Introduction

Jordan’s society has changed substantially over the past decades. Communities have grown larger, especially in the urban areas and particularly in Amman, where most jobs are located. The population has increased, fed by immigration from neighbouring countries. Increased poverty has raised crime rates throughout the kingdom. The government has taken measures to protect families, especially to preserve the rights of children and women. Women take part in the political life of the nation, as members of parliament and in various ministries. Young people today are more aware of their rights and are more politicized. The online media are playing a more important role in everyday life and have become a platform on which people from various walks of life can express their views.

Human Development Index

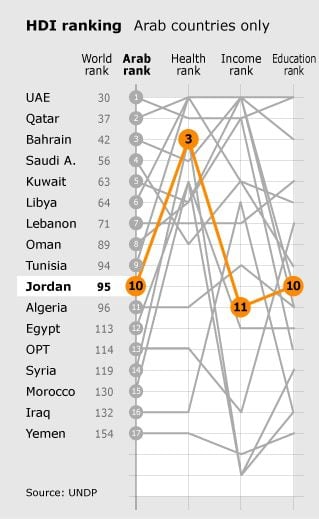

In 2011 Jordan ranked 95 out of 187 countries and areas in the UNDP’s annual Human Development Index (HDI), which measures the well-being of nations and includes three basic components of human development: health, education, and income. Over the years, particularly since 1980, Jordan’s HDI increased from 0.5 to 0.7, placing it at the top of the ‘medium’ category.

Jordan exceeded the average of the rest of the Arab world, which increased from 0.4 in 1980 to 0.64 in 2011. Between 1980 and 2011, Jordan’s life expectancy at birth increased by more than six years; the average number of years of education increased by about three. The country’s per capita gross national income rose from USD 3,980 to USD 5,300 (using purchasing power parity rates).

In 1995, the HDI introduced a new measure, the Gender Inequality Index, which reflects the deficits of women in three areas – reproductive health, empowerment, and economic activity. Based on the 2011 data, Jordan’s ranking was 83 out of 187 countries in gender inequality. Female participation in the labour market was 23 percent in 2009, compared to 73 percent for men.

In 2010, 57 percent of adult women aged 25 or older have a secondary or higher level of education compared to 74 percent for men. In 2008, for every 100,000 live births, 59 women die of pregnancy-related causes. The adolescent fertility rate was 26.5 births per 1,000 live births.

Also introduced in that report was the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which identifies multiple deprivations in the same household in education, health, and standard of living. In Jordan, 2.4 percent of the population suffers from multiple deprivations, while an additional 1.3 percent are vulnerable to multiple deprivations. In 2009, Jordan’s MPI was 0.008.

Clans and Communities

Tribes still play a significant role in Jordanian society. The overriding demographic division is between East Bank Jordanians and Jordanians of Palestinian origin, all of whom ended up living in the East Bank, along with other ethnic minorities.

Historically, tribes came to the kingdom from around the region and settled there for various reasons. Jordan has always been a route for Arab migrations from al-Jazira (Saudi Arabia) to Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria). Migrating tribes would settle for a time in southern Jordan before moving north to Syria, through Wadi Araba to Palestine, or through the Sinai to Egypt and then North Africa. Members of tribes might stay behind in Jordanian lands, while some of the tribes returned from Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon to settle in Jordan, retaining only the memory of their ancestral lands. Most of Jordan’s tribes immigrated from the south; only rarely did tribes come to Jordan from Iraq through Syria.

Many of the tribes returned to Jordan during the latter days of the Ottoman Empire, to work in trade or agriculture, to return to their mother tribe for protection, or for other reasons. Many Christian tribes fled southern Syria after clashes with other tribes; other (Druze) tribes arrived after the Syrian revolution against the French.

The tribes have always been considered the backbone of the Jordanian monarchy. They have demonstrated their unlimited loyalty to the King, pledging to protect the monarchy and prevent any action aimed at disrupting the country’s political balance.

Jordanians of Palestinian origin who fled their land during the wars of 1948 and 1967 and the 1991 Gulf War make up more than half of the population in the kingdom. They play an important role in Jordan’s social, political, and economic life. According to UNRWA, which aids Palestinian refugees in the region, Jordan hosts over two million registered refugees from the Palestinian territories.

Imbalances

Although a small country with limited natural resources, Jordan took in the most Palestinian refugees in 1948-1949 and 1967. UNRWA estimates the number of registered Palestinian refugees at more than 2 million, most of whom have the Jordanian nationality, the exception being 140,000 who are originally from the Gaza Strip, which was administered by Egypt until 1967; they carry only temporary passports and are not full citizens.

Jordanian officials have, on several occasions, expressed fears that Jordan might be considered an alternative homeland for the Palestinians and began to revoke the nationality of some Jordanians of Palestinian origin. They explained that these measures were meant to guarantee the Palestinians’ right to return to their homeland by renewing permits that recognize them as citizens in the West Bank.

They also said that Jordan was attempting to implement a 1988 administrative decision that severed legal and administrative ties with the West Bank, a decision that was taken during the 1974 summit in Rabat, in order to allow the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) to act as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.

In February 2010, Human Rights Watch (HRW) warned Jordanian authorities against revoking the citizenship of these people. The human-rights watchdog said that the Jordanian authorities stripped more than 2,700 people of their nationality between 2004 and 2008, and the practice continued in 2009.

HRW said that the move was not based on a transparent regulation and that, by rescinding their citizenship, the authorities were denying these people the basic rights of citizenship, including access to education and health care, finding work, travelling, and owning property (see also the HRW report Stateless Again).

More recently, Jordan received another wave of refugees, this time from Iraq, after the American-led war on Iraq in 2003. In 2007, the Norway-based social-science research institute FAFO, in cooperation with the Jordanian Department of Statistics, surveyed Iraqis in the kingdom, concluding that in May 2007 there were between 450,000 and 500,000 Iraqis in Jordan.

This imposed a heavy burden on the fragile economy of Jordan. Since then, many Iraqi refugees have moved to a third country with the help of the UNHCR, while others, in better financial condition, remained in the kingdom, starting their own businesses and buying property in Amman.

Crime

Jordan is considered relatively peaceful, although there has been concern in recent years over the increasing crime rate. Public Security Directorate statistics show that the number of recorded crimes in the kingdom increased by 4.5 percent from 2008 to 2009. A police spokesman asserted that the increase was within the ‘natural’ range expected of a developing country with a rapidly growing population and that the rate of crime detection was among the highest worldwide.

A recent report on crimes and civil unrest in the kingdom (OSAC Jordan 2011 Crime and Safety Report) showed that the overall crime rate remained low in 2010 and early 2011. The report found that economic factors, clan disputes, and the parliamentary elections of November 2010 played a role in civil disputes in the kingdom and the increasingly frequent demonstrations in several governorates.

The Public Security Directorate has stressed that Jordan is a transit point for drug trafficking in the region but that the rate of drug use among Jordanians is relatively low. Although the Directorate believes that drug trafficking is rising, despite efforts at control, statistics show that the total number of drug cases in the country and the number of substance abusers decreased slightly from 2009 to 2010.

The report also commended the Public Security Directorate for its professionality and called it one of the most effective in the region, because of the training it receives from the United States. It said that the Directorate is capable of maintaining security in hotels and areas where international diplomats and businessmen reside and that police response-time in the capital is three to five minutes; the capital has a 24-hour emergency-control centre.

Jordanians have, however, been dismayed over the past couple of years at the increase in civil unrest in their country, particularly inter-tribal feuds and attacks on policemen.

Family

Jordan’s society is centred on the patriarchal extended family, which includes not only the nuclear family (parents and siblings) but also more distant relatives by kinship and marriage and members of the same tribe or clan. Although this focus has become less prominent in recent years, especially in larger cities, for financial and social reasons, many Jordanians are still strongly family-oriented.

People rely on relatives, even distant ones, financially and socially, in what is known as wasta (mediation by people on behalf of others to whom they are connected by friendship or blood), for obtaining jobs or advancing other personal interests, and for social connections, protection, and emotional support.

Most Jordanians still respect and follow traditional social customs in their daily lives, as in marriage, death, and the care of elderly parents. Men and women remain in their family homes until they marry, not only for financial reasons but also for traditional and religious reasons. Only students who study in universities far from their families’ homes live on their own, usually in dormitories.

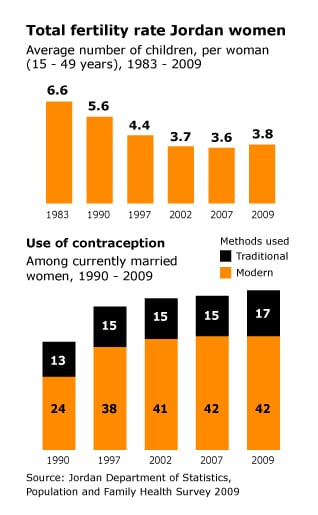

In the first decade of the century, family planning was stressed, and Jordanian families began to accept the idea. However, World Bank statistics show that the fertility rate (the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime) remained stable at 3.8 from 2007 until 2010.

According to the 2009 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS), Jordan has succeeding in increasing the use of modern family-planning methods among married women aged 15-49 from 27 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2009.

Women

Jordan has made strides in women’s empowerment issues, although pressure groups demand the amendment of laws guaranteeing women’s rights. Jordanian women hold senior governmental posts, including ministerial positions, and often run their own businesses.

A special quota system was introduced in 2003 to ensure that women will play a role in Parliament, guaranteeing them a minimum of six seats. Last year the number of seats was increased to twelve, and, during the sixteenth parliamentary elections in November 2010, thirteen women were elected, twelve through the women’s quota and one through direct competition in Amman.

Women’s education has been given much attention, and many gains have been made in providing equal learning opportunities for girls; school enrolment of girls between the ages of 6 and 15 was 97.7 percent in 2008-2009.

The Jordanian National Commission for Women recently presented to the Parliament a 29-page statement demanding legal reforms to achieve justice and equal opportunities for men and women. The statement commended the country’s investment in women’s education and training but said that, unless women are given equal rights as citizens and their constitutional and human rights are respected, their gains will not be maintained.

They asserted that certain laws needed amendment, including that the elections law should guarantee that 30 percent of the total parliamentary seats be allocated to women, whereas the current quota reserves just twelve seats for them, out of a total of 120. They also called for amendment of the citizenship law to allow Jordanian women to pass their nationality on to their children, to allow non-Jordanian women married to Jordanians to obtain citizenship within a certain period, and to allow Jordanian women married to non-Jordanian men to reclaim their Jordanian nationality at will.

They also asked that, under the residency law, the non-Jordanian husband and children of a Jordanian woman be automatically granted residency in the kingdom. They also demanded additions to the 2010 personal-status law – for instance, to allow joint custody after divorce, to increase the minimum age at which females are permitted to marry, and to allow women to file for divorce without providing justifications.

Youth

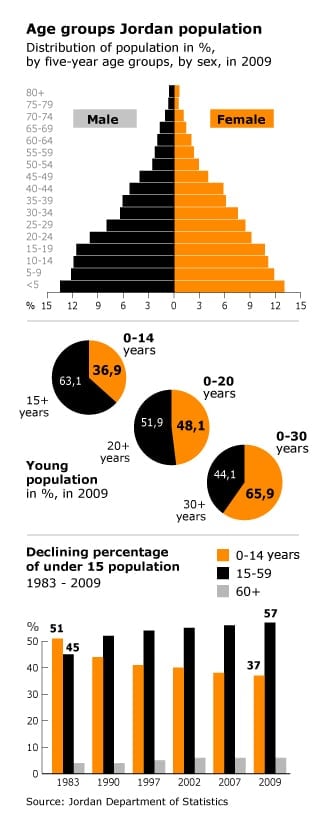

Jordan is a young country: 70 percent of its population is under the age of 30. In a country with scarce natural resources, people – especially young people, who are the largest segment of society – are its greatest asset. But opportunities for young people in the kingdom are scarce, and they face a high unemployment rate, which, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), reached 30 percent in their age group (2004).

Today, young Jordanians also play a more important political role. Weekly demonstrations calling for reforms and stricter measures to fight corruption are dominated by new youth movements, such as the Jayeen (We Are Coming) organization, which includes young people from various backgrounds that have taken to the streets demanding reform. March 24 is a youth group that calls for reforms and democracy while safeguarding national unity; it has organized many sit-ins and demonstrations.

Many national and international organizations are working on programs to improve the status of young people and provide them a better future. Save the Children, which has been operating in the kingdom since 1985, has worked with Jordanians in several youth programs focusing on civic action.

Save the Children helped establish many programs, including Injaz (Achievement), which has reached more than fifty thousand students between the ages of 21 and 24 each year since its founding in 1999, with the aim of familiarizing them with the job market and building their skills before they begin looking for jobs.

The Najah (Success) Program provides Jordanian youth between the ages of 18 and 24 with career counselling and support to help them stay employed, and it aims to increase parental support for youth employment and entrepreneurship.

The UNDP in 2010 assisted Jordan’s Higher Council for Youth in formulating the second phase of a five-year national strategy (2011-2015) that will train young people in the twelve governorates in leadership skills; help raise their awareness about civil rights and citizenship; encourage them to take part in decision-making, political parties, and local development; and help with the formation of youth councils.

Education

Jordan has introduced education reforms designed to invest in the country’s youth, who form the majority of the population. It has improved school buildings and transformed education programs. Ministry of Education statistics for 2009-2010 show that Jordan has 3,371 public schools, 2,140 private schools, and 174 UNRWA schools (for Palestinian refugees). UNICEF statistics show that the literacy rate for young people (15-24 years) was 99 percent between 2005 and 2010.

In its report Education Strategy 2006, the ministry said that some Jordanian families, especially lower-income households, still do not believe that early learning is as important as higher-level education; this attitude arises from their lack of awareness, the small number of kindergartens, and the high cost of enrolling children in these centres.

Public figures show that about 20 percent of GDP is spent on education. Jordan’s government has evaluated all of its development strategies, including that for education. This has focused the authorities’ attention on the need to reorient the educational system and improve its quality, efficiency, and equity.

With the help of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the government designed a comprehensive education strategy to, among other things, improve teachers’ qualifications to offer education appropriate to the knowledge economy, upgrade public schools, and provide equal access to pre-school.

The Education Reform for the Knowledge Economy (ERfKE) achieved most of its targets, including 164 education-reform projects programs; 85,000 teachers trained on International Children’s Digital Library software; 942,000 students benefiting from improved school buildings; 2,822 schools connected to online-learning portals; 84 percent of primary and secondary students using online-learning portals; 87 percent of students having access to safe and adequate primary and secondary education facilities; and 52 percent enrolment in the second level of Kindergarten (pre primary school), compared to 41 percent in 2003.

About 80 percent of Jordan’s schools are connected to the Internet; 93 percent of Kindergarten teachers have been trained on the University of Wisconsin program Working With Young Children; there has been a 37-percent increase in qualified Kindergarten teachers with bachelor’s degrees and certification; there has been a 46-percent increase in fully equipped Kindergartens; and 29 percent of teachers now use the Internet, an increase of 15 percent from 2004.

Health

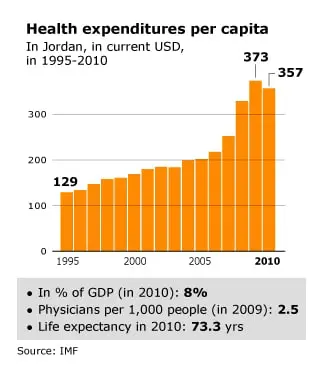

Jordan has an advanced health-care system, and the sector has continued to develop during the past two decades. UNICEF’s statistics for 2010 show that the infant-mortality rate (under 1) was 18 per thousand live births, compared to 32 in 1990, while life expectancy (years) at birth was 73.

The World Health Organization (WHO) indicators for 2009 show that the kingdom’s expenditure on health was 9.3 percent of total GDP, and the Ministry of Health budget was 11.3 percent of the total government budget in 2009. The government provides, at nominal cost, health services to the underprivileged in its 32 public hospitals and health centres; cancer treatment is free.

USAID has been the main donor in the health sector, helping Jordan upgrade its health services by funding several projects, including improving its primary-health centres – approximately 380 in the 12 governorates – by refurbishing and re-equipping them, and by promoting a healthy lifestyle among Jordanians.

Jordan has been promoting itself as a regional medical hub, where other Arabs can come for treatment: it is a top health-care destination for many Arabs, especially from Yemen, Algeria, and Libya. Petra News Agency said that revenues from medical tourism reached more than USD 1 billion in 2010, and the number of patients reached 220,000. In a 2008 study, the World Bank ranked Jordan as the leading medical destination in the region and the fifth-ranked such destination in the world.

The unrest that swept through Arab countries since the beginning of 2011 has, however, caused the number of Arab patients to plummet, resulting in a 90-percent drop in Libyan patients, 60-percent in Syrians, and 50-percent in Yemenis and Bahrainis.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Jordan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Protection

Jordan has taken many measures over the past two decades to protect women and children and prevent domestic violence and physical and sexual abuse. One such measure was the establishment of the Family Protection Department in 1998.

The department receives complaints directly from victims or their parents via the toll-free telephone number 911 or by email or a special form on the department’s website. They also receive reports through police stations, other governmental institutions, and non-governmental organizations.

Once complaints are received, specially trained officers conduct recorded interviews with victims that can be used later to present the case in court. Victims undergo medical examinations by specialists from the National Institute for Forensic Medicine. In order to spare victims further emotional distress, the medical examinations are carried out in the department itself rather than in a hospital, unless the victim needs further medical assistance and care.

Psychological follow-ups are available for some victims. The department, in cooperation with the Ministry of Social Development and the Jordan River Foundation, makes visits to follow up on certain cases, and some cases are transferred to social-support centres.

In 2001 the National Council for Family Affairs was established as a national-policy think tank and as a monitoring and advocacy body for family issues. In late 2008, the Public Security Director established a regional training centre to provide training on family protection.

Hani Jahshan, an international expert in combating violence, said that 2,137 cases of sexual abuse and domestic violence were seen at the National Institute for Forensic Medicine in 2010. 36 percent of these cases were of women who were physically assaulted by their husbands, brothers, or sons, while 57 percent were of children who suffered physical abuse, sexual harassment, or neglect.