Introduction

The Oslo Agreements of September 1993 did not directly tackle the refugee issue, nor did they affect their status. Similarly to other ‘permanent status issues’, such as Jerusalem, settlements, security arrangements, borders, relations and cooperation with other neighbours and ‘other issues of common interest’, the refugee issue was deferred to a second stage of the bilateral Israeli-Palestinian negotiations to start during the third year of the interim period. The legal status of the refugees thus remained unchanged, except for the refugees residing in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Together with the indigenous inhabitants of these territories, they obtained new identity cards delivered by the newly created (1994) Palestinian National Authority (PNA). However, by setting out a five-year interim period, at the end of which the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be solved – including the refugee issue – the Oslo Agreements revived the debate about the political and humanitarian components of the refugee issue.

Long Term Adaptation of the Refugees

While reinforcing a ‘positively’ discriminating attitude towards the Palestinian refugees, the main host countries of the Middle East have, since the suspension of the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks in 2001, pursued a parallel policy: adapting the refugees’ long-term presence to the requirements of the socio-economic modernization agenda spurred by globalization. This policy has mainly materialized through rehabilitation projects aimed at upgrading the physical and social infrastructure of the refugee camps.

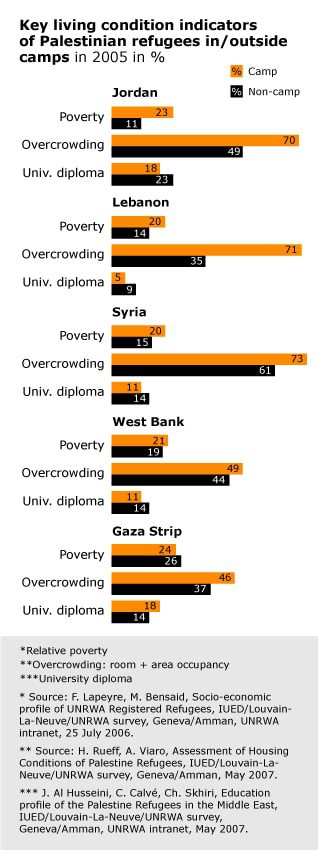

Because their temporary status (pending the implementation of the Right of return) had to be maintained, the refugee camps have remained excluded from the host countries’ municipal and national development policies. Several decades after their establishment, they have thus remained underprivileged and neglected areas. In 2005 a comparative survey was conducted by the Geneva and Louvain-la-Neuve universities on Palestinian refugees in UNRWA’s five fields of operation. This showed that, from most accounts, the refugees’ living conditions inside the camps were worse than outside them, except in the Gaza Strip. This is, for instance, the case in three key areas: (relative) poverty, housing conditions (overcrowding in the housing unit) and educational attainment. Conversely, however, camp inhabitants benefit from certain advantages, compared to the poor inhabitants of ‘informal refugee settlements’: housing is cheap – or free of charge for the camps’ original inhabitants – and the camps host the full range of UNRWA’s network of humanitarian facilities (schools, health centres and ration distribution centres), which is not the case elsewhere.

The poor state of the refugee camps may also be ascribed to the fierce resistance of the refugees to any developmental scheme that may prejudice their chances of eventual repatriation. For instance, it took UNRWA and the host authorities almost ten years (from 1951 to 1961) to convince all camp refugees to have their tents replaced by barracks and concrete shelters. It took decades to attain full access for the camps to municipal services. For instance, only half of the shelters were connected to municipal water systems in 1980 (from 10 percent in 1967) and quasi-universal access was only achieved in the period 1990-2000.

However, from the early sixties, the refugees started to restore and extend their housing units with UNRWA’s technical and financial support. The move towards the de facto normalization of the (urban) camps was facilitated by the gradual integration, since 1967, of the refugees in the local and regional Middle Eastern economy, namely the Gulf States and Israel for the refugees of the West Bank and Gaza. Increased income led to improvements in the camps’ shelters. This trend expanded quickly during the 1980s in Palestine.

By then most refugees agreed that, contrary to a well-entrenched belief since the 1950s, the improvement of living conditions should not be considered a renunciation to their claim to Return to their original homes. One should bear in mind that by the 1980s, most refugees had never been to Palestine, and the West Bankers or Gazans that had been given access to their original towns and villages after 1967, realized that those places did not correspond to their parents’ or grandparents’ narratives. However, if the notion of actual return was less pressing than in the first years of exile, most if not all refugees agreed that, pending the achievement of a just peace agreement, the camps were to be maintained as a reminder of the humanitarian and political dimensions of the refugee issue.

Rehabilitation schemes thus came to be largely accepted insofar as the camps maintained their temporary character, and UNRWA, the main stakeholder, remained the main actor in the rehabilitation process. Furthermore, as the PLO realized in the 1980s, in the context of the Israeli occupation authorities’ attempts to re-house refugees of Palestine outside the camps, improving the living conditions in the camps would be instrumental in guaranteeing their survival.

Camp development

This rehabilitation trend has remained uneven, depending on both the evolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict and its repercussions in each of the host countries. The first generation of camp rehabilitation plans fully endorsed by the United Nations targeted Palestine first within the context of the First Intifada (1987-1993). An ‘Expanded Program of Assistance’ (EPA) was launched in 1988, aimed at improving the camps’ physical infrastructure (roads, water systems, shelters, health and educational facilities). Within the Oslo process, the Peace Implementation Program (PIP) furthered the EPA on a larger scale with a view to contributing ‘to the economic and social stability of the occupied territories’ and more specifically the newly created PNA. The PLO Department of Refugee Affairs bolstered this developmental trend in 1996-1997 by establishing Services Committees in each camp in Palestine whose mandate to date is to implement, in coordination with UNRWA, developmental projects, including the rehabilitation of the road, water and electricity systems.

Since the early 2000s, similar rehabilitation endeavours have been carried out in the other host countries with the apparent support of the populations concerned. The idea that such an approach to camp development may promote permanent resettlement still prompted public debates among refugees and within their host societies. However, the idea that the camps’ temporary status needed to be improved for the sake of all still prevailed. Jordan has been the boldest of all the host countries. Since 2000, its authorities have unilaterally integrated the refugee camps into the country’s national development policies, aimed at improving living conditions in the Kingdom’s poorest areas.

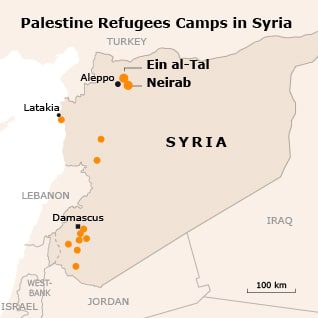

Syria: Neirab and Ein al-Tall camps

The Syrian authorities have assisted UNRWA in the implementation of large-scale water/waste-water rehabilitation in several camps of the country. Syria‘s flagship program is the dual Neirab/Ein al-Tall camps rehabilitation project (near Aleppo). Started in 2001, this project has entailed the relocation of 300 families of the overcrowded Neirab camp and a new urban planning design that is meant to secure adequate housing and public spaces for its inhabitants. The departing families were relocated in the neighbouring unofficial camp of Ein al-Tall in brand new model housing units tailored to each of the household’s basic needs. One of the more remarkable aspects of the on-going Neirab/Ein al-Tall project is the reliance on a participatory approach, whereby the Neirab camp refugees have been involved in its elaboration and implementation.

This participatory approach has also been used by UNRWA within post-emergency camp reconstruction operations. Cases in point are the reconstruction of those areas of the Jenin camp (West Bank) that were demolished by the Israeli army in April 2002 and of the Nahr al-Bared camp in Lebanon that was razed during the clashes between the fundamentalist Fatah al-Islam faction and the Lebanese army in 2007. Both reconstruction projects have induced new urban planning designs, guaranteeing suitable housing and community spaces for the camps’ inhabitants. Finally, even Lebanon has been more supportive of camp rehabilitation projects since 2005, including the PLO-controlled camps in southern Lebanon, for which access to construction materials had previously been restricted.

The Arab League officially supported these new approaches to camp development in 2002 when it called on UNRWA to coordinate, together with local authorities, projects relating to infrastructure in the refugee camps. However, this evolution should not (yet) be considered a step towards a generalized assimilation of the refugees in the host countries. First of all, the host authorities have repeatedly insisted that the rehabilitation interventions carried out in the camps were not meant to have any political connotations: they were carried out purely on humanitarian grounds. Besides, the above-mentioned rehabilitation interventions have not solved the camps’ main problem, which stems from the pressure of demographic growth combined with restrictions on camp expansion. This has led to extremely high population density and overcrowding rates (see infographic above): in Jordan for instance, population density in the camps varies from 34.000 to 103.000 persons per square kilometre, compared to fewer than 30.000 persons per square kilometre in such ‘overpopulated cities’ as Mumbai and Calcutta in India.

The ensuing health and social problems have been compounded by a lack of adequate urban planning: the original shelters expanded first horizontally, then vertically, built in an anarchic fashion by the refugees themselves. Neither UNRWA nor the host countries ever took responsibility for managing the evolution of housing in the camps. Whereas the above-mentioned physical infrastructure rehabilitation interventions have enabled the refugees to better benefit from municipal services, camps are still plagued with unsatisfactory environmental conditions in terms of ventilation, sunlight, humidity, privacy and lack of recreational areas. Such substandard conditions have been said to provoke domestic violence and to provide children with a poor study environment, encourage school dropout numbers and heighten illiteracy.

Life in the UNRWA Neirab refugee camp

All Photos are from the UNRWA Photo Archive, used by permission. Visit www.unrwa.org for more information about the UNRWA camps.

Refugee status quo

The Arab host countries’ insistence on keeping the refugee status alive is demonstrated by their stance vis-à-vis UNRWA. The Agency is still viewed, for socio-economic and political reasons, as the major stakeholder operating amongst refugees, and more especially in the camps. Even Jordan, which has initiated camp rehabilitation projects of its own in past years, has kept insisting that UNRWA expand its regular activities.

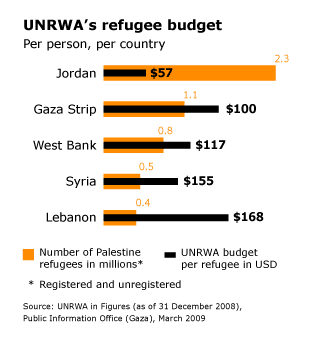

Its representatives have repeatedly complained that, while it was the largest recipient of Palestinian refugees, UNRWA’s budget in Jordan was the lowest of all: USD 57 compared to USD 100 in Syria, USD 117 in the West Bank, USD 155 in the Gaza Strip, and USD 168 in Lebanon. More to the point, in recent years the Arab countries have opposed any reform of the refugees’ internal status. In March 2005, for example, they rejected Palestinian president Abu Mazen’s suggestion that host countries confer citizenship on the Palestinian refugees, pending the achievement of a permanent status agreement.

Actually, the failure of the peace process, together with Israel’s refusal to budge on the right of return and the internal turmoil any change of the refugees’ status would create, have left the Arab countries with no other option than to preserve the status quo. To some extent, this also holds true for the PNA. Its initial intention to normalize the refugee presence in the wake of the Oslo Agreements has been thwarted by the refugees’ insistence on keeping the camps as separate administrative entities. Because of this, camp refugees, except those in some areas of the Gaza Strip, were not involved in the 2005 municipal elections.

Questioning of the Refugees’ Right of Return

Ever since 1948, the Palestinian refugee question has been a core element of the Palestinians’ and Arabs’ political conscience, pervading their political discourse around the concept of the right of return. Its significance was further heightened by the evolution of the Palestinian national movement. Following the rise to prominence of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) on the international scene in the 1960s and the ensuing recognition by the United Nations of the Palestinians as a people, the refugees’ individual Right of return was transformed into a national question within the broader framework of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination.

The UN fully endorsed that conception of the right of return in 1974, when its General Assembly reaffirmed in its resolution 3236 (XXIX) of 22 November ‘the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and [called] for their return’. Simultaneously, the PLO was eventually recognized by the Arab League and the United Nations as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and their rights, including their Right of return.

The ensuing development of the PLO into a bureaucratic pre-state entity and the growing awareness, especially after the 1973 October War, that Israel could not be entirely defeated, led to a redefinition of the concept of the liberation of Palestine as the establishment of a Palestinian state in any parts of the occupied areas evacuated by Israel. This implicitly meant a state limited to the territories of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. The implications of this strategic shift on the Right of return and its implementation were not dealt with at once. The preservation of national unity at a time when the PLO was still headed by a refugee leadership in exile required the covering up of any potentially divisive issue amongst the Palestinians.

Declaration of Independence

By reviving the Palestinian state project in Palestine, the First Intifada (1987-1993) definitely steered the PLO’s priorities towards ending the Israeli occupation and anchoring its institutions in these territories. As a result, the refugee question lost some of its prime importance in Palestinian politics. The 19th Palestinian Council’s political resolution, which included the Palestinian Declaration of Independence (November 1988), mentioned neither the Right of return, nor UNGA resolution 194 (III). Broaching the refugee issue, it just advocated ‘the settlement of the Palestine refugee issue in accordance with the pertinent United Nations resolutions’.

Furthermore, the International Conference it called for was solely based on Security Council resolutions 242 (22 November 1967) and 338 (22 October 1973), which mainly referred to the ‘necessity for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem’. The Palestinian leadership went so far as to reinterpret UNGA resolution 194 (III) in a way that departed from the ‘Right of return’ orthodoxy it had promoted so far. In late 1988, PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat officially recalled – notably before the European Parliament in Strasbourg – that resolution 194 (III) also provided for compensation in exchange for return.

Two years later, Abou Iyad, a senior PLO member, acknowledged in the Spring 1990 issue of Foreign Policy, that a complete return of the refugees was not possible, not least because Israel had systematically razed more than 400 towns and villages between 1948 and 1949. Moreover, it was not certain that large numbers of Palestinians would want to live under Israeli rule, especially if a Palestinian state existed as an alternative. He therefore urged Israel to accept the principle of the Right of return and compensation, leaving the details of such a return open for negotiation.

This new pragmatism, articulated around the idea of a difference between the principle of the Right of return (non-negotiable) and its implementation (negotiable), has gained currency amongst the PLO and other Palestinian leading personalities to become their official motto within the permanent status negotiations with Israel since the late 1990s. In the margins of the Annapolis summit (27 November 2007), Sari Nusseibeh, the dean of al-Quds University (East Jerusalem) and also the representative of the PNA in Jerusalem, stated in the Israeli media that the Palestinians would rather trade the right of return for full Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 borders.

For his part, the Palestinian PNA President, Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen), acknowledged that a massive repatriation of the refugees to Israel would destroy the country: return to Palestine would thus chiefly concern the territory of a future Palestinian state, limited to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and living in peace with Israel.

Yet, in the absence of any reciprocal conciliatory steps from Israel, which maintained its intransigent stance, denying any Right of return for the Palestinian refugees, be it in principle or in practice, the PLO’s pragmatic stance has failed to co-opt the refugees as a whole. The years that followed the launch of the Oslo process were marked by severe tension between the Palestinian leadership at the head of the PNA/PLO and the refugees, particularly in Palestine. Not that the refugees did not share the Palestine leadership’s pragmatic stances.

As several surveys have shown most refugees would not readily go back to their original homes and become Israeli citizens, were they given the choice to do so. However, the vast majority of them staunchly defend the idea that the Right of return should be recognized as such by all stakeholders, including Israel, in accordance with relevant international law regulations. Eventually, the right to choose between a return to the residence of origin and compensated resettlement (as recommended in UNGA resolution 194 (III) first belonged to the refugees themselves and was not to be circumvented for the sake of a Palestinian state. In the meantime, UNRWA had to continue to perform its humanitarian activities.

The little progress achieved by the Oslo process during its interim phase, together with the adoption by the PNA of unilateral measures aimed at ‘normalizing’ the refugees’ status in Palestine, aroused fears among refugees that the Palestinian negotiators were about to sell out their cause. This prompted them to mobilize in order to bring the Right of return to the top of the Palestinian national agenda. The fiercest mobilization campaign took place in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, where refugees had gained political clout through their participation in the 1996 general elections.

Under the auspices of several refugee advocacy institutions, a large scale mobilization campaign, including demonstrations, petitions and even institutional attempts to create an autonomous refugee representative body for the permanent status negotiations, was launched between 1995 and 2000. Not surprisingly, most refugee activists came from the refugee camps. The state envisioned by the Palestinian leadership as a Middle Eastern Singapore did not give adequate consideration to the status and the role camp refugees would play in such a state. Comparatively poorer, less educated and more conservative than average, camp refugees were seen as a burden – or even as a threat – to the Palestinian state formation process.

This idea gained popularity among the non-camp inhabitants of Palestine. The post-1993 period saw tensions erupt in the West Bank between both communities (and between the PNA apparatus and the camp refugees) over such issues as the distribution of municipal services (electricity and water) or the possession of weapons by camp dwellers. In general, camp refugees have complained that, similarly to camp refugees in the other host countries, the ‘native population’ discriminated against them socially. In the Gaza Strip, the refugees – camp and non-camp dwellers – have resented the fact that their power within society was circumscribed by their status.

The Palestinian leadership managed to re-establish its political authority over the refugees by publicly recognizing, as early as 1996, the pre-eminence of the right of return and the role the camp refugees had played within the Palestinian resistance movement. Its plans to integrate the West Bank camps within the adjoining municipalities and to take over some of UNRWA’s tasks prior to the permanent peace deal with Israel were abandoned. However, as observed above, this did not alter its conciliatory stance with regards to the right of return for the sake of the creation of a Palestinian state. Furthermore, several crucial questions remained conspicuously absent from the leadership negotiating program.

These included inter alia the absorptive capacity of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the modalities of compensation, and, perhaps more critically, the permanent status of the Palestinian refugees who would remain in the Arab states, including the nature of their links with the future Palestinian state.

The Arab Host Countries in the ‘Post-Oslo’ Era

The Oslo Agreements have had adverse effects on the refugee communities residing in the Arab host countries. Excluded from the bilateral format of the peace process talks, the latter found themselves in the unenviable position of having resettlement schemes imposed on them, regardless of the political and financial challenges such schemes would entail. At stake was not only the financial cost incurred by taking over UNRWA’s services but also the rehousing of the camp refugees.

The permanent settlement of the (former) refugees would induce a comprehensive re-definition of their legal status that would probably shift the balance of power that had so far guaranteed the status quo between the indigenous population and the refugees at municipal and national levels. This will especially be the case if they are conferred formal citizenship, as in Jordan, instead of, or in addition to a Palestinian citizenship.

These daunting challenges initially prompted the host countries to tighten their position on the refugee issue. This first entailed a reaffirmation of their commitment to the refugees’ Right of return and a reassertion of the international dimension of that issue. With this in mind, the Arab League adopted a resolution in March 2007 pressing for the active involvement of the UN in the permanent-status agreement process through heightened roles for UNRWA and the UNCCP. Simultaneously, in the late nineties, the host countries flatly rejected the Western-sponsored informal plans aimed at permanently resettling the bulk of the Palestinian refugees in their current place of residence (except in Lebanon) despite large financial packages being offered.

Even Jordan, which had signed a peace treaty in 1994 with Israel that largely focused on the need to settle the refugees, cold-shouldered the last minute attempt made by the administration of the American President Bill Clinton to salvage the Oslo process in December 2000 (the so-called Clinton parameters). Recalling that the refugees residing within its territory were fully-fledged citizens, Jordan’s prime minister emphasized Jordan’s own interests, especially when it came to the Palestinians’ Right to return and to be compensated.

This meant that Jordan had to be counted as an essential stakeholder in the Oslo process. Since 2002, most Arab countries have gathered behind the rather non-committal Arab Peace Initiative. Launched during the Arab League Summit of Beirut (28 March 2002), this initiative reiterated the call for the ‘achievement of a just solution to the Palestinian refugee problem to be agreed upon in accordance with UNGA resolution 194 within the framework of a so-called two-state solution’. The modalities of implementation of that resolution, in particular with regard to the return/compensation dilemma and the modalities of permanent resettlement, were left unaddressed.

Lebanon

Simultaneously, the main host countries have sought to strengthen the formal/informal discrimination against the refugees. In Lebanon, the authorities have resorted to various excuses – from the necessity of preserving the right of return to the need to respect the country’s socio-economic and political balance, as required by the 1989 Taif agreements – to enforce legal restrictions against the Palestinian refugees, especially in relation to access to inheritance rights and the acquisition of private property. As a result, and in line with the Lebanese authorities’ inclination, the number of Palestinian refugees actually living in Lebanon has decreased dramatically: while the number of refugees registered with UNRWA amounted to about 392,000 people in 2003, the number of them actually residing in the country was estimated at less than 200,000. However, since 2005, the Lebanese government has sought to alleviate the refugees’ hardship by allowing registered Palestine refugees born in Lebanon to work in manual and clerical jobs and to issue them previously denied work permits. They are still denied access to liberal professions though.

Jordan

In Jordan, an informal nationalistic movement fearing a gradual transformation of Jordan into an alternative Palestinian state (al-watan al-badil) surged in the mid-late 1990s. The movement publicly questioned the allegiance of the refugees to the Hashemite regime and criticized their grip on the private sector of the economy. In parliament, the politicians supporting the movement also insisted that, were a peace deal to be struck, Jordan should be compensated not only for the sums incurred by the permanent resettlement of the camp refugees, but also for all the services rendered by Jordan to the entire refugee population since 1948.

Likewise, nearly every step taken by the authorities to improve the living conditions of the (non-Jordanian) displaced ‘Gazans’, such as the issuing of residence cards in 2004, designed to facilitate daily transactions, has been criticized by the same political circles out of fear that it could pave the way for a permanent resettlement of this population and of the refugee population as a whole. That movement has subsided since the suspension of the Oslo process in 2000-2001 and the launch, as from 2002, of nationwide reform programs, such as ‘Jordan first’ (2002) or ‘We are all Jordan’ (2006), aimed at reinforcing the cohesion among the various segments of Jordanian society, whatever their origin, around the concept of a national Jordanian identity.

The problems caused by the existence of a separate Palestinian identity in Jordan and, more precisely, by the handling of a dual Palestinian refugee/Jordanian citizen status still fuel the political debate, especially in connection with the refugees’ representation in public institutions, but the tone of the debate is more subdued than it was during the heyday of the peace process in the late 1990s.

Libya

It is in Libya and Iraq, two relatively minor host countries in terms of numbers of refugees hosted, that the Palestinians’ vulnerability has best been exposed. In 1995, in the midst of an illegal worker expulsion campaign, the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi threatened to expel all 30,000 Palestinians then living in the country in order to demonstrate the futility of the Oslo Agreements and the inefficiency of the newly created PNA. Eventually, despite protests from the Arab world and the international community, 2,500 refugees, whose work contracts were terminated by the Libyan authorities, were expelled from the country and deported by sea. Most of them were stuck for several months, as no Arab country (including the PNA) was willing to take them in. Eventually, Gaddafi suspended his expulsion orders and most expelled Palestinians were allowed to return to Libya, apart from some 200 of them – including underprivileged families – who remained stranded on the Libyan-Egyptian border for a couple of years, surviving with little assistance in the makeshift Salloum camp.

It is in Libya and Iraq, two relatively minor host countries in terms of numbers of refugees hosted, that the Palestinians’ vulnerability has best been exposed. In 1995, in the midst of an illegal worker expulsion campaign, the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi threatened to expel all 30,000 Palestinians then living in the country in order to demonstrate the futility of the Oslo Agreements and the inefficiency of the newly created PNA. Eventually, despite protests from the Arab world and the international community, 2,500 refugees, whose work contracts were terminated by the Libyan authorities, were expelled from the country and deported by sea. Most of them were stuck for several months, as no Arab country (including the PNA) was willing to take them in. Eventually, Gaddafi suspended his expulsion orders and most expelled Palestinians were allowed to return to Libya, apart from some 200 of them – including underprivileged families – who remained stranded on the Libyan-Egyptian border for a couple of years, surviving with little assistance in the makeshift Salloum camp.

Iraq

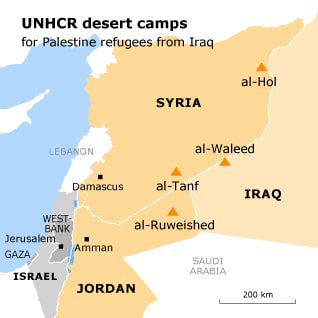

A decade later, the situation of the 30,000 Palestinian refugees residing in Iraq deteriorated quickly following the downfall of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in 2003. Accused of collusion with the latter and al-Qaeda groups, many of them suffered acts of violence from the authorities or Shia militias, including arbitrary arrest, torture, and murder. Since 2003, some 21,000 of them have fled the country. A few hundred families (about 3,000 refugees) have remained stranded in makeshift camps run by the UNHCR in the border regions with Syria (al-Tanf and al-Waleed camps) and Jordan (al-Ruweished and Karama camps). Both countries have refused to take them in, whereas they have granted the right of asylum to about 1.5 million Iraqi refugees. Expatriation to areas remote from the Middle East, like Sudan, Western Europe (Denmark, the Netherlands and Iceland), Latin America (Brazil and Chile) or New-Zealand, has been the only suitable long term solution to their humanitarian plight. In any event, their experience symbolizes the persistence, sixty years after the 1948 exodus, of the Palestinian refugees’ political and humanitarian predicament in terms of statelessness, denial of civic rights, and precariousness of living conditions. It also pinpoints the failure of the Oslo Accords and the state formation project these agreements were expected to bring about.

Concluding Remarks

The Palestinian refugee issue is twofold: at the diplomatic level, it is one of the most intricate bones of contention between Israelis and Palestinians within the permanent status peace talks. At the (internal) host country level, it has constituted a dilemma for the local authorities: how to integrate the refugees in accordance with local political and socio-economic parameters while preserving their ‘Right of return’. Although the realization of this right has never been clearly clarified – from a revengeful return of all refugees to their homes to a peaceful repatriation limited to the territories of a Palestinian State – its principle has constituted a rallying political creed across the Arab world.

The host countries’ characteristics and interests, together with their particular stance vis-à-vis Israel, have conditioned the formal/informal status they have conferred on the Palestinian refugees: from formal citizenship in Jordan (except for the refugees displaced from the Gaza Strip) to statelessness (except for minor exceptions) in other host countries. From a socio-economic discriminatory regime in Lebanon to treatment on a par with the host population in the fields of employment and access to governmental services in Syria. And from repression in times of conflict with the PLO – in Jordan (1969-1971) and in Lebanon (1975-1989) – to routine relations revolving around a common de jure respect for the refugees’ Right of return.

The Agency

A common feature among the Middle East Arab host countries has been the ubiquitous presence of UNRWA. The Agency has played a crucial role in helping both the host countries and the refugee communities sustain the status quo pending the full resolution of the Israeli-Arab conflict. Its various services have first secured the survival and well-being of generations of refugees while cushioning their potentially adverse impact on the host economies.

They have also contributed to bringing about generations of educated Palestinian refugees who have played a crucial role in the development of the Middle East region in general. Over the years, UNRWA’s mandate has come to be interpreted by the refugees and their representatives as attesting to the international community’s commitment to their rights.

Political Vacuum

The 1993 Oslo Agreements between the PLO and Israel disrupted the political balance upon which the relations between the refugees and their host authorities were based. In the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the former have had to assert their right of return within the context of peace talks primarily focused on the creation of a Palestinian state. They have not questioned the need for the existence of such a state but have refused to sacrifice their cause in exchange. Because they did not want to bear the consequences of the refugees’ permanent resettlement on their territory alone, the Arab host authorities have also insisted on the refugees’ vested rights. However, this political stance has generally been paralleled by a tightening of the discriminatory legal status conferred formally or informally on the refugees.

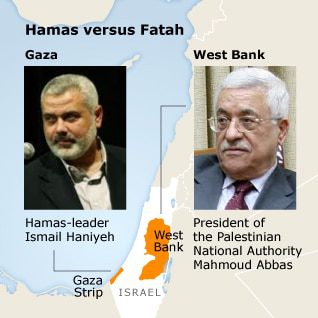

The increasing budgetary difficulties faced by UNRWA since 1993-1994, combined with the demise of the PLO social and economic institutions in the Diaspora, have further worsened the refugees’ living conditions and reinforced their concerns about their permanent status. The trend towards the rehabilitation of the refugee camps’ physical infrastructure across the Middle East since the late 1990s-early 2000s has done little to remove such concerns. Today, the refugees are trapped in a political vacuum. While the PLO, the institution in charge of the Palestinians, is dormant, the PNA in Palestine has been divided since 2007 between the nationalist Fatah movement (predominant in the West Bank) and the Islamist Hamas movement (in control of the Gaza Strip).