Iran’s nuclear program dates back to the second half of the 1970s when Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi decided – with very good reason, as it turned out – that oil in the ground was better than dollars in the bank. He planned to establish a number of large power-generating nuclear plants. Thus the program differed from the Israeli one in that its character was mainly civilian.

However, the possibility that it would one day be made to serve military purposes too could never be ruled out. Given the Shah’s declared ambition of building up Iran into a major regional power capable of ‘protecting’ the Persian Gulf, it was the subject of much speculation during the period in question.

After the Islamic Revolution (1979) the nuclear program was stopped. However it was reactivated by the early 1990s, probably to ensure that Iran would never be as defenceless again as the country had been during its war with Iraq (1980-1988). At that time, the regime of Saddam Hussein had used non-conventional weapons (chemical, biological) on a large scale against the Iranian armed forces and had threatened to use these against major densely populated areas in Iran as well.

Over the years the program has turned into an issue of national pride. Nevertheless, taking into consideration the time that has passed (and the fact that the American nuclear Manhattan Project during World War II only required three years from inception to the day when the first bomb was tested) progress has been surprisingly slow. Whether this is due to technical problems or other factors is not known.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has been closely monitoring Iran, against which Western countries have ordered sanctions. The tension escalated in February 2006, when the IAEA as a whole reported Iran to the UN Security Council. In October 2009, Iran agreed to send enriched uranium to Russia.

In June 2011, former Iranian President Ahmadinejad announced that his country would continue to enrich uranium. Debate over Iran’s nuclear program remains the focal point in relations between Iran and the US and its European allies.

The IAEA

Iran has stated that its uranium enrichment program is exclusively for peaceful purposes. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has confirmed the non-diversion (for weapons purposes) of declared nuclear material in Iran but has also said it ‘needs to have confidence in the absence of possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear program’.

The IAEA has pointed out that Iran is not implementing the requirements of UN Security Council Resolutions and needs to cooperate to clarify outstanding issues and meet requirements to provide early design information on its nuclear facilities.

In a 2007 National Intelligence Estimate, the United States Intelligence Community assessed that Iran had ended ‘nuclear weapon design and weaponization work’ in 2003. In 2009, US intelligence assessed that Iranian intentions were unknown but that, if Iran pursued a nuclear weapon, it would be ‘unlikely to achieve this capability before 2013’ and acknowledged ‘the possibility that this capability may not be attained until after 2015’. Iran has called for nuclear-weapons states to disarm and for the Middle East to be a nuclear-weapon-free zone.

After the IAEA voted in a rare non-consensus decision to find Iran in non-compliance with its NPT Safeguards Agreement and to report that non-compliance to the UN Security Council, the Council demanded that Iran suspend its nuclear enrichment activities and imposed sanctions against Iran when Iran refused to do so.

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad argued that the sanctions are illegal. The IAEA has been able to verify the non-diversion of declared nuclear material in Iran but not the absence of undeclared activities. The Non-Aligned Movement has called on both sides to work through the IAEA for a solution.

In November 2009, the IAEA Board of Governors adopted a resolution against Iran that urged Iran to apply the modified Code 3.1 to its Safeguard Agreement and to implement and ratify the Additional Protocol, and it expressed ‘serious concern’ that Iran had not cooperated on issues that needed ‘to be clarified to exclude the possibility of military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear program’.

Iran said the ‘hasty and undue’ resolution would ‘jeopardize the conducive environment vitally needed’ for successful negotiations and lead to cooperation not exceeding its ‘legal obligations to the body’. Iran and the West have, nevertheless, continued at odds over Iran’s nuclear program. The dispute has intensified since November 2011, with new findings by international inspectors, tougher sanctions by the United States and Europe against Iran’s oil exports, threats by Iran to shut the Strait of Hormuz, and threats from Israel signaling increasing readiness to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities.

On 1 August 2012, while on a visit to Israel, US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta took a tough tone against Iran by implicitly threatening an American military attack if Iran decides to develop a nuclear weapon.

In the summer of 2012, the United States and its European allies imposed new sanctions that were meant to cut Iran off from the global oil market, hoping that the sanctions would force Iran to change its course. Even before these steps, Iran’s oil exports were down 20 to 30 percent, and its currency had fallen more than 40 percent against the dollar since 2011.

But the escalating sanctions, which the Bush administration began and the Obama administration has intensified, have so far failed in their primary goal of forcing Iran to stop uranium enrichment. Iran responded to the new sanctions with a series of defiant steps, announcing legislation intended to disrupt traffic in the Strait of Hormuz, a vital Persian Gulf shipping lane, and testing missiles in an exercise clearly intended as a warning to Israel and the United States.

Iran has, over the last few years, been the target of a series of cyber attacks, some of which were linked to its nuclear program. It has been reported that President Obama, during his first few months in office, secretly ordered increasingly sophisticated attacks on Iran’s computer systems at its nuclear enrichment facilities, significantly expanding America’s use of cyber-weapons.

The best known of these was Stuxnet, a computer worm, or malicious computer program, that turned up in industrial programs around the world in 2009. Stuxnet, which had been developed by the United States and Israel, appears to have wiped out nearly 1,000 of the 5,000 centrifuges Iran had spinning at the time to enrich uranium.

In May 2012, a data-mining virus called Flame penetrated the computers of high-ranking Iranian officials, sweeping up information from their machines. In a message posted on its website, Iran’s Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Center warned that the virus was potentially more harmful than Stuxnet. In contrast to Stuxnet, Flame appeared to be designed not to do damage but to secretly collect information from a wide variety of sources.

Ballistic missiles program

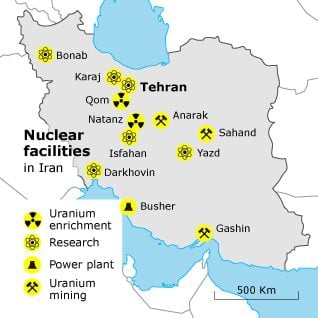

To protect the program, its components are widely dispersed over Iran’s territory. Probably not all of them have been identified by foreign intelligence services. Its most important elements are the plant at Natanz, where uranium is being enriched, and the reactor at Bushehr, which when completed will provide Iran with plutonium.

Unlike Israel, Iran has signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Like the Israelis, the Iranians have never admitted that their goal is to build a bomb – for very good reason, given the very real danger that, should they do so, they would come under attack by Israel, the United States, or both. In fact, to date, scant positive proof exists that they are building a bomb.

However, Iran does have a large and very active program for developing ballistic missiles. Some of them can reach any target within a radius of about 2,000 kilometres. Since such missiles hardly make military sense without nuclear warheads, it must be assumed that Tehran is in fact doing whatever it can to develop, if not an actual bomb, then at least the option of building one quickly should the need to do so arise.

Additionally, reports in 2002 and 2003 of research on fuel enrichment and conversion raised international concerns that Iran might be working on a nuclear-weapons program. However,Iran is not known currently to possess weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and has signed treaties repudiating the possession of WMDs, including the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention, in addition to the NPT.

On religious grounds, a decree (fatwa) against the development, production, stockpiling, and use of nuclear weapons has been issued by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, along with other clerics.