Introduction

As the Almohads were weakened, competing dynasties emerged from among their former clients and supporters across North Africa. In 1245 the Banu Marin occupied Meknes. Originally Amazigh nomads from northeastern Morocco, around Fez and Taza, they had been part of the Almohad army. By 1269, they controlled most of what would become Morocco.

They sent armies eastwards to Tripoli and northwards into what remained of al-Andalus, but they failed to hold onto it. They were essentially a Moroccan regime. They were warriors and pious Muslims, and Abd Al-Haqq, who established Marinid power, emphasised his own piety, and respect for the shari`a and scholarship. Abu Yusuf Ya’qub (1268–86), one of the greatest of the Marinids, called for jihad in al-Andalus, befriended scholars and emphasised religious orthodoxy and scholarship, entrenching Islam in the cities.

Sufis

In the countryside, mountains, and deserts, Sufi religious brotherhoods (tariqas) grew rapidly stronger. Many of their leaders (called sharifs) claimed blood descent from the Prophet Muhammad and, intellectually, from the great Sufi teacher Abd al-Salam ibn Mashish (who died around 1227), whose tomb at Jabal Alam, in the Jebala, was one of the holiest pilgrimage sites. Because the tariqas were so powerful, the Marinids generally tried to incorporate the sharifs and Sufis by marrying into their families.

The Marinids at their height

The Marinids were rich. They made their capital at Fez, rather than Marrakesh, because they encouraged trade: the gold routes shifted eastwards, Fassi leatherwork and cloth were famous and they built the Suq al-attarin (spice market). They also founded what was virtually a new city beside the old one in Fez, to house their bureaucracy and soldiers. It was heavily fortified, with thick crenellated walls and a few strong gates closed securely at night. They used the same pattern at Salé-Chella, their fortified necropolis just outside Rabat.

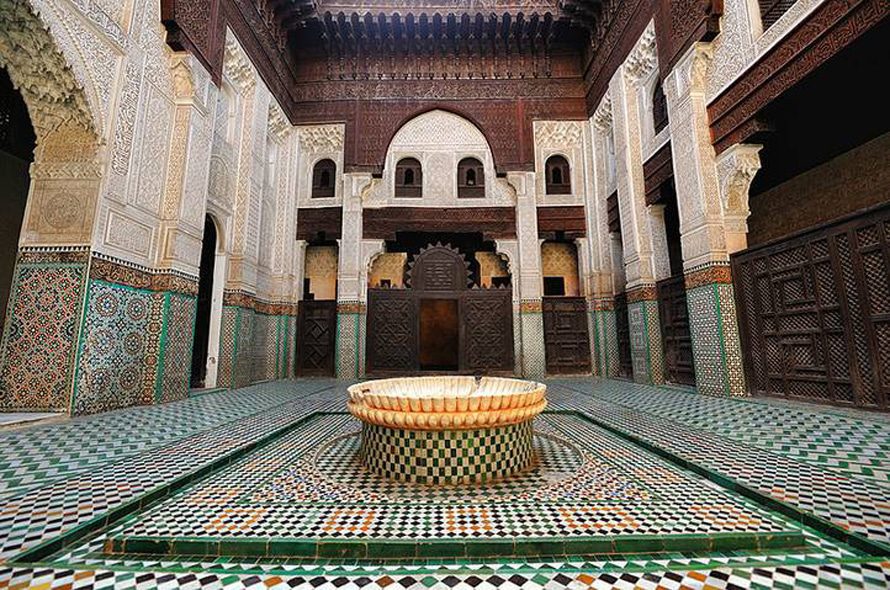

Their most impressive religious buildings were madrasas such as those built by Sultan Abu Inan Faris (1348-1358) in Meknes and Fez. Madrasas, which originated in Saladin’s Egypt, were residential colleges where students, supported by charity, lived and studied the great Islamic texts.

Decline of the Marinids

The reign of Abu Inan Faris was the zenith of the Marinid dynasty. Nevertheless, the economy faltered, and political power began slipping away. Abu Inan’s wazir (first minister) strangled his master and was then killed himself, setting off forty years of violent coups in which the wazirs and tribal groups from the mountains and deserts participated.

The outside threat grew too as the Christians in Iberia grew stronger. The Castilians raided the coasts, and the Portuguese occupied Ceuta, at the mouth of the Straits in 1415, and then other enclaves along the Atlantic coast: Ksar es-Seghir (al-Qasr al-Saghir) (1458), Asila, and Tangier (1471). The Marinid dynasty began to break up.

European invasions

The Banu Wattas, an Amazigh tribe, monopolised the wazirate and, in 1472, one of them declared himself sultan. After the fall of Granada (1492), Muslim refugees fled to Morocco. Some, hoping to continue the fight, settled in Salé. In the far south, sharifs and leaders of Sufi tariqas led the opposition to the Portuguese. The Spanish took Melilla in the far north-east in 1497, Peñon de Alhucemas and two nearby islets in 1559, and Peñon de Vélez in the west in 1564, while the Portuguese took yet more outposts on the Atlantic: Agadir (1505), Safi (1507), Azemmour (1513), and Mazagan (al-Jedida) (1515).

Loss of al-Andalus

The end of the Christian Reconquista in Iberia brought an invasion of another kind: a wave of refugees from the Iberian peninsula who sought refuge in Morocco and settled in the coastal cities in the north. Not all were Muslim – there were at least 10,000 Jews. The loss of Iberia and the Christian invasion of the coast led to a wave of jihadi feeling across Morocco, particularly in the south, near the main Portuguese enclaves. The sharifs and the tariqas were led by an alliance that laid the foundation for a new dynasty.