Settlements are Jewish-Israeli communities established on territories that Israel occupied during the 1967 June War. The Hebrew and Arabic words for a settlement, hitnahalut and mustawtana respectively, are loaded with deep ideological meaning.

Introduction

Settlements are Jewish-Israeli communities established on territories that Israel occupied during the 1967 June War. The Hebrew and Arabic words for a settlement, hitnahalut and mustawtana respectively, are loaded with deep ideological meaning. The choice whether or not to employ these terms is testimony to this controversy. Some use these terms for all Jewish communities built within the territory of the former British Mandate of Palestine (1920-1948). Others prefer to avoid using these terms, rather employing different words with fewer negative associations when referring to Jewish communities in the former territory of the British Mandate.

Photo Gallery – Israeli Settlements in the West Bank

The Armistice Agreements

The Armistice Agreements of 1949 established the so-called Green Line as the armistice line, which would serve as Israel’s unofficial border until 1967. In that year, Israel took over several territories belonging to its neighbouring countries: the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt; the Golan Heights from Syria; and the West Bank from Jordan. Later, settlements were established in these territories.

Over the years, Israel has withdrawn its forces from Sinai and Gaza; it also evacuated and demolished the settlements in these two areas.

Most of the settlements and settlers are located in the West Bank in Palestine. In light of the sensitivity of the issue of East Jerusalem, a West Bank area that Israel annexed in 1967, none of the statistics presented here about the number of settlements and settlers include East Jerusalem unless mentioned otherwise. Statistics regarding this area are presented separately, namely in the paragraphs on the settlements in East Jerusalem.

According to B’Tselem, a Jerusalem-based centre for human rights in the occupied territories, the number of Israeli settlements was 147 at the end of 2013: 125 of these were in the West Bank, 15 in East Jerusalem and seven in Hebron. The Israel Central Bureau of Statistics states that 400,000 settlers were living in the West Bank in 2015. This number does not include the 300,000-350,000 settlers in East Jerusalem. Neither does it include the so-called outposts in the West Bank, unauthorized settlements that are not officially recognized by the Israeli government. These number around 100 and are home to 5,985 people.

Dani Dayan, Chairman of the Yesha Council, an organization of municipal councils of Jewish settlements, put the total number of settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem at 800,000 in 2015. The settlements have grown significantly in the past two decades: 53,000 houses were built between 1993 and 2013.

The ICJ’s Opinion

An advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (6 May 2004) states that the settlements are illegal. While this position is accepted by the international community and its institutions, Israel has rejected the ICJ’s opinion.

Settlements are at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as they have a critical influence on the fabric of life in the West Bank. Over the years, this problem has always been defined as one of the core issues in negotiations between Israel and the PLO. As long as the various parties cannot reach agreement on the settlements, a political solution for the Middle East conflict remains out of reach.

Settlements and International Law

Since the middle of the 19th century, International Law gradually became a fixed and bounding standard for human rights as a whole, and specifically for the conduct of armed conflicts. The power of munitions in the possession of militaries of the modern era, and lessons learnt from the two world wars, have highlighted the need for such a standard, and its process of formation proceeds even today.

Armed conflict situations, including belligerent occupation, are subject to two main branches of International Law, namely International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL).

International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and Settlements

IHRL began developing in the aftermath of World War II. Its basic principles were first set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, and enshrined in two United Nations conventions in 1966. Israel signed and ratified these conventions. Two UN committees in charge of interpreting and monitoring the application of these conventions have ruled that they apply in any area over which a government exercises control, regardless of sovereignty. The International Court of Justice and the Israeli Supreme Court have recognized the application of this branch of International Law to Palestine, along with the IHRL.

The establishment and existence of settlements violate a long list of rights enshrined in these treaties, either directly or indirectly.

The right to self-determination is violated as a result of the settlements’ control over almost half of the lands of the West Bank, and the way they are spread through the territory to block the territorial contiguity of dozens of Palestinian towns and villages. This undermines the possibility of establishing an independent viable Palestinian state, even though such a state has been recognized by the international community as the right framework for exercising the right to self-determination.

The right to equality is violated as a result of the application of two separate systems of law of each of the two populations residing in the West Bank. While the Jewish-Israeli settlers are subject to Israeli civilian law, Palestinian residents living under occupation are subject to Israeli military laws. Granting different rights to different people residing in the same territory, in accordance with their national identity, is a blatant violation of the right to equality.

The right to property is infringed as a result of Israel taking over both public and private lands belonging to Palestinians. Granting lands for the good of settlements, and the blatant deviations from the rules of due process involved, violate this right.

The right to an adequate standard of living is also violated as a result of the establishment of settlements in the proximity of Palestinian towns and villages, thus restricting or preventing their expansion. In addition, taking over agricultural or pasturing lands has often harmed families’ livelihood and standard of living.

An infringement of the right to freedom of movement is caused by the fact that many settlements have been located next to main Palestinian roads. In order to protect settlements, Israel has often restricted the Palestinian movement on main roads. This policy reached a peak with the outbreak of the Second Intifada, in September 2000. The peak lasted up until 2009. The violation of this right also directly affects the rights to work, to health, to education, and to family life.

International Humanitarian Law

IHL, also known as the Laws of War, sets out the norms governing the conduct of armed conflicts and the obligations that bind all parties involved in such conflicts. The establishment of settlements violates two main treaties of IHL that list the provisions that apply in war and in occupation: the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. Israel signed and ratified both.

IHL Principles

The temporality of belligerent occupation is one of the basic principles of IHL. This temporality is the source of restrictions that apply to the occupying power creating facts on the ground in the occupied territory. The Hague Conventions set forth in Article 55 the rules governing the lawful use an occupying power may make of public property, including lands. A government may administer and even make use of public properties of the occupied country, yet it must not change their character or nature, unless it is done for military purposes or for the benefit of the local population. Three additional Articles in this treaty (46, 47, 52) defend the private property of people under occupation.

This has been the basis for different institutions and officials in the international community to assert that the settlement enterprise, which includes expropriation of lands, the establishment of settlements, and migration of Israeli citizens to them, is illegal.

Israel’s response

Israel has responded to this assertion in several ways. First of all, it has claimed that since the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were not under any recognized state sovereignty prior to Israel taking them over, these territories cannot be considered as occupied territories, and so the relevant treaties do not apply there.

This stand has been rejected by many institutions, states, and scholars internationally, and even by the Israeli Supreme Court itself. It has been argued that whether or not the laws of belligerent occupation apply there, depends on whether a state exercises effective control outside its territory, and not on the existence of previous sovereignty. This kind of dependence would have rendered the provisions pointless, since it is very often the case that the legal status of an occupied territory, in the past or at the present time, is disputed.

Israel’s additional argument has been that a permanent community is ‘no more than a relative term’. This argument has been rejected as well, since without a doubt, turning an open field into a populated civilian community is a dramatic and far reaching change. Considering this kind of change to be temporary would render the provision pointless.

Introducing Changes

As noted above, an occupying power may lawfully introduce changes to an occupied territory under certain conditions, notably, as long as this is done in favour of the local population or for military needs. Indeed, Israel has tried to claim that settlements were established for military needs. Yet, this assertion too, was not embraced by the international community, since even though it is possible to discuss the security cost and benefit of settlements from the Israeli point of view, it is quite clear that this has not been the reason for their establishment. In fact, this reasoning has been an attempt to make use of a military need as a disguise for political, ideological, and strategic motives.

Article 49 of The Fourth Geneva Convention states that the ‘Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies’. It has been claimed internationally that this article forbids the establishment of settlements. Israel, by contrast, has rejected this assertion, and claimed that ‘the movement of individuals to the territory is entirely voluntary’. This has been rejected internationally, for two reasons: first of all, because the prohibition is aimed at defending the local residents from the settlement of an alien population in their land; whether this migration is voluntary or forced is irrelevant. Second, the term ‘voluntary movement’ is, in this case, misleading. The will of Israeli citizens to go and live in Palestine would never have been realized in the absence of active state involvement in building and maintaining the settlements. It is the State of Israel that has grabbed the land and initiated, approved, planned, and funded the establishment of the vast majority of settlements. Israel also gives its citizens economic incentives to migrate to the settlements, and takes responsibility for their security.

On 6 May 2004, the International Court of Justice ruled, in an advisory opinion regarding the Wall, that the settlements as a whole were in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention and illegal because they violated the principle of temporality, harmed the local population, and led to severe resource and infrastructure discrimination.

Israel’s Settlement Policy

#1: Seizing Lands

Throughout the years, Israeli Jews have settled in the West Bank both on lands Israel allocated to them and on lands not allocated for their use, including privately owned Palestinian lands. In many cases, Israel retroactively legitimized, by bureaucratic means, the settling of Israelis in different areas.

During the first decade of the occupation, Israel seized lands in the West Bank mostly on the basis of a military order stating that ‘it was done for necessary urgent military needs’. The use of this justification was intended to legitimize the expropriation based on the International Law allowing the occupying power to make use of lands belonging to the occupied people as long as such a need existed. Initially, so-called Nahal Settlements – communities built and populated by Israeli soldiers of the Nahal Brigade – would be established on these expropriated lands, which Israel considered to be army bases. Later on, the Nahal Settlements became civilian communities.

Elon Moreh Case

In 1979, the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) issued a precedential ruling on this practice, in what became known as the so-called Elon Moreh Case. Following the ruling, there has been a dramatic decline in such orders issued by Israel in order to grab land and allocate it for settlements. However, land that had already been seized under this pretext was not, in the vast majority of the cases, returned to its owners. The Spiegel Database (named after Brigadier General Baruch Spiegel), a secret database prepared pursuant to a 2004 request by then Defence Minister Shaul Mofaz, and additional documents dealing with the matter, indicate that at least 31,000 dunams (based on the Ottoman 1858 Land Law; 7,660 acres) used for the establishment of 42 settlements were seized following this practice.

Yet, even though Israel almost completely halted the use of this method in order to establish new settlements, it has continued to make use of the aforementioned military order for seizing land for other purposes that are also for the benefit of the settler population. For example, it has used the order to pave new bypass settler roads. This method was applied mainly for the 1994 ‘redeployment’ following the approval of the Oslo I Accord.

Second Intifada

The outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000 brought about a new and wide wave of use of this practice. The need to protect settlers, who came under attack in that period, led Israel to pave new roads for them, to close off strips of land around settlements that in fact annexed additional large tracts of land to their territories. From 2002, Israel has widely used land seizure for military needs to facilitate the erection of the Wall, almost the entire length of which lies inside the West Bank.

‘State Lands’

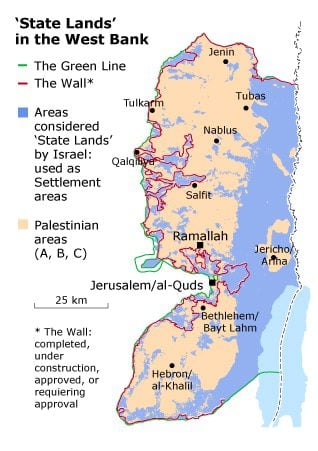

Following the 1979 ruling on the Elon Moreh Case, the State of Israel declared that it would expand existing settlements and establish new ones on ‘lands owned by the State’. Declarations on State Lands have since become the main means for grabbing land. With this aim, some 913,000 dunams (225,607 acres), or 16 percent of the West Bank, have been declared State Lands. The declarations have been made on the basis of the Ottoman 1858 Land Law. Some additional 600,000 dunams (148,263 acres) of the West Bank had already been declared as such during the British Mandate (1920-1948) and the Jordanian Rule (1948-1967). As of 2011, state lands in the West Bank amount to 1.5 million dunams (370,658 acres), or more than a quarter of the territory of the West Bank. Some 75 percent of the municipal jurisdiction areas of the settlements and about two thirds of their built-up areas are on lands defined as such.

The vast majority of these areas have been seized on the basis of the opinion of Attorney Plia Albeck, former head of the Civil Department in the State Attorney’s Office. According to her interpretation to the law, ‘what is not registered [in the Land Registration Of?ce] and is not cultivated land is state land’. This wide assertion regarding what may be considered state land is very different from the common interpretations of this law in the British and Jordanian times, and it is this new interpretation that has facilitated such an extensive expropriation.

#2: Economic Benefits and Incentives

Economic benefits and incentives granted by Israel to settlements are based upon the inclusion of most of them in the plan of so-called National Priority Areas. Residents and local authorities of communities defined as part of a National Priority Area get government assistance in many fields, including housing, education, industry, agriculture, and tourism. According to the stated goal of this assistance, it is meant to encourage a ‘continuing generation’ to stay in the community, to promote the long-term settlement there of Jews that have immigrated to Israel, and to push for the migration of residents from other areas, inside Israel, to move there. Generally speaking, such support is given to periphery communities that are relatively remote from Israel’s centre. This is not true of the settlements, most of which are close to central Israeli cities in the coastal plain and to Jerusalem.

Different ministries regularly cover up documentation of money allocated to settlements. Even official Israeli institutions, such as the State Comptroller who scrutinized the budget of the Housing ministry, have admitted that they could not compile the ‘budget share allocated to Judea and Samaria’ [the West Bank]. Thus, it is not possible to calculate the overall cost of these benefits.

Financial Support

Yet, clearly, the financial support for settlements is not compatible with the accepted parameters in other areas in which it is given, both from the perspective of the financial situation of the residents and from the perspective of the different status of the communities. This became especially obvious when, in an examination prepared by the Housing Ministry of the effects that the basket of goods had on communities receiving it, settlements were excluded from the calculation, which referred only to Israeli territory.

For instance, according to the Israeli Housing Ministry, 104 settlements are entitled for benefits of National Priority Areas. The ministry defines most of the settlements as ‘Priority A’, and thus they are entitled to receive the maximum support, including a 69 percent discount on the land value in leasing payments for housing construction.

The ministry also grants these settlements subsidies of up to 50 percent of the cost of developing infrastructure, and gives support in buying apartments by allocating subsidized mortgages.

The State Comptroller found that the Housing Ministry investment in 2000-2002 was 5.5 times higher than the parallel investment in other Priority A areas. Other Israeli ministries, such as the Education, the Industry and the Agriculture ministries, also grant various benefits and incentives to the settler population.

The Israeli economist, Shir Hever, found that while average annual per capita governmental payment for Israeli citizens in Israel’s territory amounts to 40,000 NIS (approximately 11,000 USD), the overall civil and security investment for settlers amounts to 93,000 NIS (approximately 25,800 USD). The relative share of these costs out of the entire budget is growing ever larger, since while the general Israeli population has grown at a rate of 1.8 percent annually, and the State Budget has grown at a rate of 2.3 percent, the settler population has grown at an annual rate of 7 percent.

#3: Two Legal Systems

As a part of the attempt to encourage its citizens to migrate to the West Bank, the Israel has made many efforts to ‘blur’ the Green Line. Many of these efforts manifest themselves in physical aspects, while in much of the territory it is simply impossible to tell where the border was in the past. In addition, these efforts are intended, in other, more subtle ways, to minimize the sense of separation of settlers from Israel.

Seemingly, the entire West Bank, apart from those lands annexed to Jerusalem, is under military rule, and all civilians that reside in this territory are subject to military law. Yet, it was in July 1967 that the Israeli Defence Minister issued a decree, based on Emergency Stipulations, that applied much of the Israeli Law to settlers. Time and again, since then, the Israeli Knesset has extended these provisions, according to which Israeli citizens that commit offences in Palestine are prosecuted in Israeli civilian courts.

This way, a twofold legal system came to be applicable in one single territory, the national identity of a resident being the criterion for the decision which legal system was to be applied. While Israeli citizens are subject to civilian law, military law applies to the Palestinians, who are the subjects of the occupation. The differences between the two legal systems are noticeable in each of the following stages: the length of detention permitted before letting the suspects see a lawyer or bringing them in front of a judge, the maximum punishment, the possibility of early release, and more.

According to International Law, as long as a certain territory is occupied, military law must be applied to all civilians residing there. A situation in which two people who commit the same offence are judged in two different legal systems and with different laws is a situation of segregation.

Gush Emunim

In addition to the national-security motivation behind the establishment of Israeli settlement in the West Bank, there is another motivation, no less meaningful, that combines the religious, historical, and national dimensions. In this national-religious front, Gush Emunim (Block of the Faithful) played a central and crucial role. It was a national-religious movement which was engaged in establishing, expanding, and promoting the construction of Israeli settlements, mostly in the West Bank. This movement was also active in the Gaza Strip until the Israeli withdrawal in 2005.

Gush Emunim was established in February 1974 in reaction to the crisis experienced by the Israeli society in the aftermath of the 1973 October War. Since its very beginning, Gush Emunim represented a unique mixture of values, rights and objectives, including Judaism, Zionism, the right of settlement, security and salvation.

Similarly, its members combined the central believes of the early Zionist movement, such as redemption of and settling in the Land of Israel, with a radical religious ideology that advocated establishing greater Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel); a religious imperative which was part of the implementation of an overall divine plan.

Ideological infrastructure

The ideological infrastructure of Gush Emunim was derived from the composition and combination of three key factors: the People of Israel, the Torah of Israel, and the Land of Israel. In their view, the People of Israel were essentially different from the rest of the nations of the world, a difference from which this people’s unique role derives.

They believed that the Jewish people’s mission derives from a divine biblical imperative, the adherence to which includes, among other things, settling in Eretz Israel. The latter extends over a much larger territory than the modern State of Israel. In the heart of Eretz Israel are the lands of the West Bank in which many of the constitutive events of the People of Israel took place.

Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, son and successor of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, was the main adjudicator and mentor for the leaders of the movement. About a month after the establishment of Gush Emunim, The Jerusalem Post published his call: ‘This entire Land is ours, completely, belongs to all of us.

It cannot be given to others, not even partially (…) hence once and for all, these matters are clear and absolute, that there are no ‘territories’ or ‘[Palestinian] Arabs’ or ‘Arab Lands’. Rather, it is all Jewish land, our eternal, ancestral inheritance.’

Basic standpoint

This view formed the basic standpoint of the members of Gush Emunim as far as Palestinian residents of the Land were concerned. They completely rejected any Palestinian demand for national expression in ‘Judea and Samaria’, and did not recognize the existence of a ‘Palestinian People’ as a collective.

However, there was no consensus amongst them on the best way of dealing with the existence of Palestinians in the area. One approach saw their expulsion as ‘first and foremost a Zionist mission, no less and perhaps even more important than settling Jews in the Land’, while others supported developing ‘relatively normal life, with neighbours, as long as they do not wave the national flag’.

Part of the secret of the movement’s strength was the dual attitude its members had towards the State of Israel. On the one hand, they considered it to be ‘a state from which the light of the Messiah bursts and rises’, in the words of Rabbi Haim Drukman describing Kook’s attitude eulogizing him, so that he ‘considered the tanks, the cannons and the aircrafts of the IDF [Israel Defence Force] to be religious objects, holy objects, for they serve the imperative of settling the Land of Israel’. On the other hand, at a similarly profound level, they perceived Israel, since it was a modern nation state, as a tool of which one should make use wisely.

This dual attitude also manifested itself in the political practices they used. They embraced the constituting ethos of the Zionist movement, and saw and presented themselves as the real heirs and successors of the founders of the State. They also maintained continuous contact with high echelons of the Israeli regime and worked gradually to integrate themselves into the central security, educational, and political institutions of Israel.

However, when they felt it necessary, they did not hesitate to engage in radical activism, including breaking the law and clashing with the Israeli security forces. This way, they expressed their determination and commitment to something larger and more essential than the framework of a state. This helped them to recruit new, young members and to gain influence over Israeli politicians who feared confrontation.

Right wing government

The establishment of the right wing government in 1977 introduced a change in the movements’ methods. The reduced need for putting political pressure on the government, since the latter held a similar ideology, brought about a decline in Gush Emunim’s activities as a popular protest movement and to the institutionalization of operational wings.

In 1979, they established Amanah, a wing of the movement in charge of the creation and support of new settlements. At the end of 1980, they established the Yesha Council, a non-governmental organization uniting heads of councils and mayors of the settler population.

Peace Now

An extensive survey conducted by Peace Now, an Israeli movement opposing settlements, indicated that, as of 2002, ‘ideological settlers’, historically identified with Gush Emunim, constituted some 40 percent of the West Bank‘s settlers. Some additional 30 percent were considered to be ‘standard of living settlers’, who had migrated to settlements from financial motivations and from motivations related to their quality of life.

Some additional 30 percent were ultra-orthodox Jews, who would rather live in the West Bank both for financial reasons and because of the possibility of living in homogeneous communities. In spite of the low number of ‘ideological settlers’ in relation to the overall number of the citizens of Israel, Gush Emunim has had a strong influence over the settlement enterprise and Israeli society as a whole, even years after the movement ceased to exist.

Settlements in East Jerusalem

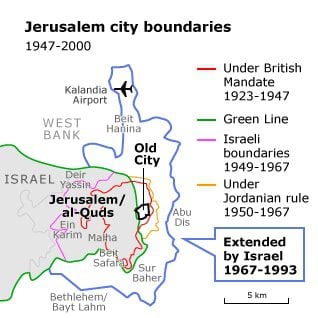

East Jerusalem is not a geographical term but rather a political one, having to do with lands that fall within the territory of the West Bank, east, north, and south of West Jerusalem. These lands were annexed by Israel to its territory seventeen days after the completion of the process of occupying the West Bank from the hands of the Kingdom of Jordan in 1967.

The so called ‘Jerusalem problem’ is considered to be the most sensitive and complex problem of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, since both sides consider this city to be their religious and historical centre, as well as their capital.

The 1967 War

On the eve of the 1967 War, West Jerusalem, as the capital of the State of Israel, spread over some 38 square kilometres, home to some 150,000 Jews. The Jordanian part of Jerusalem included at that point about 6 square kilometres, home to some 9,000 Palestinians. On 27 June 1967, the Knesset enacted a law stating that ‘[t]he Law, jurisdiction and administration of the State will take effect in every territory of Eretz Israel decided upon by the government in a decree’.

This encompassed 71.3 square kilometres, including so-called ‘Jordanian Jerusalem’ as well as 28 Palestinian villages around it. At the time, some 70,000 people resided in that territory. The application of the Israeli law on the newly annexed lands was carried out unilaterally, and was rejected by the international community and institutions.The next day, the government issued a decree applying this provision on a new municipal boundary, drawn up by a special committee.

Jerusalem Law

On 30 July 1980, the Knesset enacted the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, also known as the Jerusalem Law, which stated that ‘Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel’. This merely symbolic declaration was followed by a swift condemnation by the UN Security Council. On 20 August 1980, the Security Council ruled the law invalid and a violation of International Law, with fourteen members supporting it and only the United States abstaining.

Settlements Classification

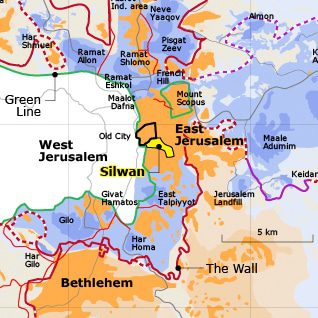

Settlements in East Jerusalem can be classified into two: the so-called new neighbourhoods, established by the Israeli governments, and enclaves of small settlements, established in the heart of Palestinian neighbourhood and villages, mostly in and around the Old City.

Since 1967, the government of Israel has pursued two objectives: to make sure East Jerusalem does not turn into the Palestinian capital, by isolating it from the rest of the West Bank; and to preserve a Jewish majority in Jerusalem’s new borders by wiping out the Green Line and encouraging migration of the Jewish population to the Eastern City. To this end, Israel has expropriated some 30 percent of the annexed lands, and established 12 large new neighbourhoods in them. The regime and the vast majority of the Israeli public do not consider these neighbourhoods as settlements but rather as a inseparable parts of the city.

The International Community

The international community sees this area as part of the occupied territory, the future of which should be determined through negotiation. However, different proposals for settling the conflict, including the Geneva Initiative and the Clinton Parameters, accept the reality created on the ground and state that ‘the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and Jewish ones are Israeli’.

According to these proposals, the division of Jerusalem will not be carried out following the track of the Green Line, but rather the territory of the Jewish neighbourhoods staying in the hands of Israel would be counted as part of the ‘land swap’ calculation.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Israeli regime prevented the establishment of Jewish enclaves in the heart of Palestinian neighbourhoods in the city, but in the nineties, this changed in the context of the Oslo Accords in the middle of that decade, during which the question of Jerusalem was also discussed.

Those who opposed the division of the city responded by increasing their efforts to create facts on the ground that would hinder this process, while focusing their activities on the Old City and the holy basin, which are at the heart of the disagreement. These settlements have typically been established by private non-governmental settler organizations, though they receive incentives and support from the government.

The Elad Association

The neighbourhood of Silwan, right next to the Old City and home to some 40,000 Palestinians, illustrates this well. The Elad Association (a Hebrew acronym for: ‘To the City of David’, the historical Jewish name for this area) began its activities in the nineties by attempting to settle Jews in the area. The purpose of this practice was defined by Adi Mintz, a member of the Elad administration, in an 23 April 2006 interview in Haaretz: Our goal is ‘to get a foothold in East Jerusalem and to create an irreversible situation in the holy basin around the Old City’.

Elad’s national and religious motivations have been compatible with the intentions of central officials in the Israeli administration. The government support they received included, among other things, an exceptional granting of a license to operate a national park, and the allocation of tens of millions of NIS from the budget of the Housing Ministry in order for them to fund a private security company safeguarding settlers in and around Silwan.

In spite of the relatively small number of settlers in these enclaves, reaching some two thousand residents in 2010, their influence on the situation in Jerusalem is strong, both because of the continuous friction between them and the Palestinian population, and the high sensitivity of the places in which they chose to settle.

By the end of 2008, some 456,000 people resided in East Jerusalem. These constituted about 60 percent of the residents within the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem. Approximately, 195,500 or 43 percent of them were Jews, and 260,800 or 57 percent were Palestinians.