Introduction

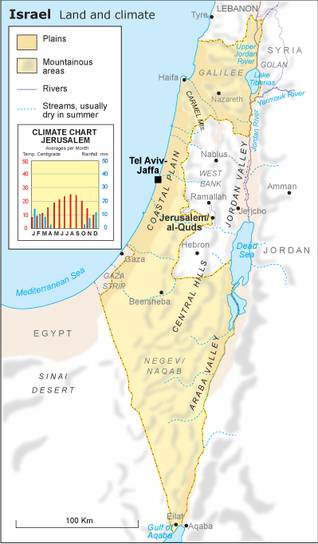

Historical Palestine has been shaped by the forces of geology and climate. The country is positioned along a fault line where tectonic forces are tearing the African crustal shell apart, producing the earth’s largest and deepest rift.

The fault line runs from southern Africa all the way up to Turkey. The same tectonic forces caused the uplifting of two parallel mountain ridges, embedding the rift.

In two places, the rift is exceptionally deep, and is filled with water from adjacent heights: Lake Tiberias in the north and the Dead Sea in the south. North of the Dead Sea the rift is known as the Jordan Valley, south of it as the Arava (Araba).

The mountain ridge functions as a barrier that catches seasonal winter precipitation from the west. It also serves as a barrier between the relatively mild Mediterranean climate and the hot and arid desert to the east.

The traditional restriction of cultivation and habitation to the mountain’s western slopes has created a narrow extended zone of life in between the desert and the sea, forming a land bridge between the continents of Africa and Eurasia.

Besides this significant difference between east and west, a distinction must be made between the country’s north, which is wetter and cooler, and the south, which is drier and hotter. Historical Palestine lies at a critical junction on these axes. Facing arid terrain east and south and the open sea to the west, it occupies a marginal position in the Levant.

Landscape

As the country’s structural spine, the mountain ridge has created three distinct parallel landscapes, all stretching from north to south. The area west of the ridge is made up of the coastal plain. It is broader in the south and gradually narrows to the north, where it also becomes more verdant. The mountain ridge itself forms a sizeable, elongated plateau that reaches heights ranging from 1,000 to 1,200 metres. The plateau is indented by numerous valleys (wadis) on both sides, which over time were carved out by seasonal rains.

The western slopes are green and fertile, the eastern slopes are generally arid and bare. The area east of the ridge forms a desert valley named after the Jordan River. It extends from north of Lake Tiberias in the north to the Dead Sea in the south, where it drops to 400 metres below sea level. The Jordan River is the only stream in the country which can be termed a river. However, both Israel and Jordan have constructed large irrigation channels away from the stream in order to tap most of its natural waters. As a result, the river has turned into a muddy, polluted trickle. From the Dead Sea the desert valley abruptly widens toward the Gaza Strip in the west, opening up to the Negev (Naqab) Desert which geographically forms part of the Sinai Peninsula. Just as the mountain ridge forms a climate barrier in the north, the greater distance from the Mediterranean Sea in the south gives free reign to the desert climate of the Negev.

The line south of Wadi Beer Sheva (Beersheba) – in between the Dead Sea and the Gaza Strip – forms the country’s most notable natural boundary. South of it there are small cultivated areas where less than 1 percent of the country’s population lives.

Historical Palestine encompassed both banks of the Jordan River, stretching eastward over a parallel mountain ridge until it reached the vast expanse of the Eastern Desert. It was only in recent times that Palestine’s eastern half was separated from its western core when Great Britain, after having conquered the country in 1917, decided to turn the eastern half into the Emirate of Transjordan, later to be renamed the Kingdom of Jordan.

The western half retained the name of Palestine until more than three quarters of its area came under control of the State of Israel in 1949. What remained was its mountainous inland core and a tiny section of the coastal plain, the first becoming known, at that time, as the (Jordan River) West Bank, annexed by Jordan, the second as the Gaza Strip, administered by Egypt. Both regions were subsequently conquered by Israel in 1967 (see the June War). Today, the two territories are increasingly known as the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).

Water

Israel’s water supply has faced many challenges since the country’s establishment in 1948. Besides the naturally arid climate, consecutive years of drought and rapid population growth, rising living standards and political tensions in the region have put great pressure on the country’s water resources.

The main freshwater resources in Israel are Lake Kinneret, the Jordan River, the Coastal Aquifer and the Mountain Aquifer. It is important to note that all of Israel’s freshwater resources are shared. The Mountain and Coastal Aquifers are shared with Palestine, the Jordan River is shared with Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria, and Lake Kinneret is shared with Syria. Almost all of these resources are overexploited and recent drops in water quality and quantity have underscored the fact that current use is unsustainable in the long term.

Israel has developed innovative solutions to address its water challenges. The most significant of these are desalination and wastewater reuse. Desalination production was estimated at 307 million cubic metres per year (MCM/yr) in 2011, enough to fulfil around 40% of Israel’s drinking water needs. This amount is set to increase significantly as water demand rises. Treated wastewater is primarily used to meet the high water demand in the agricultural sector. Production of this alternative source of water is also expected to increase as the population grows.

For more on Water in Israel, see our Israel file on Fanack Water.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Geography’ and ‘Israel’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: