Coming of Islam and Qarmati Rule

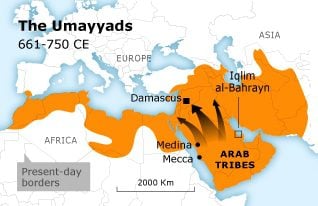

Little is known of the early Islamic history of Bahrain. The Arab dynasty of the Umayyads in Damascus (661-750 AD) probably exerted only indirect control over what was then called Iqlim al-Bahrayn (Province of the Two Seas). This Umayyad governorate, which gave the present state of Bahrain its name, covered the entire southern Gulf littoral, including its islands, from southern Iraq to the Strait of Hormuz. The area prospered particularly under the early Abbasids, the Muslim Arab dynasty that succeeded the Umayyads in 750 and transferred the empire’s capital to purpose-built Baghdad, in central Iraq. Because of the more eastward orientation of the partly Persianized Abbasids, the ancient trade routes from Iraq to the Indian subcontinent regained their importance. The inhabitants of the Bahrain archipelago, then known as al-Awal, could not help but profit from this commercial revival.

Qarmati rule

Trade in the Gulf was disrupted again after social unrest broke out on a large scale in southern Iraq, in the second half of the 9th century. Black slaves on the Iraqi plantations rose in violent revolts. Indigenous opposition groups expressed their defiance of the Sunni orthodox rulers in Baghdad through the language of heretical religious groups, among whom were the Carmathians (Qarmatis or Qaramita), an Ismaili Shiite offshoot whose adherents claimed to follow the teachings of the semi-legendary Hamdan Qarmat of Iraq. In the 890s Abu Said al-Jannabi, the mahdi of the Qarmati community of al-Awal established an independent state that comprised al-Awal and parts of the eastern Arabian mainland.

Qarmati rule was characterized by a general absence of taxes and a generous welfare system. The Qarmati state could therefore be viewed as a forerunner to the ‘welfare states’ in the Gulf that have developed during the present oil era: its social dependence on a servile underclass, mostly of black African slaves, parallels contemporary dependence on foreign labour. The Carmathians even enslaved fellow Muslims who rejected the Qarmati creed. In the 10th century, they ravaged eastern Arabia and attacked Mecca, removing the Kaaba’s holy Black Stone and enslaving many of its inhabitants. The Carmathian state finally succumbed in 1077, under the raids of Sunni Bedouin tribes loyal to the Turkish Seljuks of Anatolia, although some regional tribes continued to cling to the Carmathian doctrines until at least the 15th century.

Twelver Shiites and Jabrids

During the later Middle Ages, many Bahraini traded their radical Ismaili confession for the more quietist Twelver branch of Shiite Islam, an orientation that was less likely to provoke the orthodox Sunni powers of the time. During the 13th century, Bahrain Island became an intellectual center for Twelver theology, although the majority of the island’s inhabitants were probably still Ismaili. On the outskirts of modern Manama, one can still visit the tomb and mosque of Maitham bin Ali al-Bahrani, a famous Twelver cleric who lived and taught in Bahrain until his death in 1280 AD.

The region remained politically unstable after the fall of the Carmathians. Local power reverted to the Banu Jarwan when the Jarwanid dynasty conquered present-day Bahrain, Qatif, and al-Ahsa in 1305-1306 AD. The Ismaili Jarwanid rulers appointed Twelver imams to pivotal administrative and legal positions. Apart from their ‘official’ incomes, these clerics acquired substantial wealth and social power through the extensive date plantations they controlled and from their financing of the pearl trade. The Banu Jarwan/Jarwanids were defeated in 1330 AD by the troops of Qutb al-Din Tahamtam of the Kingdom of Hormuz and were forced to accept their Sunni kings as overlords, but the Twelver clerics retained their positions, and Bahrain continued to be an important intellectual center for Twelver Shiism.

Jabrids

Around 1460 the Banu Jarwan/Jarwanids were overrun by the Sunni Bedouin Jabrid dynasty, from Najd, in the central Arabian Peninsula. The new Jabrid rulers frequently refused to pay tribute to the kings of Hormuz, resulting in clashes with this regional power. The Jabrids also appointed Sunni Maliki judges in their territories and forced leading Twelver clerics to convert to Sunnism. In the end, however, the Jabrids failed to eradicate Shiism from Bahrain.

During their seventy-year rule most common people – peasants, pearl divers, and weavers – held on to their faith under persecution. Likewise, some Twelver clerics with independent sources of income continued to study and teach Twelver Shiite theology.

Portuguese and Safavids

The Kingdom of Hormuz and its dependencies had thrived on the spice trade from Asia to the late medieval Christian states of Mediterranean Europe, but the resurgent European polities of the early Renaissance would no longer be content to have luxury goods delivered to their doorsteps by Italian, Arab, and Jewish intermediaries.

Starting with the Portuguese seafarer Vasco da Gama in 1498, European explorers, traders, and soldiers (often working together) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in search of adventure and profit. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to build a network of trading posts and military strongholds in southern Asia and the Far East. From their base in Goa, they soon turned their attention to the Gulf. In 1515 they took Hormuz and in 1521 Bahrain, which they partly fortified but ruled only indirectly, through Hormuzi governors.

Portuguese rule

Under Portuguese-Hormuzi rule the people of al-Awal/Bahrain – from about this time the whole of the archipelago would be named ‘Bahrayn’, while ‘al-Awal’ became the designation for its main island – suffered economically. The Portuguese demanded high tribute and tariffs and attempted, with little success, to divert the spice trade away from the Gulf to their own sea route around Africa. They also took over Bahrain’s lucrative pearl trade with India by using their own vessels and merchants, thereby circumventing local traders. In 1602, however, the Portuguese were ousted from Bahrain by the Twelver Shiite Safavids of Persia. Under a Safavid governor, Twelver Shiite religious institutions were resurrected. The Safavids even persecuted Sunnis in their territories. Consequently, a substantial number of local Sunnis left the island or converted – or, in some cases, reverted – to Shiism.

The Safavids ruled until 1717 when they were chased from the islands by invading Omanis. Thus began a period of political turmoil, intrigue, invasions, and destruction. The German explorer Carsten Niebuhr, who visited Bahrain in 1763, when it was temporarily back in Persian hands, recorded in his journals that only 60 of the original 360 towns and villages of the islands were still inhabited. Out of the political violence and confusion of the 18th century emerged two unevenly matched powers: the Al-Khalifa and the British. Together they would shape most of the modern history of Bahrain.