Conquest of Morocco

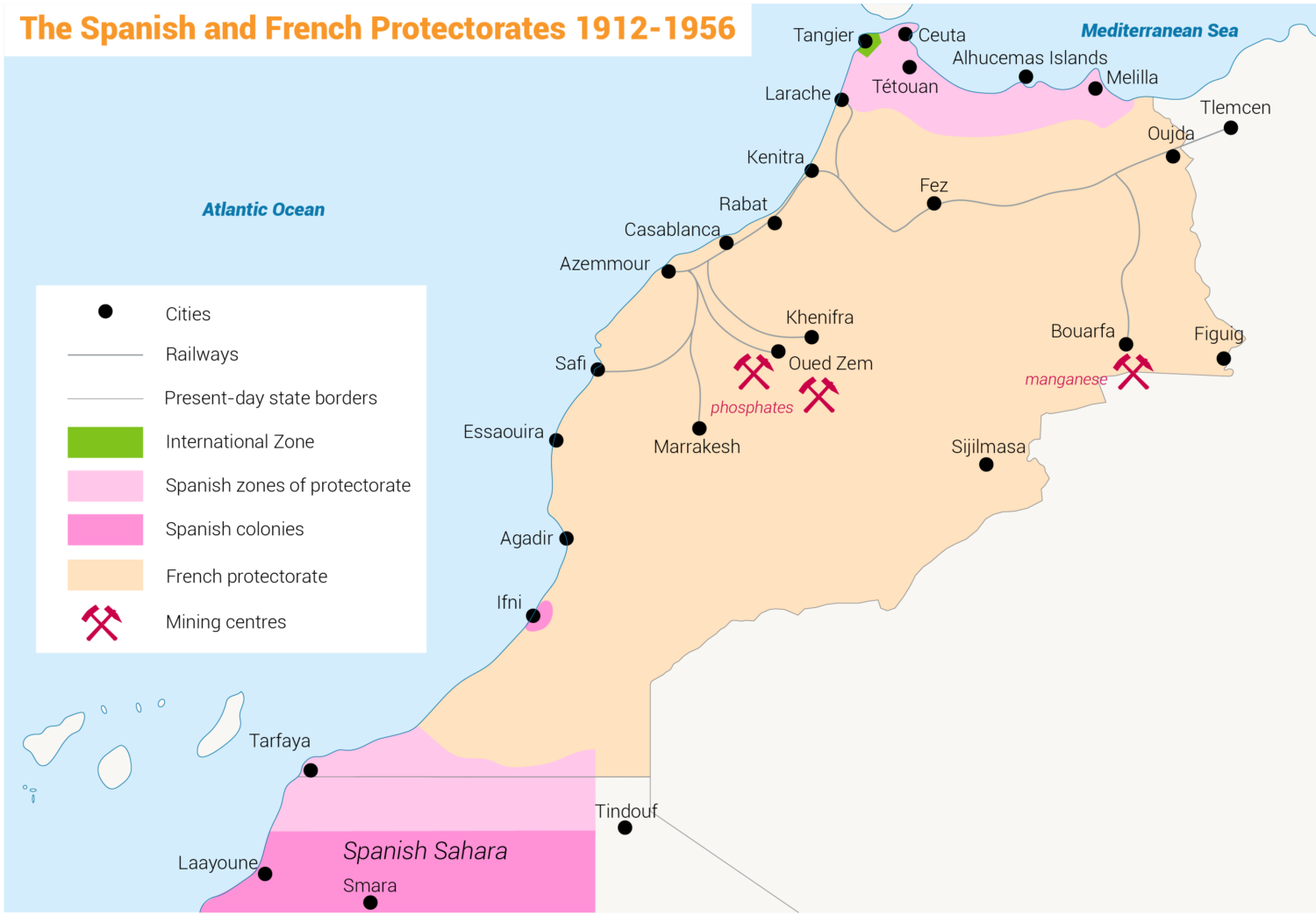

The colonial regime was not entirely French. In 1904, the French government had promised to preserve what they recognised as economic, strategic and political Spanish “interests”. Spanish troops already occupied some districts. Hence a ‘zone of Spanish influence’ (not a separate protectorate) was given to Spain. It included the mountains along the Mediterranean coast in the north, and a tranche of sandy territory around Tarfaya in the far south, around 43,000 square kilometres in total.

The Sultan remained the sovereign and therefore the historic Spanish enclaves on the Mediterranean coast, Ifni, and the territories of Rio de Oro and Saqia al-Hamra (the future Spanish Sahara) were excluded from the Protectorate.

The international consular corps had run Tangier since the mid-19th century, so in 1923 it became an international zone, still keeping the fictional sovereignty of the Sultan. Even so, the French authorities held the bulk of Morocco and established its modern infrastructure, administration and law.

General Lyautey

The highest French authority was the Resident-General. Paris appointed Hubert Lyautey, an experienced colonial general with clear ideas about how to govern the country. He began by replacing Abdelhafid with his brother Yussef, signalling the continuity of the Alaouite dynasty alongside French control.

But he had to conquer the countryside. At once, he faced a jihad in the south, led by a son of Ma’ al-`Aynan, Al-Hiba. He quickly defeated it, but not the more diffuse and determined opposition from the tribes in the Middle and High-Atlas mountains. The conquest was not completed until 1936.

Rif War

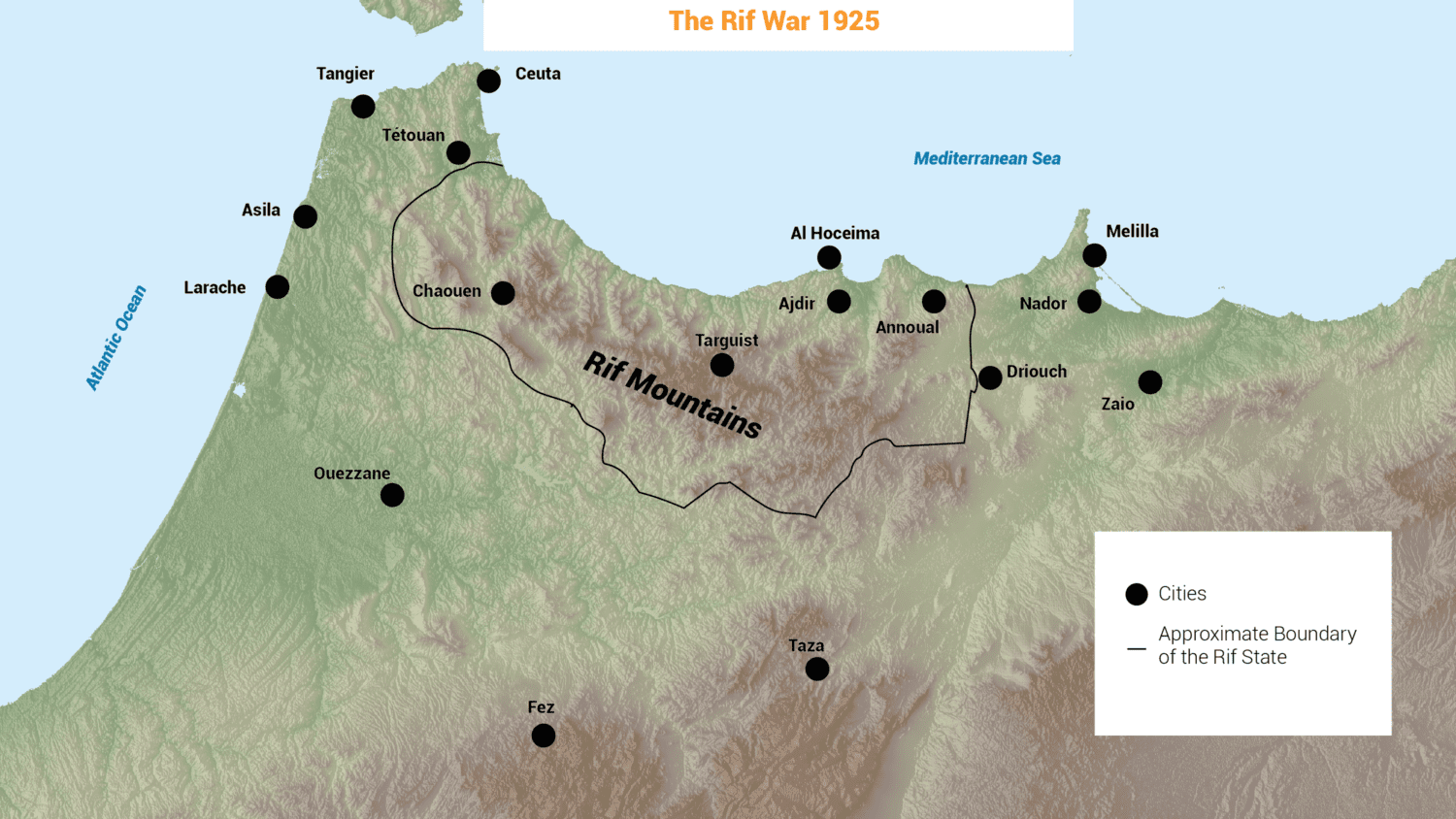

The most organised opposition was in the northern Spanish zone. During the First World War, the Spanish did little beyond recruiting many local notables as their agents. One was Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi, a qadi (Muslim judge) of the big central Rifi tribe of Beni Uriaguel.

He educated his eldest son Muhammad at the Qarawiyyin university in Fez, where he came into contact with the Islamic reformist Salafiyya movement. Muhammad then became qadi of the Muslim community in Melilla. When Spanish forces began their conquest, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim turned against the Spanish.

In 1919, Spanish troops advanced westwards from Melilla towards the central Rif and southward from Tetuan, occupying the holy city of Chaouen in October 1920. Ibn Abd al-Karim turned to the Beni Uriaguel to organise the opposition. He organised the nucleus of a modern army which overran the main Spanish base at Annual in July 1921 and massacred the Spanish troops that fled back to Melilla.

By the beginning of August, 13,000 had been killed. It was the worst defeat of a colonial army in the twentieth century. The Rifis captured huge amounts of military equipment and many Spanish prisoners whom they ransomed.

On that basis Ibn Abd al-Karim organised a small state, which he called the Republic of the Rif. It was founded on a combination of military success with the imposition of Islamic law, overriding tribal disunity. For five years, it was very successful – the Rifis defeated the Spanish again, at Chaouen in 1924 and invaded the French zone in 1925.

In September 1925, the Spanish and French armies united a huge landing army on the Rif coast to a French push northwards. In May 1926 Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim surrendered to the French, who sent him in exile to the island of Réunion.

French Protectorate

The French relied on a system of indirect rule to counter opposition, by incorporating local notables into their administration. The most prominent was Thami al-Glaoui who was Pasha of Marrakesh for forty years and kept the city loyal during both World Wars. He was notoriously corrupt.

Indirect rule was in line with General Lyautey’s ideas. He believed in advancing the Protectorate through policies that disrupted the pre-colonial system as little as possible, plus unequivocal force when needed. Thus the structure of the Moroccan government remained in place, controlled and shadowed by a parallel French administration.

The French built a modern economy in Morocco and roads, railways, and dams were constructed. An export-oriented and capital-intensive agriculture was largely reserved for French companies and settlers (colons) who occupied the best land. Only a very few favoured Moroccans entered the modern agricultural sector. Morocco’s greatest resource, phosphate mines, was nationalised; exports grew quickly, and by 1930 they provided for 17 per cent of state revenue. The local market was served by traditional and cash-strapped Moroccan agriculture.

The dual economy was parallelled by a dual society. Europeans lived in new modern cities while Moroccans did not. Lyautey designated a new political capital, Rabat, but made Casablanca the modern economic centre. His head architect, Henri Prost, designed villes nouvelles in the main towns and cities.

Prost modelled public architecture on traditional Moroccan styles masking European methods of building. The old medinas were reserved for Moroccans. As the Moroccan population of the cities grew, it spilled over into shanty towns, bidonvilles, on the outskirts.

Origins of Moroccan Nationalism

In accordance with the idea of indirect rule, French colonial theory divided Arabic from Amazigh speakers and emphasised French respect for ‘Berber values’. It created a separate ‘Berber’ legal system based on customary law. In 1930, this culminated with the famous Berber Dahir (decree) that formally divided the Islamic legal system from the customary ‘Berber’ systems. This decree excited nationalist opposition in the Arab-speaking cities.

In 1927 Sultan Yussef had died. His younger son, Muhammad V did not like the Berber Dahir, although he had to sign it. The protests brought him closer to the early nationalist movement. The French imprisoned two of its leaders, Allal al-Fassi and Muhammad Hassan Ouazzani, for their part in the protests. In 1934, they contributed to a nationalist manifesto, the Plan de Reformes that called not for the abolition of the Protectorate but its full application to the advantage of the Moroccans. The French still rejected it.

In October 1936, al-Fassi, Ouazzani and others formed the National Action Block (Kutlat al-Amal al-Wattani). The French swiftly prohibited it, but it reformed as The National Party for the Realisation of Demands (Hizb al-Watani li-Tahqiq al-Matalib). This was a modern reformist party, stridently loyal to the Sultan. Ouazzani split with Al-Fassi, and formed his own party. Within months, many of the nationalist leaders had been arrested and some were sent into exile.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Vichy French held the French Zone and Francisco Franco’s Spain controlled the Spanish zone. Some nationalists did make contact with Nazi Germany, but for tactical rather than ideological motives – there was no support for the persecution of the Jews.

The sultan refused to apply racist laws to the Jews. From the beginning, Muhammad V made it clear that he supported France and after the fall of France remained close to the Allies. When United States troops landed at Casablanca in November 1942, the sultan was immediately supportive.

In January 1943, the US president, Franklin Roosevelt, and the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, met at Casablanca. Although the sultan did not participate in the conference, he hosted a banquet at which Roosevelt apparently talked of Moroccan independence after the war. Moroccan nationalists close to the sultan also expressed strong liking for the United States.

Support for the monarchy and a pro-western orientation marked Moroccan nationalism. Even so, the Istiqlal party, which published its founding manifesto on 11 January 1944, included left-wing nationalists, like Mehdi ben Barka and other members of the trade union movement. The manifesto demanded a constitutional monarchy – an independent a democratic government under the sultan. Free French (a movement which fought against Nazi Germany), under General Charles De Gaulle, refused to consider such a scheme and the leading members of Istiqlal were arrested.

Approach of Independence

In 1956, Morocco achieved independence, eleven years after the end of the war.

In the intervening period the rapidly changing governments in Paris refused any idea of independence. The French settlers in Morocco fiercely resisted it.

Muhammad V took a leading position in the independence movement. In April 1947 he visited Tangier and made several speeches about Arab unity and Islam and its guarantee of justice. He praised the US government while attacking the French. The visit to Tangier showed how popular he was with Moroccans.

The French tried but failed to control him by relying on their old agents like Tuhami al-Glaoui, the Pasha of Marrakesh. Strikes led to attacks on Europeans, and some of the colons set up their own terrorist group. In August 1953, the French authorities deposed Muhammad V and exiled him to Madagascar. His replacement was an aged and unknown relative, Muhammad Ben Arafa.

Most Moroccans refused to acknowledge the new sultan, and protests and terrorist attacks continued. The French government concluded that the war in Algeria, which had begun in 1954, was more important and prepared to abandon the Protectorate. After a conference in Aix-les-Bains in France in August 1955 Muhammad V was allowed to return.

On 11 February, the French zone of Morocco became an independent state but the Spanish refused to return the northern and southern zones of their Protectorate to Morocco until 7 April and the Mediterranean enclaves, Ifni and the Spanish Sahara were excluded. The international zone of Tangier was abolished in July.