When war broke out, the Israeli Armed Forces lacked heavy weapons and Israel’s Air Force had an inventory of only nine obsolete planes. This hiatus was largely filled by a deal with Czechoslovakia (with the consent of the Soviet Union) that provided for tens of thousands of light weapons and two dozens of Avia S-199 fighter aircraft – a Czech version of the wartime German Messerschmitt Me-109. (See also: Arab-Israeli Wars)

The opposing Arab and Palestinian forces consisted of loosely organized militia in Palestine itself, with an estimated strength of some ten thousand men, backed by the armies of the neighbouring states of Syria, Egypt and Jordan. These had several tens of thousands of soldiers, equipped with heavy weapons such as artillery and tanks.

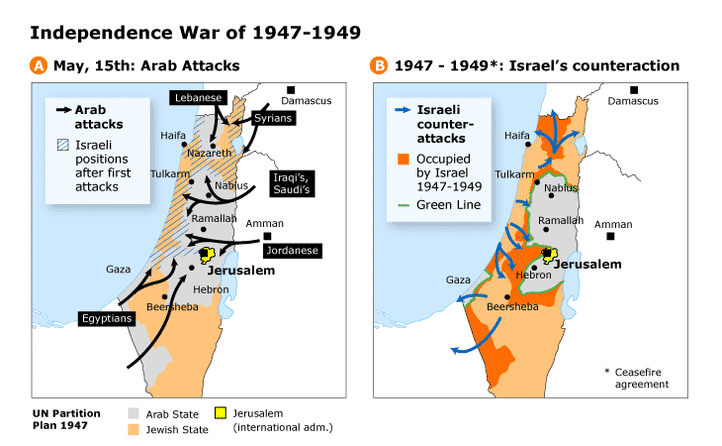

The Arab offensive was not well coordinated, mostly because the national Arab commands did not cooperate. Gradually the – at least on paper – first outnumbered Israeli forces grew in quantity and quality and gained the upper hand.

In the end, armistice agreements, concerning among other things armistice lines and exchange of prisoners of war, were concluded between Israel and Egypt (24 February 1949), Israel and Lebanon (23 March 1949), Israel and Jordan (3 April 1949), and finally between Israel and Syria (20 July 1949). (See also: Arab-Israeli Negotiations)

As a result, Israel now controlled 78 percent of the former mandated territory of Palestine (21,000 square kilometres), 22 percent more than the Partition Plan had foreseen. Of the remaining 5,200 square kilometres, Transjordan (from then on called Jordan) retained the West Bank of the Jordan River and the eastern part of Jerusalem, while Egypt took control of the small strip of land around the city of Gaza on the Mediterranean coast.