Introduction

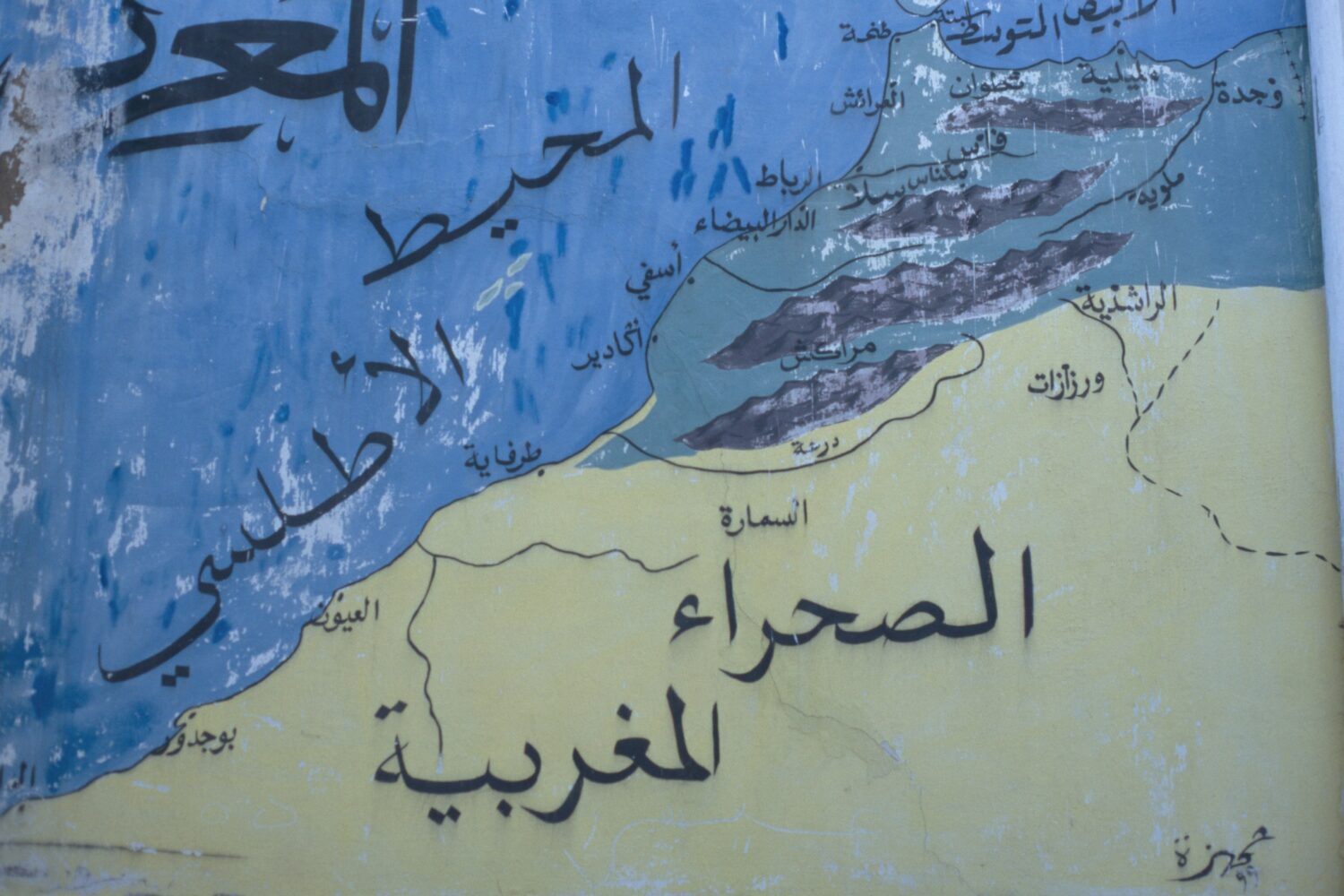

Morocco was enormously rich in phosphates. So was the Spanish Sahara, and the opportunity to create an export monopoly was one consideration behind King Hassan’s great political project from the mid-1970s: to incorporate the Spanish territory. Another motivation was the long-standing nationalist claim to territories stretching far to the south. Diplomatic negotiations had already persuaded the Spanish government to abandon the tiny territory of Ifni in the far south of Morocco in June 1969. After Franco died, the new Spanish government lacked the will to hang onto the Spanish Sahara.

In 1973 a group of Saharan students set up a nationalist movement, the Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguia el-Hamra y Río de Oro (POLISARIO). It soon began attacking remote Spanish military posts and then, in October 1974, POLISARIO sabotaged the conveyor belt to the Bu Craa mines and stopped the export of phosphates. Realising that it would be impossible to hold onto the Sahara, the Spanish government insisted on ‘self-determination’ for the colony, with a referendum to include the option of independence. Neither the Moroccan, nor the Mauritanian governments supported the move.

Secret Deals

King Hassan and the Mauritanian President, Moktar Ould Daddah, secretly agreed to divide Western Sahara after the Spanish left.

Hassan also asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to rule on the legality of Moroccan and Mauritanian claims to sovereignty. Was the territory ‘terra nullius’ (subject to no state) when the Spanish colonised it? If it was not, what legal ties linked its inhabitants with those of Morocco and Mauritania?

Moroccan lawyers argued for a historic religious allegiance to the sultan. The Mauritanian government said there was a common historic identity between the tribes of the two territories. Because the Spanish government refused to accept the ICJ’s jurisdiction, the court could give only an advisory opinion, not a judgement.

In October 1975 the ICJ opinion found that the historic links between Morocco and Mauritania and the inhabitants of the Western Sahara were not ties of sovereignty, so the population had the right to self-determination.

The Green March

King Hassan moved quickly to undermine the judgment. In November 1975, his government organised a ‘Green March’ across the border to claim the colony. Over half a million Moroccans took part: the claim to the Sahara was clearly a popular one in Morocco.

Imposing Moroccan Rule on the Western Sahara

Although the UN Security Council passed resolutions deploring the March, King Hassan made an agreement with Spain and Mauritania making the northern part of the colony Moroccan and the southern part Mauritanian. By 12 January 1976, Moroccan troops and the tiny Mauritanian army had occupied their allotted areas.

POLISARIO could not stop them, and with Algerian help, began a guerrilla campaign from its bases in the refugee camps in Tindouf, just across the Algerian border. On 26 February 1976, Spanish rule ended. A Saharan Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), based in the refugee camps was recognised by the Algerian government, which supplied weapons and training and several Sahraoui tribes, by some estimates almost half the population, moved to the camps to join them.

The Mauritanian army soon gave up, and, in 1979, the Algerian government brokered an agreement under which Mauritania dropped all its claims. Moroccan troops then occupied the Mauritanian zone.

Algeria and Libya were the only Arab states to support POLISARIO diplomatically. However, the guerrilla campaign was very successful. POLISARIO disabled the phosphate-rock conveyor belt and attacked Laayoune. During the next two years, POLISARIO expelled the Moroccan army from inland posts and even operated far into Morocco itself. They could not force the Moroccan forces to leave, but guerrilla attacks on the Mauritanian capital, Nouakchott, and the iron mines that provided most of the national income, drove Mauritania to bankruptcy.

In July 1978, the army overthrew the Mauritanian president Ould Daddah and then accepted a cease-fire offer from POLISARIO. In April 1979, after another coup, the Mauritanian government recognised POLISARIO as the ‘sole legitimate representative of the Saharan people’, and renounced its claim. The Moroccan army moved south and occupied the rest of the former Spanish colony.

Moroccan Control of the Western Sahara

To cope with the increasingly effective POLISARIO forces, after 1979 the Moroccan government adopted a demographic strategy: a large-scale transfer of population into the region. Some came from the Sahara regions of Morocco, just to the north. Civil servants, skilled workers, health professionals, and teachers were sent from all over Morocco.

From the mid-1980s, the government provided economic opportunities (subsidies, tax exemptions, and higher salaries than elsewhere in Morocco) to entice migrants who would help develop the Sahara. The number of inhabitants increased from 74,000 (Spanish census, 1974) to 622, 651 today. The immigrants never really fused with the local people but they became the majority of the population in the main cities of the Western Sahara. Indigenous Sahraoui were marginalised.

Another strategy was military: building a vast defensive wall of sand (known as the ‘berm’) across the desert, three hundred miles long, seven feet high, and protected by barbed wire and radar. By 1982, this perimeter had shut POLISARIO out of the ‘useful Sahara’: Laayoune, al-Samara, and the phosphate mines. Then new walls were built, further out, excluding POLISARIO guerrillas from most of the old Spanish colony by 1985. This was an extremely expensive policy but the Saudi Arabian government underwrote the cost.

The Saharan question had become central to the survival of the Moroccan state. The King made no allowances for those who opposed the Saharan War, and the most savage repression was directed against them.