Introduction

Morocco had been peripheral to the Roman Empire – politically, economically and culturally.

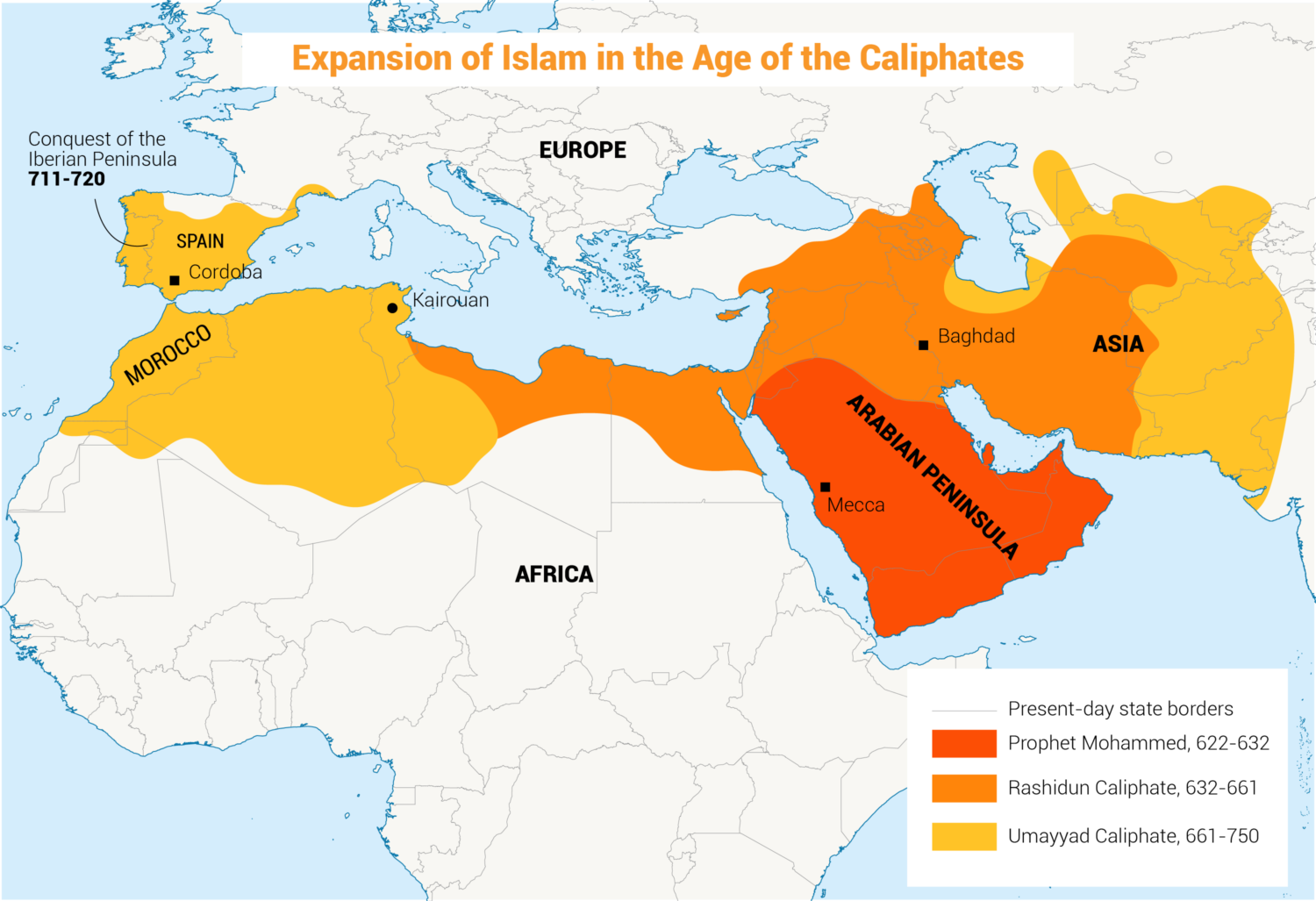

Islam originated in the Arabian Peninsula, where settled agriculture on the coast backed onto an arid interior. Like northwest Africa, Arab society was organised along tribal lines, defined by descent, and was basically polytheistic. The townspeople of Syria and Palestine, like those of North Africa, were often Christians or Jews. To the east of the Mediterranean, the inhabitants of the mountains and deserts spoke Semitic languages, while in Morocco they used varieties of Amazigh. Under Islam northwest Africa, would remain peripheral, but it was greatly affected by the major political events in the Islamic east, particularly the ideological and religious schisms.

The Prophet Muhammad was also a political leader who led a holy war against the polytheists of Mecca. He did not force Christians and Jews to convert to Islam; they were tolerated, provided they recognised Muslim rule and paid extra taxes. But Muhammad named no successor, and when he died, the Meccan elite was divided over who should lead the community as caliph. The split between Sunnis and Shiites would deeply affect the Maghrib for many centuries. Only when the Sunni Umayyads established the caliphate in Damascus in 661, could the conquest of northwest Africa begin.

The arrival of Islam

In 674 CE Uqba ibn Nafi founded a new base at Kairouan, in southern Tunisia. In 682 CE Uqba moved west, striking inland from Kairouan and outflanking the Byzantine garrisons on the coast.

According to legend, on reaching the Atlantic, he charged into the surf, crying “Oh God! If the sea had not prevented me, I would have coursed on forever like Alexander the Great, upholding your face and fighting all who disbelieved!”

Uqba’s triumph did not last. Many tribes rebelled, first led by a Christian Amazigh king, Kusayla, and then by a legendary warrior-queen known as al-Kahina (the priestess). For some years, the Muslim rulers abandoned Kairouan, but it was retaken in 691, and the last Byzantines on the coast were expelled.

Musa ibn Nusayr made Kairouan the capital of the province of Ifriqiya, its former Roman name. This new Islamic city, which began as a military camp, became a great centre of learning. By 710, Ibn Nusayr had taken Ceuta and Tangier and extended Muslim rule roughly within the line of the Roman limes, with three sub-provinces, in Tlemcen (modern Algeria), Tangier, and the Sous, in southern Morocco. The Arab governors had small Arab military contingents, but their armies were mostly Amazigh.

The Arab Muslims wanted trade, settlement and booty. They proclaimed a new revelation, but did not force Jews and Christians to convert. Some Amazigh tribes were Jewish and a few were Christian. Only those who were not monotheists could be forced to submit to Islam. There was Amazigh resistance, which the Muslims found hard to break, but many Amazigh converted willingly.

In 715, an Amazigh commander, Tariq ibn Ziyad, became governor of Tangier, and led a largely Amazigh army into the Iberian Peninsula. Gibraltar, Jabal Tariq, is named after him. Yet the Arab elite treated the Amazigh unequally, and many new converts aligned with heterodox movements.

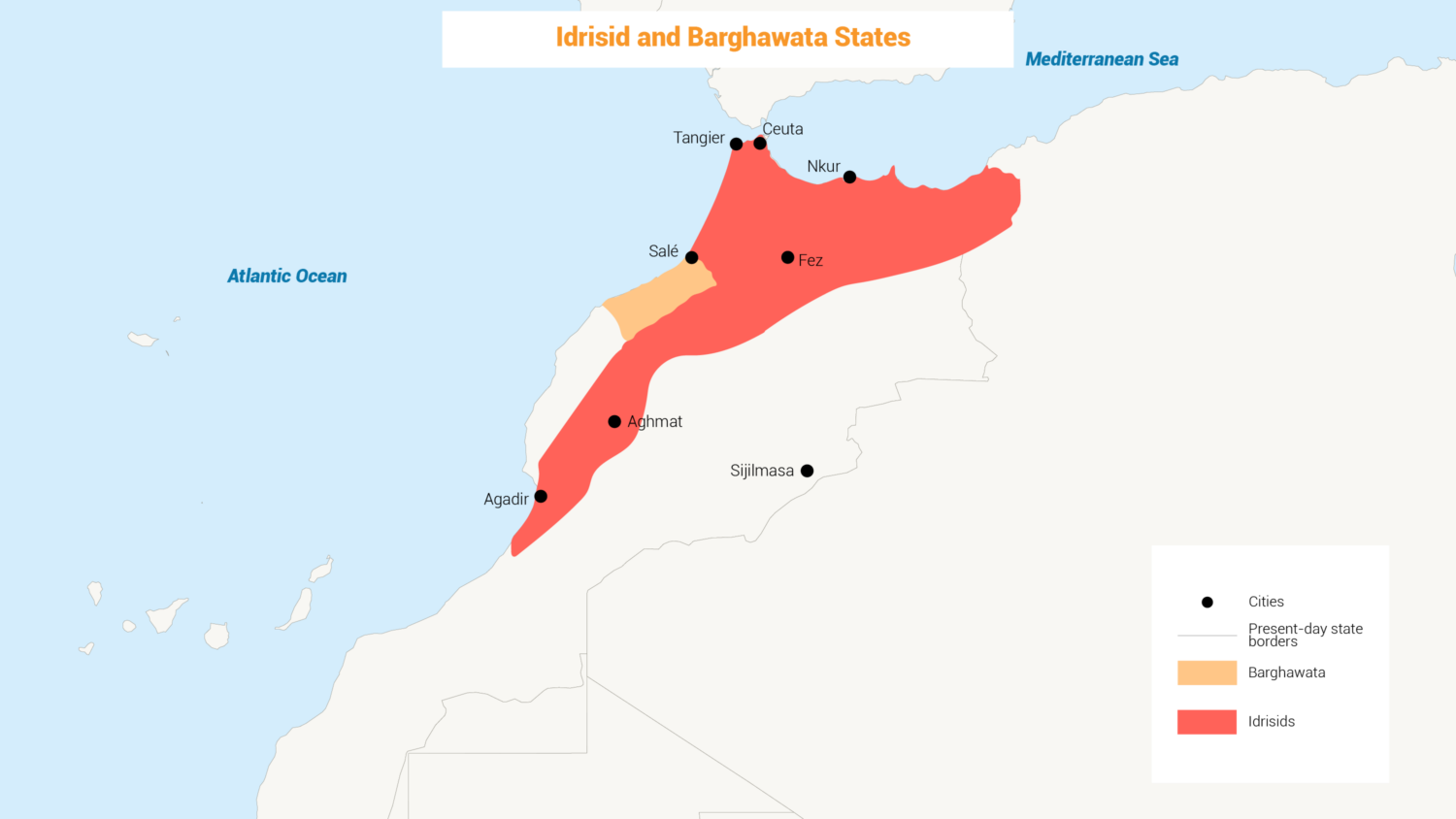

One such was Kharijism, a fiercely egalitarian movement holding that religious belief trumped social status. It rejected both Sunni and Shiite ideas and prized commitment to Islam above birth, racial or ethnic origin. After the Umayyads suppressed them in the Muslim east, many Kharijis sought refuge in Morocco. In 739 CE or 740 CE a rising in Tangier over taxation became a Khariji insurrection. The rebellion and its Amazigh leader – who called himself caliph – was put down, but Kharijism hung on in the mountains. In the mid-8th century, a Kharijite base at Sijilmasa, in the Tafilalt oasis system of southeastern Morocco, exploited the growing gold and salt trade across the Sahara. This helped spread Islam through southern Morocco and into the Sahara.

Another heterodox movement was entirely home-grown: the Barghawata had its base in the Atlantic plains and seems to have combined elements of Christianity, Judaism, and animism with Shiism. It had its own holy book influenced by the Koran (but written in Amazigh) and its own prayers and dietary laws; this movement lasted until the middle of the 11th century.

Shiism, the Idrisids and the foundation of Fez

The most important movement in the history of early Morocco was Shiite. Idris ibn Abdullah, a descendent of Ali (Prophet Muhammad’s cousin, son-in-law and companion) and Fatima, (the Prophet’s daughter) fled from the east and took refuge with an Amazigh tribe near Volubilis. In about 789, he built a base on the banks of the River Fez, and set up yet another petty state. Because it controlled the main road to the east, the Abbasid Caliph, Harun al-Rashid, had Idris poisoned. Idris’s unborn son survived, and in 803 the Amazigh people of the area proclaimed him sovereign. Idris II founded a capital next to his father’s settlement on the Fez River. By the time he died in 828, Idris’s state stretched from the Rif Mountains to the Sous, made rich by trade. Some modern Moroccan nationalists have claimed these events as the origins of the Moroccan state.

The Shia Idrisids were natural enemies of the Abbasid governors in Kairouan and of the rump of the Umayyads who settled in Iberia. Fez became an asylum for refugees. Religious scholars fled there after a uprising in Cordoba in 814, and in 824, refugees joined them from Kairouan. They brought mercantile skills and religious knowledge, wealth and intellectual sophistication.

Religious women from both communities, endowed great mosques: the Andalusiyyin, begun in 857, and the Qarawiyin (859), which is now the main university in Fez, and claims to be the oldest continuously functioning university in the world. Fez was marginalised politically, but grew rich from trade across the Sahara, and with al-Andalus (in modern Spain). As it prospered, Muslims and Jews arrived in large numbers, protected by new walls around it.

When Idris II died, his children divided the state and it slowly wound down. In the late ninth century, another Shiite movement in the Arab east, the Fatimids, failed and its followers took refuge in Sijilmasa. From there, they moved to Tunisia where, early in the tenth century, they built the capital of their caliphate at Mahdia. At the end of the century they conquered Egypt and moved the seat of the caliphate to Cairo. The Maghrib was marginalised once again from the Islamic mainstream. It was a battleground between three caliphates: the Fatimids, the Abbasids in Baghdad and the Umayyads in al-Andalus. Fez changed hands several times in these struggles but it prospered as traders artisans and scholars, Muslim and Jewish, poured in from outside.