Introduction

In the summer of 2006, shortly after Google Earth became publicly accessible, the Ministry of Information blocked the site, but, until then, the people of Bahrain could, for the first time – with just a few mouse-clicks – see the sharp contrast between the vast green palace grounds and coastal areas accessible only to members of the ruling family and the densely populated, dusty, predominantly Shiite villages. The inequality that they knew existed was now visible.

The censorship only generated more interest, and screenshots of the banned pictures circulated widely. Private landholding in Bahrain has long been a sensitive issue. Well into the 20th century the Baharna, the indigenous Shiite landowners, suffered the arbitrary confiscation of their properties by the ruling family and its allies. According to opposition sources, 95 percent of the nation’s land area is now privately owned, 80 percent by the royal family itself. Since the emergence of the oil economy in the 1950s, when industrial and real-estate development became far more profitable than agriculture – especially date farming – former agricultural land has been rapidly cleared for the construction of luxurious residential areas, office blocks, and golf courses. The former agricultural labourers and pearl fishers have flocked to the cities, where most live in the poor, crowded, working-class neighbourhoods of Manama and Muharraq.

Family

Bahraini society remains deeply patriarchal. The husband and father heads the nuclear family and watches over the morality of his wife and children and unmarried females in the extended family. In a divorce, the nation’s religious courts generally grant mothers custody of their daughters under age nine and their sons under age seven, at which point custody generally reverts to the father. The father retains guardianship until his children reach the age of twenty-one. Even a non-custodial father retains the right to make all legal decisions regarding his children. Women have the right to request divorce in the religious courts, but the courts can deny the request.

Women

Shiite women may (under Shiite law) inherit property, but Sunni women, governed, in personal status matters, by Sunni Maliki law, do not. But values do change. Rapid urbanization, public education, and exposure to more liberal attitudes through modern media and travel have led Bahraini women to spend more and more time outside the house. Until recently, the country had even been a pacesetter among the Arab Gulf states in women’s education and employment. While the other Gulf Cooperation Council countries and emirates are catching up with Bahrain or – as in the case of Dubai – have apparently surpassed it in educational and vocational possibilities for women, the country still has a relatively high ratio of women in the workforce. They make up 54 percent of the public sector workforce and hold 45 percent of leadership positions in official state agencies. In the private sector, women comprise 35 percent of the workforce, hold 17 percent of board seats, and occupy 35 percent of managerial roles. These figure are even more impressive, given that many Bahraini women stop working when they marry, leaving only a few years between graduation and marriage to be active in the job market. But even this pattern is changing: Bahraini women increasingly re-enter the workforce after having given birth.

Education

Bahrain’s formal school system dates back to 1932 and is the oldest in the Gulf Cooperation Council states. Since the promulgation of the 2005 Education Act, education is compulsory and free for all children, citizen and non-citizen alike, from ages 6 to 15 (corresponding with the primary and intermediate levels). Although the new law imposes fines on parents whose children fail to attend school, the authorities are not known to enforce this rule strictly. The enrolment of girls at the non-compulsory secondary level is almost 100 percent and for boys about 90 percent. According to Nawal Ibrahim Al-Khater, Bahrain’s Undersecretary at the Ministry of Education, during the 2023-2024 academic year, approximately 155,000 students were enrolled in the kingdom’s 209 government schools, while over 90,000 students attended the 80 private schools.

The most important institutions of higher education are Bahrain University and Arabian Gulf University. There are twelve private universities and several specialized institutes.

Skills Shortage

Two thirds of the jobs created in Bahrain’s private sector go to foreigners. Private employers prefer foreign workers over indigenous, partly because the latter often lack the necessary skills. The country suffers, in particular, from a lack of vocational training. To remedy this and as part of a broader drive to reform the Bahraini education system, the Bahrain Polytechnic was opened in 2008. It offers two-year and four-year courses in areas such as marketing, advertising, and engineering.

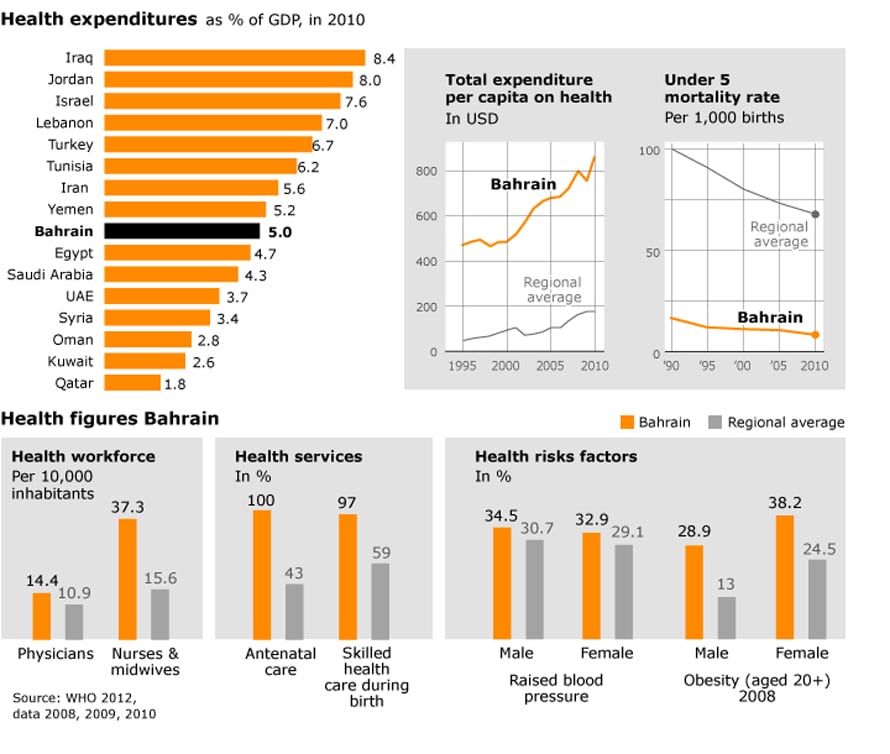

Health System

Bahrain was the first Gulf State to offer its citizens free health care. Today, according to the UN Data (2023 figures), Bahrain has a life expectancy of 80.67 years for males and 81.99 for females and spends 4.5 percent of its GDP on health care. Ministry of Health facilities provide health care free to Bahrainis and subsidized health care to non-Bahrainis. Bahrain scores well on the major health indicators: its immunization rates are high and its maternal mortality rates low.

WHO recently warned that modern diseases – e.g., cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer – and injuries ‘are rising dramatically in Bahrain, and represent the leading causes of death in the country’. It states that tobacco smoking among both men and women is ‘a concern’ and obesity is ‘an emerging major problem’. Infectious diseases are largely under control in Bahrain, ‘due to a very efficient immunization programme’.

Infectious diseases of childhood have been almost eradicated, but viral infections, such as gonorrhoea, syphilis, and hepatitis, are on the rise. The threat of heat stroke is most serious among foreign construction workers: there is an official ban on outdoor work between noon and 4:00 PM during July and August, but employers frequently ignore this.

Crimes

Bahrain has a low crime rate. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Bahrain had a reported homicide rate of 0.2 deaths per 100,000 in 2022.

According to Amnesty International, Bahrain imposes the death penalty, but only on non-nationals. Amnesty’s 2023 report reveals, that by the end of 2023, over 40 people were under sentence of death . Violent street crime is rare but on the rise. The most common petty crime is the snatching of wallets and mobile phones from people’s cars or pockets. Some sources lay the blame on South Asian migrants, while others assert that South Asians are the most common victims, claiming that groups of local youths attack and rob South Asians on the streets. International criminal organizations traffic in narcotics for the small but growing local drugs market (although not on the level of Dubai, a major transhipment port). While the penalties for drugs use are severe, the law does not specifically prohibit human trafficking.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Bahrain’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: