In November 1947 the UN voted to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, triggering open war. The divided, poorly led, and ill-equipped Palestinians were no match for the Zionists. On 14 May 1948 the last British troops departed, and the State of Israel was declared on the same day. There were already 300,000 Palestinian refugees.

On 15 May units of the regular armies of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan intervened but, after some initial successes, they failed to block further Israeli advances, let alone recover any lost territory. Only the Arab Legion – whose British officers were under orders from London not to enter any part of Palestine reserved for the Jewish state by the UN – proved a match for the Israelis, expelling them from the Old City of Jerusalem and, with the Iraqis, holding the West Bank.

Fighting continued until January 1949, and later that year Israel signed a series of armistice agreements with the Arab combatant states, except Iraq.

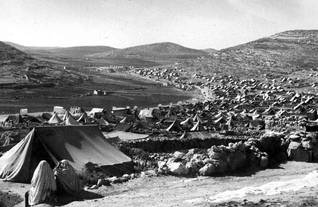

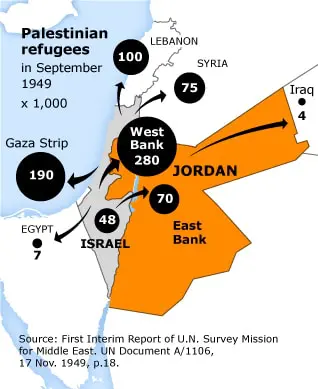

The Palestine war dramatically altered Transjordan’s demography. By May 1949 the West and East Banks had a combined population of 1.43 million, of whom only 476,000 were Transjordanians. Of the Palestinian majority, 519,000 were refugees, most of them living in terrible conditions in tent camps, dependent on handouts from the UN.

Of the refugees, about 100,000 were in the East Bank, mainly in Amman (whose population grew from 50,000 in early 1948 to 120,000 by October 1950), in the north-western town of Irbid, and in the Jordan Valley. The rest were in the West Bank, living amongst the native population of 433,000. Of all the Arab states, only Jordan granted Palestinians citizenship. The Israelis, quietly content that their state had been emptied of nearly 80 percent of its Arabs, did nothing to help.

From his earliest days in Transjordan, Abdullah had maintained discreet links with the Zionists. Later, he would insist that he understood early the Zionists’ power and their potential to cause the Arabs harm and that his aim had been to reach an accommodation with them, as a means of limiting the damage.

He also calculated that his impoverished domain might benefit from Zionist investment and expertise. His dealings with the Zionists were certainly punctuated by demands for cash to replenish his meagre personal coffers. Although Transjordan had been excluded from the Palestine mandate’s pro-Zionist clauses, Abdullah favoured Jewish settlement in his emirate. He and several leading Transjordanian families negotiated land sales to the Zionists. Abdullah was already viewed by many Arabs as a British puppet.

Although the deals were not finalized, his standing fell even further when the Arab press revealed their existence. The key motivation behind Abdullah’s protracted dialogue with the Zionists, however, was the hope that they might aid his territorial ambitions. In the earlier years of the dialogue, he offered them autonomy within a unified Transjordanian-Palestinian kingdom, headed by himself, a proposal that they declined. When war became inevitable, Abdullah quietly assured the British and the Zionists that his forces would not enter the areas allocated to the Jewish state by the UN, explaining that his objective was to annex those parts designated for the Arab state.