The unfolding of the Arab-Israeli-Palestinian conflict from the 1948-1949 war to UN resolution 242.

The War of 1948-49

The Haganah

At that time the Haganah, the largest Jewish underground military organization, consisted of some 35,000 armed men and women. There were also several thousand fighters belonging to other groups that had been operating in the shadows. This Jewish ‘army’ was only lightly armed and barely trained, but was shored up by men who had previously fought with the British army. They lacked heavy weapons and the air force had an inventory of only nine obsolete planes. This hiatus was largely filled by a deal with Czechoslovakia that provided for tens of thousands of light weapons and even two dozen Avia S-199 fighter aircraft – a Czech version of the wartime German Messerschmitt Me-109.

The Palestinians and Arabs

The opposing Arab and Palestinian forces consisted of loosely organized militia in Palestine itself, with an estimated strength of some 10,000 men, backed by regular armies of the neighbouring states of Syria, Egypt and Jordan. These had several tens of thousands of soldiers equipped with heavy weapons such as artillery and tanks – mostly pre-World War II models. The British forces in the Middle East had also handed over considerable numbers of fighter aircraft such as Spitfires and Hurricanes and transport planes. Sizable contingencies from Libya, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Yemen would play a role in the hostilities that followed.

14 May 1948

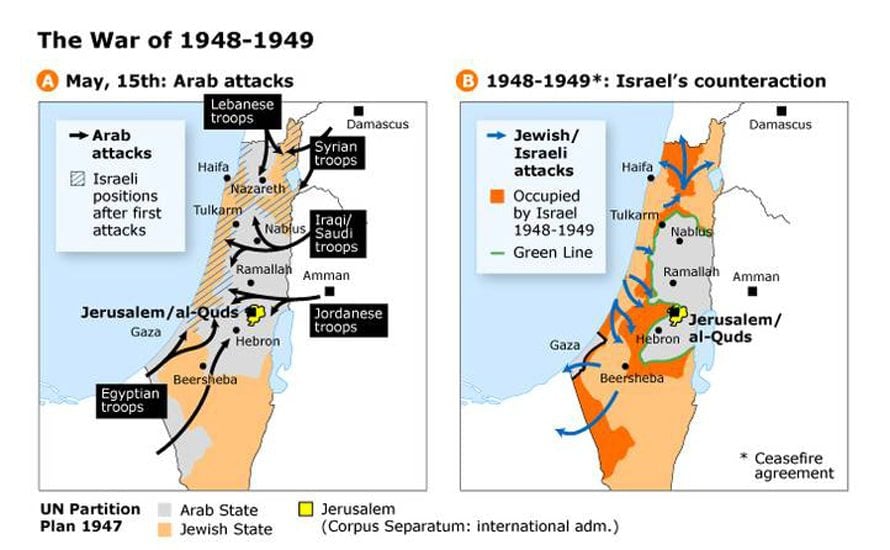

When on 14 May 1948 Israel declared its independence the regular Arab armies moved in. The day before the Arab League had already decided to send regular troops to the conflict zone that would officially be handed over by the British authorities to end the Mandate. The UN denounced the intention stated by the Arab League to protect the lives of civilians in the absence of any legal authorities.

The Arab offensive was not well coordinated, mostly because the national Arab commands did not cooperate. The attacks were blunted, stopped and repelled by prepared positions of the Jewish forces in kibbutzim and towns. However, especially in and around Jerusalem, fighting between Israeli forces and the Arab Legion, led by former British general John Glubb (Pasha), raged fiercely.

Gradually, within weeks, the first outnumbered – at least on paper – Israeli forces grew in quantity and quality and gained the upper hand. The net result was that after the fighting had died down, Israeli forces held more land than before the Arab offensive. The United Nations declared a ceasefire on 29 May 1948 and presented a new partition plan that both sides rejected.

At the beginning of July 1948 hostilities broke out again on the southern front. This time Israeli offensives led to consolidation of earlier gains and to new gains on the northern, central and southern fronts. There was also a large exodus of Palestinians fleeing the conflict zones, evicted by Jewish forces or told by their leaders to leave. Again, in September 1948 a new proposal of the UN that would settle territorial matters and compensation for refugees was rejected by both sides.

In October 1948, Israeli armed forces clashed again with the Egyptian army and succeeded in driving a wedge between the Palestinian forces and the Egyptians. At the beginning of 1949, the Israeli borders were defined by armistices negotiated separately with its neighbouring countries.

Armistice Agreements of 1949

In those years, the UN still played a central role in negotiations between Israel and the Arab states. In the early part of 1949, efforts focused in the first place on bringing about a permanent ceasefire between the warring parties. Armistice agreements, concerning armistice lines, exchange of prisoners of war and so forth, were signed between Israel and Egypt (24 February 1949), Israel and Lebanon (23 March), Israel and Jordan (3 April), and finally between Israel and Syria (20 July).

The agreements defined Israeli borders, which now encompassed 78 percent of the territory of the former Mandate of Palestine, 22 percent more than what the UN’s Partition Plan had initially established. In addition, Transjordan (from then on called Jordan) retained the West Bank of the Jordan River and the eastern part of Jerusalem, while Egypt took control of the small strip of land around the city of Gaza on the Mediterranean coast.

Furthermore, on the basis of the UNGA Resolution 194 of 11 December 1948, a Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) was set up, which consisted of the Arab states of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon on one side, Israel on the other side, plus France, Turkey, and the United States. A document the commission produced, the Lausanne Protocol (12 May 1949), showed fundamental disagreement between Israel and the Arab states: Israel preferred to deal on a bilateral basis with the Arab states (to counter their combined weight) and disputed the newly created borders (Israel still had its eye on the Gaza Strip that was now under the control of Egypt, and wanted some form of shared control in the West Bank, which had been conquered by Jordan).

The Arab states on the other hand focused on a multilateral approach and on the return of the Palestinian refugees who were hosted by them. Within a few years it became clear that the UNCCP would not succeed in its mission. Formally it still exists but now dormant, without budget or staff.

Israel Becomes UN Member

On the basis of the armistice agreements and its participation in the UNCCP, Israel was – after first being rejected in December – admitted as a member of the UN in May 1949 under the condition that it would accept UNGA Resolution 194 (UNGA Resolution 273 of May 11, 1949). Under UN pressure it declared that it ‘unreservedly accepts the obligations of the United Nations Charter and undertakes to honour them from the day when it becomes a Member of the United Nations’.

After the armistice agreements of 1949, the armistice lines with Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria became the borders of the State of Israel. Israel’s territory included land conquered in the war of 1948-1949. The special status of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, as mentioned in the UN Partition Plan, seemed to be absent from the agenda (although on December 9, 1949 in Resolution 303, the General Assembly would again stress the importance of an international regime for the Jerusalem area and the protection of the Holy Places). By failing to implement the above mentioned UNGA Resolution 194 of December 1948 concerning the right of the Palestinian refugees to return to their homeland and to receive compensation, Israel did not honour the obligations it had accepted on upon its admission to the UN.

On 12 August 1949, the Fourth Geneva Convention was adopted, which dealt with the protection of civilians in times of war and occupation. This document would turn out to be – theoretically at least – a very important judicial tool of international law for understanding the rights and obligations of all parties involved in this conflict.

Fatah and the PLO

In the next decade and a half, the Egiptian president Abd al-Nasser Nasser was the leader of a powerful Arab nationalist movement. In order to control the rise, in the same period, of a Palestinian nationalist movement (Fatah was created in January 1959, with Yasser Arafat as its chairman), the League of Arab States encouraged the formation on June 2, 1964 of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The PLO was an umbrella organization for Palestinian groupings. The League put their own man, Ahmad al-Shukeiri, a Palestinian diplomat, in charge.

The PLO Charter of 1964 (Palestine National Charter 1964) speaks of the liberation of Palestine through armed struggle, and says among other things that Palestine, ‘with the borders at the time of the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit’ (Article 2).

‘The partitioning of Palestine, which took place in 1947, and the establishment of Israel are illegal and null and void, regardless of the passage of time, because they were contrary to the will of the Palestinian people and their natural right to their homeland, and were in violation of the basic principles embodied in the Charter of the United Nations, foremost among which is the right to self-determination’ (Article 17).

‘The Palestinian people believe in peaceful co-existence on the basis of legal existence, for there can be no co-existence with aggression, nor can there be peace with occupation and colonialism’ (Article 22).

History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our coverage of the history of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Fanack’s historical record meticulously chronicles the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in a chronological sequence, encompassing its origins, crises, wars, peace negotiations, and beyond. It is our most exhaustive historical archive.