Introduction

Two developments in Iranian society are especially pronounced: the rapid urbanization and the population growth in the past decades. Both have had a great impact on social relations. Educational levels have risen, yet health care, housing and employment are lagging behind.

Civil Society

Civil society in Iran is one of the region’s most active, but it is currently under more pressure than civil society in many other countries in the region. There are estimated to be from 5,000 to 8,000 NGOs active in Iran, including Islamic charities, as well as secular organizations, local groups, and internationally known organizations. Iranian NGOs cover a wide spectrum of issues, from environmental protection and human rights to poverty alleviation and domestic violence.

Civil-society activism developed as a result of the brief openness during the tenure of reformist President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). Khatami tried to promote concepts such as freedom of thought, pluralism, civil society, and the rule of law and provided subsidies to help develop the NGO sector, but he failed to institute safeguards to prevent its dismantlement.

Registration of any NGO in Iran requires a permit from the Interior Ministry. Few NGOs have been granted official recognition by the government, and they face arbitrary inspection and closure. Another problem is funding: donations, especially foreign, to Iran’s NGOs are subject to severe restrictions. Iranian NGOs have recently tended to avoid associating with foreign-based NGOs, for fear they may arouse suspicion. While civil society is still very active, many participants and activists have, since the government crackdown on activism, pulled back from some politically more sensitive topics.

Women

Although increased social and physical mobility have caused some social change, Iran remains a conservative society, with the family as its cornerstone. Women fall under the authority of the husband or the husband’s family, but women are gaining more financial independence through increasing employment, especially in the cities.

One of the most visible changes since the Revolution has been the curtailment of women’s rights and freedom. Female judges were fired, the veil was made mandatory, and laws based on Sharia (Islamic law) institutionalized gender inequality. Family law was changed so that women had less to say in child-custody cases and in their own careers. Filing for divorce was made extremely difficult for women. A woman’s testimony in court counts for only half of that of a man. The same is true for the payment of diyeh (blood money). Violence and discrimination against women are common in Iranian society, as are ‘honour crimes’.

At the same time, the number of women participating in higher education and the labour force has risen tremendously. In 2007 over 60 percent of university students were female. As a result of greater educational equality, women in Iran are becoming as educated and skilled as men. Nevertheless, they make up a significant proportion of the unemployed. While Iranian women comprise around two-thirds of university entrants, they make up only one-fifth of the labour force.

According to the Iranian census of 2006, 3.5 million Iranian women are salaried workers, compared to 23.5 million men. The female share of the labour force is less than 20 percent, considerably lower than the world average of 45 percent. More than a third of Iran’s female labour force is in professional jobs, mostly in education, health care, and social services.

Women’s movement

In recent years women’s-rights activists have become Iran’s most active and visible proponents of change. Hundreds of small NGOs work to improve the rights and status of Iranian women. The Change for Equality and its One-Million-Signatures Campaign, for instance, was organized by Iranian women’s rights activists aiming to collect a million signatures demanding changes to discriminatory laws against women. Leaders of the movement have been attacked and jailed by the government, and many remain incarcerated.

Family

The family is the most important element of Iranian culture and society and is defined in the Constitution as the fundamental unit of society. Kinship and family constitute a tightly linked network, in which the highest priority is assigned to the welfare of the members rather than to individual goals. People rely on family connections for influence, power, and security. In traditional Iranian families the individual’s life is dominated by the family and family relationships.

The typical Iranian family household is extended to include grandparents. The extended family has traditionally been the basic social unit. In rural areas the maintenance of this pattern is crucial for survival in hard times and so is generally preserved. In urban areas the significance of the extended family has diminished because of the geographical dispersion of the extended family and differences in status and material wealth.

Marriage in Iran is traditionally viewed not only as the only socially acceptable pathway to sexual relations but also as a permanent commitment, bonding not only the married couples but also their families. Procreation is a primary goal of marriage, and infertility is seen by some as an adequate justification for divorce.

Arranged marriage is common in Iran, especially in rural areas. A delegation of parents and elders from the man’s side are usually responsible for the khastegari, the formal marriage proposal. During their first meeting, the two families discuss the marital contract, in which matters such as the size of the dowry are settled.

Among upper- and middle-class urban families, the khastegari still plays an important role, but the initiative lies with the couple intending to marry. Marriages arranged by parents on behalf of their young children are rare.

Polygamy is allowed in Iran. According to Shiite marriage law, a man may have as many as four wives simultaneously. Polygamy is, however, frowned upon by many in Iran and is rarely practised.

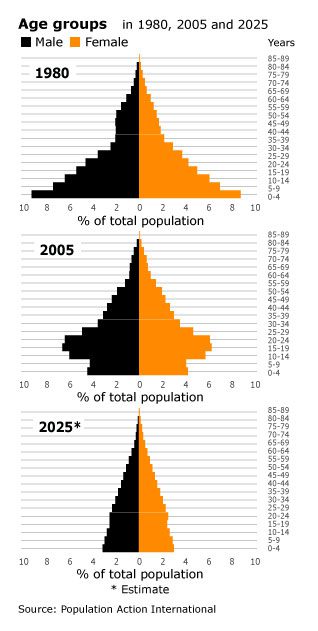

After the Revolution, the new government adopted a pro-natalist approach. Family planning was seen as a Western influence, and contraception was no longer promoted. The legal minimum age for marriage was lowered to nine for girls and twelve for boys. After the war, the Iranian leadership revised its perception of family planning. With a ruined economy, job shortages, and overcrowded cities, population growth was seen as detrimental to development.

Thanks to family planning education, the widespread use of contraceptives, and the sharp decline in fertility, family size has declined, and socio-political changes have affected young people’s view of marriage and the structure and functioning of the family.

Although the Islamic regime encourages early marriage (based partly on the disapproval of premarital sex), the average age at first marriage during the period 1976-1996 increased from 19.7 to 22.4 for women, and from 24.1 to 25.6 for men, and divorce rates increased gradually. Divorce is strongly discouraged in Islam and disapproved of in Iranian culture. For women, especially, divorce has far-reaching consequences, because of their usual economic dependence on men and because of social disapproval of divorced women.

‘Temporary marriage‘ (siqeh) is another form of legal cohabitation between men and women. While no duration is specified in permanent marriage, a temporary marriage can last for a specified time. A man (either married or single) and a single woman agree on the period of the relationship and the amount of compensation to be paid to the woman.

In siqeh, the wife is not entitled to any financial support or inheritance from the husband. Proponents of siqeh argue that it curbs free sex, controls prostitution, and supports divorced or widowed women, but siqeh is very unpopular with many Iranians, particularly those of the middle and upper classes. Opponents argue that siqeh is, in fact, a form of legalized prostitution.

Health

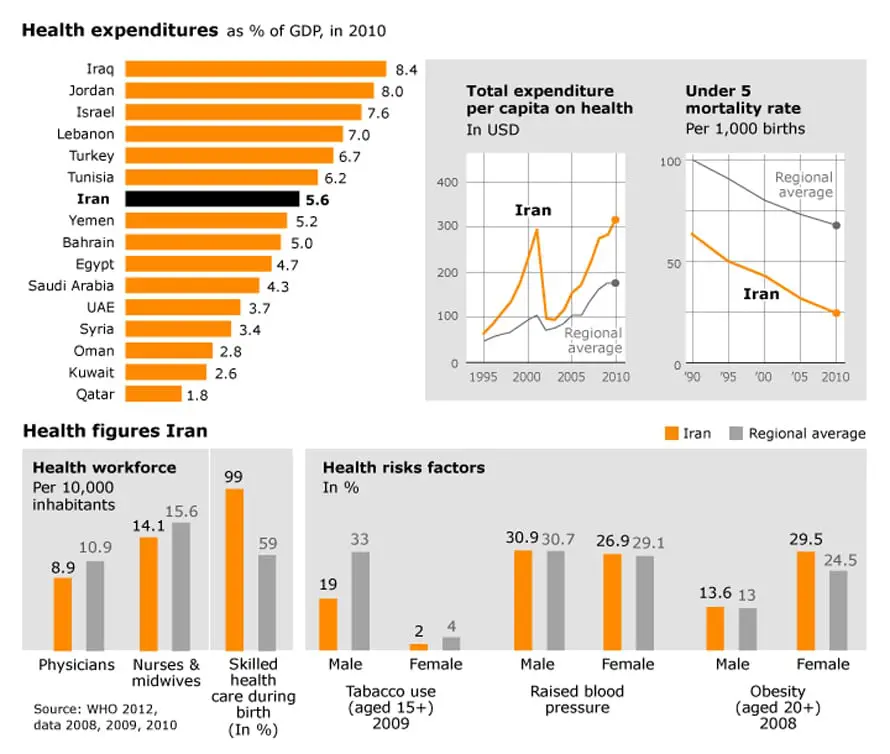

The Ministry of Health and Medical Education finances and delivers primary health care. The establishment of a national health care system has resulted in major improvements in health. The overall life expectancy in Iran rose from less than 62 years in 1988 to almost 70 years in 2000 and 74.3 years in 2013.

The incidence of several communicable diseases has been reduced, and maternal and child health have improved. Mortality rates for infants (less than 1 year old) and children (up to five years old), which were as high as 93 and 153 per 1,000 live births in 1974, had fallen to about 21 and 25 respectively by 2009.

Challenges remain: more than 8-10 percent of the population is not covered by insurance and has to pay directly for health care. There are still some sectors of the population that have no access to health care. The availability of services is low, especially in rural areas and the less developed provinces, such as Sistan and Baluchistan.

Halting and reversing the HIV/AIDS epidemic by the government-imposed deadline of 2015 represents one of the major challenges facing Iran. According to the World Health Organization ‘the estimated number of HIV-positives is greater than 30,000, with 700 AIDS cases’.

Intra-venous drug use and needle sharing are major problems, particularly among the prison population. If needle sharing (accounting for 62 percent of transmissions) is not dealt with properly, the consequences for the spread of HIV and hepatitis may be catastrophic. Because a large part of Iran’s population is now coming of reproductive age, increased services will be required for the promotion of sexual health and responsible behaviour (at present, 8-9 percent of HIV/AIDS cases are infected through sexual contact.)

Drug addiction is a major problem in Iran. In 2009 the number of drug abusers (including opium and heroin) was estimated to exceed 1.2 million and to be on the increase. According to official estimates, about 130,000 people in Iran become addicted to drugs each year. In spite of its harsh anti-drugs policies, the government is, according to some Iranians, responsible for the high addiction rate. The lack of employment and strict social control drives Iranian youths towards the use of drugs.

Education

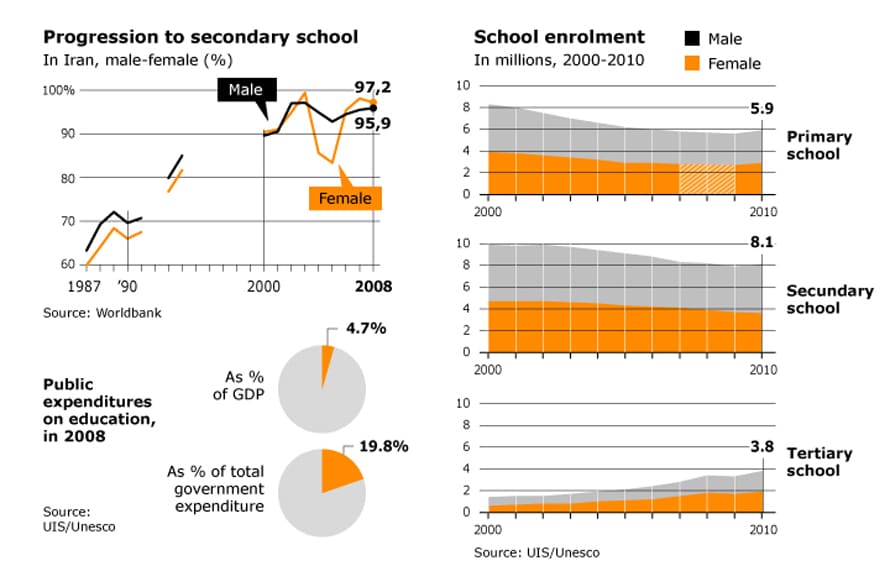

Seventy-seven percent of the total population fifteen and older can read and write. The level of girls’ education has risen, and the gap between male and female education has shrunk. A 2012 estimate shows that 89.36 percent of the male population and 79.23 percent of the female population is literate.

Primary education (ages six to ten) is compulsory; primary enrolment was nearly 98 percent in 2004. Secondary-school attendance is not compulsory; in 2004 enrolment was about 90 percent for middle school and 70 percent for high school. Public education is free; only private schools and universities charge tuition.

The majority of Iran’s pre-collegiate public schools are single-sex. universities are coeducational. Because more than half of the country’s population is under the age of 25, the education system is under great pressure. There are more than 113,000 schools throughout Iran, teaching more than 18 million children. It is estimated that there are almost 1 million teachers in the education system.

In 2014, Iran had more than 200 public and more than 30 private institutions of higher education, serving about 4.5 million students. Admissions to post-secondary courses are highly competitive, and university places are won through the National Entrance Examination (Konkur, from the French term concours). The largest and most prestigious public university is the University of Tehran. In 2007 more than 60 percent of university students were female. The academic year runs for 10 months, from September to June.

While the closing of the gender gap in education has been praised as one of Iran’s important achievements, there are rising concerns inside Iran about women outnumbering men in universities. Hard-line members of Parliament have occasionally branded women’s increased numbers a risk and have called for a gender quota. They have argued that, because men are the traditional bread winners, they have to be guaranteed places in higher education and the workforce. Another argument is the rising age of marriage, and divorce numbers. Iran has admitted men and women by quota in some fields in recent years, but in 2008 plans were launched mandating that both men and women should constitute at least 30 percent of registrants in all university courses.

In 2010 Iran had 3,790,859 college students, of whom about 50.5 percent were men. In previous years it had been reported, based on official figures, that women made up 60-65 percent of university entrants.

Youth

The National Youth Organization defines a youth as a person aged 14-29 years. Because nearly three quarters of Iran’s population is under the age of 30, its youth are an important force. The high birth rate in the years following the Revolution (1979-1991) affected the economy and reduced the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) and still has a large impact on Iran’s society and economy.

Entry of this group into the job market has created high unemployment. In 2014, unemployment was particularly high among those aged 15-24, estimated at 26.1 percent for men and 41.4 percent for women. Marriage and family creation in this large population group will also increase the demand for housing and will generate a second wave of increased fertility.

Economic activities for youth involve mainly information technology, communications, and services: in the latter area young people are attracted primarily to governmental and related job systems.

Iranian youth are also an important political factor. In January 2007, the voting age was raised to eighteen years from fifteen. Many of Iran’s youthful population, born after the 1979 Revolution, long for a relaxation of the government’s strict social and political control.

Former reformist President Mohammad Khatami credited his landslide victories mostly to Iran’s youth and women. Until the violent crackdown on student protests in 1999, student activism was the most important force in pushing the government toward change. Although less visible than before, universities remain important sources of activism and protest.

Many of Iran’s youth expressed their power and potential in support of the Green Movement and through their opposition to the controversial presidential elections of 2009.

Urbanization

Iran has one of the highest urban growth rates in the world, largely the result of internal migration from rural areas. Mass urbanization is caused mostly by the lack of investment in rural areas. The Iran-Iraq War also contributed to rapid urbanization, when millions of internally displaced people (IDPs) fled to large towns.

According to World Bank estimates, about 73 percent of the population was living in urban areas. It has been estimated that by 2020 about 75 percent of the population will live in urban areas. Slums, high unemployment rates, poor public services, and a weak economy are partly the result of the high urban growth-rate.

To limit the high urbanization rate, the government in 2003 initiated a ‘reverse-migration initiative’ by investing heavily in industries, agriculture, and public services in areas such as Iran’s largest province, Khorasan.

Crime

Violent crimes and crimes against property are increasing modestly. Violent crimes in 1994 were at 120 per 100,000 but amounted to 150 per 100,000 in 2004.

With 225,624 prisoners (2014 est.), Iran ranks tenth in the world in prison population. According to Mehr News Agency, the average age of prisoners in Iran is 28. An estimated 60 percent of inmates have been imprisoned for drugs-related crimes.

Organized criminal networks in Iran traffic narcotics, people, and small arms. According to the 2007 UN World Drug Report in 2006, out of all opiates originating in Afghanistan, 53 percent were shipped via Iran. Iran also had the highest percentage of seizures of transported drugs.

According to a US Department of State 2007 Trafficking in Persons Report, Iran is also a source, transit, and destination country for women trafficked for the purposes of sexual exploitation and involuntary servitude; Iranian women are trafficked internally for the purpose of forced prostitution and for forced marriages to settle debts; Iranian children are trafficked internally and Afghan children are trafficked into Iran for the purpose of forced marriages, commercial sexual exploitation, and involuntary servitude as beggars or laborers’.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Iran’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: