The violent birth of the State of Israel created one of the most sensitive issues in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict: the problem of the Palestinian refugees. The Palestinians’ flight started as early as November 1947, when the first skirmishes between Jewish and Palestinian militias broke out throughout the country.

The violent birth of the State of Israel created one of the most sensitive issues in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict: the problem of the Palestinian refugees. The Palestinians’ flight started as early as November 1947, when the first skirmishes between Jewish and Palestinian militias broke out throughout the country.

It reached a peak from April to July 1948 (namely from the weeks that preceded the declaration of Israel’s statehood to the time when the main Palestinian cities surrendered), when over 725,000 Palestinians went into exile or became internally displaced.

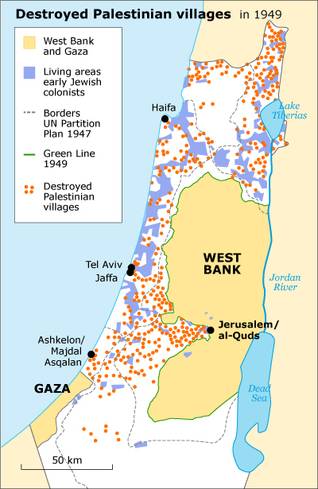

The last 1948 Palestinian exiles were the inhabitants of al-Majdal Asqalan (today’s Ashkelon), who were expelled in early 1951. In 1949, the remaining Palestinian population in Israel amounted to about 150,000, versus a Jewish population then estimated at 900,000.

Ever since 1948, the Israelis and the Palestinians have tried to impose their own narrative. Successive generations of Israeli officials have maintained that the Palestinians left their homes following orders from their own leaders, or voluntarily. On their part, the Palestinians contend that they had been expelled – or transferred – forcibly from their homes.

Tapping into a wealth of previously classified state and private papers, a number of ‘new’ Israeli historians have, since the mid-to-late 1980s, challenged the official Israeli version of a voluntary exodus. Some, including Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, have given credit to, and even reinforced, the Palestinian narrative, shedding light on the existence of a pre-conceived transfer plan.

Others have contended that forcible transfer and expulsion measures were just one of a series of factors that also included psychological warfare and fear of Jewish attacks. A proponent of this view of events of 1948-1949, is Benny Morris, another Israeli historian, who once stated that ‘the Palestinian refugee problem was born of war, not by design, Jewish or Arab’.

However, the core issue is not so much the conditions of departure, rather than Israel’s refusal to allow the refugees to return to their homes, in accordance with the provisions of relevant international law. The role of Israel in the creation of the refugee problem should indeed be considered in light of the measures its leadership adopted as early as 1948 in order to secure its Zionist project.

These have included the destruction of nearly two-thirds of over 500 abandoned Palestinian villages as well as the adoption of a set of legal regulations aimed at expropriating Palestinian landowners. Amongst these stand the Emergency Regulations on the Cultivation of Abandoned Lands (June 1948) and on the Absentees Property (December 1948) that were later embodied in the December 1950 Absent Property Law, under which the refugees’ properties were nationalized. In 1953, the Land Acquisition Law further allowed the confiscation of land for military and Jewish settlement purposes.

Estimates of the ‘1948 refugees’ vary from a low of 520,000 (initial Israeli official estimates) to a high of 850,000-900,000 (initial Palestinian sources). However, most observers today concur that the estimates of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission (ESM) are the most accurate. According to the ESM, in September 1949 the total number of refugees did not exceed 774,000, including 48,000 displaced persons in Israel proper: 17,000 Jews and 31,000 ‘Arabs from Palestine’.

The remaining 726,000 refugees settled in the West Bank or in neighbouring Arab territories: in the West Bank 280,000, in Jordan 70,000, in Syria 75,000, in Lebanon 100,000; in the Gaza Strip 190,000, in Egypt 7,000, in Iraq 4,000, in Israel 48,000 (internally displaced persons) (UN Survey Mission for the Middle East, November 1949). Out of the total of 774,000 refugees, it was estimated that 147,000 were self-supporting, resulting in some 625,000 refugees in need of relief assistance.

This became the task of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for the Near East (UNRWA), which set up 53 refugee camps on both sides of the Jordan River, in the Gaza Strip and in Lebanon and Syria. Today the UNRWA provides 4.6 million (out of an estimated total of 6.4 million) Palestinian refugees in the camps with housing, food, health care, and education.

One thing was clear: the Palestinian community in Palestine had ceased to exist as a social, economical and political entity. In the collective memory of the Palestinians the events of 1948-1949 live on as al-Nakba (the Catastrophe)