Costs of Israeli Occupation - The occupation of the Palestinian territories does not make sense economically... turning out to be a bottomless pit...

Introduction

The Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories does not make sense economically. The occupied land is turning out to be a bottomless pit for Israel financially. Although often a neglected issue, it is the rising economic cost of the occupation that will eventually drag Israel down if it does not alter its course. Not only does the occupation lay a heavy burden on Israel, it is also draining finances and goodwill from its traditional supporters, the United States and the European Union. In fact, it is this outside support that allows Israel to continue the occupation. Only recently, a handful of Israeli economists started to stress this point.

Costs of Occupation

The occupation in 1967 of Palestinian territories (hereafter Palestine) does not make sense economically. The occupied Palestinian lands are turning out to be a bottomless pit for Israel. Although often a neglected issue, it is the rising economic cost of the occupation that could eventually drag Israel down if it does not alter its course. This argument, one of the conclusions of a conference organized by the Israeli Alternative Information Center (AIC) in October 2009 in Bethlehem, is of critical importance for understanding the consequences of the continuation of existing policies.

Not only is the occupation a heavy burden on Israel, it is also draining finances and goodwill from its traditional supporters, the United States and the European Union. In fact, it is this external support that allows Israel to continue and expand the occupation of Palestinian land. Without international financial support, both Israel and the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) would have gone bankrupt long ago. However, even with continued backing, the occupation is such an expensive project that it threatens to drain the Israeli economy and social services.

Apart from legal and moral reasons, there are urgent financial considerations for Israel to abandon its policy of occupation. The occupation of Palestinian land has already deprived the Israeli economy of investment opportunities and degraded the social welfare of its citizens. The fact that the occupation is economically unsustainable in the long run hardly receives any attention. Only recently did a handful of Israeli economists start to stress this point. Today, Shir Hever from the Alternative Information Center in Jerusalem and Shlomo Swirski from the Adva Center are the most vocal in pointing out the financial burden of the occupation. Activist groups such as Peace Now have embraced the argument.

Hiding the Costs

A major problem when calculating the cost of the occupation is that it is impossible to separate the cost of the settlements from the cost of the occupation itself. The military outposts and bases created to defend the settlements carry a hefty price tag. The engine of expenditure is a vicious circle. Where the Israeli army exercises more control, lands are confiscated to build more settlements. Thus, settlement expenses lead to military expenses to provide security for the settlers, and military expenses – for increased protection – in turn enable the establishment of more settlements and so on.

The total cost of the settlements is not made public. The Israeli government is systematically concealing related data under the pretext of national security. Ironically, even government ministers cannot access the actual figures of the cost of the occupation. Israel secretly allocates millions of dollars every year to the settlements through the Ministry of Domestic Affairs, but in order to hide the extent of incentives that the government provides to potential settlers, the subsidies are distributed over countless special budgets, one-time grants and ad hoc funds to create a financial maze without transparency.

This clandestine manner of making fund transfers is used for two reasons. One is to avoid public outrage at the preferential treatment that settlers enjoy. The second is that the special subsidies given to the settlements encourage people to move to the settlements and thus violate the Fourth Geneva Convention that forbids the transfer of a civilian population to an occupied territory.

A 100 Billion Dollar Bill

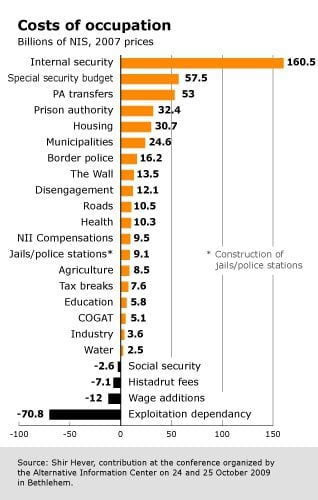

Despite the difficulties, financial expert Shir Hever estimated that the total net cost of the occupation for Israel added up to at least USD 100 billion during the timeframe 1970-2008. Annually, this equals USD 6.8 billion or 8.7 percent of Israel’s 2008 budget. It is important to note that other economists have come up with even higher estimations, ranging from 1 to 2 percent of the Gross Domestic Product annually since 1973, as resources were diverted from the economy to the occupation.

Security costs (USD 81 billion) are nearly triple the amount spent on settler subsidies (USD 27 billion) according to Hever’s calculation. This implies that the main reason for the high cost of the occupation is the Palestinian resistance. Meanwhile there is no reason to believe the Palestinians will cease their resistance. Thus the occupation will continue to be an increasing burden.

Although the list of the various costs is not exhaustive, Hever argues they provide a rough estimate of the overall burden that the occupation poses to the Israeli economy. The total figures include the extrapolation for the entire period 1970-2008, and include adjustments for price changes and interest. The growth of the settlements‘ population is also taken into account. These costs are only those paid for by the Israeli government, and exclude individual expenses on security needs, private losses due to investments in occupied lands and donations to the settlements.

Moreover, the costs have been calculated by subtracting income from expenses resulting from the occupation. Income generated for Israel from the occupation includes payments collected from Palestinians who work in Israel (such as social security), fees for the federation of labour unions in Israel, Histadrut (although they do not receive protection or assistance), and various wage additions such as a security tax to pay for the costs of monitoring Palestinians in the workplace. Income was also generated through the exploitation of Palestinian cheap labour, the captive market in the occupied territories and the usage of water and land resources. Adding these components, Hever arrived at a total income generated for Israel of roughly USD 10 billion from 1970 to 2008. It should be noted that this does not include the benefits to the Israeli economy from international aid.

It is important to add interest to both income and expenses. If there had been no occupation the Israeli government could have invested its funds in other ways and developed the Israeli economy instead. Israel could have improved its infrastructure, education and healthcare or utilized the money for debt relief. For a full picture, interest must be applied to the total cost over the time span ranging from 1970 to 2008, using the interest rates of the Bank of Israel for loans and deposits, adjusted for inflation.

The government spends an average of USD 10,500 on the average Israeli citizen, but more than double that amount – USD 24,000 – on the average settler. If this trend continues, by 2038 half of the Israeli budget or more will be spent on maintaining the occupation and occupiers of Palestine. No developed country can sustain such a burden.

Settler Subsidies

The settlements have created an enormous barrier to achieving a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. According to international law the settlements in Palestine are illegal, and therefore investments in them are also illegal. Nevertheless, in order to colonize the lands, Israel has pursued a policy of extensive subsidies to encourage Israeli citizens to live in the settlements in Palestine.

Almost 70 percent of the settlements are classified as ‘Priority A’ areas for which the Israeli government provides a subsidized loan of USD 15,400 to people moving to live there. Half of this amount becomes a grant after fifteen years. Over 20 percent of the settlements are noted as ‘Priority B’ areas, entitling settlers to a slightly lower subsidized loan. Strikingly, the Housing Ministry’s list of preferred area communities is not publicly available.

To illustrate how settlers receive incentives to move to Palestinian lands one needs only to look at the subsidies granted for agricultural investment projects in the settlements through the World Zionist Organization (WZO), which is funded heavily by the Israeli government. It is estimated by Swirski that between 2000 and 2002 alone, USD 110 million was spent by the WZO on agricultural projects in the settlements. In addition, the government finances the establishment of industrial zones in Palestine for the benefit of the settlers. According to an estimate by the economist and former official in Israel’s Finance Ministry Dror Tsaban, state subsidies of up to USD 66.2 million were provided for this purpose between 1997 and 2001. The government also provides subsidies for housing in the settlements. The distribution of loans and grants to settlers to buy real estate reached USD 1.12 billion between 1990 and 1999, says Swirski.

Settlers who have a permanent address in a settlement receive a discount in income tax. The Haaretz newspaper calculated that settlers received discounts in income tax worth a total of USD 1.13 billion from 1967 until 2003. Other estimates double that amount. Another example of how the government provides incentives to Jews to move to Palestine is that schools in the settlements receive more state funding than average schools inside Israel. Incentives to teachers, transportation for children and fewer pupils per classroom all contribute to the excess expenditure on education in the settlements. According to Relly Saar, a research journalist at the worker’s rights organization Kav LaOved in Israel, the extra funds amounted to USD 27 million in 2003 alone.

Disproportionate

In addition, settlers benefit from disproportionate spending on health care. Every 50-100 residents in isolated settlements have a clinic at their disposal, which is far beyond the ratio of clinics per capita inside Israel. Medical staff receive extra benefits for operating in the settlements, and this is accompanied by extra costs for special security measures that are considered necessary. According to Haaretz the extra health care costs in the settlements from 1967 until 2002 were as much as USD 8.7 billion.

In general, settlement municipalities have received far more funding than municipalities within the Green Line. Swirski estimates that a total of USD 890 million was provided in the 1990s as extra funding to the municipalities of the settlements. Some of these funds were even used by the settlers to finance demonstrations and campaigns against evacuation.

The rate and the cost of road construction within and to the settlements in Palestine also far exceed the rate and cost of construction inside Israel. Access to isolated settlements is made possible through a special network of bypass roads which may be used by the settlers only. Between 1993 and 2002 at least USD 450 million was spent for this purpose. Additional costs remain hidden because the budget for bypass roads was transferred to the Ministry of Defence in order to conceal it.

Providing fresh water to the West Bank settlements while preventing the Palestinians from using it, requires heavy government investment. It should be noted that Israeli water consumption is three times as high as Palestinian water consumption per capita. To illustrate, in the decade up to 2003, the expense on water infrastructure beyond the average costs for the Israeli population within the Green Line was USD 158 million, according to Haaretz.

Security Costs

Since 1967, in order to secure Israel‘s control over Palestine and to safeguard Israeli citizens from violent Palestinian resistance, Israeli authorities have pursued spatial control through surveillance, patrols, fences, barriers, checkpoints and permits. This system of spatial control has become the largest component of Israeli expenditure in Palestine. Much effort has been spent on keeping the Israeli and Palestinian populations separated – not only to prevent Palestinians from entering Israel, but also to prevent Israelis from entering Palestinian communities and interacting with Palestinians.

To illustrate the security costs, economic expert Shir Hever from the Alternative Information Center has made an estimation for a few specific items. Since 1989, in addition to the regular defence budget, part of which covers actions in Palestine, special budgets have been added for military actions in Palestine. These special additions have exceeded USD 15.2 billion. Furthermore, the Unit of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) has been operative since 1994. This maintains a budget for coordinating military activities in the OPT. For the years 1994-2008 its budget was USD 820 million.

However, the biggest security expenditure is for police and internal security in order to contain the Palestinian resistance to the occupation and to keep control over Palestine and over dissenting voices within Israel. Since 1968, the average rate of annual increase in the internal security budget has more than doubled. The Ministry of Defence not only invests in large military units for the control of the Palestinian territories but also pays for the military self-defence of the settlements. The costs include salaries and vehicles for regular security coordinators, as well as protective devices for vehicles and individuals (such as weapons and ceramic vests), fences, emergency roads, and lighting systems.

First Intifada

The First Intifada (1987-1993) altered Israel’s defence and military balance. The trend of decreasing allocations for defence in the national budget that had begun in the mid 1980s was reversed. During the Second Intifada (from 2000) the cost for military expenses went up significantly, triggered by large military expenditure.

Although Israel’s defence budget is not made public, Swirski from the Adva Center has kept track of the supplemental funds received by the Defence Ministry over the years. During the last two decades, 1988-2008, the Ministry of Defence received supplementary budgets to the amount of about USD 10.4 billion for increased activity in Palestine. The amounts served to cover the costs of the two intifadas, the cost of dealing with suicide attacks on public transportation, the cost of erecting the ‘Separation Barrier‘ (hereafter Wall) and the cost of disengagement from the Gaza Strip.

During the last decade the military cost of the occupation has no longer been covered by the budget of the Ministry of Defence but has been paid for by the Ministry of Public Security (that is the Police Ministry). Its budget has more than doubled in real terms from USD 1.3 billion in 1994 to USD 2.5 billion in 2008.

The Wall

The construction and maintenance of the Wall also falls under the category of security costs. It is patrolled by soldiers or private security companies with surveillance equipment; remote-controlled armaments are installed upon it. The Wall alone – declared illegal by the International Court of Justice in the Hague – has cost an estimated USD 3 billion, according to the Brodet Commission, which had to examine the Israeli military’s request for a large increase in the defence budget. This amount does not include the compensation that Israel has paid to Palestinians for confiscated lands. If there is no political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the budgetary costs of the conflict will continue to be a heavy burden. There continues to be a steady increase in these costs because the terrorist elements are determined to continue some sort of arms race or balance of terror.

Settlers

Another example of security costs is the expense for the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in September 2005. Under the ‘Disengagement Plan’ Israeli settlers have been evacuated from the Gaza Strip although Israel continues to exert full control over the region. According to Hever, the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip cost Israel over USD 2.4 billion, of which one third was spent on relocating military installations, and two thirds on compensation to the settlers. This suggests a grim outlook for the eventual evacuation of all settlers from the West Bank. The average settler in the Gaza Strip received more than USD 265,000 as compensation. As the less than 8,000 settlers evacuated from the Gaza Strip amounted only to about 3 percent of the total settler population, the hypothetical cost of compensating the remaining settlers in the West Bank might seem prohibitive.

If Israel decides to evacuate the illegal settlements in the West Bank, where 471,000 settlers lived in 2008, it will have to deal with their demands for compensation. If the Gaza formula is applied to them, compensation could reach USD 125 billion. This is more than 1.5 times the annual government budget. However, if the settlers are not evacuated and the cost of occupation continues to grow, Israel could end up paying even more.

Given the above calculations of the cost of the occupation, the Israeli government should make a sound economic decision to borrow enough money to finance compensation for the settlers. This is the alternative to paying endlessly for subsidies and settlement security. When it is realized that Israel will have to compensate the Palestinians eventually for the past four decades of occupation, it is clear that all of the previous estimates represent just the tip of the iceberg.

Israeli Costs

Obviously, the occupation has benefited the settlers. Secondly, it is the military officers and the military industry that enjoy the continuing need for more security measures and the constant increase in military expenditure. Private security companies have also begun to flourish in Israel. Employers can exploit Palestinian workers because the occupation prevents the Palestinians from generating income elsewhere.

Most of the costs of occupation are paid directly by the government of Israel through the state budget, which is largely funded through taxes levied on the public. Some of the costs are paid by government institutions such as the Institute for Social Security, which is one of the pillars of the Israeli system of social security, the World Zionist Organization, and the Israeli Lottery Institution.

In fact, Israeli citizens have paid dearly because the increases in the defence and security budget resulting from the occupation have resulted in cuts in the civilian parts of the budget. This has undermined the basic social arrangements in Israel, among them the social safety net, the pension system, the public school and higher education systems, the health care system and housing assistance programs. Consequently, the years between 1998 and 2007 were characterized by diminishing equality and social justice in Israel.

As economic activity contracted, tax revenues decreased. Faced with a decline in revenues and, at the same time, a demand to increase the defence budget, the government chose to cut the civilian parts of the budget. In the past two decades the ratio between defence expenditure and social service expenditure has remained stable. However, it is undeniable that increasing expenditure on military security has the effect of reducing the funds available for increasing the economic and social security of Israelis.

Second Intifada

During the period of the Second Intifada, the government increased the defence budget, in large part at the expense of transfer payments. It can be said that one of the effects of the occupation was the erosion of egalitarian forces in Israel and the deepening of social gaps.

Illustrative of such indirect effects are the large budget cuts made in the wake of the Second Intifada, which were detrimental to education budgets. Within the six years between 2001 and 2006, the allocation of teaching hours declined by 15 percent per pupil. In the coming decade, the defence budget will increase each year by a figure that is similar to the annual budget for higher education. The same trend is apparent in healthcare. The average financial burden for households more than doubled in the past decade, while the defence budget expanded.

Another indirect consequence of the occupation is political. At least since the 1980s, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has influenced the degree of stability of coalition governments. Political instability is demonstrated by the fact that in the 1990s Israel had five prime ministers. The political leadership is occupied primarily with the ongoing conflict and has difficulty finding time for the development of long-term policies in other areas.

In addition, due to the prolonged occupation, Israel has uncomfortable relations with other sizeable parts of the international community. Israel is still disconnected from many nations in the Middle East, Africa and South East Asia, and its status in international public opinion has decreased significantly over the years. Public opinion surveys point out that Israel’s image among the nations of the world is negative. Various circles in the West, mainly intellectual groups, have tried repeatedly to impose a boycott on Israeli products and even on Israeli universities and Israeli scholars. This prolonged diplomatic isolation reinforces Israel’s dependence on the support of the United States and, in fact, on becoming its protégé.

Palestinian Costs

Naturally it is the Palestinian population which pays the highest price for the occupation of its land. The growing divergence between the wealth of the average Israeli and Palestinian citizen is telling. Over the past three decades, Israeli income per capita has increased from being seven times higher than that of Palestine to being fourteen times higher. The net result of four decades of occupation are expanded Jewish settlements and controls, combined with diminishing Palestinian economic policy space, reduced physical territory, and reduced access to natural and economic resources.

In addition to their suffering and material losses, the Palestinians are forced to pay taxes to Israel, while these funds are used against them to build forts, bypass roads, roadblocks and the Wall, and to create an infrastructure for extracting their resources to the benefit of Israelis. Moreover, the profits generated by Israeli companies through the exploitation of the captive Palestinian market, and the different forms of income that Israel enjoys at the Palestinians’ expense, have helped finance the occupation.

The Israeli closure of Palestinian land has made it impossible for the Palestinians to build up a viable economy. Strict control of borders between Israel and Palestine has blocked the latter’s access to international markets. Closure between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, closure of the borders of the West Bank with Jordan and the Gaza Strip’s border with Egypt, and internal closures within the West Bank and the Gaza Strip restrict movement and trade within and between these areas.

The Wall

The Wall has an enormously destructive impact on the economy of the West Bank. Agricultural development on the West Bank was already restricted by the loss after 1967 of some 40 percent of land to settlements and related infrastructure. However, during the construction of the Wall some of the most fertile land was confiscated from Palestinian owners. Access to almost 15 percent of the West Bank’s agricultural land will be lost when the Wall is finally completed. The Wall has eroded the agricultural sector’s already limited natural resource base. Closure, checkpoints and the Wall have an impact on the Palestinian economy through multiple channels, resulting in a decreased volume of production. Needless to say, the loss of jobs for Palestinians in Israel due to the closures, hampers growth by reducing demand inside Palestine.

Deterioration of productive capacity

The productive capacity of the Palestinian economy has been subjected to extensive degradation as physical infrastructure and private and public property has been destroyed. Agricultural land, trees, factories, machines, buildings and other productive assets have been hit. Closures have compounded the loss by forcing producers to overuse the remaining capital stock to supply the local market. The deterioration of physical capital and productive assets will continue to be felt in the long term. This in turn limits the ability of the PNA to raise enough tax revenues to finance social transfers and public investment.

The near impossibility for the Gaza Strip to export agricultural produce is another case in point. Due to closures, carnation farmers exported only one-fifth of the 45 million flowers they produced in 2007. The remainder was used as animal feed. As a result they lost about USD 6.5 million. In the same season, strawberry exporters lost USD 7 million because of Israel’s closure policy.

The cumulative economic cost of six years of tight closure policy from 2000 to 2005 is estimated by UNCTAD to be around USD 8.4 billion. To put this in perspective, this loss is twice the size of the GDP of Palestine in 1999. More detrimental are physical capital losses. The Palestinian economy has lost, and not replaced, at least one-third of its pre-2000 physical capital.

Due to the systematic constraints imposed by the occupation policy, unemployment increased by more than 10 percent between 1999 and 2008 to reach 32 percent. Poverty continued to widen and deepen, with 57 percent of households in Palestine living in poverty in 2007, compared to 20 percent in 1998. The trade deficit as a ratio of GDP reached an unprecedented 79 percent. The trade deficit with Israel alone was equivalent to more than 140 percent of total international donor support to the PNA in 2008 and accounted for more than 70 percent of the overall trade deficit, according to a recent UNCTAD report.

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip has been disproportionately affected by the occupation policy due to the tight Israeli blockade since 2007. The Gaza Strip, where 40 percent of Palestine’s population lives, has seen widespread destruction of infrastructure, productive capacity and livelihoods. 30 percent of the arable land has been rendered inaccessible to Palestinian farmers. Fishing is allowed only within a narrow distance from the coast, resulting in resource depletion and declining returns. To make matters worse, the Israeli military campaign of December 2008 caused massive destruction. Material losses caused by Operation Cast Lead are estimated to be around USD 4 billion, almost three times the size of the economy of the Gaza Strip.

Nine years of intensified closures have seriously weakened the Palestinian export sector and many of the firms driven out of business are unlikely to come back if and when relative normalcy returns. Palestinian exports now are below the level of 1999.

The ultimate impact of the occupation and closure policy is the systematic erosion of the Palestinian productive base, particularly in the Gaza Strip. Palestinian people have been deprived of their ability to produce and feed themselves. They have been turned into poor consumers of essential goods imported mainly from Israel and financed by donors. Only foreign aid has prevented the Palestinian economy from complete collapse in the last few years.

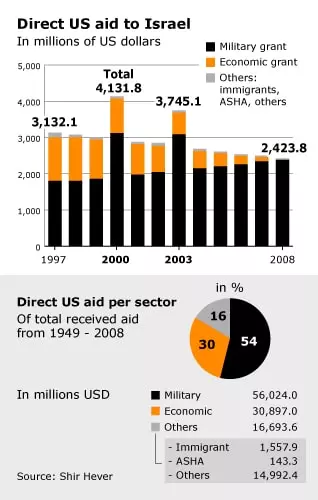

US Aid

Taxpaying citizens of the United States indirectly pick up a large part of the bill for the occupation of Palestinian territories. Israel has been the largest cumulative recipient of American foreign assistance since World War II, having received USD 113.9 billion over the period 1949 to 2008. Washington allocated about USD 1.8 billion annually to Israel in military aid after 1973 and nearly USD 3 billion in grants annually after 1985. This amounts to USD 500 per Israeli citizen. These funds, when calculated with interest, definitely surpass the security costs of the occupation. According to William Bowles of the American website Information Clearing House, although Israel’s economy should be on the brink of collapse, it is held together artificially, solely because the American aid is directly funding the occupation of Palestine.

Strikingly, all American foreign assistance earmarked for Israel is delivered in the first month of the fiscal year, while other recipients receive their aid in instalments. Receiving all of its economic and military aid directly in cash up front, with no accounting required of how the funds are used, allows Israel to gain large sums of interest on the as yet unspent money. Included in the total amount of aid are, for example, the grants for American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA) and US-Israeli cooperative programs in agriculture, science and hi-tech industries, amounting to USD 27 million over the period 2000-2005.

The United States also provides assistance in the resettlement of humanitarian migrants to Israel. This is designed to promote their integration into Israeli society, and it includes transportation to Israel, Hebrew language instruction, transitional housing, education and vocational training. Annual amounts have varied from a low of USD 12 million to a high of USD 80 million, based on the number of Jews leaving the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia for Israel. For 2008, an amount of USD 40 million was appropriated.

Since 1972, the United States has also extended loan guarantees to Israel. These loans have not yet cost the United States any money because Israel has never defaulted. They are listed on the Treasury Department’s books as contingent liabilities, which would be liabilities to the United States should Israel be unable to pay its debt. These loan guarantees are of substantial benefit to Israel because they enable Israel to borrow commercially at lower interest rates.

Estimates

A conservative estimate of total direct American aid to Israel has been made by Shirl McArthur, a former US foreign service officer and consultant in Washington. To the amount mentioned in the table above, USD 10.2 billion must be added, consisting of unidentified Department of Defence items, interest earnings for Israel which the US itself loses out on, and other grants, adding up to USD 113.9 billion over the period 1949 to 2008.

Israel and the United States have agreed to gradually phase out economic grant aid. Therefore, as of 2008 Israel is no longer a large-scale recipient of grant Economic Support Funds (ESF). To compensate for the decrease in economic aid the Bush Administration increased American military assistance to Israel by USD 6 billion for the next decade. In 2009, Israel received USD 2.6 billion in so-called Foreign Military Financing (FMF). This amount will increase annually, reaching USD 3.2 billion a year by 2018. Israel uses almost 75 percent of these funds to purchase American defence equipment. The remainder could be spent on procurement from Israeli defence companies. Due to American aid, Israel’s armed forces have been transformed into one of the most technologically sophisticated militaries in the world. The irony is that tens of billions of American tax dollars and transfers of American military technology have helped create and nurture Israel’s weapons industry, in effect subsidizing a foreign competitor. Israeli companies compete globally with top-tier arms producers, including the United States, reaping about USD 2 billion of a USD 27 billion yearly worldwide market.

In theory, Israeli dependency on American aid increases American diplomatic leverage over Israel to influence its behaviour and policies towards the Palestinians and others. However, there have been few cases when the United States has acted to restrict aid or rebuke Israel for improper use of US supplied military equipment. When Israel was thought to have used American supplied cluster munitions to counter Hezbollah rocket attacks during the July-August 2006 War in Lebanon, the United States conducted an investigation and demanded an explanation. Israel answered that the use of this weaponry was legal and announced a little later that it would begin purchasing Israeli-made cluster bombs instead.

The USD 3 billion annual aid package from the American government is in fact just the tip of the iceberg. There are many billions of dollars more in hidden costs and economic losses lurking beneath the surface. Since World War II, conflicts in the Middle East have been very costly to the United States, as well as to the rest of the world. Research conducted in 2002 by Thomas R. Stauffer, a Washington-based energy analyst and economist, concluded that US support for Israel had cost American taxpayers nearly USD 3 trillion (USD 3 thousand billion) dollars. The largest cost for the Americans is associated with the oil-supply crises and the rises in oil prices that accompanied the Israeli-Arab wars and the construction of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to insulate Israel and the United States against the wielding of a future Arab ‘oil weapon’. If Israel’s oil supply is affected, Israel in effect gets the first call on any oil available to the United States.

Crumbs for the Palestinians

Critics of American aid policy argue that it exacerbates tensions in the region. Many Arab commentators insist that American assistance to Israel indirectly causes suffering to Palestinians by supporting Israeli arms purchases. Compared to Israel, the financial support for Palestinians is a drop in the ocean. Since the death of Yasser Arafat in November 2004, American assistance to the Palestinians has been averaging about USD 360 million a year. Most US aid to the Palestinians goes through the Economic Support Fund (ESF) to US-based non-governmental organizations operating in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Funds are provided for humanitarian assistance, economic development, democratic reform, improving water access and other infrastructure, health care, education, and vocational training.

Over the past three years, American aid to the Palestinians has fluctuated sharply, largely due to the changing role of Hamas within the PNA. Hamas is designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) by the US State Department. After the 2006 Hamas victory in the Palestinian Legislative Council elections, American assistance to the Palestinians was restructured and reduced. Washington halted direct foreign aid to the PNA but continued providing humanitarian and project assistance to the Palestinian people through international and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). After the forcible takeover by Hamas of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, the United States boosted aid levels to bolster the PNA in the West Bank and assist President Mahmoud Abbas.

However, if the PNA in Ramallah is unable to achieve popular legitimacy and control in the West Bank, the United States might refrain from providing resources and training. This is due to concerns that its aid could be used against Israel or Palestinian civilians, either by falling into the hands of Hamas or otherwise. Paradoxically, instability in the Palestinian territories is both a major reason for the increase in US assistance over the past few years, but at the same time a possible reason for reducing aid levels.

In March 2009, at the international donors’ conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, the Obama Administration allocated USD 960 million in bilateral assistance for the Palestinians to address both post-conflict humanitarian needs in the Gaza Strip (USD 330 million) and reform and development priorities in the West Bank (USD 630 million). In June 2009, this amount was boosted by another USD 800 million. These amounts include direct budgetary assistance to the PNA in the form of training, non-lethal equipment, facilities, and strategic planning for PNA civil security forces. The United States is the largest single-state donor to the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which provides food, shelter, medical care, and education for many of the original refugees from the 1948-1949 Arab-Israeli War and their families. This group of recipients has grown to approximately 4.6 million Palestinians in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. American contributions to UNRWA – separate from US bilateral aid to the West Bank and Gaza – over the period 1950-2009 have amounted to nearly USD 3.5 billion.

In 2009, the United States contributed USD 98.5 million to UNRWA. Some of these funds have gone toward emergency humanitarian needs in the Gaza Strip created by the 2008-2009 Israel-Hamas conflict. All the funds are provided under the conditions of the Quartet, comprised of the United States, the European Union, the Russian Federation and the United Nations. The conditions are: (1) recognition of Israel’s right to exist, (2) renunciation of violence, and (3) commitment and adherence to to all agreements reached between Israel and the PLO/PNA. This means that either Hamas or its control over the Gaza Strip would have to change before the US dedicated substantial resources toward the reconstruction of buildings and infrastructure in the Gaza Strip. If a Palestinian unity government is established including Hamas, but Hamas does not change its stance toward Israel, this could lead to a full or partial cut-off of US aid.

European Aid

Direct financial and military support from Europe to Israel is very limited compared to American aid. Within the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), established in 2007, Israel is eligible for 14 million euros in financial assistance over the period 2007-2013.

European aid to Israel is provided mostly in the form of trade benefits. In the framework of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (PanEuroMed), bilateral agreements have been drawn up between the Community and its Member States on the one hand, and most countries of the Mediterranean basin on the other hand. Those agreements state, in particular, that products originating from the Mediterranean countries concerned, may be imported into the European Union (EU) free of customs duty.

The existing Association Agreement with Israel incorporates free trade arrangements for industrial goods, concessionary arrangements for trade in agricultural products and the prospect for greater liberalization of trade in services and farm goods. This means that Israeli products can be imported into the EU duty-free or at least with a reduced level of duty being applicable. Due to continuing settlement building and the blockade of the Gaza Strip, an upgrade of the Association Agreement was put on hold following a vote in the European Parliament.

Contrary to Israeli wishes, the benefits of the preferential system do not apply to products originating from Jewish settlements because they have been produced outside Israel’s own territory. In response to pressure from activist campaigners who have argued that settlement products violated human rights, the EU adopted a technical arrangement in 2005 whereby Israeli exporters have to provide proof of the origin of their goods. The EU drew up a list of settlements and their postcodes which it considered to be beyond Israel’s 1967 borders. One of the main problems, however, is that the system relies on correct labelling by the exporting company. EU customs authorities do not have the authority to go to Israel or Palestine to check the origin of goods.

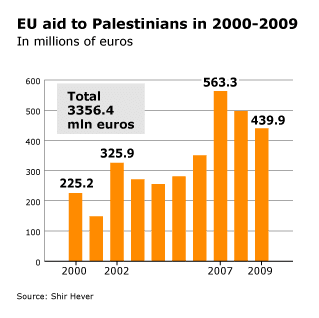

Paying for Palestinian Survival

The EU has the status of being the Palestinians’ most generous donor. EU-assistance to the Palestinians began in 1971, when the first contribution was made to the regular budget of the UNRWA. Since 1994, taking the contributions of the European Union and the EU Member States together, the EU has provided more than half a billion euros in assistance to the Palestinians. Up until the Second Intifada, the EU’s assistance was focused on development assistance. The outbreak of the uprising and the severe decline in the economic and social conditions moved the European Commission to reorient its assistance towards direct financial support to the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) budget, assisting the PA in preparing itself for statehood, reviving the economy and addressing urgent humanitarian needs.

In June 2006, the Temporary International Mechanism (TIM) was established to deliver direct assistance to the Palestinian people. The TIM was funded by the European Commission, EU Member States, and other donors to provide essential services and financial support to vulnerable Palestinians. A total of 615 million euros was collected and disbursed. Following the United States in boycotting Hamas after 2006, the EU excluded the Hamas government from access to TIM funds. Only the election of the interim government of Salam Fayyad, which excluded Hamas, convinced the European Commission to allow Palestinian access to TIM in June 2007.

Almost one quarter of the Palestinian population, more than 155,000 households, have benefited from TIM social allowances, including over 77,000 Palestinian civilian public service providers and pensioners, and 79,000 households in need. In the West Bank and the Gaza Strip TIM also helped to cover running costs and provide consumables and equipment for hospitals and schools. In addition, it contributed to the continued supply of essential public utilities, including access to electricity, water and sanitation for 1.3 million people in the Gaza Strip.

In February 2008, a new mechanism to support the PNA and the Palestinian people was applied to replace TIM. The so-called Palestino-Européen de Gestion de l’Aide Socio-Economique (PEGASE) was launched as a three-year plan, to be implemented in conjunction with the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP) running from 2008 to 2010. PEGASE is managed by the European Commission and is also open to other international donors who wish to contribute. The PNA called on donors to donate USD 5.6 billion to implement the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan. Donors agreed to pledge even more: USD 7.7 billion. The PRDP emphasizes the private sector, opening up the Palestinian economy to foreign business and relinquishing the PNA’s authority to determine economic policy in Palestine. An unprecedented USD 3.4 billion to support Prime Minister Fayyad’s plan was pledged by the participating countries at the Paris Donors’ Conference in December 2007.

Through PEGASE, the European Commission still pays the salaries and pensions of over 28,000 Gazan public service providers and pensioners, as well as the social allowances of more than 24,600 vulnerable households in the Gaza Strip. It also pays for industrial fuel for the Gaza electrical power plant. Nevertheless, international pledges of support have proved insufficient to cover the PNA’s monthly budgetary expenses. Occasionally, last-minute calls for assistance are made by Fayyad to obtain adequate funding.

The hostilities during the large-scale Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip that started late 2008 and ended in January 2009 caused an estimated USD 1.9 billion in direct material damage. At the Sharm el-Sheikh Donors’ Conference on 2 March 2009 international donors pledged almost USD 5.2 billion to support the Palestinian National Early Recovery and Reconstruction Plan for the Gaza Strip (2009-2010) as presented by the PNA. This was USD 2.4 billion more than was requested. Some USD 1.6 billion of this represented new funds destined for the Gaza Strip. The European Commission alone pledged around 440 million euros for 2009. These funds were not new funds, but came from existing budget lines. Out of the 440 million euros more than 50 percent was earmarked for the Gaza Strip. Incidentally, no claim for compensation for damage inflicted on EU-funded infrastructure or projects during the Gaza campaign was submitted either to Hamas or to the Israeli government.

Apparently, Europe has assumed the responsibility to help the Palestinians survive. Despite the growing humanitarian needs of the Palestinian population, Israel has prevented EU-aid from reaching the needy. Israel restricts imports into the Gaza Strip to a very limited number of humanitarian goods on a day-to-day and case-by-case basis, resulting in high storage fees and greatly increased transaction costs for aid agencies. So far the reaction of the EU to the continued Israeli access restrictions has been limited to words. Appeals by the European Commission, the Council of the EU, and the EU Presidency have not changed Israel’s policy.

In the meantime, Israel profits from EU-aid flowing to the Palestinians. Aid agencies often import the materials they need from Israel because it is cheaper to import goods to Palestine from Israel than from neighbouring countries. This creates a steady and lucrative business for Israeli companies. Much of the aid money thus ends up in the Israeli economy.

Conclusions

The Israeli occupation of Palestinian land continues because Israel receives sufficient financial support to perpetuate it. This was one of the conclusions of the conference, organized by the Alternative Information Center in October 2009 in Bethlehem. Although the Israeli economy is under pressure, US funds and arms continue to reach Israel and allow it to maintain its military superiority.

Israel receives more aid than Palestine in total as well as in per capita terms. In fact, Israel ranked as the fifth highest recipient of per capita aid worldwide between 1994 and 2006. In terms of total aid, Israel was the second highest aid recipient. In contrast, Palestine ranked as the 11th highest recipient of aid worldwide.

By comparing the level of aid to Palestine with the level of aid to Israel, it is evident that Israel enjoys a superior position. Most importantly, aid to the Palestinians comes mostly in the form of food and medicine, education and relief. Israel, however, receives most of its aid in the form of weaponry. Aid has failed, therefore, to narrow the gap in power between occupier and occupied.

Aid undermines the political struggle of the Palestinians. Apart from serving as a stop gap preventing a humanitarian disaster, aid also reinforces the occupation and hinders political advancement towards a solution. It normalizes the situation of the occupation and delays a permanent solution.

Palestinians receive substantial aid relative to their locally earned income. However, the aid is doing little to stave off the rapid deterioration of the Palestinian economy. The growing dependency means that the economic growth of Palestine is not catching up with the growth in aid. The result is that the dependency rate, defined as the ratio between aid and GDP, has increased from 14.42 percent in 1996 to 35.34 percent in 2006. Palestine is the fifth most dependent entity in the world.

Thus foreign aid has become the defining feature of the Palestinian economy. Nearly one million Palestinians live off their PNA monthly salaries, which are paid on time and funded by foreign donations. No less than forty thousand live directly off their salaries from externally funded NGOs, and many thousands more live on NGO projects and handouts. Thus, the livelihood of most Palestinians who have a steady income depends on political decisions external to them, and beyond their control.

Most aid agencies prefer to provide development aid rather than humanitarian relief. It is argued that economic improvements will catalyze popular support for the peace process. Yet the failure of the economy is not a technical problem but a political one, and it requires a political solution. Israeli restrictions on movement and access are the main reason for the lack of Palestinian economic growth and development.

De-Development

Therefore, donors find themselves forced to funnel development aid into emergency funds in order to prevent a humanitarian crisis. As a result, the ratio of development aid to humanitarian aid has fallen dramatically from 5:1 to 1:7 since the beginning of the Second Intifada.

The term de-development can be used to describe the economic relationship between Israel and Palestine. The deliberate, systematic weakening of an indigenous economy by a dominant power is why, after massive aid investments totalling close to USD 10 billion over the last decade, Palestinians today are living under conditions that are worse than when the Oslo Process began in 1993. Today in the Gaza Strip, at least 80 percent of the population relies on humanitarian aid and 40 percent are unemployed.

Palestinians have been transformed and reduced to a humanitarian problem. By supporting Palestinians under occupation, the international donor community enables and assists that occupation. By giving aid, donors offer a substitution for the responsibility of addressing the problems created by the occupier.

American and European citizens pay for the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land; hence their contribution has become part of the problem. International assistance was intended to build Palestinian institutions which could form the embryonic structure of the future Palestinian state, but in fact, foreign aid rapidly became a means to keep the Palestinians alive and pay for the running costs of the Palestinian National Authority and the salaries of its civil servants. International assistance has been used to compensate for Israeli restrictions on access and movement.