Introduction

It is not possible to approach any culture without going back to its roots and sources. Let alone Morocco, as it has a distinct geographical location, which made it a major fulcrum for crossing civilizations with all their sciences and arts. A location that enhanced Morocco’s role as a forum for east, west, south, and north cultures. Even more, Morocco’s culture supported an entity of diverse ethnics such as Aamazighs, Muslim Arabs, Jews, Africans, Hassanis, and Moriscos.

In this context, Morrocan culture and all its various aspects should be viewed as the outcome of such a mixture between different cultures, and because of that Morocco formed its own special culture; as apparent in its architecture, ancient city walls, mosques and palaces.

Moroccan literature has its own specificity and a long ancient history. According to researchers, the dawn of Moroccan literature dates back to the Idrisian state that ruled Morocco during the second century AH [between the 8th and the 9th centuries]. Although it stumbled due to the competition with the eastern literature, Moroccan literature experienced a noticeable development during the following centuries, it kept up with times, adapting to each era of the Moroccan state, which had an impact on the variation in the degree of development and prosperity from one era to another

On the Moroccan soil, the prominent Judge Qadi Ayyad Ibn Musa was born, so was the exceptional scientist Ibn Bajja (Avempace) and Ibn Battuta, Ibn Khaldun assumed governmental positions, and on its soils, the philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes) walked and was buried there before his ashes were moved later to his hometown is Cordoba. The most well-regarded physician Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) spent the better part of his life in Morocco and was imprisoned for 10 years during Almoravid state by order of Ali ibn Yusuf Ibn Tashfin – Emir of the state.

Although Morocco’s history was rich in literature and intellect, the theatre was not a part of it until the 1920s, in a phase that was titled “Resistance Theatre”, then a second phase born on the independence eve and continued until the early 70s, where theatre became just an entertaining art in a phase named “in search for balance phase”, and it kept evolving to reach the phase of “theatre generation”, of which pioneers chose theatre as a profession in the 80s.

The special Moroccan music formed its clear features as Arab migrated to Morocco in the Islamic era, which had a prominent impact, enriching the Moroccan music as the Arab immigrant delivered Arab music, Yemeni music and Arab Gulf music mixed with effects of Persian music during trade convoys and military campaigns.

However, the cultural intermingling in the Moroccan culture with all its manifestations in architecture, modern fine arts and crafts remain the most evident.

To learn more more about the culture of Morocco, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Literature

It is difficult to identify a specific Moroccan brand of literature before the modern period. Historically, there was a deep tradition of scholarship in which writers born in Morocco and living there shared, but the subjects – law, religious commentary, philosophy, science – were the topics of a widerIslamic literature. Muslim writers of the classical age moved from place to place, while what would become Morocco was often part of a bigger political unit, as when Morocco was united with al-Andalus. Under the Almoravids (1040-1147), the scholar and Qadi Ayyad ibn Musa was born in Ceuta and worked in Granada before being executed by the Almohads, and Ibn Bajja, an extraordinary polymath, who wrote about astronomy, botany, philosophy, and music, was born in Zaragoza, in Spain, and died in Fes (also known as Avempace).

Although the Almohads (1147-1269) repressed their enemies, such as Qadi Ayyad, they also encouraged and sponsored scholars. The most famous was Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad Ibn Rushd (Averroës). He was born in Cordoba and died in Spain. Ibn Rushd was another polymath – in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, physics, theology, law, politics, music theory, and, above all, philosophy – whose commentaries on Aristotle were translated into Latin and had an important influence of mediaeval Christian scholasticism, but his works fell foul of the Almohads and were burned in public.

Other Almohad scholars include Ibn Zuhr (1094-1162) a physician and surgeon, and Ibn Tufail (ca. 1105-1185), a philosopher and novelist. Ibn Tufail’s philosophical novel Hayy ibn Yaqzan tells of a child raised by a gazelle, who lived alone on a desert island, before making contact with civilization through another castaway.

His ideas about the role of religion and reason in society found echoes in England after the book was translated in 1671, and they influenced the thinking of Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Another famous philosopher of Jewish descent was Maimonides (1135-1204), whose Misneh Torah is considered a hugely authorative codification of Jewish law.

The Marinid dynasty proper (1215-1420) produced two men who typify this cosmopolitanism, Ibn Battuta and Ibn Khaldun. Ibn Battuta (1304-1377) was born in Tangier and became one of the greatest travellers of all time. He set out on the hajj and spent most of the rest of his life travelling through Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Central Asia, South-East Asia, and China, over a distance estimated at more than 100,000 kilometres.

At the end of his life, he returned to Morocco and dictated his record of his journey, al-Rihla, to his secretary Ibn Juzayy. Ibn Khaldun was born in Tunis in 1332 and died in Cairo in 1406. He served as a state official in Fes, Granada, and Tlemcen and was a qadi in Cairo. His voluminous writings on history, including his famous Muqaddima, draw heavily on his experiences in state service as the basis for a theory of historical evolution that has been very influencial.

Neither Ibn Khaldun or Ibn Battuta wrote a specifically Moroccan literature: their philosophical and travel writings were much more a part of general Arab cultural movements, as were the works of poets such as Ibn Bassam al-Shantarini (d. 1147) under the Almohads, Ahmad ibn Abdallah Ibn Amira (d. 1259) under the Almoravids, and Ibn al-Khatib (d. 1374) under the Marinids. All three were born in al-Andalus. The same patterns existed under the Saadi sultans and the first Alaouis in the early modern period, but now a specifically Moroccan literature began to emerge in the form of local histories and biographical dictionaries.

The same patterns existed under the Saadi sultans and the first Alaouis in the early modern period, but now a specifically Moroccan literature began to emerge in the form of local histories and biographical dictionaries. Among the chronicles are the Nuzhat al-hadi bi-akhbar muluk al-qarn al-hadi of Muhammad al-Ifrani (1670-1745), and those of Muhammad al-Qadiri (1712-1773), both of which described tumultuous political events in a country riven by civil war.

Other political theorists, such as Abu Ali al-Hassan al-Yusi (1631-1691), sought to explain the disorder and prescribe solutions; al-Yusi acerbically attacked Sultan Moulay Ismail as a tyrant. The high point of chronicle literature came with the huge history of Morocco, Kitab al-Istiqsa li-akhbar duwal al-Maghrib al-Aqsa (Book of Inquiry into the history of the Maghreb states), by Ahmad al-Nasiri, who was born in Salé in 1834 or 1835 and died in 1897, just as Morocco was losing its independence under European pressure. His description of the final stages of state collapse is vivid.

Modern Literature

It was some time after the Protectorate was imposed in 1912 before a modern Moroccan literature appeared. The literary generation that lived through the Protectorate itself was small: only the poet Mohammed Ben Brahim (1897-1955), a native of Marrakesh, stood out, but his panegyric poetry for Mohammed V made him suspect to the French, and the analogous verses he wrote to honour Thami al-Glaoui made him a traitor in the eyes of the nationalists.

The generation after independence saw the emergence of a genuine modern Moroccan literature, often of a strongly nationalist colour: Abdelkrim Ghallab (born in Fes in 1917), the editor of the Istiqlal Party daily paper al-Alam who had studied at the University of al-Karaouine in Fes and at the University of Cairo, was a much-published and translated novelist. The official edition of his complete works runs to five volumes.

A more conservative figure was the poet and scholar Mohammed al-Mokhtar Soussi (1900-1963), who was Minister of Religious Affairs under Mohammed V. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Moroccan novelists began to publish, including Driss Chraïbi (1926-2007), whose most famous novel is Le passé simple (1954), and Mohammed Choukri (1947-1980). Choukri was an impoverished migrant from the Rif to Tangier, where he became the protégé of the American writer Paul Bowles, who was part of a group of expatriate writers living there in the 1960s (others were William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac).

Choukri wrote his first books with Bowles’ help, and they were published first in English and only later in Arabic and French. Works include al-Khubz al-Hafi (For Bread Alone). Chraïbi, like many of his generation, published entirely in French.

An important influence on Moroccan literary life was the magazine Souffles, which began as a poetry journal in 1966 and eventually covered painting, cinema, theatre, essays, and other writing. It was banned in 1972, and one of its founders, the poet Abdellatif Laabi (b. 1941) was imprisoned, tortured, and exiled to France.

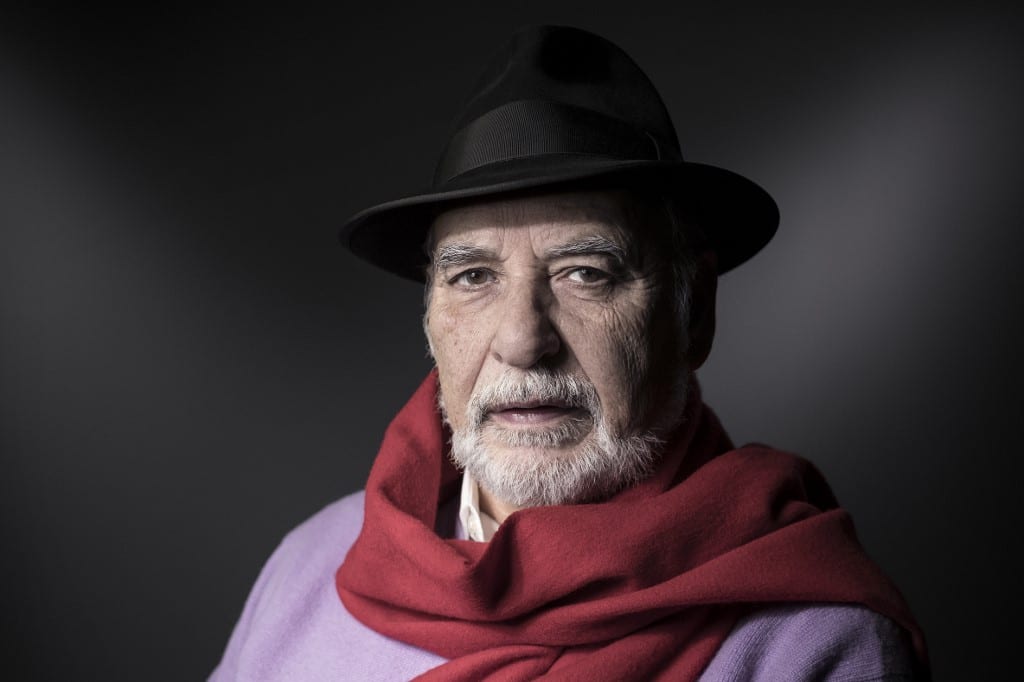

Tahar Ben Jelloun (b. 1944), whose earliest fictional work dates from the 1980s, also writes entirely in French. His novel La nuit sacrée (The Sacred Night) won the Prix Goncourt in 1987 and has been translated into more than 40 languages. His Cette aveuglante absence de lumière (This Blinding Absence of Light) won the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2004. In 2008, Ben Jelloun, who lives in Paris, was awarded the highest French decoration, the Légion d’Honneur.

Not all modern Moroccan literature is in French: there are several important writers in Arabic. Mohammed Achaari (b. 1951, in Moulay Idriss Zerhoun) has published short stories, poetry, and a novel, al-Qaws wa al-farasha, (The Arch and the Butterfly) that was joint winner of the 2011 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Bensalem Himmich (b. 1948 in Meknes) is a novelist, poet, and philosopher. His novels Majnun al-hukm (Le fou du pouvoir) (1990) won literary prizes and al-Allama (The Polymath) (2001), a novel about Ibn Khaldun, won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature.

Film, Theatre, and Television

There is a long tradition of street theatre in Morocco. In the halka (literally ‘circle’) several performers gather around a narrator and act out the story. Venues such as the Jamaa al-Fnaa in Marrakesh attract large crowds. Many of these halka performances have a comic intent, often to make a social or political point.

During the colonial period, dramatic groups from Egypt visited Morocco, and there were theatre productions for the European community. One of the most famous colonial theatres was the Gran Teatro Cervantes in Tangier, built in 1913 with a splendid art-deco facade. It is now unused and dilapidated, although there is a Spanish government project to restore it. It was not until after independence that formal theatre was popularized, first by the radio and then on stage.

In 1962, the first theatre, the Théâtre National Mohammed V, was opened in Rabat. In the 1980s, university theatrical groups developed, and the Institut Supérieur d’Art Dramatique et de l’Animation Culturelle (ISADAC) was founded in Rabat. The Théâtre National Mohammed V is now a venue not only for theatre but also for opera, ballet, and musical performances.

There is an annual Berber theatre in Casablanca in May, which includes mime, masks, and puppetry, as well as formal theatrical performances. The annual Marrakesh Popular Arts Festival (Festival National des Arts Populaires) in June or July, includes entertainers and artists from Morocco and abroad including singers, snake charmers, dancers, acrobats, and musicians, as well as formal theatre performances.

Modern Moroccan drama, like other Moroccan literature, is written in both Arabic and French. Tayeb Seddiki writes in both languages and was a major force in founding radical theatre groups. Ahmed al-Tayyeb Aldj not only writes in Arabic himself but has translated Molière, Shakespeare, and Brecht into Moroccan Arabic.

Félix Mesguich has been credited with bringing the movie camera to Morocco in 1907. Mesguich, who was born in Algeria and served as a French colonial soldier, was an early collaborator with the brothers Lumière, who toured the world with their Cinématographe between 1906 and 1910. But it was not until 1919 that the first feature film was made in Morocco. Several dozen more were made between the two world wars. After World War II, Morocco began to be seen as a venue for foreign film-producers: Orson Wells filmed parts of Othello (1952) in Morocco.

The first authentically Moroccan film dates to the early 1950s, when Mohammed Ousfour began filming, making Moroccan versions of Robin Hood and Tarzan as shorts. He also made the first Moroccan feature film Le fils maudit in 1958. The Moroccan film industry grew slowly. The Dictionary of African Filmmakers identifies one or two films a year in the 1970s, but the industry grew rapidly in the 1980s, assisted by state funding through the Fonds d’Aide à la Production and the Fonds d’Aide à la Production, which were, by 2004, making grants totalling USD 4.4 million.

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, a dozen or so feature films and a few additional short films were being produced each year by producers such as Mostafa Derkaoui and Abdallah Mesbahi (Abdellah Masbahi). During this period, Ouarzazate became a centre of the Moroccan film industry, partly because foreign film-makers filmed there, for example, Martin Scorsese (Kundun), Ridley Scott (Gladiator and Kingdom of Heaven), and Tony Scott (Black Hawk Down).

Music

Moroccan music reflects the country’s position as a meeting place of Berber, Arabic, and European cultures. Traditional Berber music uses wind instruments such as an end-blown reed flute (taghanimt), bagpipes (mizwid), and a trumpet (nafir); stringed instruments such as the ginbri, which has a long fretless neck, with the box covered in skin, and the rebab, a long-necked fiddle with only one string; and percussion instruments such as the tabl, a cylindrical double-sided drum, and the qaraqib, a metal castanet-like instrument.

Berber music has several functions. One of them is traditionally to preserve a record of the past: Berber songs have repeatedly been used to uncover details of past events in a largely oral tradition. Music is also used in village celebrations and on religious occasions. Professional musicians perform, for example, at weddings or as street artists in venues such as the great Jamaa al-Fnaa square in Marrakesh. It is highly regionalized, and southern Berber music has strong Sahara African influences.

The Hoba Hoba Spirit of Moroccan Music

Hoba Hoba Spirit is a Gnawa fusion band that burst onto Morocco’s musical scene in 1998 and has been delighting young audiences in the north African country and beyond ever since. In 2008, the New York Times described them as a ‘crowd-wowing, multilingual Maroc ‘n’ roll band’ and in 2010, the Guardian called them ‘a furious post-punk guitar band’.

They are often considered a mouthpiece of the rebellious new generation in search of an identity in the face of obscurantism and Islamic radicalism that currently plagues Arab societies.

The group sings in French, English and Darija (a Moroccan Arabic dialect) and mixes rock and hip-hop with an energizing form of oriental dance. It is for this reason that the group has been nicknamed ‘the Moroccan Clash’.

Since 2003, Hoba Hoba Spirit has attracted an increasing number of young fans. It is now one of the most popular rock acts in Morocco, frequently playing its major festivals, such as the Mawazine Festival in Rabat, L’Boulevard Tremplin in Casablanca, Timitar Festival in Agadir, and the Gnawa and World Music Festival in Essaouira. It is at the latter that the band has had most success.

In 2007, Hoba Hoba Spirit won three Maghrib Music Awards for best fusion artist, best album for Trabando and best title for the song ‘Fhamator’. In addition, it has given more than 400 concerts in Morocco and beyond and toured the United States in 2014, cementing its reputation. Its seventh album was released in 2016.

There are several reasons for Hoba Hoba Spirit’s popularity: it uses cultural icons that speak to young people; it fuses various musical styles; and it is composed not only of musicians but also of a journalist and social critics such as Reda Allali. The other band members are Anouar Zehouani, Adil Hanine, Saad Bouidi, Othmane Hmimer and Abdessamad Bourhim. All six are from Casablanca.

The band’s success is due also to the democratization of the media, thanks to the spread of the internet and the ability to access information and build networks across national, religious and social boundaries. The increasingly globalized world is another factor in the group’s visibility.

But the real reason for their popularity is that they simultaneously appeal to ordinary Moroccans and link them to universal themes. Their lyrics are well chosen. For example, when they sing ‘we live in a permanent collective delirium’, they reach people because they sing the way they speak and perform what they feel. This emotional openness and the energy with which it is conveyed are contagious.

Hoba Hoba Spirit’s music has also been influenced by the Arab Spring and its aftermath. It is loud like the voices of the millions of people who took to the streets demanding karamah (dignity), and the ‘fearlessness’ of the lyrics and movements are reminiscent of Bob Marley, The Clash, but most importantly of Morocco’s ancient Gnawa rhythms.

Vocalist and guitarist Allali explained Hoba Hoba Spirit in the following terms: “It is a release of the body, the heart and the soul in a spontaneous and chaotic mixture. It is the will to do something that has a strong impact on the moment without worrying about the image or the rest. We want to change this time, we want people’s heart to beat faster, we want them to sweat, we want them to think that the best place in the world is here, is now. It is this spirit that drives us to feel that we can push back the walls.”

A number of other musicians are now imitating or fusing their music with Hoba Hoba Spirit’s, like the popular singer Abdelaziz Stati, who collaborated with the band on the track ‘Wakel Chareb N3es’ in 2010. The collaboration was well received especially in the cosmopolitan city of Casablanca.

The success of Hoba Hoba Spirit is also a victory over fear, as guitarist Anouar Zehouani explained: “The greatest difficulty has been mental, that is to say, how to overcome this situation where we say that everything is difficult, nothing is possible here in Morocco. But once you exceed the limit, everything is possible!”

Architecture

The UNESCO World Heritage Listing for Rabat (2012) describes the city as ‘the product of a fertile exchange between the Arabo-Muslim past and Western modernism’.

That is a fair description of the architectural history of Morocco as a whole. Included in the Rabat listing are the new town, built during the French Protectorate to house administrative, residential, and commercial areas, alongside botanical and pleasure gardens and in the shadow of the remnants of the Hassan Tower (begun in 1184) and the

Thus, the listing for Rabat covers most of the principal stages of Moroccan architecture, with three exceptions: the Roman period, the impressive modern architecture of independent Morocco, and the modern bidonvilles (shanty towns) that surround Rabat (and all other Moroccan cities).

Roman Period

The only extensive examples of Roman architecture are at Volubilis, another World Heritage Site (registered in 1997). Volubilis was a fortified Roman municipium on a commanding site of 42 hectares at the foot of the Jabal Zerhoun, near Meknes, although it also predates and postdates the Roman period. Volubilis was occupied for about a thousand years, ending in the early Islamic period as the first capital of Idris I in the late 8th century, before he transferred the Idrisid dynasty’s capital to Fes. The ruins are surrounded by ramparts and contain an impressive triumphal arch.

Early Islamic period

Little architecture remains from the early Islamic period. Idrisid Fes has largely vanished, although the Andalusiyyin and Qarawiyyin quarters and their accompanying great mosques indicate the outlines of the Idrisid city (see the Medina of Fes at UNESCO).

Almoravid and Almohad periods

The architecture of the Almoravid period is also difficult to find: although the city plan of Marrakesh is Almoravid, there is little to show for it apart from a few ruins and the qubba (domed tomb) of the Ben Youssef Mosque. The Almohads destroyed much Almoravid architecture across Morocco, and their architecture is prominent, as seen in Marrakesh in the city walls and gates and the Koutoubia mosque, whose square minaret was the model for the Tour Hassan minaret in Rabat, the Giralda in Seville, and countless other mosques across Morocco (see the Medina of Marrakesh at UNESCO).

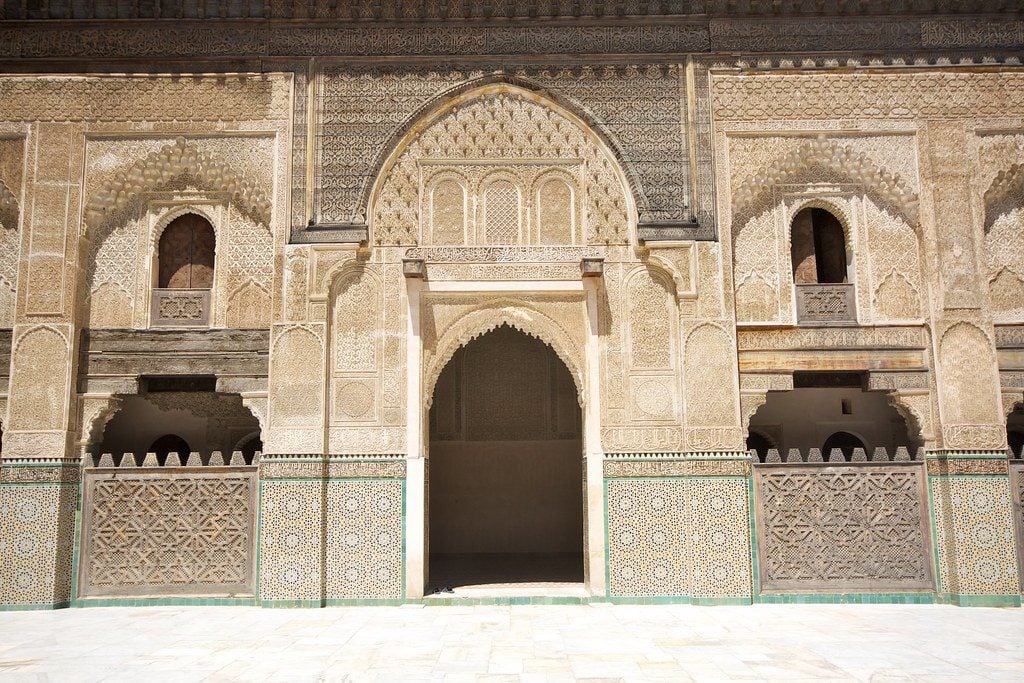

Marinid period

The Marinids were responsible for building New Fes as a military and administrative centre, and much of Marinid architecture is military, for example, the massive city walls in Fes and Salé, and the abandoned city of Chella outside Rabat. Their other important buildings were madrasas: the Seffarine in Fes, and the Bou Inania, in Meknes, with its elaborate decorative plasterwork, are fine examples.

16th-19th centuries

The most important Saadi structures are the tombs and the Badi Palace in Marrakesh. During this period, many refugees from al-Andalus brought new architectural styles; their houses are found especially in the medinas of Tétouan, Rabat and Fes. The numerous palaces of the sultans and the Moroccan elite date from this period; many of the more interesting ones are now museums.

Colonial period

When the French took over their Protectorate, Marshal Lyautey insisted that new European-built suburbs would introduce European ideas of urban planning while preserving historic monuments and traditional housing and using Moroccan motifs, where possible, in the new buildings. Thus, the past was re-appropriated and used in an architectural and decorative synthesis that set modern public spaces and landscaping alongside the older medinas. The best examples are in Rabat, Fes, and, especially, Casablanca, a city that was rebuilt almost entirely by Henri Prost, Lyautey’s chief architect.

Independent Morocco

Modern Moroccan architecture has continued the colonial synthesis to a limited degree. Large-scale modern developments, such as hotels and apartment blocks, look much like similar buildings elsewhere. Their sleek designs do not resemble older Moroccan styles of architecture, but the interior decoration of their public and common spaces is often heavily dependent on Moroccan designs. At the same time, a self-consciously nostalgic ‘Moroccan’ style had become popular through the fashion of renovating riads (elaborate town houses) in Marrakesh and elsewhere. This style is now becoming popular in domestic architecture in Britain and the United States.

Bidonvilles

The architecture of the bidonvilles has been little studied: it is based on appropriating sites and materials from formal urban spaces and reusing them without reference to official architectural styles, state and public facilities, or official control. Dilapidated housing and few paved roads, utilities, or public services have thus been accompanied by a lack of government interference. The political problems of the 1990s and 2000s led the state to try to remove bidonvilles and replace them with publicly controlled housing, which many inhabitants find even less attractive. Traditional rural architecture is confined to domestic and mosque architecture. Domestic styles vary according to region and physical conditions. Mosque architecture has developed considerably as a result of emigration: eastern Arab styles, especially minarets, have become much more common.

Visual Arts

During the colonial period, many European painters settled in Tangier, forming an Orientalist school. Towards the end of the Protectorate, a number of Moroccan artists, such as Mohammed ben Ali R’bati, Abdelkrim Ouazzani, and Moulay Ahmed Drissi began to emerge. Abstract artists such as Ahmed Cherkaoui (1934-1967), who was fascinated by calligraphy, and Jilali Gharbaoui (1930-1971) both studied in Paris, but the establishment in Tétouan of the École des Beaux Artss in 1945 and another school of the same name in Casablanca in 1950 gave a great impetus to Moroccan art.

In the early 1960s a handful of young Moroccan artists, all men, at the École des Beaux Arts in Casablanca started a movement that mixed European and Moroccan influences. The Casablanca School was a crucial element in the birth of contemporary Moroccan art, providing a totally new and contemporary indigenous style of art.

Among contemporary artists influenced by this school are Malika Agueznay, Tibari Kantour, Rim Laâbi, and Mimouni Hassan.

Another group of painters emerged in Tangier in contact with the American expatriate artists and writers who lived there in the 1950s and 1960s; those included Mohammed Mrabet(b. 1936), Ahmed Yacoubi (1931-1985), and Mohammed Hamri (1932-2000).

Among the most important galleries are the Galerie Nationale Bab Rouah, the Galerie Mohamed El Fassi, and the Galerie Bab El Kébir in Rabat, the Galerie Mohamed Kacimi in Fes, the Galerie Bab Doukkala in Marrakesh, and the Galerie d’Art Contemporain Mohamed Drissi (formerly the Musée d’Art Contemporain) in Tangier. The online exhibition Art Maroc has more than 1,500 reproductions of paintings by modern Moroccan artists.

Cultural Festivals

Following the 2003 suicide bombings in Casablanca, Morocco embarked on counter-terrorism reforms in order to confront such threats. In 2011, the Moroccan king, Mohammed VI, undertook political reforms meant to accommodate both Islam and democracy. Its current government, under the leadership of the Justice and Development party, is today the only Islamist government in North Africa.

Morocco’s consistent efforts to defeat terrorism resulted in the dismantling of 47 terrorist cells between 2013 and 2015, eight of them in 2015 alone. Yet, according to the latest figures from the Moroccan Interior Ministry, there are about 1350 young Moroccans fighting alongside the extremist Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq, and many are fighting with affiliates of IS, al-Qaeda, and other organizations.

While the security and political measures are critically important, culture and art play an equally vital role in immunizing Moroccan society against violent extremism. Violent extremism, as demonstrated by the recent actions of IS in Syria, Iraq, and Libya, has declared war on culture and on any interpretation of Islam that differs from its own.

Morocco’s international cultural festivals are fighting back by declaring war on intolerance and rejection of the “other,” regardless of their background, and by embracing diversity. Such festivals also combat some of the causes of violent extremism, such as the marginalization of youth, ignorance of the “other,” poverty, and unemployment.

Morocco stages more than a hundred festivals each year, encompassing all its regions and embracing all its religious and cultural diversity. Some of these festivals are global, attracting millions of tourists and the world’s finest artists. These include, for example, the Mawazine festival of Rabat, the Essaouira Gnaoua Festival, the Fès World Sacred Music Festival, and the Marrakech du Rire Comedy Festival.

Such festivals not only bring together different cultures and peoples around a cultural consensus of the universality of art but also celebrate the Moroccan nature of tolerance and acceptance of the “other” that is drawn from its position as a historic meeting place of various civilizations. They are a gentle reminder of the essence of a multi-cultural and religiously diverse Moroccan society and thus constitute a defence against all forms of extremism that expound the exclusion of people for their differences.

Mawazine Rhythms of the Worlds

Since its inception in 2002, Mawazine has striven to satisfy the diverse musical tastes of its spectators by bringing together the most renowned Moroccan, Arab, and international music performers. In doing so, it portrays Morocco’s capital, Rabat, as a capital of “diversity, tolerance, and sharing.” Multiple stages and free admission to shows guarantee that the festival reaches those who are not well off.

Mounir el Majidi, the president of the Mawazine Festival, sees the festival as “a symbol of a Morocco with intrinsic values of openness, diversity, sharing, and respect for cultures.

Mawazine also sends a strong message to the Moroccan youth: the cultural wealth of the Kingdom awaits them and all can benefit. Hence, they can be proud of the nation’s priceless heritage and of its principles of tolerance, which form the foundation of our past, our present and our future.”

According to mtviggy.com, Mawazine (“Rhythyms”) is the second largest music festival in the world. In 2015, it attracted more than 2.6 million spectators, 40 million TV viewers, and 130 shows. The festival generates 3000 jobs and a 22 percent growth in tourism revenue in Rabat.

Essaouira Festival: Gnaoua and World Music

The Essaouira Festival has taken place for 18 years and it is meant to celebrate Morocco’s African heritage and fuse its music with other styles. Gnawa (Gnaoua) music is most popular in West and North Africa. Historically, during times of slavery, Gnawa music included, among other things, the prayers of slaves seeking mercy.

The style still has spiritual links, and many Gnawa enter trances to heal themselves or others. For the 250,000 people who visited the festival this year, however, Gnawa music is more about joy, colour, and “fusion” with other music and cultures captured in the lively dances of singers and spectators. The organizers of this year’s festival wanted it to counter IS’s hostility towards culture by showing another side of Muslims.

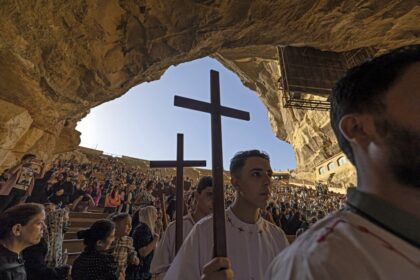

Fès’World Festival of Sacred Music

Fès is a city known for its rich cultural and religious heritage, due in large part to its history as a commercial hub for traders coming from Africa. As Abderrafia Zouitene, the president of the World Festival of Sacred Music, put it, “this flow of both merchandise and people across the desert expanse allowed for the transmission of ideas, manuscripts, social conduct and understanding of previously unknown magnitude.”

This allowed Sufi masters from across Africa to debate and share ideas. During the 21 years of its existence, the festival has embraced the spirit of dialogue of civilizations and tolerance towards other religions, beliefs, and even the various interpretations of Islam.

Marrakech du Rire, Comedy Festival

The festival Marrakech du Rire (“Marrakech of Laughter”), which brings together comedians from different backgrounds, mainly Africans and French, is now in its fifth year. In 2014, it attracted 70,000 spectators and 70 million TV viewers. Its popularity is driven by its relatively low ticket prices, its presentation in in both French and Arabic, and its use of public spaces in Marrakech for staging shows.

The festival is yet another vehicle for promoting tolerance of other cultures. The jokes are often provocative, intended to defy stereotypes on religion, race, sexual orientation, and more. In Marrakech du Rire, people come to laugh at their own shortcomings and prejudices, and they leave in a spirit of joy and self-critici.

Controversy

Festivals display a happy, modern Morocco in order to shape international opinion about the country and attract investors and tourists. Some Moroccans struggle, though, to see the benefit of allocating public funds to already rich international artists. Many think the money should be spent on direct investment in the country’s developmental projects in order to affect ordinary Moroccans directly. Critics sometimes criticize sexually suggestive dances and songs, mainly from Western performers, because they conflict with Moroccan values of modesty and respect.

Crafts

In recent years, small-scale artisans have struggled to survive in Morocco. They have been faced with the impact of globalization, the difficulties of transporting their production to markets, and a declining interest in handicrafts among modern Moroccan consumers. The government has acted to improve and foster the handicraft sector because it has long been a major source of national income: Moroccan artisanry is justly famous, particularly in carpets, pottery, and leatherwork.

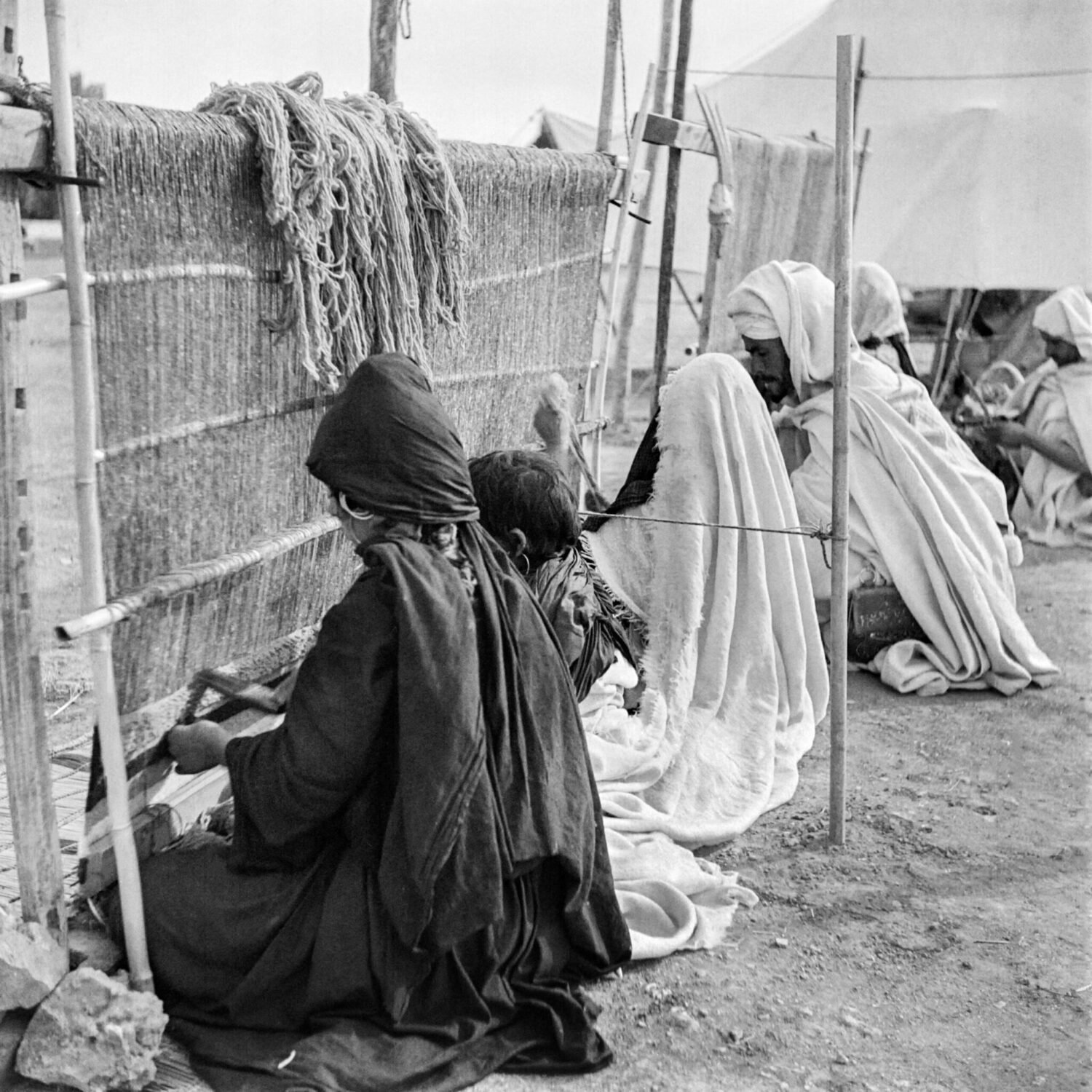

Carpets

Moroccan carpets have long been popular throughout the world. In 1829, Edward Drummond Hay, the British Consul in Tangier, was repeatedly given carpets by important local officials as a mark of their respect. Later in the 19th century, there was a boom in carpet production, supplying both the growing local market as merchants enriched themselves with trade, and middle-class consumers in Britain and France. Under French rule, the Native Arts Service worked to preserve traditional techniques and to create new artistic forms that could be incorporated into a modernist aesthetic.

There are two main types of Moroccan carpet, those produced in cities and those that originate in Berber areas. The most celebrated urban designs come from Rabat and may have originated in either Asia Minor or Andalusia, as many refugees from the Christian Reconquista settled in Rabat and Salé. The earliest known examples go back to the seventeenth century. Berber carpet- and rug-design seem to be more ancient, and their motifs vary widely, by region. Today, these regional deigns are defined by the Direction de l’Artisanat, which certifies their authenticity and licenses them for export.

Both the urban and the Berber carpets are high-quality knotted carpets made of wool, with a backing (warp) of wool or cotton or sometimes silk. Another floor covering is the kilim, a woven rug, much cheaper and lighter and often in more vibrant colours. These are not so extensively controlled.

The export of carpets is of great value to the Moroccan economy, although it is declining fast: the value of carpets exported from Morocco in 2000 was only 44 percent of what it was in 1990, although it constituted the largest proportion of the artisanal exports by far (32 percent in 2000). Other types of Moroccan artisanry have weathered the economic problems better than carpets: exports of pottery, jewellery, and leather work all increased during the 20th century.

Pottery

As with carpets, there are two main sorts of pottery in Morocco, fine urban designs and rural patterns, some of the latter very naïve. The urban ware of Fes, Meknes, and, above all, Safi, is highly glazed and coloured. Safi designs seem to have been influenced by designs originating in al-Andalus (particularly the region around Málaga) and are characterized by a metallic sheen. Fes is noted particularly for blues and greens on a white background. In rural pottery the dominant colour is often ochre (especially in the High Atlas) or green. In the northern regions of the Jebala and Rif, pottery made from rough red clay is decorated with embossed patterns rather than being glazed.

Jewellery

Jewellery was formerly a Jewish tradition in Morocco, but Muslims now manufacture all of it. Gold is essentially an urban production, heavily influenced by designs from Muslim al-Andalus, while silver is essentially a rural production influenced by Berber designs. Gold and silver both served historically as stores of wealth, but only richer city dwellers could afford gold.

Leatherwork

The French word for leatherwork is maroquinerie: it is quintessentially Moroccan. Tanning is an important industry in Fes, which provides over half of the leather used in Morocco. With the exception of slippers (yellow or white for men, embroidered and brightly coloured for women), most Moroccan leatherwork is intended for tourist markets or for export.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport. Morocco qualified for the FIFA World Cup five times, the latest of which was in the 2018 World Cup in Russia, after 20 years of absence. In October 2020, Moroccan’s national football team ranked 39 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

The Moroccan people have their special way of showing love for sports. They are excellent at different types of sports such as the equestrian sport, swimming and athletics. Hicham El Guerrouj won two gold medals at the 2004 Summer Olympic Games in Athens.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Morocco’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: