Introduction

The first newspaper to appear in the region of Transjordan, a British mandate at the time, was al-Jarida al-Rasmiya, published in 1923. A number of private weekly publications emerged throughout the decade, but the dissemination of information remained closely controlled by British rulers until the country obtained independence in 1946, and with redefined borders was renamed Jordan in 1950.

In 1953, the country’s first press law was passed, which outlawed the publication of content that was contrary to the ’principles of the kingdom’ or ’national sentiments’, while also stipulating that news regarding the royal family had to be pre-approved.

Nevertheless, a relatively open media environment prevailed until a failed coup attempt in 1957 prompted King Hussein to clamp down on outspoken media outlets and engender a more loyal, passive press.

Jordan’s first radio station was established in 1950 in the West Bank city of Ramallah, which Jordan had annexed in 1948 and controlled until 1967. This was followed by a radio station based in the capital Amman in 1959.

Jordan Radio, the state-owned corporation that would oversee the spread of the country’s radio network, was established in 1956.

Television was relatively late to arrive in Jordan compared with other countries in the region. By the time the Jordanian government established the first national channel in 1968, the country already had an estimated 10,000 TV sets receiving broadcasts from neighbouring countries.

Initially, Jordanian television was used primarily to provide information on the government’s policies and decisions.

A second channel was established in 1972, broadcasting content in English; French-language programming was added in 1978. The Jordanian Radio and Television Corporation, which brought the state radio and television apparatus under one organization, was established in 1985.

By the late 1980s, the Jordanian media environment consisted of four daily newspapers, three radio stations and two television channels, all state-owned.

In line with growing external influences caused by the region-wide spread of satellite television technology, coupled with declining natural resources and mounting internal pressure for greater freedoms, the media environment subsequently underwent a liberalization process.

The 1993 Press Law was more liberal than its predecessor, referring press misdemeanours to civil courts, for example, yet retained restrictions upon permissible content. Between 1993 and 1997, the government licensed more than 40 private or party-affiliated publications.

Yet the liberalization process was short lived and King Hussein, facing growing criticism over the Israel-Jordan peace treaty, amended the press law in 1997 to increase the necessary capital requirements for starting a newspaper, effectively putting dozens of independent publications out of business.

In 1998, a new press and publications law was passed, further increasing capital requirements. It once again stipulated that publications could not publish material contrary to ‘national responsibility’ and the nation’s values or content that ’disparages the royal family’ or leads to ‘moral corruption’.

When King Abdullah acceded to the throne in 1999, there were initial signals that the media environment would become freer. The 2003 Audio Visual Law ended the government’s monopoly on radio and television broadcasting, and in 2007, Jordan became the first Arab country to pass a freedom of information law.

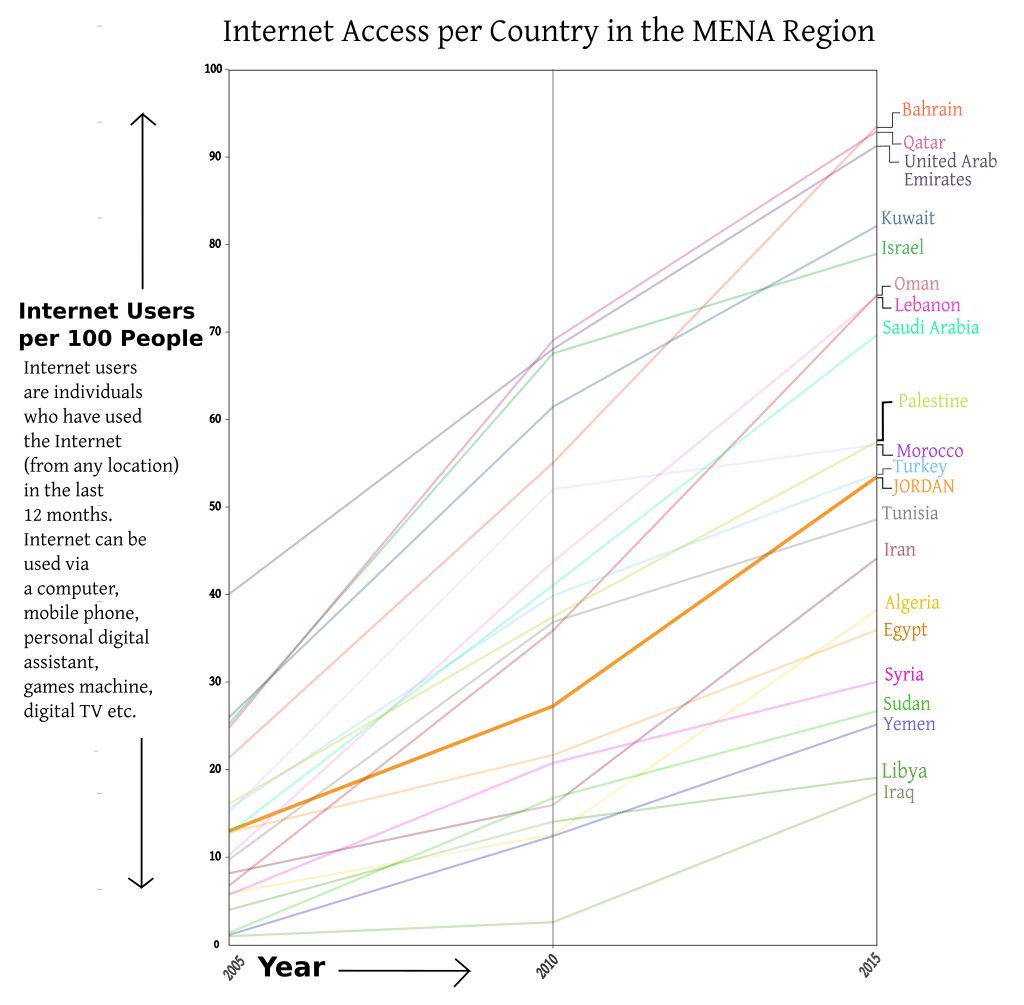

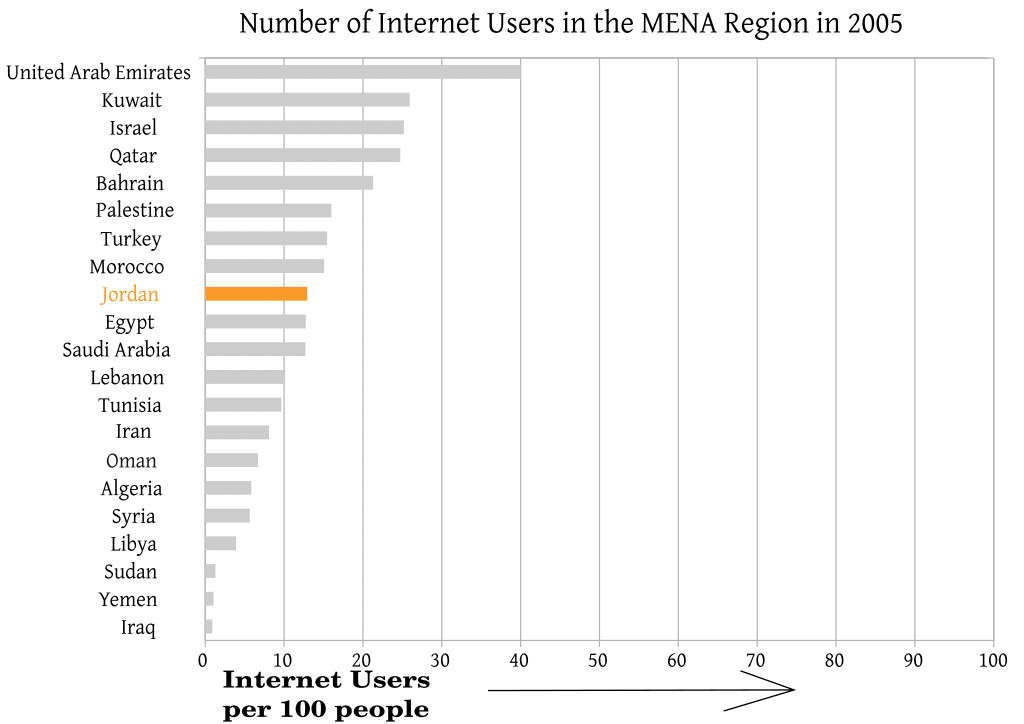

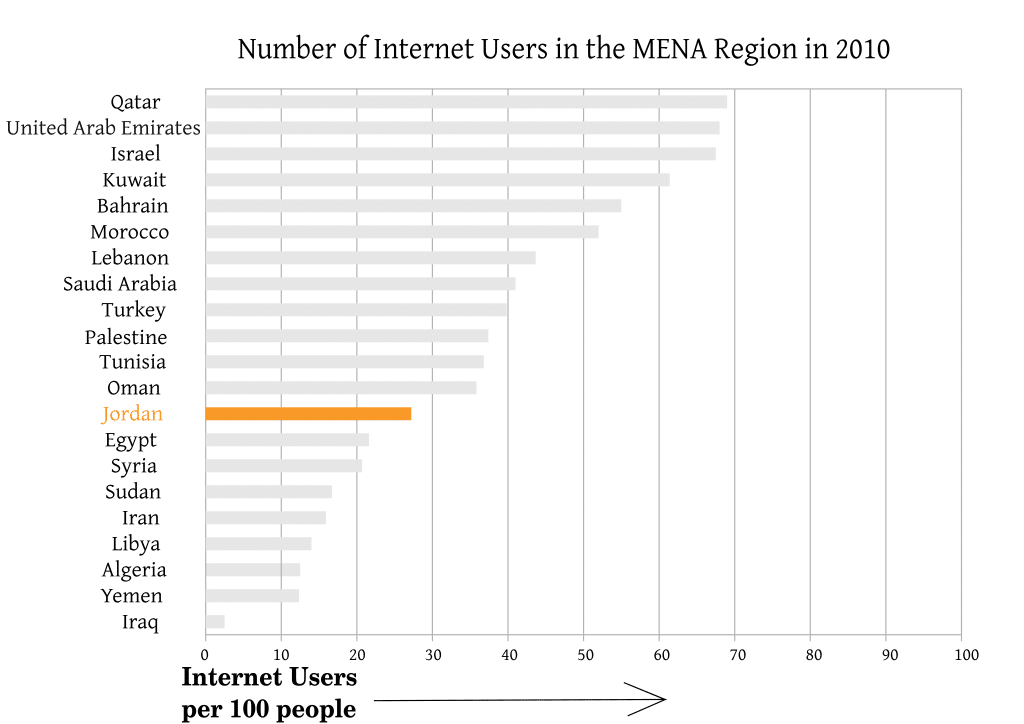

The growth of internet access and use in the country since its introduction in 1995 has allowed for a greater degree of online independence and criticism. However, cybercrime legislation is enforced to ensure that only moderate criticism is tolerated by King Abdullah across the media.

Freedom of Expression

The modern-day media environment in Jordan is highly government-influenced and is not conducive to freedom of expression. The country ranks 135th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2016 World Press Freedom Index.

Article 15 of the Jordanian Constitution of 1952 guarantees freedom of expression but crucially within the overriding jurisdiction of the law: ’Every Jordanian shall be free to express his opinion by speech, in writing, or by means of photographic representation and other forms of expression, provided that such does not violate the law.’

Legal obstructions to this freedom include the 2011 criminalization of reporting on corruption without ‘sufficient evidence’, and the 1998 Press and Publications Law that issues substantial fines against those found guilty of insulting the royal family or religion, or advocating practices contrary to the nation’s values. A 2010 amendment to this law referred press violations to specialized criminal courts.

Jordan has issued further legislation in recent years to impose control over online media. A 2012 addition to the Press and Publications Law required online news websites to obtain a government license, and applied the law’s content restrictions to online publications. The government retains the capacity, without a court order, to block foreign or domestic websites that do not comply with this legislation, and nearly 300 websites were blocked in 2013 alone.

The 2010 Cybercrime Law prohibits the online publication of information pertaining to national security or foreign affairs that has not already been made publicly available. Amendments in 2014 to the country’s anti-terror legislation expand the legal definition of terrorism to include jeopardizing Jordan’s relations with neighbouring states, and outlaw the use of mobile technology to promote or support ‘terrorist’ acts.

In 2015, the hierarchy of Jordan’s contradictory web of media laws was exposed when cybercrime legislation overrode the press law’s ban on imposing jail sentences for media offences.

Tareq Abu al-Ragheb, a news anchor for privately-owned satellite channel al-Haqiqah, was arrested for a Facebook post deemed ’insulting to religion’ and threatening Jordanian citizens ’co-existence’. Al-Ragheb was charged under cybercrime legislation, leading to his imprisonment, although he was released after a week.

In the same year, Jamal Ayoub wrote an article criticizing Saudi Arabia’s airstrike campaign on Yemen, which was published by Osama Ramini and Hassan Safirah on the al-Balad news website. All three were sentenced under anti-terror legislation for ’insulting a foreign state’, with Ayoub jailed for four months and Ramini and Safirah sentenced to three.

In December 2015, Islamist commentator Iyad Qunaibi was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, later reduced to one year, for publishing Facebook posts criticizing what he considered to be un-Islamic aspects of Jordanian society.

Television

The BBC observes that television in 2016 was overwhelmingly the most popular news source among Jordanians. This reflects the findings of a 2011 survey conducted by Ipsos, which revealed that 82 per cent of Jordanians consumed news primarily via television.

However, with a satellite penetration rate of over 90 per cent, the majority of viewers opt for pan-Arab channels such as al-Jazeera, al-Arabiya, MBC and LBC. The most popular domestic television channels are as follows:

JRTV – The state-owned broadcast network was established in 1985. In 2001, it underwent a significant restructuring process resulting in a primary channel, a dedicated sports channel and a third devoted to movies and children’s programming. JRTV also broadcasts internationally via the Jordan Satellite Channel.

ATV – Jordan’s first independent television channel was initially scheduled to begin broadcasting in 2007, but it was hampered by a series of administrative delays. It was initially conceived as a news channel but was sold in 2008 to the Arab Telemedia Group, which specialized in drama productions. The channel never aired after initial test broadcasts.

Al-Roya TV – Established in 2011 in Amman as an independent satellite channel focusing on entertainment programming, with occasional news coverage and talk shows.

Radio

Radio is the second most popular news source for Jordanians, according to a 2011 Ipsos survey. Unlike the domestic television environment, dozens of private radio stations have emerged following the 2003 Audio Visual Law. However, UNESCO has recently raised concern about the trend of media concentration within Jordan’s privately-owned radio environment.

Of the 24 privately-licensed channels, four companies are responsible for 12 of them. The New York Times reports that prior to the 2011 Arab uprisings, the majority of Jordanian radio stations aired music, however an increasing number are beginning to discuss political issues. A selection of the country’s most notable stations includes:

Radio Jordan – State-owned channel established in Amman in 1959. It airs 24-hour news and current affairs programming in Arabic and English, reporting from a pro-government perspective.

Rotana FM – Launched in 2005 as part of the pan-Arab Rotana conglomerate, airing music and entertainment programming. It is believed to have the highest listenership of all stations in the country.

Fann FM – Established in 2003 and part-owned by the Jordanian armed forces, Fann FM predominantly broadcasts local music but also phone-in shows to discuss local political topics.

The state broadcaster JRTV also operates the music-basedAmman FM and sports-orientated Hadaf FM, in addition to the highly-popular al-Qur’an al-Karim, a station dedicated to Koran recitals.

Press

The 2011 Ipsos survey mentioned above reports that only 3 per cent of Jordanians primarily access the news via newspapers, with the industry suffering from years of government-imposed restrictions. The most popular domestic publications are as follows:

Al-Rai – Founded in 1971 and owned by the Jordan Press Foundation (JPF), in which the government holds a 60 per cent controlling stake. It has therefore maintained a largely pro-government stance throughout its publication but has staged protests in recent years, including a one-day halt in publication in 2013 for the first time in its history, to protest excessive editorial intervention by the Jordanian prime minister. The Oxford Business Group classifies al-Rai as the most-read Jordanian daily. The JPF also publishes Jordan’s only English-language daily as its sister newspaper, The Jordan Times, which attracts a sizable audience, particularly online.

Ad-Dustour – Established in 1967 as the result of a merger between two newspapers published in the West Bank, Filastin and al-Manar, with publication moved to Amman as a result of the Six Day War that year. It initially operated in a private capacity, but the Jordanian government has steadily increased its share. Freedom of expression NGO Article 19 observes that the majority of its content focuses on the royal family and government announcements.

Al-Ghad– Established in 2003 by Mohammad Alayyan and the private Al Faridah for Specialized Publications, Al-Ghad is described by the Oxford Business Group as ’Jordan’s first major independent newspaper’. Although free from government editorial control, the newspaper nonetheless practices self-censorship, refusing to publish an article by a prominent writer in 2014 criticizing King Abdullah’s ’consolidation’ of power.

Al-Arab al-Yawm – Founded in 1997 with an initial reputation for independent and investigative reporting, the paper quickly came under the scrutiny of the Jordanian authorities and its subsequent lawsuits. The newspaper was sold to a government subsidiary in 2000, and has since adopted a far more pro-government stance.

Assabeel – Founded as a weekly publication in 1993 by Muslim Brotherhood supporters seeking to take advantage of Jordan’s political and media liberalization measures. It became a daily publication in 2009.

Press

Social media has been steadily adopted by citizens and government officials alike. Queen Rania has been particularly adept at amassing the largest social media following of any Jordanian, with over 5.9 million Twitter followers and 2.8 million Instagram followers.

Her Facebook page has more ’likes’ (10.6 million) than Jordan’s total population, indicating her widespread social media appeal.

In light of its evident popularity in the kingdom, Jordanian authorities are keeping a close eye on social media.

In 2016, the Jordanian government admitted to monitoring social media and warned that ’anyone found to be inciting hate speech or sectarianism will be referred to the concerned authorities for further legal prosecution’.

In the same year, the government also demonstrated its complete control over internet communication by implementing a nationwide shutdown of WhatsApp, Instagram and Viber for two hours, during which secondary students sat their final exams.

| Platform | Percentage of respondents who use it |

| 89% | |

| 71% | |

| YouTube | 66% |

| Google + | 43% |

| 34% | |

| 33% |

Table 1. Most popular social media platforms among Jordanians in 2015. Source: 2015 Arab Social Media Report, issued by Dubai School of Governance

Online Publications

As outlined earlier, the Jordanian government’s requirement that online news websites register for a license or face being shut down means that many of the more outspoken online publications have been forced out of operation. Yet the internet has nevertheless offered a greater degree of independence to the Jordanian media environment. A selection of the most popular online news websites are as follows:

Ammon News – Established in 2006 as the country’s first online newspaper. It describes itself as the ’voice of the silent majority’ and has become one of the most popular news platforms in the country, offering news content in English and Arabic. In 2011, it was hacked after publishing a statement by 36 Jordanian tribal figures calling for economic and political reform in the country, which Jordanian security forces had asked to be removed.

Khaberni – Founded in 2008 as an online news portal. It was one of the first online publications to embrace mobile technology and also has an established YouTube channel that airs interviews with citizens as well as footage of demonstrations.

Saraya – Another highly popular news website – believed to be in the top 20 most-visited Jordanian websites in 2012, along with Ammon News and Khaberni, according to an Ipsos survey. Saraya was initially blocked in 2013, after failing to comply with the government’s online registration laws, but subsequently received its license. In 2015, two of its editors were arrested by Jordanian security forces for allegedly reporting false information about a prisoner exchange between Islamic State and the government.

Jafra News – Online news publication that has garnered a sizeable audience. In 2013, its editor-in-chief Amjad Muala and publisher Nidhal al-Faraneh were arrested for posting a video depicting a Qatari prince dancing and showering with numerous women. Muala and al-Fareneh were charged with damaging Jordan’s relations with a foreign state.

The internet has also given rise to online broadcasting in Jordan. In 2000, AmmanNet was established as the Arab world’s first online radio station. The station hosts talk shows and profiles political candidates and new laws. In 2015, al-Balad was established as an online community radio channel, dedicated to social and cultural discussion.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Jordan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: