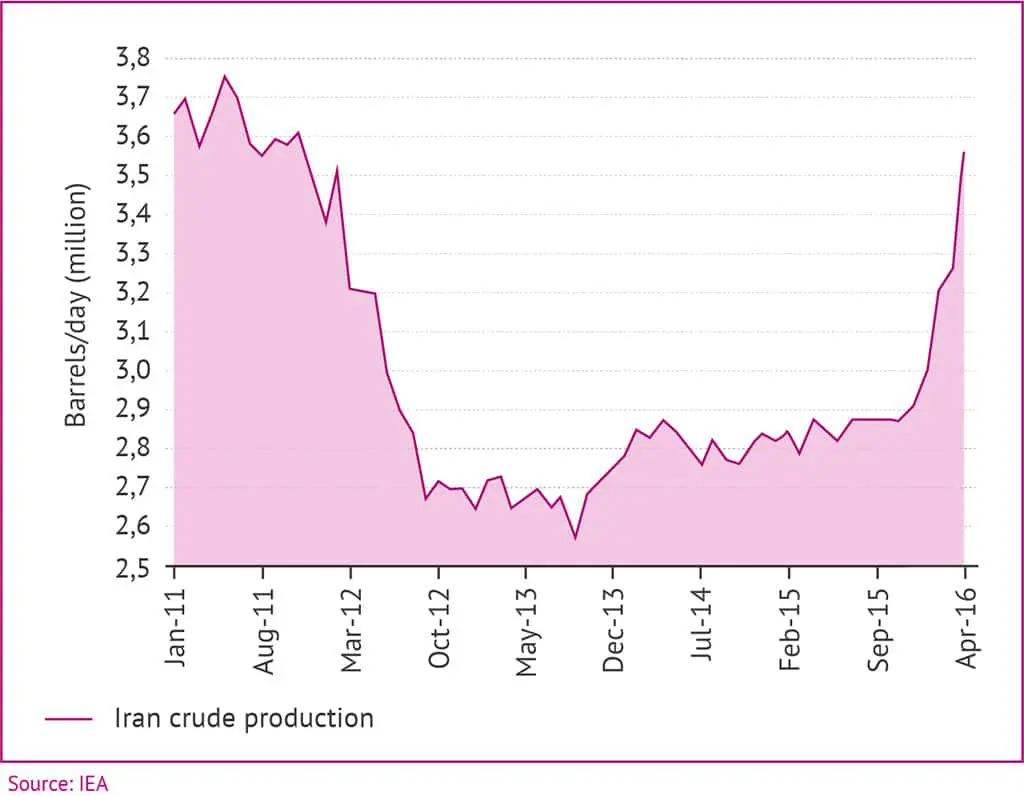

The Iranian oil and gas sector has been through many turbulent decades of revolution, war and international sanctions. The Islamic Revolution and early phase of the Iran-Iraq War resulted in a drop of 3.9mb/d of crude oil production between 1978 and 1981. Much of this lost production was offset initially by increases in output from other OPEC members [2], particularly Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Hostilities between Iran and Iraq finally ended with a ceasefire in August 1988. Iran’s crude oil production, which had peaked at about 6mb/d in 1976, had fallen to 2.3mb/d by the war’s end. As a result of the US, EU and UN sanctions, production fell from an average of 3.7mb/d in 2010 and just over 3.6mb/d in 2011 to an average of 2.68mb/d in 2013. Today, most Iranian oilfields are old and mature and require large investments and efficiency-boosting treatments. Experts suggest that Iran loses an average of between 300-500,000 barrels a day due to the maturity of its fields, equivalent to 8-11 per cent annually.[3]

According to its fifth five-year economic plan for 2011-2016, Iran aimed to increase oil production to 5,152mb/d by attracting $155 billion in investment to its upstream oil and gas sectors. In total, it is estimated that the country’s entire gas and oil industry would need about $300-350 billion in investment to modernize its supply chain both upstream and downstream. Among the key challenges facing Iran in expanding its production and export, is the abundance of global supply and current low crude oil prices of around $50 and the recent decreased quotas at OPEC. Other countries such as Saudi Arabia have secured their market share through long-term agreements. As a result, Iran will face challenges in recovering its market share.

In addition, local demand for oil is growing fast due to governmental subsidies. Iran currently consumes 64 per cent of its oil production. This means it will very likely depend even more on the petrochemical sector (e.g. diesel) to meet local demand while preventing imports of finished oil products in line with its energy independence policy.

In contrast to oil production, Iran’s natural gas production was not affected much during the sanctions period since it relied mostly on local consumption and not export. Although the sanctions did not directly stop Iran from exporting its natural gas, they blocked access to global finance and technologies.

Sector Organization

The energy sector is overseen by the Supreme Energy Council, which was established in July 2001 and is chaired by the president of Iran. The council is composed of the ministers of petroleum, economy, trade, agriculture, and mines and industry, among others. Under the supervision of the Ministry of Petroleum, state-owned companies dominate the activities in the oil and natural gas upstream and downstream sectors, along with Iran’s petrochemical industry. The three key state-owned enterprises are the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), the National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) and the National Petrochemical Company (NPC). The NIOC is responsible for all upstream oil and natural gas projects. The Iranian constitution prohibits foreign or private ownership of natural resources. However, international oil companies (IOCs) can participate in the exploration and development phases through ‘buy-back schemes’. The NIOC, under the supervision of the Ministry of Petroleum, is responsible for all projects encompassing both production and export infrastructure in the oil sector.

The National Iranian South Oil Company (NISOC), a subsidiary of the NIOC, accounts for 80 per cent of oil production in the provinces of Khuzestan, Bushehr, Fars, Kohkiluyeh and Boyer Ahmad. Nominally, the NIOC also controls the refining and domestic distribution networks, by way of another subsidiary, the National Iranian Oil Refining and Distribution Company (NIORDC). The NIGC is in charge of Iran’s natural gas downstream activities, including gas processing plants, pipelines and urban natural gas networks. The NIGC operates through several subsidiaries, including: Iran Gas Engineering and Development Company (IGEDC), Iran Gas Transmission Company (IGTC), Iran Gas Storage Company (IGSC) and Iran Gas Distribution Company (IGDC).

The NIGC holds a trading company, the Iran Gas Commercial Company (IGCC), which sells natural gas plant liquids. Another subsidiary, the National Iranian Gas Exports Company (NIGEC), is in charge of new pipeline and LNG projects. The NPC operates several petrochemical complexes through its subsidiaries. In 2011-12, the NPC accounted for almost 90 per cent of Iran’s total petrochemical production of 46-47 million tons and almost the same share of Iran’s petrochemical exports of 18-19 million tons. The NPC exports petrochemicals through its wholly owned subsidiary Iran Petrochemical Commercial Company (IPCC).

Major Oilfields

Iran’s main oilfields are located near the southern border with Iraq and along the northern part of the Gulf (Khuzestan and Bushehr provinces), including in the shallow waters offshore. According to FGE energy consultants, approximately 70 per cent of Iran’s crude oil reserves are located onshore and the remainder offshore. Roughly 85 per cent of Iran’s onshore reserves are located in the Luristan-Khuzestan basin near the south-western border with Iraq, according to the Arab Oil and Gas Journal.

Iran’s largest onshore oilfields are:

Ahwaz-Asmari (700,000bbl/d)

Marun (520,000bbl/d)

Gachsaran (560,000bbl/d)

Other major onshore fields are:

Agha Jari (200,000bbl/d)

Karanj-Parsi (200,000bbl/d)

Rag-e-Safid (180,000bbl/d)

Bangestan (245,000bbl/d current production, with plans to increase to 550,000bbl/d)

Bibi Hakimeh (130,000bbl/d)

Pazanan (70,000bbl/d)

Offshore capacity includes:

Nowrouz (60,000bbl/d)

Abuzar (175,000bbl/d)

Dorood (130,000bbl/d)

Salman (130,000bbl/d)

Lavan (100,000bbl/d)

Sirri (95,000bbl/d)

Iran also produces crude condensate in the South Pars gas field. Two of Iran’s major untapped fields include:

Azadegan (600,000bbl/d as outlined in contracts)

Yadavaran (300,000bbl/d as outlined in contracts)

The Azadegan field (near the border with Iraq) was Iran’s biggest oil find in 30 years when it was announced in 1999. It contains 6-7bbbl of recoverable crude oil reserves, but its geologic complexity makes extraction difficult and demining and clearing unexploded ordinance is an added cost. Yadavaran is the other major promising new find, with 3.2bbbl of recoverable oil reserves and 2.7 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of recoverable gas reserves. The status of these projects is covered in the next section.

Iran’s crude oil is generally medium in sulphur content and in the 28° to 36° API gravity range. Two crude streams, Iranian Heavy and Iranian Light, account for more than 80 per cent of the country’s crude oil production capacity. The fact that, historically, the country has had little or no real spare capacity is one of the reasons that it has tended to be a ‘price hawk’ in OPEC meetings, pushing for lower rather than higher overall levels of production. Iran’s OPEC quota is 3.36mb/d and it has sometimes had difficulty moving heavy, sour crudes at competitive prices, losing out to the light crudes of its Arab neighbours.

Oil Export Terminals

There are three major oil export terminals in Iran, namely the Kharg, Lavan and Sirri Islands:

Kharg Island : The largest and main export terminal accounts for roughly 90 per cent of Iran’s exports. Kharg’s loading system has a capacity of 5mb/d. The terminal processes all onshore production (the Iranian Heavy and Iranian Light Blends) and offshore production from the Forouzan field (the Forouzan Blend). Its storage capacity was expected to increase to 28mbbl of oil in 2014. Kharg was the focus of attack by Saddam Hussein’s air force in the so-called Tanker Wars during the Iran-Iraq War.

Lavan Island : Bearing the name of the offshore fields, the terminal handles exports of the Lavan Blend (light sweet). Lavan facilities have the capacity to process 200,000bbl/d of crude oil. Lavan has a two-berth jetty, which can accommodate vessels up to 250,000 deadweight tons. Lavan’s storage capacity is 5.5mbbl.

Sirri Island : The Sirri terminal processes crude from the Sirri offshore field complex, and includes a loading platform equipped with four loading arms that can load tankers from 80,000 to 330,000 deadweight tons. Its storage capacity is 4.5mbbl.

In addition to crude oil Iran also exports petroleum products. According to FGE, Iran exported about 240,000bbl/d of petroleum products in 2013, most of which were fuel oil and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) sent to Asian markets. Iran’s petroleum product exports declined by roughly 40 per cent in 2013 compared with 2011, an indication of the adverse effects of sanctions.

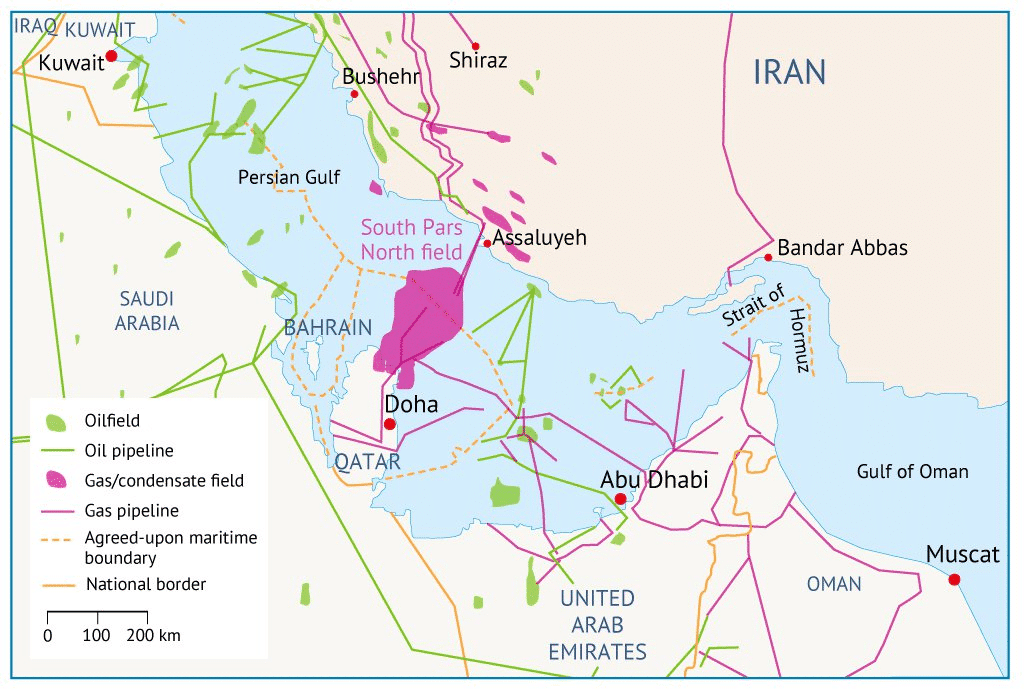

The export terminals Bandar Mahshahr and Abadan (also known as Bandar Imam Khomeini) are near the Abadan refinery (Iran’s second largest) and are used to export refined products from this refinery. Bandar Abbas, located near the northern end of the Strait of Hormuz, is Iran’s main fuel oil export terminal. Condensate from the South Pars natural gas field is exported from the Assaluyeh terminal.

The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most important oil chokepoint because of its oil flow of 17mbbl/d (average in 2013), constituting about 30 per cent of all seaborne-traded oil. The vast majority of Iran’s exports flow through this route. Iran has a hand in controlling the strait, which at its narrowest point is 34km wide. This has led many to be wary of the supply security risks and is likely a prominent factor in the presence of the US 5th fleet in the surrounding water.

Refinery Capacity and Domestic Consumption

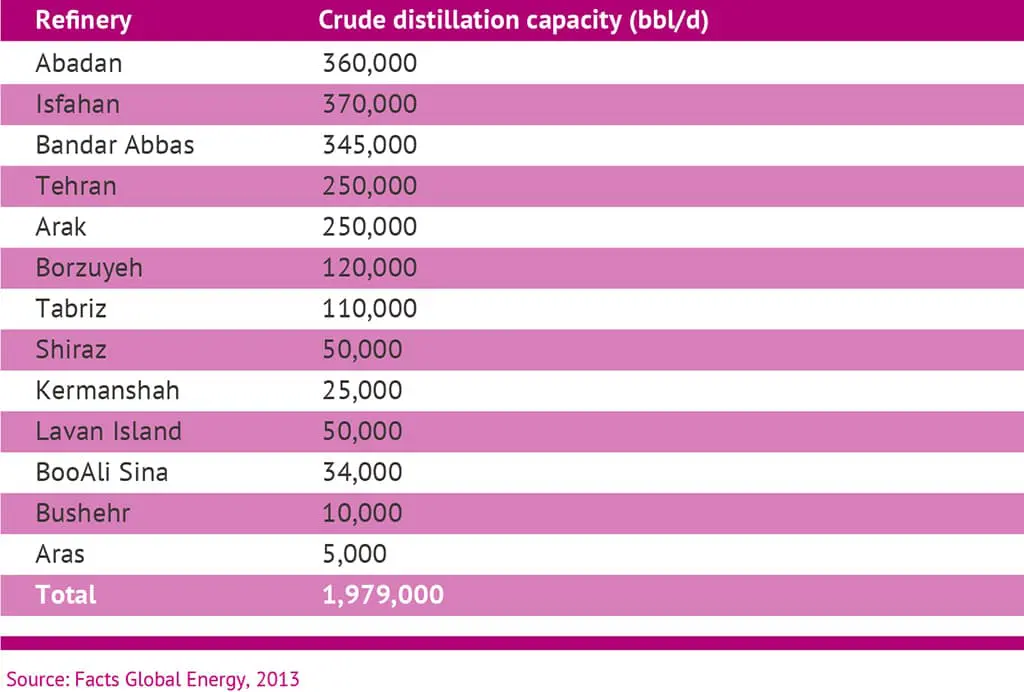

Iranian domestic oil consumption is mainly diesel, gasoline and fuel oil. Total oil consumption averaged approximately 1.75mbbl/d in 2013. As of September 2013, Iran’s total crude oil distillation capacity was nearly 2mbbl/d, about 140,000mbbl/d more than the previous year, according to FGE. Most of that increase came from expansion projects that were recently completed at the Arak and Lavan refineries.

The downstream sector is run by the National Iranian Oil Products Refining and Distribution Company (NIOPRDC). The nine refineries, at Abadan, Arak (Shazand), Bandar Abbas, Isfahan, Kermanshah, Lavan, Shiraz, Tabriz and Tehran, have a combined crude oil throughput capacity of 1.7mbbl/d under optimal conditions. Iran also extracts petroleum products (naphtha and LPG) at natural gas processing plants.

A small amount of crude oil, approximately 4,000bbl/d, is directly burned for power generation. In refinery capacity too, the effects of sanctions have put Iran in the highly perverse position of being one of the world’s largest oil reserve holders on the planet and yet it imports petroleum products. In 2013, FGE estimated that Iran imported almost 17,000bbl/d of petroleum products, of which roughly 85 per cent was gasoline. Over the past several years, however, Iran’s gasoline import dependence has decreased significantly, as a result of increased domestic refining capacity and subsidy cuts. Iran planned to increase gasoline production capacity at the Isfahan and Bandar Abbas refineries by the end of 2014.

Iran’s energy prices, particularly of gasoline, are heavily subsidized. At the end of 2010, the government initiated the first phase of subsidy reform, decreasing subsidies to discourage waste. The second phase of this reform was initiated in early 2014. According to FGE, gasoline prices have risen by 43-75 per cent. As a result, gasoline consumption is expected to decline in the near term, cutting imports.

Large Untapped Gas Resources

Iran has the world’s largest natural gas reserves and is the third-largest natural gas producer behind Russia and the United States. According to Oil & Gas Journal, as of January 2014, Iran’s estimated proven natural gas reserves were 1,201TCF, some 18 per cent of the world’s proven natural gas reserves and more than one third of OPEC’s reserves (about 34 trillion cubic metres). The NIGC operates Iran’s gas fields. The presence of foreign companies has been considerable, particularly in South Pars, although sanctions put much foreign involvement on hold. Iran does not have the infrastructure in place to export or import LNG.

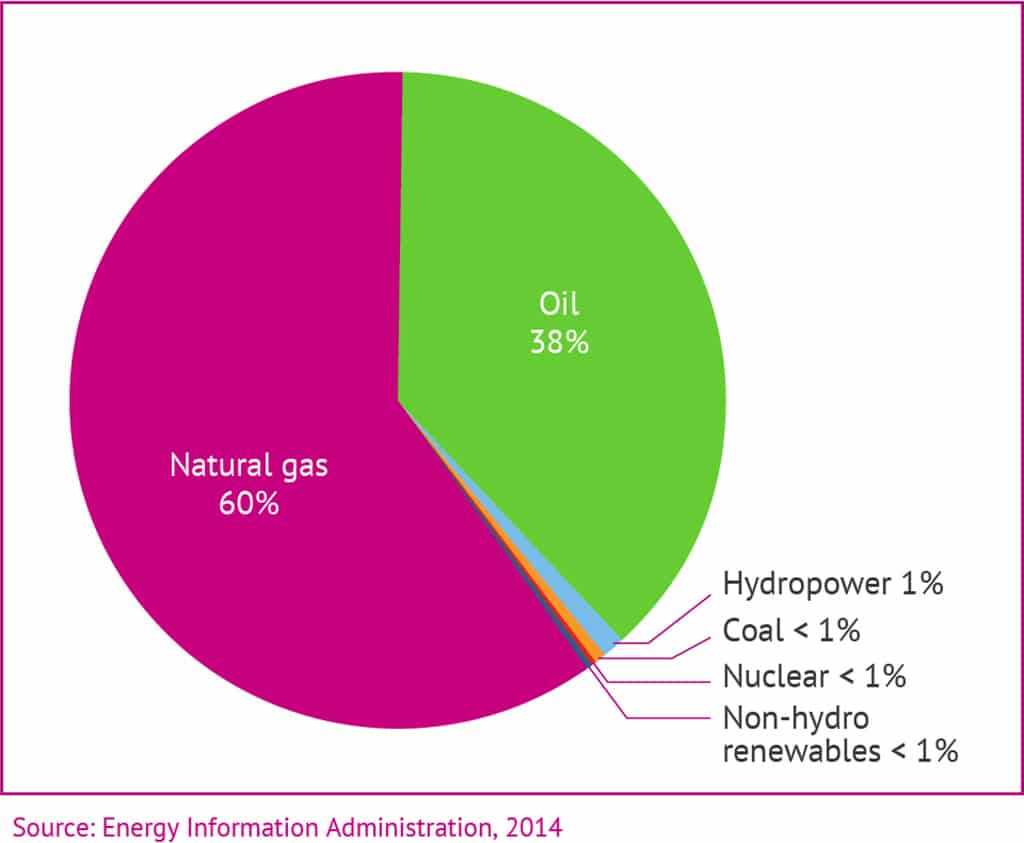

Gross natural gas production totalled almost 8.2TCF in 2012, increasing 3 per cent from the previous year. In 2013, 60 per cent of the total energy consumption came from natural gas. The South Pars field accounted for almost 40 per cent of gross natural gas production. Of the 8.2TCF produced, most of it was marketed (6.54TCF), and the remainder was reinjected into oil wells to enhance oil recovery (1TCF) or vented and flared (0.62TCF). According to Cedigaz, Iran flared the second-largest amount of natural gas in the world in 2012, after Russia. In the same year, Iran exported 326 billion cubic feet (BCF) and imported 188BCF of dry natural gas (net exports of 138BCF), both via pipelines – accounting for less than 1 per cent of global natural gas trade in 2012.

Iran exports natural gas to Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Almost 90 per cent of Iranian exports went to Turkey in 2012. In 2011, Iran received almost 30 per cent of Turkmenistan’s gas exports, but the share dropped to under 15 per cent in 2012 (due to sanctions pressuring financial transactions). Nonetheless, more than 90 per cent of Iran’s natural gas imports still came from Turkmenistan in 2012, and the remainder from Azerbaijan (as Iran exports natural gas to the isolated Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan via the Salmas-Nakhchivan pipeline in exchange for Azerbaijani exports to Iran’s northern provinces via the Astara-Kazi-Magomed pipeline). Discussions are also underway to construct gas pipelines to India and China via Pakistan, and Iran is negotiating new gas export contracts with Oman, Kuwait, Turkey and Iraq.

Despite sanctions, Iran’s natural gas production for local consumption has grown, and output is likely to continue to increase in the coming years. However, that growth will depend on the pace of development of the South Pars field.

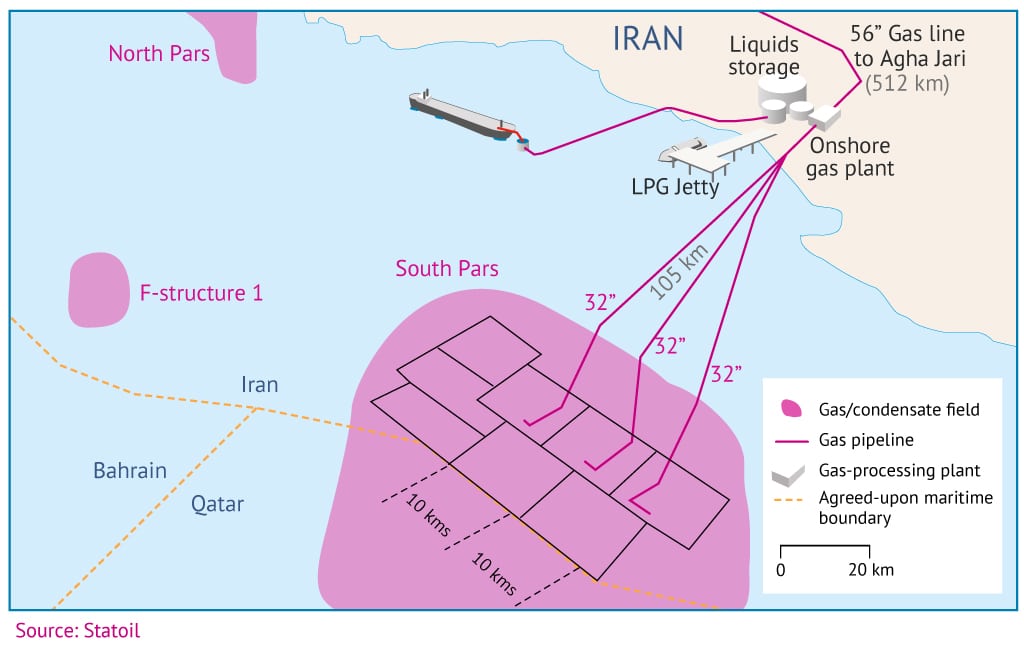

South Pars Gas Field

One of the main reasons for Iran’s enormous reserve figures is that part of the world’s largest natural gas field (shared with Qatar in the Persian Gulf) falls in Iranian waters. This is called the North Field by the Qataris, with the Iranian section called South Pars. About 3,700km2 of the 97,000km2 field are in Iranian waters. Across both sections, the field is estimated to have gas reserves of nearly 51 trillion cubic metres (TCM). The estimates for the Iranian section are 14.2TCM of gas in place and around 10.1TCM of recoverable gas, which accounts for 36 per cent of Iran’s total proven gas reserves.

The Iranian section also holds 18bbbl of condensate (oil) in place, of which some 9bbbl are believed to be recoverable. An issue for Iran in the medium to long term is whether the intensive development of the Qatari sector will hasten the day when South Pars developments begin to see the effects of overall reservoir depletion.

This has already caused tensions between Qatar and Iran. It was also one of the reasons for Qatar to declare a moratorium in 2005 on new projects in the North Field that was expected to last until at least 2015, while reservoir studies were carried out. South Pars, given its size, has a large number of projects (28 ‘phases’), many of which have foreign participation through the buy-back scheme. Iran has been increasingly looking to Asian companies to invest, as political risk and sanctions have deterred Western companies. Overall, the 28 phases are forecast to produce at peak nearly 800 million cubic metres per day (MCM/d). Each phase is producing or planned to produce approximately 40,000bbl/d of condensates, for a total of 1.18mbbl/d.

Gas Fields other than South Pars

Iran has other important natural gas fields besides South Pars, which is only responsible for a minority (36 per cent) of its total proven gas reserves. Most of these fields are located onshore north-east of South Pars, but the three largest fields after South Pars are offshore as well (but wholly in Iranian territorial waters). They are Kish, North Pars and Golshan. Using a conservative estimate, these three fields alone have at least 3.45TCM of proven reserves, with much higher figures for gas in place. Major onshore fields include Nar, Tabnak, Kangan and Khangiran.

Total reserve figures are: Kish (70TCF), North Pars (50TCF), Lavan (66TCF), Golshan (39TCF), Forouz B (25TCF), Ferdowsi (11TCF) and Khayyam (7.3TCF). These fields are currently not producing and many analysts do not expect production until 2020.

Involvement of Foreign Companies

The relationship between Iran and foreign oil companies has historically been complex. In 1940, the Iranian parliament nationalized the Iranian oil industry leading to conflicts with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and a British and American led coup against the government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. AIOC (now British Petroleum/BP) started oil activities in Iran in 1901. Despite a British embargo, Iran succeeded in 1953 in exporting its oil to Italy, Germany and Japan.

Soon after, Iran formed the eight-member consortium called the Iranian Oil Participants (IOP), consisting of BP, Shell, Chevron, Exxon, Gulf, Mobil, Texaco and CFB of France. Although the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) was officially the owner of the Iranian oil deposits and the installed assets, in practice actual control over the industry was in the hands of the companies. This has been one of the key reasons for Iran to work on boosting its logistical capacities to transport its own oil to the global markets by establishing the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC).

Soon after the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, Iran’s revolutionary government expelled foreign oil concerns and NIOC appropriated their assets and cancelled all contracts. Iran’s ban on foreign investment in the oil sector until 1998, and the almost-constant pressure of sanctions following the hostage crisis at the US embassy in Tehran, served to inhibit growth. Despite seeming breakthroughs with regard to engagement with the outside world and hence with foreign energy companies, the theocratic regime, whose position was solidified during the war, is again under strict sanction for alleged attempts to build a nuclear weapon. This has upset the regional balance of power and the global security situation at large.

During the Iran-Iraq War, the oil industry in many border areas was damaged (particularly those installations located in Khuzestan province), and Iran struggled to obtain replacement parts for US-made equipment. Additionally, Iran’s export terminals suffered. The so-called Tanker War started when oil terminals and oil tankers were attacked by both Iran and Iraq.

Lloyd’s of London, a British insurance provider, estimated that the Tanker War damaged 546 commercial vessels from various countries and killed about 430 civilian sailors. After the war, the NIOC made new investments and repairs in an effort to restore production levels and regain the country’s position as OPEC’s second-largest producer. The company was able to increase crude oil production substantially, but levels still fell well short of the high reached in the 1970s. By the mid-1990s, production hovered at around 3.6mbbl/d.

In 1997, President Mohammad Khatami’s government recognized that foreign investment could help increase production and assist with the development of the natural gas sector. However, because the post-revolution constitution prohibits foreign concessions (or any foreign or private ownership of natural resources, and all production-sharing agreements – PSAs – are prohibited), a special type of investment vehicle was created called a ‘buy-back scheme’. The buy-back scheme can be defined as a risk service contract, under which the contractor is paid back by being allocated a portion of oil or gas produced as a result of providing services [4]. Hence, there is no formal share in the oil or gas field. Under these terms, over $40 billion was invested in the hydrocarbons sector between 1997 and 2004.

The amount of investment and technology transfer that came in when some of the top European majors and independents made investments in this period was, however, limited in scope, concentrated as it was largely in the South Pars gas and condensate projects. Since the mid-2000s, this foreign investment, particularly by US and European companies, has been curtailed, as companies are worried they will run into problems with the US government. More recently, certain US, EU and United Nations Security Council sanctions have come into effect. Moreover, risk perceptions of Iran have increased, and the buy-back scheme has not always been globally competitive despite a modification in 2007 to make it more financially attractive.

The implications of sanctions for foreign operations are significant and directly affect the technological capabilities that can be brought to bear on Iranian fields. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recent Medium-Term Oil Market Report, US and EU sanctions had an immediate market impact on crude exports, but they are also putting a stranglehold on Iran’s oil production capacity in the medium term.

The NIOC’s finances have been severely strained, limiting the company’s ability to fund even routine field maintenance work, infrastructure repairs and planned projects. Under-investment in exploration and production and the unavailability (in part due to sanctions) of the latest enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques (standard on large fields in most places in the world) may mean that decline rates are set to accelerate. Information on Iran’s oilfields is very limited given the lack of foreign participants in the sector, but estimates for field decline rates range from 8-12 per cent in the last decade. More than half of Iran’s crude oil production is from fields discovered more than 70 years ago that are costly to operate in later stages. Iran started producing crude oil in significant quantities from Agha Jari and Gachsaran in the late 1940s, and these and other old fields are in desperate need of EOR methods and rehabilitation with new technology.

The pressure applied by sanctions has in turn seen the Oil Ministry increase pressure on the few foreign companies still operating in the country. The only remaining major foreign partners, CNPC (China’s national oil company) and Sinopec, also Chinese, are under increasing pressure to fast track stalled projects designed to increase capacity. The Oil Ministry cancelled CNPC’s contract for the massive 600 thousand barrels per day (kbbl/d) South Azadegan project in April 2014.

CNPC signed the $2.5 billion contract three years ago and planned to develop the field in two parts, with phase one scheduled to bring on 320kbbl/d by mid-2014 and phase two scheduled to bring on 280kbbl/d by 2017. To date, only seven of around 160 planned wells have been drilled. CNPC retains its contract to develop the North Azadegan project, however. Phase one is underway and expected to be completed by 2015-16 (75,000bbl/d). Phase two is expected to be completed by 2020 (75,000bbl/d).

These are dramatically smaller volumes than those planned for the southern portion of the field. Sinopec is also falling behind at the Yadavaran field, with only limited progress despite an initial planned 2012 start-up. Sinopec, along with an NIOC subsidiary, was awarded the contract for the 300kbbl/d project. In 2015, production was just 25kbbl/d versus the plan to have output at 85kbbl/d by 2012. There is no timeline to increase output further, which could likely lead to the cancellation of Sinopec’s contract. The Chinese companies report that sanctions have caused chronic delays in bringing much-needed equipment and technology into the country, with payment issues being another major problem.

Increasing domestic needs and declining exports due to these needs indicate fewer funds available for investment. The NIOC claims that each barrel of new crude oil capacity costs between $7,000 and $7,500 to develop, but many analysts believe that the true figure is significantly higher. Bringing online the large new discoveries, particularly the important Azadegan (5.2 billion recoverable barrels) and Yadavaran (3 billion recoverable barrels) fields, will remain costly.

Planned expansion of capacity at existing fields also continues to be delayed by lack of technology and equipment. Development at the offshore Forouzan field was postponed again, to late 2014 at the earliest. At 60kbbl/d of capacity, Forouzan was initially slated to be on stream in 2008. The NIOC pushed back the date, with only small incremental volumes expected to start by late 2014. Smaller developments such as the 35kbbl/d South Pars (condensate layer) were also pushed back from 2013 to the first quarter of 2015.

Following the nuclear agreement in 2015 with the P5+1 countries, it is expected that many international energy companies will return to Iran’s large oil and gas fields. However, low crude oil prices of around $50 is putting pressure on the profitability of those firms which have already lost their production profitability in many fields. The investment plans that were based on high oil prices were dropped. Still, since the average costs of oil production in Iran range between $5-10 per barrel, this is a key driver for foreign companies to invest in Iran. Foreign companies will continue returning to Iran, however, while watching carefully the signals they receive from their national governments regarding the implementation of the Iran nuclear deal.

Currently, phases one through ten are producing. Phases two and three (part of the same development contract) are producing above target, at a combined 79MCM/d. Gas from phases six through eight is used in large part for injection in the Agha Jari oilfield. Many of the future phases are planned to be part of LNG export schemes or even piped gas exports to Turkey. Total (France) of phases two and three, Eni (Italy) of phases four and five, and Statoil (Norway) of phases six through eight have suspended operations in South Pars.

Most of the rest of the companies are Iranian, though some South Korean companies were involved in the construction of phases nine and ten, and Petronas (Malaysia) and Gazprom (Russia) are active in phases one, two and three. In response to the exodus of Western companies, Iran has looked toward Eastern firms, such as state-owned Oil Corp (India), Sinopec and Gazprom, to take a greater role in Iranian natural gas upstream development. However, activity from these sources has also been on the decline because of pervasive sanctions imposed on technology and financial transactions.

Another important aspect of Iran’s export strategy is the development of LNG export capability. Currently, Iran is meeting with European companies to advance its LNG plans and most likely to acquire a floating LNG platform, which would enable LNG exports of around 1.5BCM/year.

Electricity

In 2015, the installed capacity of Iran’s power plant reached 73,000MW, of which about 45 per cent is privately owned. The peak load is 50,178MW. Today, natural gas and oil make up 92 per cent of the electricity consumed in Iran. Hydropower, nuclear and non-hydro renewables make up the other fuel sources for electricity generation. In total, renewable energy in 2015 made up only 0.2 per cent of the electricity mix, or 12.1MW. Iran has witnessed an average of 5 per cent growth in electricity demand since 2005. As of 2013, the main end-users are the industrial sector (38.1 per cent) and the residential sector (32.2 per cent).

Iran benefits tremendously from electricity exports. Currently, it exports power to Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nakhchivan and Armenia. It also has reciprocal agreements with Turkmenistan, Armenia and Azerbaijan. In 2015, Iran, through its Export Development Fund, announced plans to invest $91 million to construct a third interconnection line with Armenia, boosting capacity to 1GW.

In addition, talks are underway with Pakistan to purchase 1GW. In 2014, Iran exported a total of 9.956 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity and imported 3.769TWh. To boost exports following the nuclear deals, Iran aims to add around 1GW of new capacity each year.

Sector Organization

Electricity wholesale in Iran is carried out at: 1) the Power Market of Iran of the Iran Grid Management (IGMC), under the regulatory supervision of Iran Adjusting Power Market Association of the Ministry of Energy; and 2) the Iran Energy Exchange (IRENEX). Under the Ministry of Energy, the two state-owned companies that run the sector and operate most of the power plants are the Iran Power Generation Transmission & Distribution Co. (Tavanir) and Tehran Regional Electricity Co. (TREC).

As of 2014, Iran’s transmission network included 132 kilovolts (kV), 230kV and 400kV power lines covering 73,279km, combined with a transformer capacity of 153,746 megavolt amps (MVA) [5]. Currently, Tanavir is responsible for the management of 16 regional electric companies, 32 generation management companies, 42 distribution companies, Iran Power Development Companies (IPDC), Iran Organization Renewable Energy (SUNA), Iran Energy Efficiency Organization (SABA), Iran Power Plant Project Management (MAPNA) and Iran Power Plant Repairs Company.

Whereas the sector is mostly government owned, 60 per cent of distribution grids are owned by private entities that are responsible for their development, operation and maintenance. This is part of larger privatization efforts in the power sector. In 2011-2013, at least 38 power plants with a total installed capacity of 29,000MW were transferred to the private sector. Additional privatizations will occur between 2016-2020. Furthermore, the government plans to reduce the subsidies to the power sector, as it did in 2014 by 20 per cent and again in 2015 by another 25 per cent. Iran is confronted with an average of 19 per cent grid loses.

Nuclear and Coal Energy

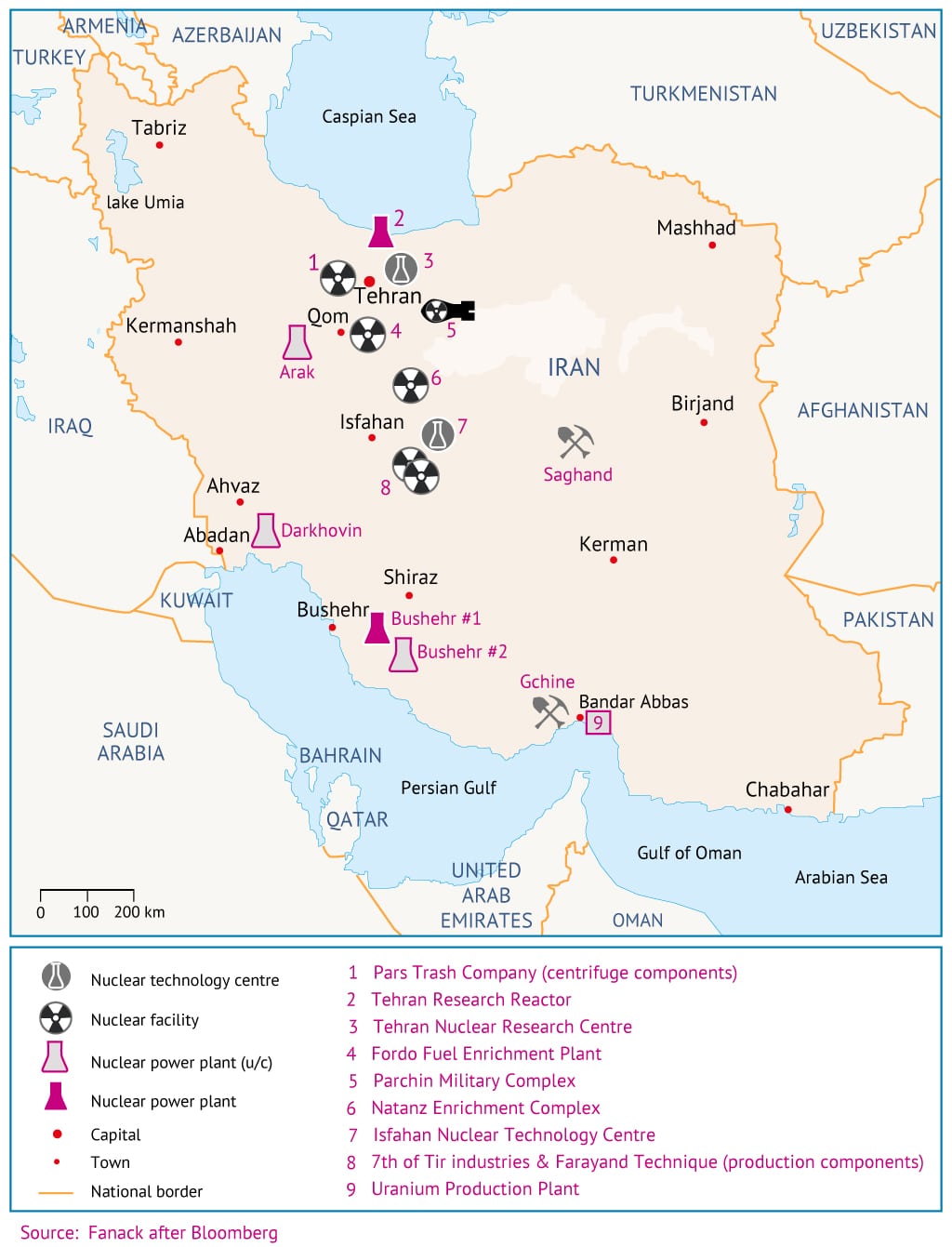

Iran’s ambition is for nuclear energy to play an important role in its energy mix. Its first nuclear power plant at Bushehr became operational in 2011, but did not start commercial production until 2013. Construction at the plant originally began in the mid-1970s but was repeatedly delayed by the Islamic Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War and more recently by problems associated with the Russian consortium that was awarded the construction contract. The Iranian government took control of the management of the plant in late 2013, around the same time the plant began commercially producing power at its full capacity of 1,000MW, according to BMI.

Two additional units are planned at Bushehr (see Map 5), each with a planned capacity of 1,000MW, according to the World Nuclear Association, as well as a station likely to be near Darkhovin, with a generation capacity of 360MW, although initial plans included capacity of more than 1,000MW. Iran, along with the United Arab Emirates, is the only other MENA country with concrete plans to develop power generation capacity from nuclear fuel. Between 2016-2024, Iran’s power generation is expected to rise by an average of around 3 per cent annually, to 325,3TWh. In the same period, local power consumption is expected to increase to 276.43TWh, an annual increase of 3.11 per cent.

Iran has a relatively small but significant coal mining industry. This is in contrast to the other countries in the region which have no coal mining industries, except for a very small one in Egypt and a relatively large sector in Turkey (see Country Report: Turkey). It is estimated that Iran produced about 1.7 million tons of coal in the most recent Iranian year. There are three large concerns that produce the overwhelming majority of the country’s coal: Kerman Coal Mines Company, Eastern Alborz Coal Mines Company and the Central Alborz Coal Company. Most of the coal is used for industrial/metallurgical purposes, though a coal-fired power plant is under construction.

Renewable Energy

The high level of energy consumption and CO2 emissions, combined with costly electricity production, are the key drivers for the adoption of policies aimed at increasing the share of renewable energy by 5GW by 2020 and to increase the share of solar and wind by 10 per cent by 2024. To meet these targets, Iran has introduced laws guaranteeing power purchase for a period of 20 years at competitive prices ranging from 2,900-4,873 Iranian rials/kWh, depending on the renewable energy technology applied. These plans would need the investment of at least $4.4 billion.

With an area of 1,648,195m2 and various climates of mountains, lakes, rivers and desert, Iran has a wide variety of natural environments. It enjoys tremendous direct normal irradiation (DNI) of 5.5kWh/sqm/day and an average of 300 sunny days per year. This is especially the case in the central and southern regions, such as the provinces of Yazd, Fars and Kerman, which have DNI of about 5.2 to 5.4kWh/sqm/day. Current installed solar capacity is only 0.51MW. A further 10MW are under construction. SUNA plans to install 500MW by 2020.

Iran also has the potential to install 100GW of wind energy. Currently, 15 wind farms produce only 54MW of installed wind energy. Negotiations are underway with German and Danish companies, which have already signed off a 48MW wind farm project assessed at about $46 million. In addition, Iran has 10MW of biomass and 0.44 of installed small hydro capacity.

Energy Sector in the Face of the Nuclear Programme

Why the sanctions?

Iran is a signatory to the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, but there is international concern about its uranium enrichment programme, which may be diverted away from its ostensible civilian purposes to build a nuclear bomb. Iran has cleared the biggest hurdle to creating a nuclear bomb in learning to make the fissile material that fuels the massive blast. At Iranian facilities, centrifuges spin at supersonic speeds to separate the explosive uranium-235 isotope from uranium ore (see Map 5). The machines refine the metal to low enrichment levels to make fuel for nuclear power plants, but they could be modified to make higher grade material for bombs.

As a consequence, in 2006, the United States Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 1696 and imposed sanctions after Iran resumed its enrichment programme. The UNSC has adopted six resolutions since 2006, requiring Iran to stop enriching uranium and cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Sceptics were not satisfied by IAEA verification, however. They pointed to the example of Iran’s two main uranium enrichment plants – a hardened bunker in Natanz and a mountainside chamber in Fordow – that Iran acknowledged only after they were exposed by an Iranian opposition group outside the country (see Map 5). In response, the IAEA sought more extensive inspections.

The US and EU imposed their own sanctions on Iranian oil exports and banks. The EU imposed restrictions on trade and equipment which could be used for uranium enrichment, and froze the assets of individuals and organizations that it believed were helping to advance the country’s nuclear ambitions.

It also banned the individuals from entering EU member states. In January 2012, the EU additionally froze assets belonging to the Central Bank of Iran and banned all trade in gold and other precious metals with the bank and other public bodies. Six months later, an EU ban on the import, purchase and transport of Iranian crude oil came into force. The 27 member states had until then accounted for about 20 per cent of Iran’s oil exports. European companies were also prevented from insuring Iranian oil shipments, having previously underwritten 90 per cent of them. In March 2012, SWIFT, the Brussels-based body that handles global banking transactions, cut Iranian banks from its system, making it almost impossible for money to flow in and out of Iran via official channels. In October 2012, the EU banned any transactions with Iranian banks and financial institutions, as well as the import, purchase and transportation of natural gas from Iran, the construction of oil tankers for Iran, and the flagging and classification of Iranian tankers and cargo vessels. In February 2012, the US froze all property of the Central Bank of Iran and other Iranian financial institutions as well as that of the Iranian government within the United States.

The US’s view was that sanctions should target Iran’s energy sector, which generates about 80 per cent of government revenues, and try to isolate Iran from the international financial system. Additional sanctions implemented in February 2013 effectively barred Iran from repatriating earnings from its oil exports, depriving Tehran of much-needed hard currency. As with all other sanctions, countries that violated the new requirements risked being expelled from the US financial system, among other penalties.

Iran repeatedly questioned the legal basis of demands to suspend work, and before it made any concessions it wanted what it calls its ‘right’ to enrich uranium recognized, noting that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty does not ban such enrichment. However, evidence that the heavy sanctions were taking a toll became apparent in November 2013, when world powers agreed to a temporary accord setting limits on Iran’s nuclear programme – while in fact accepting its enrichment programme – in exchange for about $7 billion in sanctions relief. On 14 July 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was concluded between Iran and the five permanent members of the UNSC (United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia and China plus Germany, the P5+1.

What does the JCPOA says?

The JCPOA aims to reach a long-term comprehensive agreement that ensures that Iran’s nuclear programme is peaceful, in return for the lifting of international sanctions. The JCPOA is a complex document, detailing strict timelines and milestones for each side and a clear dispute settlement mechanism.

The key points on Iran’s nuclear ambitions are:

Iran must give up two thirds of its ability to enrich uranium. This is considered the vital process that could be applied to generate the core of a nuclear bomb. 13,500 centrifuges will be stored and monitored by the IAEA. Iran is allowed to use only 6,000 centrifuges.

Iran is required to export almost all of its eight tons of low-enriched uranium, keeping only 300kg.

The combined effect of these actions is to be able to extend the period Iran would need to have enough highly enriched uranium to build one nuclear bomb to 12 months. On the day the agreement was signed, Iran was about three to four months away from reaching this target, if it indeed decided to acquire a nuclear weapon.

Iran must convert the Fordow enrichment plant into a research centre. This plant was built in secret inside a mountain. About two thirds of the centrifuges in Fordow have been dismantled and the other 1,000 will not be utilized for the enrichment of uranium.

The Arak heavy water plant will have to change its purpose and is undergoing a redesign and restructure that will make it impossible to produce weapons-grade plutonium.

Iran is obliged to implement the Additional Protocol of the IAEA’s safeguards agreement, which grants IAEA inspectors more powers to monitor all nuclear plants and other facilities in Iran.

In return for Iran’s actions, the international community must recognize the right of Iran to enrich uranium designed for peaceful purposes, in accordance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Only once the IAEA has concluded that Iran has implemented its part of the agreement will all nuclear-related economic sanctions imposed on Iran be lifted (‘Implementation Day’). This includes oil embargos and financial restrictions, which implies the release of about $100 billion of frozen Iranian assets. Furthermore, on Implementation Day, the JCPOA states that the US and the EU will provide sanctions relief that goes beyond the scope of the interim JPOA, signed in November 2013 to encourage negotiations, among others, in the energy sector. As anticipated in the agreement, the IAEA announced on 16 January 2016 that Iran had taken the necessary preparatory steps to mark Implementation Day. In line with this announcement, the US and the EU confirmed the relief of the sanctions under the JCPOA.

US sanctions relief distinguishes between US persons and non-US persons. According to the US, the JCPOA relates to US persons when it comes to the lifting of secondary sanctions on specific transactions related to commercial aircraft sales to Iran and the import of Iranian foodstuffs and carpets. All other sanctions relief relates to non-US persons. Thus, US citizens and entities will remain prohibited from doing any business with Iran, whether direct or indirect. In addition, Iran will still be subject to an UN arms embargo for a further five years, till 2020. The embargo will apply to Iran’s ballistic missile programme for another eight years, till 2023.

In addition, the US has removed most Iranian financial institutions and other entities from the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s Specially Designated Nationals (SDN), Foreign Sanctions Evaders (FSE), and Non-SDN Sanctions Act lists.

Implications for the Energy Sector

From an American perspective, non-US companies or persons are no longer prohibited from conducting the following energy-related activities:

Investing in the energy sector;

Exporting oil products, natural gas and all related services from Iran;

Providing products and services in support of the Iranian energy sector;

Carrying out transactions with, or on behalf of, Iranian financial institutions that are no longer on the SDN list;

Carrying out transactions with Iran’s port sectors including shipping and shipbuilding;

Providing insurance, reinsurance or services in connection with Iran’s shipping and energy sectors.

As a consequence of the lifting of the EU sanctions, the import, purchase, swap and transport of oil products, natural gas and petrochemical products from Iran is now fully permitted. This also implies that any EU person is free to export the related equipment or technology, and provide technical assistance, used along the value chain in the Iranian energy sector. The EU also removed the sanctions on oil and gas-related investments including finance in and outside Iran by Iranian persons. This was combined with the removal of the restrictions on finance, banking and insurance. Thus, the transfer of funds between EU persons, entities or bodies and non-listed Iranian persons, entities or bodies is permitted, without the previously required authorization and notification of such a transfer. Non-listed Iranian banks are now allowed to operate in the EU by establishing branches and subsidiaries, engaging in joint ventures and/or opening offices.

Sanctions related to SWIFT codes, guarantees, expert credit and insurance were also lifted, opening up these facilities to Iranian persons and the Central Bank of Iran. This includes the possibilities of financial assistance and concessional loans to the Iranian government. Furthermore, the EU has listed a number of activities related to shipping and transport that are no longer prohibited. This includes, among others, sales or supply of naval technologies for shipbuilding, including the maintenance, design and construction of cargo ships, oil tankers and other vessels designed for the transport or storage of oil and gas products. In addition, cargo planes have been granted access to EU airports and are thus no longer subject to seizure in the EU, and the travel ban imposed on some, although not all, Iranian persons and entities, has been lifted.

Regardless of the JCPOA, however, certain EU sanctions that impact Iran’s energy sector remain in place. The most important are nuclear-related transfer and activities, including the provision of software and metal designed for nuclear use. These activities require prior EU authorization.

Both the US and EU sanctions are linked to full execution of the JCPOA. This means that in the event that Iran does not implement the agreement as stipulated, the sanctions will be re-imposed pursuant to the so-called ‘snapback’ provision. Lifting the US nuclear-related sanctions will make it significantly easier for non-US companies to do business in Iran and restore Iran’s access to the international financial system and certainly enable it to export oil products. Some of the remaining US sanctions, and especially those with extraterritorial application, will very likely continue to affect any Iran-related business worldwide.

[1] For the complete overview of EU-Iran trade relations, see https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/iran/.

[2] At the time, the other countries besides Iran were Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, which had founded the cartel in 1960. These countries were later joined by Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973) and Gabon (1975).

[3] Vakshouri, S. (2015). Iran’s Energy Policy After the Nuclear Deal. Atlantic Council, Global Energy Center.

[4] Buy-back is based upon a defined scope of work, a capital cost ceiling, a fixed remuneration fee and a defined cost-recovery period. When buy-back is used for both exploration and development, the specifications of the field to be developed are unknown at the time of contracting and therefore agreement on the scope of work, duration of development operations, ceiling for capital costs, fixed remuneration fee and duration of cost recovery need to be deferred to the time when a commercial field is discovered.

[5] See www.globaltransmission.info.