State Borders

For centuries the region that forms the present-day Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan was part of Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria). It is the land called by geographers Transjordan, meaning the region across the River Jordan (as viewed from imperial Great Britain), including its East Bank. It occupies an area of approximately 90,000 square kilometres. In 1921 the Emirate of Transjordan came into existence under British rule (mandate), and in 1946 Transjordan became independent and was named the Kingdom of Transjordan.

During the 1948-1949 war between Israel and several Arab states the Jordanian armed forces – and some Iraqi forces – occupied the West Bank (including the Old City of Jerusalem), an area of about 5,500 square kilometres. The West Bank was annexed in 1951, and the name of the Kingdom was changed to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

Until the 1967 June War the West Bank was part of Jordan. During that war it was conquered by Israel and has remained in Israeli hands ever since. After a series of failed attempts to restore Jordan’s control over the area, King Husayn in 1988 – one year after the outbreak of the First Intifada – decided to give up all claims to the West Bank and sever all administrative and legal ties with the area that had been maintained since 1967. Jordan was thereby formally returned to its original size.

Jordan is bounded on the north by Syria, on the east by Iraq, on the south-east and south by Saudi Arabia, and on the west by the Occupied Palestinian West Bank and Israel. Jordan’s only access to the sea is the eight-kilometre-wide strip on the Gulf of Aqaba, at the country’s south-western tip. In 1965 this strip was expanded southward to about 26 kilometres by a special boundary-adjustment agreement with Saudi Arabia.

Geography and Climate

Much of Jordan is barren desert. The north-western part of the country is part of the so-called Fertile Crescent. The other fertile area consists of the highlands forming the eastern edge of the Jordan Valley.

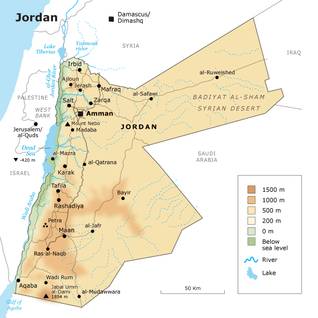

Jordan consists of three natural regions: the Jordan Valley (Ghor al-Urdunn or al-Ghor); the highlands bordering the eastern edge of the Jordan Valley; and the plateau of the Syro-Arabian desert, which slopes gently to the south and east.

Climate

Jordan has a long, hot, dry summer, usually extending from May to November, and a cold winter, usually from December to February. Rain falls only during the winter months and is barely adequate for the country’s needs. The climate is generally of the Mediterranean type, but that applies mainly to the higher lands. Further east, towards the desert, it is hotter during the day and cooler at night. It is also very hot in the Jordan Valley and on the Gulf of Aqaba during the summer months and pleasantly warm there in winter.

Precipitation varies by region. Most of the East Bank – the desert portion – receives little rain, less than 120 millimetres annually. Precipitation increases on the highlands, where it reaches 500 millimetres in the north and 300 millimetres in the south. The Jordan Valley receives more rain in the north (300 millimetres annually) than in the south (120 millimetres).

The daytime temperature averages about 33 °C during summer but sometimes exceeds 40 °C. It is always hotter in the Jordan Valley, Aqaba, and the desert. It is pleasant in the hilly areas at night, where it is often dry and comfortably cool. Jordanian winters are cold, and snow falls in some years. While the average daytime temperature in winter is about 13°C, it often drops to zero or below, especially at night, with the formation of frost.

The weather patterns are changing noticeably. Rain is less evenly distributed, and the range of temperature extremes is widening.

Topography

Highlands

The highlands, which make up most of Jordan, are divided, north to south, into three parts. Sawad al-Urdunn, ‘the arable land of the [River] Jordan’, lies between two tributaries to the River Jordan, the Yarmouk, to the north, and the Zarqa, further south. Irbid, the second largest city in Jordan, after the capital, and Ajloun, with its neighbouring forested highlands, are the main urban centres in this area.

The central portion is Balqa Heights, containing Amman and the major towns of Salt and Madaba. This region stretches from the Zarqa River in the north to the gorge called the Mujib Valley (Wadi al-Mujib), in the south. The Mujib River, actually just a stream, drains into the Dead Sea. This area is fertile and is now densely populated and highly developed.

The third, southernmost part, Bilad al-Sharat or Jibal al-Sharat, consists of higher hills, the highest reaching 1,200 metres above sea level in the north and 1,854 metres in the south, at Jabal Umm al-Dami. Karak, with its famous crusader castle, is the main city in this region; it overlooks the southern end of the Dead Sea.

Desert Plateau

Almost three quarters of the area of modern Jordan consists mainly of a barren plateau, which is an extension of the Syrian Desert. Its sand-and-gravel plains stretch east to the Iraqi border, south to the Saudi Arabian border, and north to the Syrian border.

Important cities, including Maan and Aqaba, are situated there. This region is mainly arid, except for Azraq (60 kilometres east-south-east of Amman), its only major oasis, which is currently drying out.

Bedouins throughout history roamed the desert seeking pasture for their herds. Large tribes inhabited areas straddling international borders, and, until those borders began to be controlled, they crossed them at will, as economic and social requirements dictated.

al-Ghor

Al-Ghor, Arabic for ‘the depression’, refers to the Rift Valley (including the Jordan Valley). It runs from north to south, following the course of the River Jordan. It descends from an elevation of 1,500 metres on the Golan Heights, to about 200 metres below sea level at Lake Tiberias to about 423 metres below sea-level at the Dead Sea, which receives the little water remaining these days in the River Jordan.

The Dead Sea’s surface is the lowest point on earth’s land surface, and it continues to fall as the Dead Sea itself shrinks steadily as a result of diminished water supply from the streams that used to replenish the water lost by high evaporation in the very hot depression. The area extending from the southern tip of the Dead Sea to the port city of Aqaba on the Gulf of Aqaba is known as the Wadi Araba (Araba Valley).

The first, short part of the wadi just south of the Dead Sea, is known in Jordan as al-Ghor al-Safi (the pure lowland). Because that area is irrigated, it is a productive small-scale source of vegetables and citrus fruit.

The elevation of the Wadi Araba rises toward the south, from the level of the Dead Sea surface to about 300 metres above sea level before falling gradually again until it reaches the Red Sea, at the Gulf of Aqaba. Except for that short fertile stretch, the Wadi Araba is mostly a sand-and-gravel desert. The term araba seems originally to have been a Canaanite and Aramaic word meaning ‘steppe’ or ‘desert’.

The fertility of the northern section of al-Ghor is due to the alluvial soil and warm or hot weather year round and to its irrigation by water from the ever-shrinking River Jordan and its tributaries and from aquifers (underground layers of water-bearing permeable rock).

The Jordan Valley supplies Jordan with most of its vegetables, with some excess for export. Al-Ghor is also famous for its high-quality citrus fruits, bananas, melons, cucumbers, tomatoes, and aubergine. Although the only inhabitants of the Jordan Valley were, for centuries, local farmers and Bedouins, the valley has, since Ottoman days, been a winter resort for wealthy people who maintain farms and holiday residences there.

Fashionable hotels and a huge conference centre have been built on the eastern shores of the Dead Sea, and many major conferences are held there. Despite the intense heat in the summer months the valley is now attractive to tourists in summer as well as winter. The water of the Dead Sea contains various minerals that have been scientifically proven to help cure many dermatological problems.

Only the eastern part of the Jordan Valley belongs to Jordan. Israel and the would-be Palestinian state lie on the western side. The Dead Sea is also divided mainly between Jordan and Israel.

Natural Resources

Jordan is generally a resource-poor country. It does, however, contain significant deposits of phosphates, uranium, and oil shale, as well as some potassium, salt, natural gas, and stone.

Phosphate mines in the south make Jordan one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of this mineral. Phosphates are transported by rail from the mines to the port of Aqaba, where it is shipped overseas. Potential Jordanian sources of energy have been the focus of renewed interest in recent years. Jordan’s uranium reserves are large, accounting for 2 percent of the world’s total. It is estimated that Jordan can extract 80,000 tonnes of uranium from its uranium ores, and the country’s phosphate reserves contain some 100,000 tonnes of uranium. There are plans to build several nuclear plants to meet Jordan’s growing electricity demand, but these seem still to be in an early stage of development.

Natural gas was discovered in Jordan in 1987. Reserves are estimated at 230 billion cubic feet. The Risha field, in the Eastern Desert near the Iraqi border, supplies a nearby power plant with nearly 30 million cubic feet of gas a day.

Oil Shale

It is believed that the huge quantities of oil shale that exist in the central and northern regions of the country – Jordan’s oil-shale reserves are estimated by the World Energy Council to amount to 40 billion tonnes, the second largest after Canada – are still not commercially viable, but they could be exploited at some point, if oil prices continue to rise. Jordan recently signed an agreement with Royal Dutch Shell to extract and exploit shale-oil in central Jordan.

It is expected that Jordan will produce its first commercial quantities of oil in the year 2020, with an estimated production of 50,000 barrels of oil a day, and 35 percent of the Kingdom’s energy consumption in ‘less than 10 years’. Previous studies have estimated 40 billion tonnes of oil shale in 21 sites, concentrated near the Yarmouk River, Buweida, Beit Ras, Ruwaished, Karak, Madaba, and Maan. A switch to power plants fuelled by shale oil has the potential to reduce Jordan’s energy bill by at least 40-50 percent, according to the National Electric Power Company.

Water is a serious problem: Jordan is one of the most water-scarce countries in the world. Water is needed not only for irrigation and for increasing domestic use but also for the utilization of some resources, such as oil shale, and for various other industrial activities. Jordan is presently considering building a nuclear reactor for power generation, and such a plant would require huge amounts of cooling water.

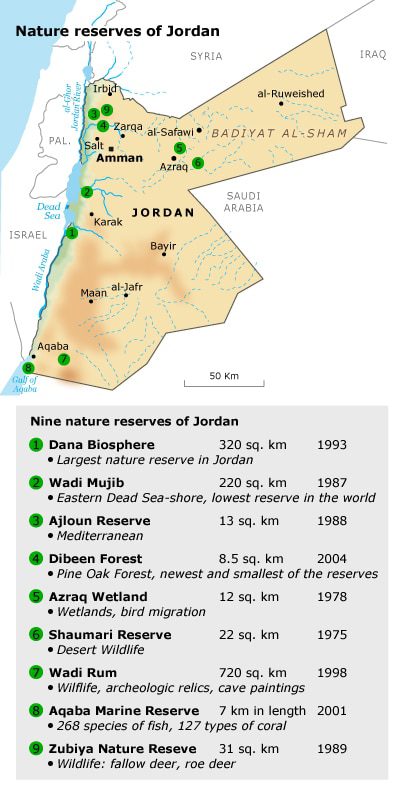

Nature Reserves

There are at least nine nature reserves in Jordan. The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN), which first suggested natural reserves and then established them, was founded in 1966. Its first task was the re-establishment and protection of endangered species. The RSCN was given the right to issue hunting licenses in 1973.

This was essential to its mission, which mandated that it must first tackle the problem of uncontrolled hunting, which contributed in large part to extinctions and the destruction of natural habitats. The Shaumari Reserve was founded in 1975, in order to enable the breeding of endangered species, specifically the Arabian oryx, gazelles, ostriches, and Persian onagers.

In 1989 the Dana Biosphere Reserve, which is Jordan’s largest nature reserve (circa 320 square kilometres), was founded in and around Dana village and Wadi Dana, in south-central Jordan.

In 1994, the RSCN began its survey programme, run by experienced researchers. The primary purpose of the programme was to collect the information required to create suitable and sustainable habitats for wild animals, through scientific experimentation and research. A business branch of the RSCN, tasked with running socio-economic projects, was established later.

An RSCN training programme established in 1999 aims to build regional and local skills in nature conservation. The Save Jordan’s Trees campaign was started in 2005, to make the Jordanian people aware of the value of trees in nature.

The latest Jordanian nature reserve was created in Dibeen in 2004 and covers an area of 8.5 square kilometres. Nine additional nature reserves have been proposed, as well as two other sites that are possible candidates for preservation.

A map of the nature reserves in Jordan in 2012 is displayed on the right of this page.

Environment

Jordan ranked 117th in the 2012 Environmental Performance Index, a study that ranked 132 countries on environmental public health and ecosystem vitality.

The kingdom has only begun, over the past decade, to pay more attention to environmental issues and the protection of the environment. The Ministry of Environment was established in 2003 and began studies of the most prominent environmental issues the country faces and ways to deal with them. Among Jordan’s most important environmental difficulties are the shortage of water, soil erosion, and air pollution.

The Ministry identified environmental hot-spots, mainly polluted areas, among them the cities of Russeifa, which is polluted by phosphate mining in the nearby hills, and Zarqa, which lies in the Sayl al-Zarqa watershed. The ministry has been working over the past two years to rehabilitate the Zarqa, which has been polluted for years, and to create a a community of craftspeople in the city of Russeifa.

Jordan was, in 2006, one of the first countries in the Middle East to create an environmental or ‘eco’ police force to inspect industrial zones and recreational areas. The force operates under eighteen laws created to protect the environment. It has carried out inspections of chemical and industrial factories to ensure that they abide by environmental rules and regulations.

In late 2010 the Ministry established an environmental directorate in the governorate of Ajloun to safeguard its bountiful forests. Violators are jailed for three months and fined.

Beginning in the summer of 2011, the government will move chemical and medical wastes to special units to ensure that they are disposed of properly. In the past two years, the country has switched completely to unleaded petrol, which is available in 90- and 95-octane grades, and efforts are being made to improve the quality of diesel fuel.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Geography’ and ‘Jordan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: