Introduction

Bahrain’s population was around 1.57 million at the end of 2023. Bahrainis made up 46.1% of the population while Non-Bahrainis accounted for the remaining 53.9%. According to UN Data, Algeria’s gender ratio in 2023 is approximately 164 men per 100 women.

The data shows that the number of foreign residents is continuing to grow.

In 2017 alone, more than 64,000 foreigners arrived in the country, an increase of 8.4 per cent, compared to only 12,000 Bahrainis, an increase of 1.8 per cent.

Overall, the population growth rate was 2.36% between 2022 and 2023, up from 2.11% between 2021 and 2022.

According to official figures, the percentage of Bahrainis in the total population decreased from 50.1% in 2007 to 46.1% in 2023. The increase in non-citizens and the continued flow of migrant labour into the country raises questions about the demographic structure and its impact on Gulf identity.

Muslims represent 80.6% of the population with the majority of the Shiite sect, Christians 12.07%, others (Hindus, Buddhists, and other religions or not affiliated with any religion) 7.33% ( 2023 estimates).

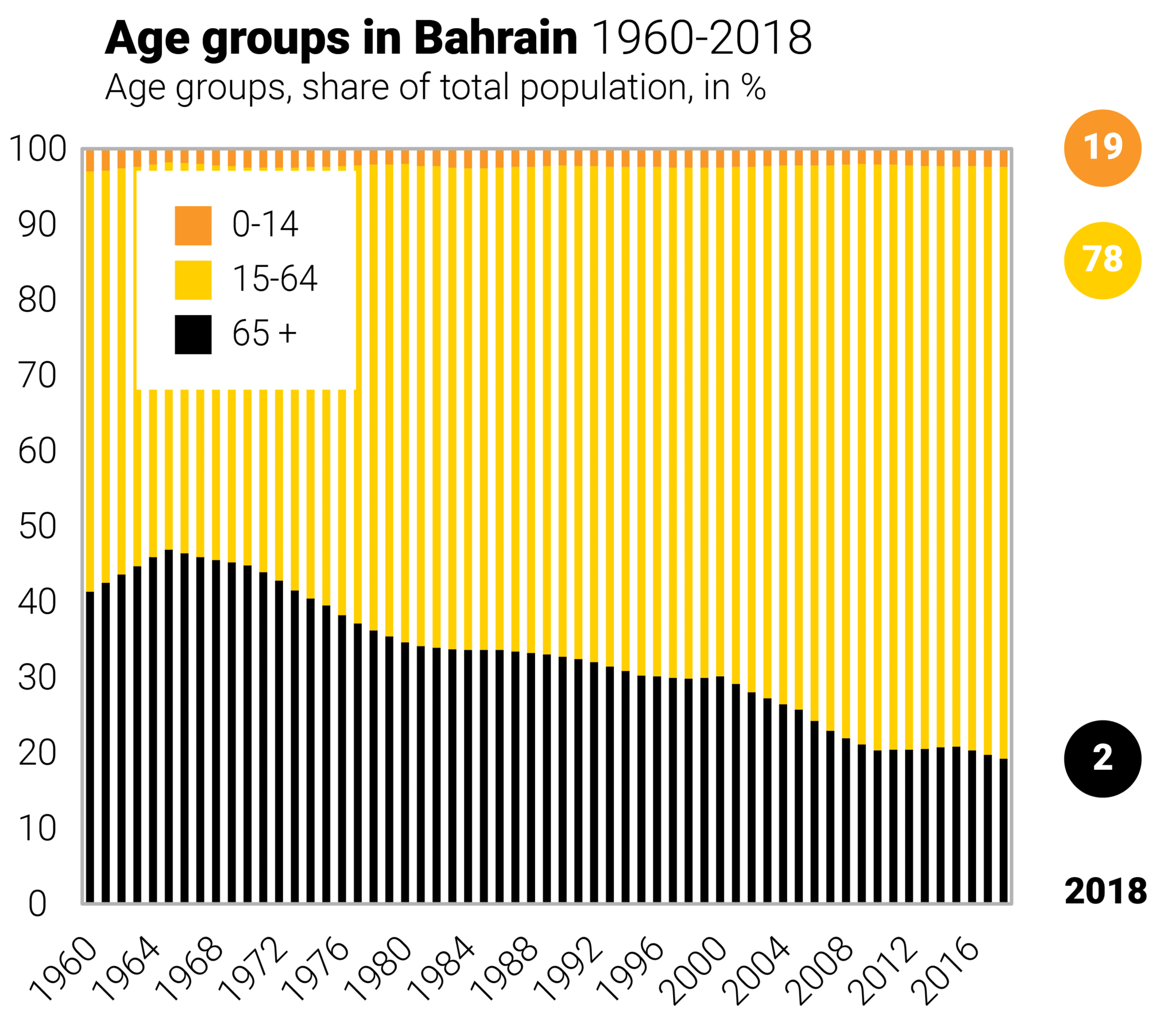

Age Groups

The age structure of Bahrain’s population is relatively balanced. Around 90% of the population are under the age of 55, according to 2023 estimates. Of these, 19% are under the age of 15, 12.2% are aged 15-24 and 58.4% are between 25 and 54 years old. Only 3.6 per cent are 65 and over.

In 2023, the fertility rate is 1.82 births per woman, and the average life expectancy for Bahrainis at birth was 81.28 years (80.67 years for men and 81.99 years for women).

Population Distribution

In 2023, an estimated 89.9 per cent of the population lived in urban areas. With an area of just 786.8 km2, the country is densely populated, with 2,005 people/km2 in 2023, compared to 1,894 people/km2 in 2020.

According to 2023 estimates, the capital Manama accounts for 45.6 per cent of the total population, followed by Muharraq with 18.4 per cent. The rest of the population is distributed across the northern and southern governorates.

Ethnic and Religious Groups

Bahrain is a small country, where most indigenous family names are part of the collective memory of society. Bahrainis can usually identify a family’s historical national origins, religion, and social status from the name alone. The ruling family has used this knowledge to co-opt rival claimants to power, distribute favours and jobs among loyal groups, and repress and exclude the disloyal or unruly.

Sunnis

One of the most important divisions in Bahrain is between Islamic groups, with Sunnis generally enjoying more wealth and power than Shiites. At the top of the pyramid, where most of the nation’s wealth and power is concentrated, stands the ruling family: the Al Khalifa, descendants of Sheikh Isa bin Ali, who ruled from 1869 to 1923. These Banu Isa (‘offspring of Isa’) have ruled Bahrain since the early 20th century. Their leading position has both a political and a commercial basis. In the late 18th century the Al Khalifa began to confiscate much of the agricultural land and other property belonging to the archipelago’s original, mostly Shiite, inhabitants. The agricultural lands were redistributed as private estates among prominent family members and some allied Sunni tribes. After the creation of a modern bureaucratic state based on oil revenues, the Al Khalifa landholders amassed fortunes through the commercial development of these estates. As the state bureaucracy grew, some used their positions in the administration for personal gain.

The Al Khalifa adhere to the Maliki school of Sunni Islamic law. They trace their origins, through the Bani Utba or Utub (who today rule Kuwait), to the Anizza tribe of central Arabia. Not all loyal tribal Arab groups are Bani Utba/Utub, but they all came to Bahrain around the time of the Utub invasion. Historically, the Al Khalifa relied on the fighting power of these tribes and intermarried with them. As in all Gulf monarchies, however, the status of the tribes has declined vis-à-vis the ruling family since the rise of oil and a modern bureaucratic state. Following the arrival of oil revenues and the emergence of professional security forces, ruling-family endogamy has increased. Members of tribes loyal to the Al Khalifa are today employed in the state bureaucracy and in the armed forces

Today, the ruling family’s traditional urban allies are much more powerful than their Sunni tribal allies. They form the core of the commercial oligarchy, which provides important financial support and advice for the regime’s industrial and commercial projects. They also function as bankers and money-changers. This group consists of two components. The more numerous and influential are the Huwala, or ‘Persian Arabs’, who are descendants of merchants who lived on both sides of the Gulf and are Sunni (following the Shafiite school of law). Their commercial and political ties with the Al Khalifa rulers, the British colonial administration, and Western companies enabled some Huwala families to establish prosperous multinational trading businesses. Most famous among these is the Kanoo Group, now one of the largest family-owned businesses in the Gulf. Members of Huwala families, such as the Shirawis and the Fakhroos, are found in the top echelons of the central bureaucracy and in ministerial posts.

The second component of the commercial oligarchy consists of the Najdi families, such as the Al Gosaibi and the Al Zayani. These families settled in Bahrain around the same time as the Al Khalifa, but, unlike the ruling family, they are considered non-tribal and urban. They largely follow the Hanbali school of Islamic law. This doctrinal affiliation has led to serious conflicts between certain Najdi families and the Al Khalifa. Many Najdi inhabitants of Bahrain retain some loyalty to Saudi Arabia; some have dual passports. This historical friction notwithstanding, they are generally viewed as allies of the Al Khalifa. Like the Huwala, Najdis have created flourishing international businesses based on kinship ties throughout the Gulf region. They are active in the local banking sector and hold senior government positions. Unlike the Huwala, however, the Najdis are also found in substantial numbers in the country’s security and police forces. As a rule, Huwala and Najdi families belong to the upper or middle classes, while their most prominent members are the only remaining indigenous rivals to the political and commercial power of the leading Al Khalifa sheikhs.

Shiites

The majority of Bahrain’s population is Shiite. Sectarian affiliation is a sensitive topic: the last census in which religious affiliation was recorded took place in 1941. In that year Shiites formed a bare majority (51.5 per cent) of Bahrain’s inhabitants. As per the estimates of 2023, they still constitute the majority of the national population, despite the government’s practice of naturalizing many Sunni (but not Shiite) Arabs.

Bahrain’s Shiites can be divided into several subgroups. Virtually all Bahraini Shiites belong to the main Twelver branch of Shiite Islam (the predominant branch of Shiism in the Gulf), although pockets of Bahrain’s original Ismaili Shiites have survived. The Twelver Shiites can, in turn, be divided into two subgroups, Usuli and Akhbari. Adherents to the Usuli school of Shiite Islamic jurisprudence, who, besides relying on the Koran and Hadith, turn for guidance to one of the grand ayatollahs (their Marja al-taqlid, or source of emulation) are most numerous. Far fewer belong to the Akhbari school, which relies solely on the Koran, Hadith, and consensus and rejects the Usuli reliance on a Marja.

Most of the Shiites of Bahrain and many Shiites in the coastal region between Kuwait and the UAE are Baharna, that is, Arab Shiites descended from the original inhabitants of Bahrain. Sunnis thus prefer to use the term Bahraini when speaking of the inhabitants of Bahrain, although historically the term Baharna might refer to all inhabitants of the region of Bahrain.

Historically, most Baharna were farmers, but some lived in the towns and cities and became affluent through trade, investment, or clerical occupations.

Today, Baharna form the core of the urban lower-middle class. They have their own historical quarters in the towns and cities but some live in mixed districts, side by side with Sunnis from the same socio-economic classes. The two groups share a certain national, and sometimes class, consciousness and have often presented a unified front against immigrants. At times, notably in the 1950s and 1960s, they have worked together, despite their sectarian differences, to protest their shared economic circumstances. Inter-sectarian marriages are, however, still uncommon.

The third group of Shiites comprises traders from al-Ahsa or al-Hasa, in present-day Saudi Arabia. The Hasawis speak their own variant of the Baharna Arabic dialect.

A final group consists of the Persian shopkeepers and small traders who migrated to Bahrain but have maintained their Persian roots and language (although most are bilingual). This sets them apart from the Huwala, who also have roots in Persia but are Sunni Arabs. The Bahraini Persians are often viewed by Sunnis as a fifth column, presumably receptive to political overtures and intrigues from Tehran. They are the country’s most segregated national community, concentrated in Manama’s al-Hurra and al-Ajam districts (Ajam means Persian or non-Arab).

Discrimination

When Bahrain’s new emir ascended the throne in 1999 he launched an ambitious program of political reform. There was some expectation among the Baharna that discrimination against their community would lessen, but these hopes were soon dashed. In the following years, members of Bahrain’s social underclass frequently turned to the streets to protest social inequality, sectarian discrimination, and police repression. Sometimes the protests turned violent: in December 1997 one protester died, presumably from tear-gas inhalation. In April 2008, a policeman was killed in Karzakan. Widespread unrest emerged in 2011. It flared up again at the end of 2014, after the opposition Al-Wefaq Shiite Society announced the arrest of its leader, Ali Salman, on charges of “inciting the regime and calling for its overthrow by force.” And it was renewed in mid-2019 after the execution of two Shiite activists on terrorism charges.

Regime critics contend that discrimination in Bahrain has become more institutionalised. Bahraini Shiites invariably have to wait much longer for government-subsidised housing than do their Sunni co-nationals. Top-level posts in government and the managerial ranks of the civil service are reserved almost exclusively for Sunni nationals. The national defence, police, and security forces are all dominated by the Sunni minority. While the government is believed to regularly naturalise Sunni foreigners from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Iraq, in order to strengthen the ranks of these security institutions, Shiite applications for security jobs are often rejected. In the private sector, Shiites tend to occupy the lower-paid, unskilled jobs. They form the overwhelming majority of the student population of universities but a minority of the faculty departments.

Jews and Africans

There has been a small Jewish community in Bahrain since at least the time of Muhammad, and the early 20th century saw an influx of Iraqi Jews. Many Jews resided in the country only in summer, during the pearl-fishing season. Many migrated to Israel after its creation in 1948, and others followed, after the June War of 1967. Bahrain is the only country of the Persian Gulf States to have a synagogue. The Jewish community currently numbers a few dozen people.

Many Bahrainis are descendants of slaves from Africa, who typically arrived from Oman’s territory in Zanzibar. Former slaves and their descendants adopted the tribal names of their owners, and they occupy a lower socio-economic position. Bahraini (and khaliji) music and dance has been shaped by traditions brought by slaves from Africa.

Foreigners and Non-Nationals

The British colonial authorities were the first to make an official distinction between Bahraini nationals and ‘foreigners’. Any ‘foreigner’ resident in Bahrain was required to register at the British Agency in Manama and was thereby subject to British jurisdiction. Bahrainis saw this British ‘protection policy’ as a way of favouring foreign, especially Indian, traders over local ones. This led to resentment against the Bania community (Indian traders, called Banyan in Bahrain), which persists today.

Bahrain’s first nationality law was promulgated in 1937. Under it, all residents in Bahrain who had not registered at the British Agency were considered ‘nationals’. Only a very few resident ‘Indians’ were naturalised.

Before the oil boom of the 1970s, the plurality of foreigners living in Bahrain (about 30 per cent) came from Oman. Second came Indians and Pakistanis (about 25 per cent), followed by Iranians (14 per cent) and British (8 per cent). Since the mid-1970s the number of non-nationals has risen considerably. According to the official censuses, they constituted 17.5 per cent of the population in 1971, 32 per cent in 1981, 37.6 per cent in 2001, 53 per cent in 2010, and 53.9% in 2023. The composition of the foreign population has also changed. Almost all Omani workers left Bahrain when Oman’s own oil industry was being developed in the 1970s. This exodus has been more than balanced by large numbers of migrants from the Asian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka) and, since the 1980s, East Asian countries, such as Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. In the 2020 census, 82.51 per cent of Bahrain’s foreign residents were listed as Asians. The second largest group comprised ‘other Arabs’. Less than 2 per cent came from other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Hierarchy and Discrimination

A strict hierarchy exists in Bahrain’s foreign population. GCC Arabs and Westerners with good connections (wasta) are at the top. These include businessmen and executive officers or senior consultants of big companies. Then come the non-wasta managers, consultants, technicians, and small businessmen, regardless of nationality. They live in the suburbs of Manama and intermingle in the Western-style sport- or nightclubs and luxury-hotel bars, which all serve alcohol.

In the middle position are Asians working in clerical and service jobs. Among these, (non-GCC) Arabs are generally treated better than South and East Asians. Further down the hierarchy are the unskilled or semi-skilled workers from Asia, living in cramped housing and facing serious discrimination. In certain respects, they are less well off than the Eastern European and Asian sex workers at Manama’s hotel bars, at least as to their material well-being. The much-deplored position of Asian housemaids in the Gulf varies greatly with the humanitarian standards of their personal employers. At the very bottom of Bahraini society are the Bangladeshis who offer unskilled incidental labour on the streets.

Foreign workers and housemaids face serious discrimination and even regular abuse. Bahraini law allows citizenship to Arab foreigners who have resided in the country for fifteen years and non-Arabs who have lived in Bahrain for twenty-five years, but many non-Arab expatriates’ applications for citizenship have been rejected.

Shiite Arab migrants complain of similar discrimination. Without citizenship, they are prohibited from bringing over their wife or other family members. Marriage to Bahraini nationals is extremely rare and does not automatically confer citizenship. Children of Bahraini mothers and foreign fathers remain foreigners. Moreover, when migrants turn 60 their residency permits are no longer renewed. The result is forced repatriation, no matter how long one has worked in Bahrain.

It is rare for foreigners to obtain a Bahraini passport, even when born and working in Bahrain. Excepted are Sunnis serving in the police and military, many of whom have been granted citizenship in recent years. Bahraini law does not provide for the granting of asylum or refugee status to persons meeting the criteria of the 1951 UN Convention and its 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees.

The Bahraini government has, in practice, cooperated with the UNHCR and other humanitarian organisations in assisting asylum seekers and has protected them against deportation.

Relations Between Groups

The social structure of Bahrain is one of the most intricate in the Arab world. The conventional framing of social conflict as a Sunni-Shiite issue, while containing an element of truth, is too simplistic. Conflict, even along sectarian lines, has historically been primarily about economic and political rights, which the government grants more generously to Sunnis than to Shiites. Sectarian differences have been exploited and accentuated by the ruling Sunni aristocracy for political means, but social, commercial, and political coalitions in Bahrain have almost never been formed along purely sectarian lines. Moreover, both the Sunni and Shiite communities are divided among many nationalities, subsects, social classes, and cultural, linguistic, and ethnic subgroups.

The social-pyramid model is a better way to describe the social structure of Bahrain than framing it simply as a Sunni-Shiite (or Arab-foreign, traditional-modern, or tribal-urban) conflict. By identifying the positions of the main groups of Bahraini society in the various hierarchical levels of this pyramid, the specific dynamics and structure of Bahraini society can be more easily understood. Positions within the Bahraini social hierarchy are, however, never static. They have changed throughout history, and social mobility – upward or downward – has been possible for individuals or entire clans. But social mobility has never been unlimited: one’s origins strongly determine how high one can rise – or how far one can fall – in Bahraini society.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Population’ and ‘Bahrain’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: