Introduction

The national culture richness in Bahrain is a natural reflection of the richness of its civilization, which extends deep into history for more than five thousand years. The small Gulf kingdom always had a distinguished presence among the successive human civilizations, to become one of the centers of intellectual and cultural influence, and a forum for cultures and religions, due to its geographical location, as global trade convoys passed through it on their way to and from the countries of the Gulf, the Mediterranean, the Indian subcontinent and the Far East.

Although the Kingdom includes many different sects and religions, Islam remains the predominant religion for the majority of the population, as it is possible to notice the influences of the Islamic and Arab culture, with its rich heritage, traditions, and arts, on the various forms of life in the country.

These influences can be noticed in the way locals dress, as people tend to wear modest clothes. The traditional clothing worn by the locals is a “thobe” for men and an “abaya” for women. Although the traditional dress code is not mandatory, residents often tend to dress modestly.

On the other hand, traces of Islamic architecture can be seen through many installations in the Kingdom. Islamic architecture is apparent especially in religious buildings such as mosques, places of worship, and libraries as well as neighborhoods and sustainable homes.

African culture was one of the most influential cultures on Bahraini culture because most of the pearl divers in the Gulf were slaves from East Africa or the offspring of former slaves, which can be seen in arts such as music and singing, and most of the musicians in Bahrain were and still are of African origin. This influence extended to some widely popular types of dance, not only in Bahrain but in the Gulf countries in general.

The Kingdom has been keen to provide the legislative and institutional framework by establishing the “Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities” according to Decree No. (10) of 2015 as a body subordinate to the cabinet, concerned with all the functions that were carried out by the Ministry of Culture and other official agencies concerning the protection and development of the culture, national heritage, antiquities and museums sector, and the encouragement of artistic and theatrical movement.

Bahraini literature has a distinct tradition, as most literary works were produced in the classical Arabic style. Among the well-known contemporary poets Qasim Haddad, Ebrahim Al-Arrayedh, and Ahmed Muhammad al-Khalifa. But many of the younger poets were more influenced by Western literature.

For more about Bahrain’s culture, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Creating a National Culture

When the Lebanese writer Ameen Rihani visited Bahrain in the late 1920s he was struck by the sight of partially naked Bahrainis wading through the coastal mud at low tide, in order to reach the small boats that shuttled passengers between Manama and Muharraq. ‘No bathing scene along the Jersey coast can surpass in its nudity and merriment this of Bahrain’, Rihani commented in his travel account Around the Coasts of Arabia. In fact, the scene would have caused a scandal in Britain at the time, but in Bahrain it was apparently not considered immoral – at least among the poorer parts of the population – for a woman to publicly roll her dress up high above her breasts, while keeping the obligatory veil in place. When Rihani hesitated to photograph a particularly ‘generous’ lady, his local companion put him at ease with the reassuring words, ‘It is something familiar; there is no harm in taking the picture’.

References to ‘traditional’ Bahraini culture today often present a heavily sanitized – even invented – representation of the nation’s actual cultural traditions. ‘Traditional’ public nudity in Bahrain was effectively banished by the British colonial authorities. Although Bahraini culture is liberal by Gulf standards, foreigners follow somewhat more modest practices, at least in public places.

Official presentations of Bahraini culture in the nation’s museums, ‘traditional-art’ centres, history books, and ‘heritage’ publications, are generally shaped by the norms, tastes, and socio-political considerations of Bahrain’s dominant socio-political groups. Behind this more or less conscious construction of an official ‘national Bahraini heritage’ are two main driving forces. The older of the two arises from the continuing lure of the traditional Arab cultural powerhouses of Cairo, Beirut, and, more recently, London. Urban Arab cultural influences from these cities really began to affect Gulf cultures at the beginning of the oil era. These influences have been overwhelming because of the massive influx of Egyptian teachers since the 1950s, the local tradition of sending young members of the elite to prestigious schools and universities in Cairo, Beirut, and London, and, above all, the local domination – until recently – of Egyptian, Lebanese, and London-based Arab mass media.

The second main force influencing the presentation of Bahrain’s traditional culture flows from the process of creation and development of the Bahraini nation-state, which has been based on the assumption that the monopoly of power will remain in the hands of a small elite, consisting of prominent members of the Al Khalifa and the leading Sunni merchant families. In order to maintain this status quo – which can be seriously harmed when frustration among parts of the population is translated into demands for political emancipation – the construction of a civic myth is being strongly encouraged by the authorities. Civic myths have recently been defined by the American Brooke Thomas as ‘compelling stories about national origin, membership and (shared) values that are generated by conflicts within the concept of citizenship itself’. In Bahrain, this ‘compelling story’ about the nation’s history, citizens, and values is designed not only to strengthen national cohesion but also to legitimize the status quo, especially the dominant position of Sunni citizens and the ruling family.

Khaliji Music

In recent decades the culture of the Gulf has also started to influence the wider Arab world, reversing the traditional direction of cultural influence. Khaliji (Gulf) music, in particular, has acquired audiences far beyond the Gulf. Egyptian and Lebanese popstars often include khaliji songs on their albums. The Saudi Mohammed Abdu (or Abdo) or the Kuwaiti Nabeel Shuail are well known by lovers of Gulf music.

Khaliji is a typical marketing term, comparable to catch-all musical labels such as ‘Latin’. It therefore covers a range of musical genres that were known only by individual local names a generation or two ago. Among the most prominent in Bahrain has been the genre called fijiri (to dig up, possibly referring to the pearl divers), a range of different types of song traditionally performed by pearl divers. Because most pearl divers in the Gulf were East African slaves or former slaves and their descendants, most musicians in Bahrain have been and still are of African origin, including the three mentioned above. The African influence on ‘Bahraini’ or khaliji music can be heard clearly in its typical use of a pentatonic scale and 6/8 and 12/8 beats. This maritime musical tradition differs from that of the city or the desert in its use of instruments that travel well aboard ship, such as drums and clay pots.

While popular Arab music from the Mediterranean Arab world has been strongly influenced by Western music, the popular music of the Gulf has generally retained more traditional local elements. This is apparent not only in Bedouin, African, and Indian influences on its styles but also in the lyrics. While Egyptian pop stars often seem to copy their lyrics from the likes of Michael Jackson and Shakira, the lyrics of popular Gulf singers tend to draw on age-old classical Arab tradition.

Khaliji Dance

The best known folkloric dance in the Gulf is the arda, the traditional Bedouin war dance. It is performed by singing men who brandish their rifles or swords in a valiant manner, while they dance in a circle to a 6-beat rhythm that is unmistakably African. Nowadays, Bahraini arda performances have strong nationalistic overtones. The liwa is not a dance in itself but rather a style of music (for men only) meant to dance to. It is often performed on festive occasions and is closely related to the originally African zar ritual for spiritual healing. In Bahrain, liwa is reckoned among the funun al-wafida (the arts of the newcomers, i.e., East Africans). An ‘African’ dance (for females only), which is very popular in the Gulf today – although performed exclusively in private – is called malaya. This is a wild, sensual dance form, probably related to soukous from central Africa. It is officially frowned upon because of its explicit sexual movements, but Rihani would love to have watched the scantily clad and often veiled Gulf women (or, more often, Russian or Eastern European women) performing malaya in the growing number of clips dedicated to the genre on YouTube.

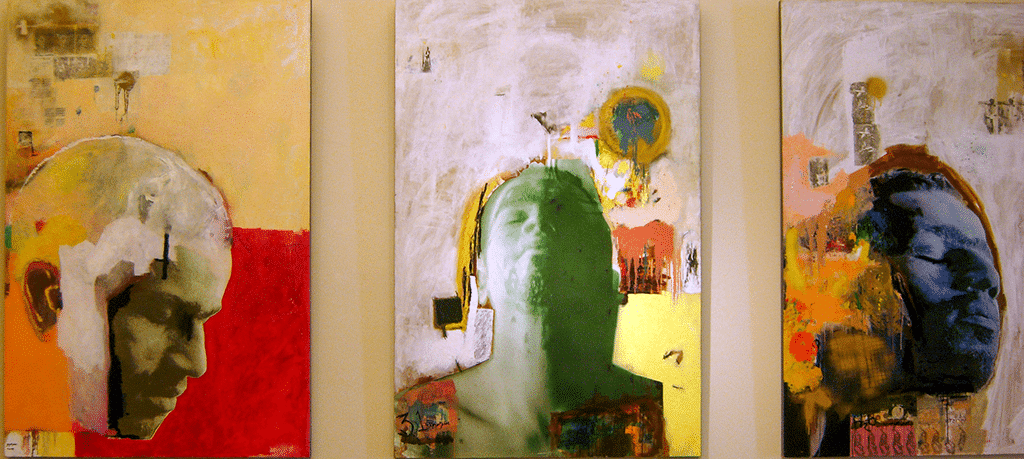

Visual Arts

In Bahrain’s visual arts, such as painting and drawing, Western cultural influences are easily discernible. Local artists tend to add local colour or ‘Islamic’ motifs to their work, but the result often comes across as bland and uninspired, probably due to social or artistic conservatism and/or commercial considerations. Even more surprisingly, many local artworks employ old-fashioned Western orientalist stereotypes, such as colourful souks and veiled women bearing water jars. This is a reflection of the present craving for classical orientalist art in the Arab world.

Bahrain’s film industry is small. It most prominent director is Bassam al-Thawadi (al-Hajiz, The Barrier, 1990; Zair, Visitor, 2000; A Bahraini Tale, 2006.

National 'Dress'

What is described as ‘national dress’ in virtually all Gulf handbooks, is, in fact, a local variation on the traditional dress of the tribal Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula. In Bahrain, the thawb or thobe, a long white cotton gown, is still worn by many male citizens. In winter, the thobe is usually of a darker colour, blue or grey, and of heavier material. The headscarf (ghutra) is generally white in Bahrain. On formal occasions and in winter a gold-embroidered gown, made of silk or wool and usually brown or black, might be worn over the thobe. Bahraini women often wear an abaya, a loose black coat, over their Western-styled clothes. The hijab (head-scarf) has recently become very popular.

Soap Operas

Television soap operas are very popular in Bahrain. Bahrainis first encountered these musalsalat in Egyptian productions that took the Arab world by storm in the early decades of Arab television entertainment. In the 1980s, Gulf countries, beginning with Kuwait, began to produce their own TV dramas, and local Bahraini productions began to appear in the 1990s. The influence of the old soap operas from Cairo is still obvious. The British linguist Clive Holes has examined several boxed sets of Bahraini home-grown series from the 1990s and concluded that ‘This type of musalsal has been cloned directly from a thousand others made in Egypt in the last 30 years and transposed into a Gulf setting, complete with the Louis de Lebanon furniture in the living room and the obligatory Mercedes in the drive’. Like the classical Egyptian musalsalat, their Bahraini rip-offs make no mention of social problems such as unemployment or discrimination.

But the Bahraini soap-opera actors do not speak in the Cairene dialect or in Modern Standard Arabic, the literary lingua franca of the Arab world. Instead, they speak exclusively in the unmistakable dialect of Bahrain’s Sunni tribal Arabs. Even in the nostalgic, quasi-historical series, professedly meant to ‘link subsequent generations to their popular culture, its history, and its customs’, ‘typical’ Bahraini characters who must certainly be Shiite – such as the agriculturalist, an exclusively Shiite occupation – speak a Sunni dialect and wear traditional Sunni dress. Casual observers will probably conclude that Bahrain never was an country divided along ethnic and sectarian lines, where Sunni Arabs and Shiite Baharna lived apart, worked apart, and fostered their own separate identities. In Bahrain’s musalsalat, every ‘real’ Bahraini speaks and dresses like a Sunni Arab, even while performing typically Shiite activities. This way Bahraini television producers – almost exclusively Sunni – help mould the nation’s civic myth.

Sports

Bahrainis, like most Gulf Arabs, enjoy watching sports. Camel racing and, especially, horse racing are very popular. Every Friday in the colder months horse races are held at the ten-thousand-seat Sakhir Racecourse near Awali, although the traditional bookmaker has, as everywhere in the Gulf, been banished, in accordance with Islamic law.

Bahrain was the first Arab country to open a Formula 1 racetrack. The Bahrain International Circuit can accommodate seventy thousand spectators and business VIPs. Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher, as the winner of the first Bahrain Grand Prix (2004), was sprinkled with pomegranate juice and rosewater instead of being drenched in champagne.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Bahrain’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: