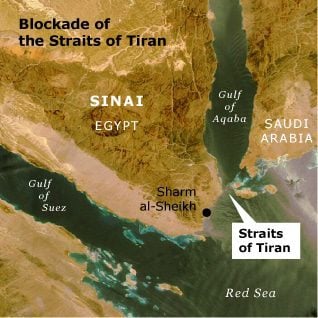

The blockade in the Straits of Tiran led to nothing, apart from some ineffectual attempts by the Israeli government to draw the United States and the Sixth Fleet into its camp. When this effort did not succeed, Jerusalem considered sending an Israeli ship to lift the blockade and provide a reason to start a war.

President Johnson however told Prime Minister Eshkol that the United States would side squarely with Egypt if Israel provoked the Egyptians and war broke out as a consequence. As one dovish Israeli cabinet minister commented: ‘The Straits were closed until 1956. Did it threaten Israel’s security? It did not.’

Finally, the so-called redeployment of Egyptian troops, carried out in mid-May, was not drastic or dramatic at all. It was more of a routine change for optical reasons. However, on the Israeli side, this was – for whatever reason – erroneously translated into a major threat that fatally undermined the assumption that the country would only have to deal with one enemy at a time.

The most telling proof of how wrong this assumption was and how unprepared the ground forces of its three Arab neighbours, especially Egypt’s, were for an attack on Israel, has been the June War itself. At the end of the second day, on June 6, the Egyptian army in the Gaza Strip was completely overrun and disarmed, three groups of Israeli tank forces were speeding unopposed southward through Sinai, and any organized military resistance to speak of was hard to find.

The Syrian ground forces in the north were almost paralyzed from the beginning and needed days needed to recover, while the Jordanian army, the most active of the three armies and fighting fiercely around Jerusalem, soon proved to be no match for the Israeli forces.

The formal decision to start the June War was taken on the morning of Sunday, June 4 by the Israeli cabinet. The night before, Meir Amit, the head of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad, had returned from Washington, where he had met with his CIA counterparts, whom he had sounded out about what Israel could expect from the United States. His report to the Israeli political and military leaders on the evening of June 3 sealed the resolve of Eshkol to go to war and no longer postpone matters.

One of Amit’s major conclusions was that the United States would not act alone in the question of the blockade of the Straits of Tiran and was still trying to muster other nations to resolve the issue. To underline this position, President Johnson sent a message to Eshkol that same weekend that he wanted more time for this effort to succeed, a request that at that moment was no longer relevant for the Israeli government and therefore ignored.

More important was the impression Amit conveyed to the Israeli cabinet and to the generals about the informal opinion in Washington on Israel unleashing a war on its own. It seemed that the heads of the CIA and important advisors to Johnson, except Secretary of State Dean Rusk, had more or less accepted the idea that Israel was going to take on its Arab neighbours and use its overwhelming military strength to subdue them.

The main thrust of their advice was something like: ‘Do not fire the first shot’, and ‘Let Israel appear to defend itself’. American Minister of Defence Robert McNamara for one was mainly interested in the question of how long the war would take Israel. Amit’s answer was: ‘One week’.

Eshkol found himself reassured by what Amit had experienced during his short visit to the United States and felt that Washington may not have given the green light, but at least the orange sign. The cabinet meeting on the morning of Sunday June 4 was not much more than a formality. Eshkol and Dayan were given the authority to decide the precise moment the war should start, and in order at least to appear to have discussed something of substance the press was told that the cabinet had approved a cultural agreement with Belgium.

A little later that same Sunday, Eshkol, and Dayan decided to start the war the next morning. That night, in line with earlier discussions and external advice, Dayan ordered the Israeli censor to maintain a ‘fog of war’ until the evening of the next day. He told the censor: ‘For the first 24 hours we have to be the victims.’ Fully in line with this, Kol Israel Radio broadcast on June 5 at 8.10 a.m. that the Egyptians were attacking Israel, thus setting the tone for a completely misleading information campaign that has yet to be equaled.

The June War of 1967 turned out to be a stunning victory for Israel, resulting in the conquest of all the territories intended and not (directly) intended to be taken: Sinai, Gaza, East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Golan Heights. Israel occupied parts of Egypt (although Sinai came under full Egyptian authority again in April 1982, after the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty, signed in 1979), Syria (the Golan Heights were annexed by Israel in 1981), Jordan (which renounced all claims to the West Bank in July 1988) and the Palestinian territories. Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1980 and laid claims to numerous Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

This war, contrary to the myth of having been unavoidable, can be seen as an example of a pre-emptive strike. The Arab military forces, which Israel considered to be lethally hostile on 5 June 1967, did not at that moment pose the immediate deadly threat imputed to them by the Israeli political and military elite. The June War has been and still is a momentous event in the history of the relations between Israel and its Arab neighbours. And as one of the political leaders involved at the time, Menachem Begin, later admitted: it was a war of choice.