Introduction

Iranian newspaper printing began in 1836, but the first notable publication, Vaghaye-e-Etefaghiyeh, first appeared in 1847. It was largely based on translations from the European and Turkish press and was subsequently the first newspaper to be subject to the censorship of the ruling authorities. However, the majority of early Iranian newspapers were overwhelmingly supportive of the government.

By the time of the Persian Constitutional Revolution in 1907, the print media in Iran had rapidly developed, with an estimated 84 publications available in the country. Newspapers had also begun to reflect diverse Iranian political opinions and affiliations. Press freedom, however, was compromised by the influence and interference of foreign powers, notably Britain and Russia, in Iranian affairs, as well as by the onset of World War I.

The Pahlavi government consolidated its power throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and simultaneously increased its control over the domestic press. Between 1925 and 1941, the number of Iranian newspapers declined from 150 to around 50, while the first efforts to establish a broadcast mass media system were put in place. In 1940, Radio Tehran was launched, broadcasting for eight hours per day. The Pahlavi state briefly attempted to ban the reception of foreign radio broadcasts, which ultimately proved unfeasible.

The early 1950s witnessed a relatively free media environment in Iran. The rise of Mohammad Mossadeq, who was elected prime minister on 28 April 1951, was aided considerably by the print media and radio in order to galvanize support for his oil nationalization movement. However, following his overthrow in 1953, the media environment reverted to strict state control. Political parties were banned, criticism of the monarchy was criminalized and the state enforced its control over the press and radio through the Ministry of Information and the SAVAK secret police.

Television was first introduced in 1958 as a privately owned enterprise named Television Iran, although early broadcasts were foreign imports dubbed into Farsi. The medium quickly became popular among middle-class Iranian households and Television Iran was eventually nationalized in 1969. This would form part of a government broadcast monopoly in addition to the National Television Network channel, which was established in 1966.

After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the Iranian media environment became even more state-dominated and repressive. In the first ten years following the revolution, there was a large-scale arrest and execution campaign against journalists who had supported the Pahlavi regime. Judges were able to prescribe sentences ranging from imprisonment and flogging to death sentences. Criticisms of Islam, the revolution or government officials, in addition to the publication of ‘false news’, were criminalized. During 1979 alone, around 30 newspapers were banned for not advocating Islamic values or the ‘goals of the revolution’. The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) corporation was also established, replacing the National Iranian Television and Radio network, to censor all broadcast content deemed damaging to Islam or the ruling establishment.

As the Pahlavi state had attempted previously, the Islamic Republic also tried to minimize the influence of foreign media products. State television throughout the 1970s and 1980s primarily aired Islamic programming designed to promote the religious legitimacy of the Iranian leadership, to the extent that it was labelled ‘Mullahvision’ by disgruntled domestic viewers because of its repetitive content.

When satellite technology was introduced in 1993, foreign programming initially proved hugely popular among Iranian audiences who appreciated the diversity and choice. In response, and to guard against the potential ‘moral depravity’ of foreign broadcasts, the Iranian government outlawed satellite dishes in 1995 (a law that officially remains in place), but Iranian audiences quickly devised strategies to circumvent the ban.

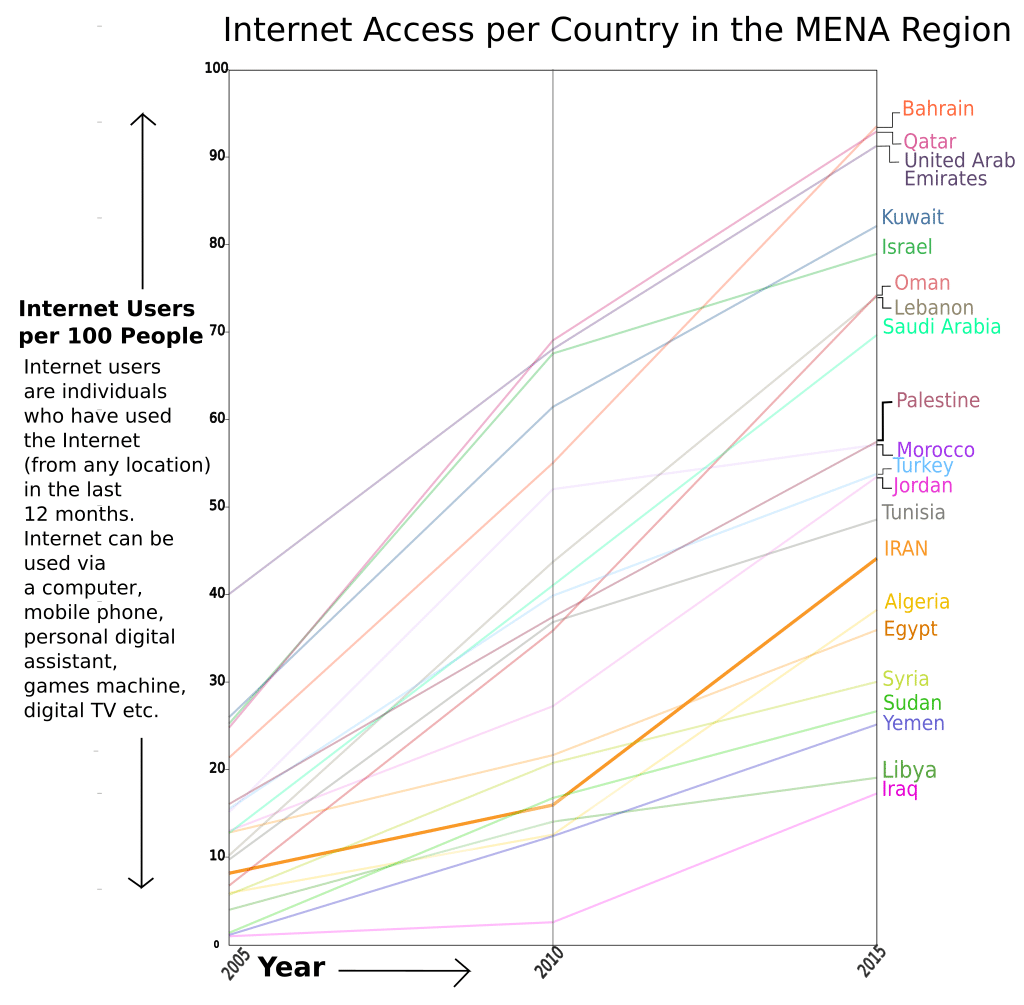

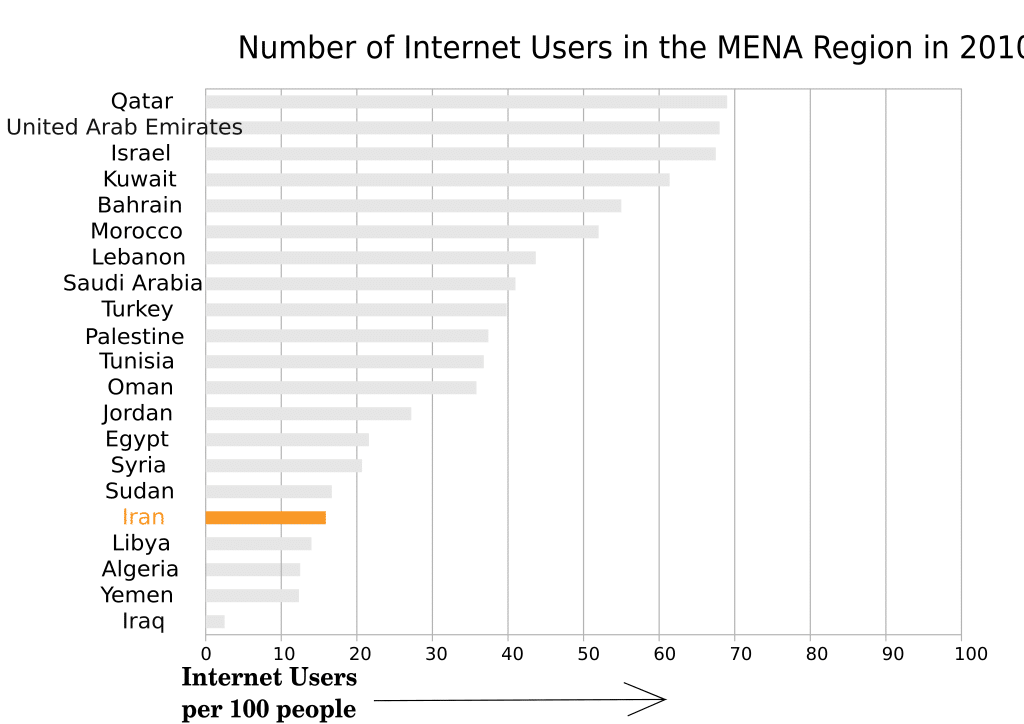

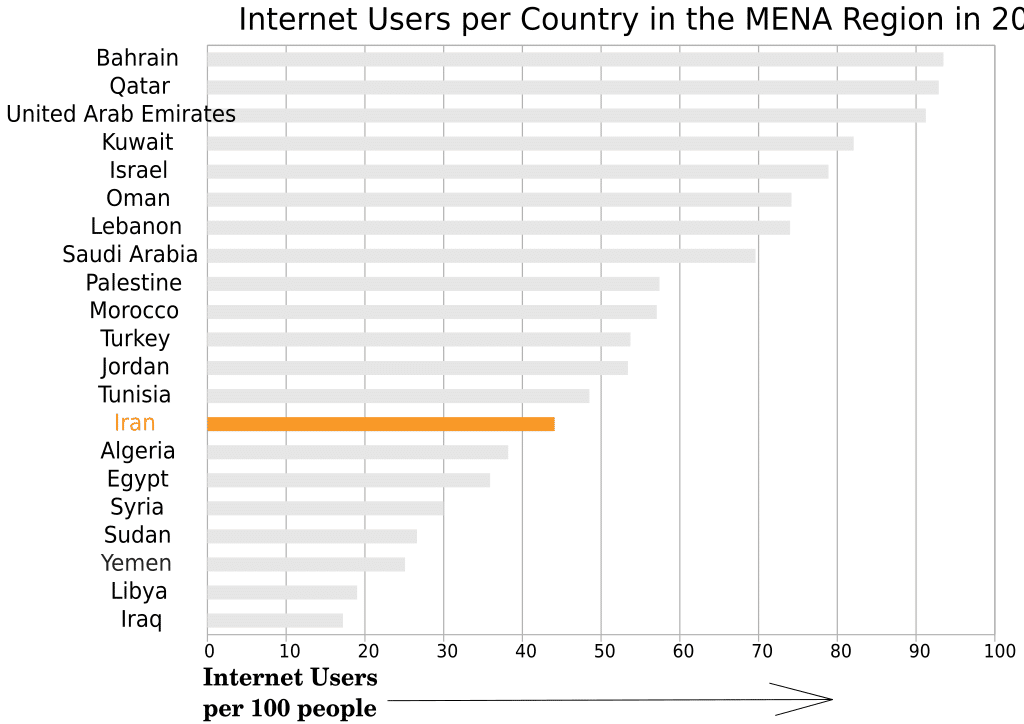

The internet was introduced in 1993, but has since been tightly regulated by the state. Nevertheless, such technological advancements by the end of the 20th century saw Iranians becoming increasingly exposed to alternative news sources. Domestic press regulations were also relaxed in 2000, with amendments to the country’s 1986 Press Law allowing for ‘constructive criticism’ of the state and officials, as long as this served the ‘best interest of the community’.

When President Mohammad Khatami came to power in 1997, there were signs that a more pluralistic press environment would be tolerated. Licenses were immediately restored to several banned publications such as Jahan-e Eslam, a radical newspaper published by the Supreme Leader’s brother, which had previously been outlawed for two and a half years. A journalist’s union was also established, and by the end of 1997, a more outspoken and critical press was emerging. However, this phenomenon was ultimately short-lived, as by the summer of 1998, Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei once again sought greater media control and labelled the country’s newly outspoken outlets as “a dangerous, creeping cultural movement”. He ordered Khatami to re-close several publications, threatening to intervene personally otherwise.

The early 21st century media environment fluctuated between periods of relative openness and restriction. However, any initial optimism was ultimately quashed following the events of the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, which prompted a government crackdown on dissenting media voices. Foreign journalists were temporarily expelled and a mass arrest campaign was undertaken to target domestic reporters. The government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad also sought to dramatically cut subsidies underpinning the country’s more liberal newspapers.

Since the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani, most observers attest that the contemporary media environment is less restrictive, however censorship and online surveillance remains pervasive, and media outlets are routinely closed if they are deemed to have crossed any of the numerous journalistic red lines.

Freedom of Expression

Iran’s media environment is repressive and closely controlled, and ranks 169th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2016 World Press Freedom Index. The Iranian constitution, amended in 1989, states that ‘publications and the press have freedom of expression except when it is detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public’. The exceptions to this freedom are outlined by Iran’s press law and penal code. The press law, enacted in 1986 and amended in 2000, stipulates that publications must observe Islamic teachings and act in the best interest of the community, but otherwise permits freedom of expression. The penal code, however, criminalizes ‘propaganda’ against the Iranian state, permits death sentences for those who insult Islam and stipulates flogging and jail terms for those who intentionally foster ‘public unease or anxiety’ or spread false rumours.

Censorship is widespread, and in 2015, the state was ranked as the 7th most censored country in the world by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Print media is subject to state interference, broadcasted material on terrestrial television continues to be monitored and censored by IRIB, while millions of websites, including news portals and social networks, are officially blocked. Proxy networks are becoming more popular among the Iranian population and, in 2014, Rouhani acknowledged that online censorship was ineffective, likening it to a “wooden sword”. However, despite stating that censorship and media restrictions would be relaxed during his tenure, he has yet to enact significant reforms in this regard.

Iran also has a notorious reputation for imprisoning its journalists. In 2009, Iran became the world’s leading jailer of journalists, according to the CPJ, and has ranked highly in its annual top ten list ever since. In 2016, the country was estimated to be holding eight journalists in prison, a marked decrease on recent years. Those who remain incarcerated include Mohammad Kaboudvand, editor of the weekly Kurdish publication Payam-e-Mardom, which has since been banned. Kaboudvand was arrested in 2007 and charged with acting against national security and spreading propaganda against the state. He was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment and has since undergone several hunger strikes to protest for visitation rights and in an attempt to fight new charges being brought against him.

Isa Saharkhiz, a journalist and former head of the press department at the Ministry of Culture, was first arrested in 2009 for ‘spreading propaganda’ and released in 2013. He was imprisoned once again for ‘insulting Iranian officials’ in 2014 and released after 21 months. In April 2017, he was imprisoned for a third time and ordered to serve another year in jail for ‘insulting the former president’.

In 2015, freelance journalist and blogger Saeed Pourheydar was sentenced to five years’ in prison for ‘insulting the Supreme Leader’ and publishing false information online. Pourheydar had previously written for several reformist media outlets based both within Iran and abroad, having lived in the United States from 2010 to 2014. He had also been arrested twice in the aftermath of the 2009 Iranian presidential election. Also in early 2015, cartoonist Atena Farghadani was sentenced to over 12 years’ in prison for publishing artwork on Facebook that was deemed insulting to members of parliament and the Supreme Leader. Following an international campaign against her sentence, Farghadani was released from prison in May 2016. Foreign journalists operating in Iran have also faced state repression and arrest. The most notable recent example is American journalist Jason Rezaian, who worked as the Washington Post’s Tehran correspondent but was imprisoned from 2014 to early 2016 on charges of espionage.

Media outlets that are relatively independent or advocate an overly reformist slant are often forcibly closed down by the Iranian judiciary, which falls under the Supreme Leader. In 2015, the newspaper Mardom-e-Emrooz was shut down after its front page expressed solidarity with victims of the Charlie Hebdo shooting in France, while reformist newspaper Ghanoon’s license was suspended in 2016, following a complaint from the Islamic Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) about its ‘intent to disrupt public opinion’.

Television

IRIB, the head of which is appointed by the Supreme Leader, has a monopoly over terrestrial broadcasting in Iran. It operates 12 national, 33 provincial, two internet and ten international broadcast channels. Television is the most popular medium in the country, with an estimated 80 per cent of citizens relying on television as their primary news source.

Despite being officially banned, satellite dishes are popular among Iranian households to access foreign broadcasts. In 2016, officials destroyed 100,000 dishes as part of the government’s latest crackdown, however Rouhani himself has acknowledged that the ban is increasingly ineffective, especially in light of online streaming and advancements in satellite technology.

IRIB’s most significant channels are as follows:

IRIB TV 1 – Founded in 1958 as a private enterprise and nationalized just over a decade later. IRIB TV 1 is the state’s flagship channel and airs a variety of entertainment programming and talk shows, in addition to popular news broadcasts.

IRIB TV 3 – Established in 1993 as IRIB’s third channel, specifically targeting young viewers with its focus on entertainment and sports broadcasting. The channel also hosts ‘Navad’, IRIB’s most popular production, which mainly serves as a football-based talk show but also incorporates aspects of politics and societal issues.

Al-Alam – Arabic-language news channel launched in 2003, with the intention of targeting Arab viewers with Iranian political and religious rhetoric. The channel has provoked hostile reactions from Saudi Arabia and affiliated Arab states. In 2014, the station was taken off air by Arab satellite broadcasters in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, while in 2015, an Emirati minister accused the channel of spreading ‘false news’.

Islamic Republic of Iran News Network (IRINN) – 24-hour rolling news channel established in 1999. The channel also features talk shows and broadcasts worldwide.

IRIB Quran – Religious channel launched in 2005 that broadcasts worldwide.

Al-alam TV Channel. Photo Flickr

Press TV – Established in 2007 as a 24-hour English-language news, talk show and documentary station broadcasting worldwide. It airs content designed to promote Iran’s political ideology and hosts a variety of international popular figures to appeal to regional audiences. In 2012, the channel’s license to broadcast in the UK was revoked following an investigation into the 2010 airing of a confession from imprisoned journalist Maziar Bahari, which had been extracted under duress.

Radio

Like television, IRIB holds a monopoly over radio broadcasts in Iran. IRIB’s most notable national stations include Sarasary, which serves as the main state radio station, also known as Radio Iran, airing news and talk shows. Javan is a youth-orientated station that broadcasts Iranian music. Payam airs a mixture of news and music programming with a focus on urban citizens, mainly in Tehran. Maaref is a cultural station based in the city of Qom, with a particular emphasis on religious content. Finally, Quran Radio airs religious verses and recitations.

Press

Iran has a competitive press environment, with over 50 national daily publications. Reliable circulation figures are difficult to obtain, but those with the largest reach tend to be editorially conservative or state-operated. A selection of major daily newspapers includes:

Kayhan – Established in 1943, with an extremely conservative editorial tone. Since 1979, the publication has served as a mouthpiece for the Supreme Leader, who also appoints the newspaper’s managing editor. Kayhan enjoys privileged access to the Iranian judiciary and security officials, and is considered one of the country’s most influential newspapers.

Resalat – First published in 1985 and owned by the conservative Resalat Foundation. The newspaper publishes political, cultural and social news that reflect its traditionalist, religious values.

Iran – Government-operated newspaper published by the official Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) since 1995. The newspaper has twice been closed down, first in 2006, after the publication of a cartoon deemed offensive to the country’s Azeri community, leading to the arrest of the cartoonist, and again in 2013, after allegations of false reporting.

Shargh – Founded in 2003 and considered one of the most popular reformist newspapers in Iran. During the first decade of its publication, the newspaper was closed down on four separate occasions after violating press regulations, and has since adopted a more neutral editorial stance. Iranian authorities regularly arrest the newspaper’s employees, with Reporters Without Borders citing three examples of Shargh-affiliated journalists detained in 2016, including the former political editor.

Aftab Yazd – Launched as a national newspaper in 2000, after previously having been restricted to its local province. Aftab Yazd is often critical of the conservative factions of the Iranian government and adopts stances that reflect prominent moderate clerics.

Mardomsalari – Official publication of the Democracy Party of Iran (Mardomsalari). During the 2009 presidential elections, the newspaper openly supported opposition candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi and was fiercely critical of the government crackdown against the resulting protests. The newspaper has since relaxed its tone following government warnings.

Tehran Times – Established in 1979 as the country’s first English-language daily. It follows a conservative editorial line and invites contributions from international writers in an effort to boost its overseas appeal.

Online Publications

One of the most distinctive aspects of the Iranian media environment is the plethora of news agencies that have emerged since the introduction of the internet. The major news agencies are as follows:

Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) – Iran’s official news agency has been in operation in some form since 1934, and was one of the first news platforms to migrate online in 1997. It often serves as the mouthpiece for official government statements and publishes in eight different languages.

Mehr News Agency – Established in 2003 as a private news agency owned by the Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organization (IIDO). Its managing director is Ali Asgari, who also heads the Tehran Times.

Fars News Agency – Established in 2003 as a semi-official state news agency affiliated to the IRGC. It offers content in Farsi, Arabic, English and Turkish. The agency has a reputation for its conservative, hardline editorial stance but also for occasional outlandish reporting and conspiracy theories. In 2014, it reported that an ‘alien/extraterrestrial intelligence agenda’ was driving the US government’s domestic and international policy.

Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA) – Founded in 1999 as a news portal operated by Iranian students. Originally with a remit for academic and university news, ISNA has since expanded to cover national and international topics. It is considered a more independent and moderate platform than IRNA.

Iranian Labour News Agency (ILNA) – Founded in 2003 as a news agency dedicated to the country’s workforce, operating under the auspices of the Worker’s House, a labour union established by the government. This news agency is considered relatively close to the Iranian reformist movement.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Iran’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media

The mass protests of 2009 were dubbed by many Western observers as a ‘Twitter revolution’, with reports of activists using social media, email, blogs and SMS messages to coordinate demonstrations, and mobilize and locate support. In recent years there has been a growing tendency to downplay the importance of online and mobile communication in the events of 2009, with new research arguing that word of mouth was the most influential mobilization tool, while online activities left a digital trail that could be exploited by the security services.

Nevertheless, since 2009, major social media platforms such as Twitter, YouTube and Facebook have been blocked in Iran. Many Iranian citizens still access the sites and operate profiles via proxy networks, although due to the official ban accurate usage statistics are difficult to obtain. In a seemingly contradictory practice, Supreme Leader Khomeini has a Twitter account, and the president has accounts on both Twitter and Facebook, as do other high-profile Iranian officials including Foreign Minister Javad Zarif.

In 2014, the Iranian authorities also blocked several mobile messaging platforms, including WhatsApp and Viber, after several people were arrested for sending insulting messages about Iranian officials and the Supreme Leader. The relatively new instant messaging service Telegram has since gone on to become the most popular permitted platform in Iran, with an estimated 20 million users in 2015. Instagram is also popular, having so far avoided official sanction.

Content posted to social media platforms and blogs is heavily monitored and the authorities impose severe penalties on those who express too much criticism or dissent online. Iranian artist Hadi Heidari was arrested in November 2015, after posting a cartoon on Facebook in solidarity with victims of the Paris terror attacks. He was released in April 2016. Also in April 2016, journalist Mohammad Fathi was sentenced to 444 lashes for publishing an article on his blog that criticized the municipal government. Hossein Maleki, a blogger who helped other citizens circumvent online censorship regulations, was released in May 2016, having being held since 2009.