Israel’s policy towards Jewish settlements indicates that it uses settlements to undermine any future agreement with the Palestinians.

Before 1967

Before 1967, the Green Line – established in the 1949 Armistice Agreements – was in fact the eastern border of Israel. Back then, Israel‘s territory encompassed 78 percent of the land of the pre-1948 British Mandate for Palestine.

However, neither Israel nor its neighbouring Arab states had ever recognized the borders of this territory as a formal state border, although most of the international community did in fact consider the Green Line as such.

After 1967

On 5 June 1967, war broke out between Israel and its neighbouring states, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, who were supported by other Arab states. During the war, Israel conquered the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights – thus gaining land three times larger than its pre-war territory. From these territories, Israel annexed the Golan Heights and lands in and around (former Jordanian controlled) East Jerusalem, and applied its laws to these territories.

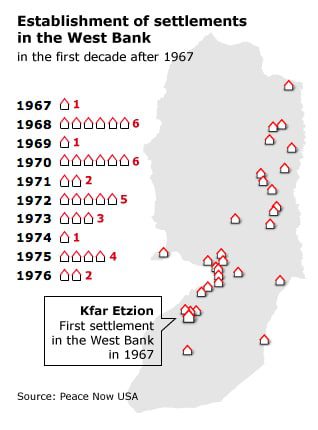

On 14 July 1967, about a month after the war ended, the United Kibbutz Movement established the first Jewish settlement in Palestine, Kibbutz Merom Golan located on the Syrian Golan Heights. On 27 September 1967, the first West Bank settlement was established – Kfar Etzion – as a result of pressure put on the Israeli authorities by a group of Israeli citizens, including families that had lived in the area prior to the 1948 war, when their community had been driven out.

Generally speaking, in the aftermath of the 1967 war, the Israeli government did not have a clear stand on settling Israeli nationals in Palestine (except in East Jerusalem, see below). Most of the Israeli ministers were opposed to such settlement because they wanted to use the Occupied Territories as bargaining chips for future negotiations. However, this position changed quickly.

The Allon Plan

On 13 July 1967, Israeli minister Yigal Allon, who chaired the Ministers’ Settlement Committee, submitted to the government a proposal for ‘the future of the Territories and the ways to handle refugees’. It was a strategic plan intended to expand Israel’s territory, arguing that such an endeavour was indispensable for maintaining the security of Israel. The original Allon Plan suggested establishing Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley and the southern desert areas of the West Bank in order to ensure a Jewish presence in regions with no dense Palestinian population, and as a preliminary step towards formal annexation.

The Allon Plan – expanded in 1970 to include about half of the West Bank – has never been formally approved by the government.

However, during the first decade of the occupation, this plan served as a basis for the actions of the Israeli governments headed by Labour-dominated governments, until the Likud party came to power in 1977. During that first decade, the government of Israel initiated the construction of nearly thirty settlements, home to some 4,500 people, most of which were in areas included in the Plan.

The aftermath of the June War of 1967

Internationally, two major events happened in the aftermath of the 1967 war: on 1 September 1967, the leaders of eight Arab states, in a summit in Khartoum, Sudan, called for the continuation of the struggle against Israel in order to ‘ensure the withdrawal of the aggressive Israeli forces from the Arab lands which have been occupied since the aggression of June 5’. In spite of the harsh tone of the Khartoum Resolution, some considered it to be the first time Arab leaders had pursued diplomacy to recover Israeli occupied lands, and even the first time they had in fact recognized Israel in its previous borders. On 22 November 1967, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 242, the main thrust of which was a call for Israel to withdraw from territories it had occupied during the war. (See more on this issue in the paragraphs discussing International Law.) The resolution, adopted unanimously, set the conditions for reaching peace between Israel and its neighbours, and in fact recognized the Green Line as an agreed upon border, unlike the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, adopted by the General Assembly on 29 November 1947 (Resolution 181).

The Likud party

After the Likud party formed a government in 1977, Matityahu Drobles, chairman of the settlement department in the World Zionist Organization (WZO), prepared a comprehensive time-framed plan for settling throughout the West Bank. The WZO is a non-governmental organization established in 1897 that receives financial support from the Israeli government and in fact serves as a wing of the Israeli government for the establishment of settlements.

The Drobles Plan stated that the ‘civilian presence of Jewish communities is vital for the security of the state (…). There must not be the slightest doubt regarding our intention to hold on to the areas of Judea and Samaria [West Bank] forever (…). The best and most effective way to remove any shred of doubt regarding our intention to hold Judea and Samaria forever is a rapid settlement drive in these areas.’

Ariel Sharon, then Minister of Agriculture and chair of the Ministers’ Settlement Committee, also defined most of the West Bank as indispensible for the security of Israel, and considered the establishment of settlements as a preliminary measure towards their annexation. A plan he submitted to the Israeli government on 29 September 1977, called for the creation of a buffer between Palestinian communities from both sides of the Green Line, as an important means for bringing about a change in the route of the borders.

Economic incentives and proximity to the Green Line made it easier for the government to attract Israeli citizens seeking to improve their standard of living to the settlements.

The implementation of the Drobles Plan, on the other hand, was intended to be taken forward mainly by members of Gush Emunim (see below), driven by strong ideology, who did not hesitate to settle in the West Bank ‘Mountain Strip’, which was densely populated by Palestinians.

Israeli-Egyptian peace talks

During the Israeli-Egyptian peace talks in the late 1970s the leaders of both states decided to open negotiations on the creation of a plan for autonomous governing for the Palestinians, a political construction rejected by the PLO. The program, presented by Israeli Likud Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, towards the end of 1978, denied the institution of a Palestinian state while calling for the settling of Jewish-Israeli citizens in the West Bank. The approval of the Jerusalem Law by the Israeli Knesset, on 30 July 1980, stating that ‘Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel’, and the assassination of the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat (6 October 1981), brought the discussions of this plan to an end.

The Drobles Plan

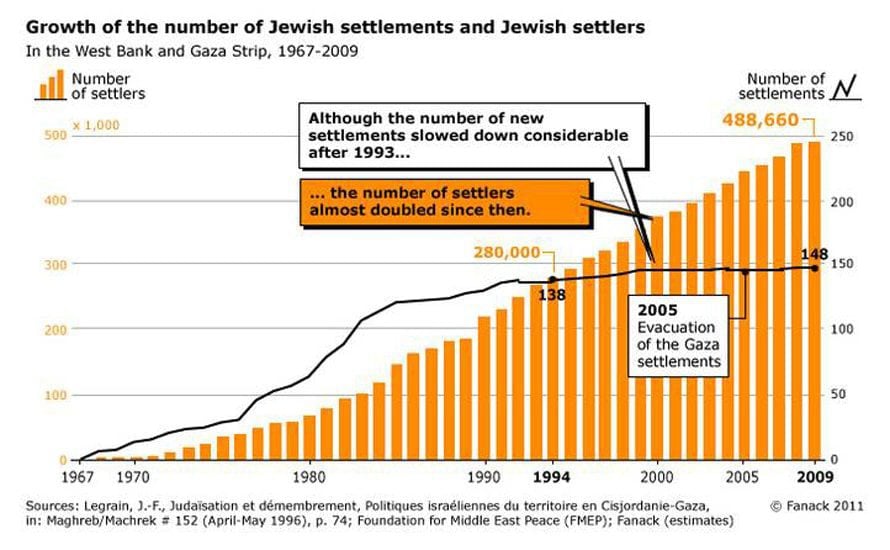

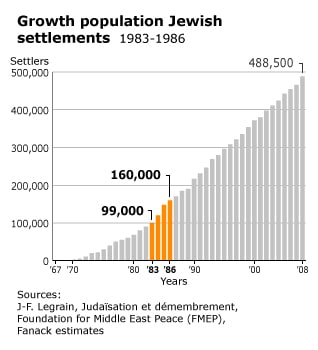

In 1983, following the expiration of the Drobles Plan and with the West Bank already housing about 22,800 settlers, the Likud government and the WZO published the so-called Hundred Thousand Plan, a new master plan for the settlements that set this figure as a goal for the total number of settlers that would reside in the West Bank by the end of the next three years. While the government established 23 new settlements during that period, as planned, it failed to reach the number of settlers decided upon, which by the end of 1986 amounted to approximately 51,000.

The First Intifada

The outbreak of the First Intifada on 6 December 1987 was a clear sign of the refusal of Palestinians to accept the occupation any longer. The Palestinian uprising and the determination of the Israeli government to raise the total number of settlers brought this issue to the centre of the international arena.

King Hussein’s decision

On 31 July 1988, King Hussein of Jordan announced his decision to give up all Jordanian claims on the West Bank. His announcement supported the Palestinian demand for recognition of their right to self determination. Three and a half months later, on 15 November 1988, the Palestinian National Council (the parliament of the PLO) adopted the so-called Algiers Resolution, in which UN Resolution 242 was embraced, implicitly recognizing the State of Israel. In 1991, following the failure of long diplomatic efforts, American president George H.W. Bush declared he would conditionally give Israel loan guarantees if it agreed to freeze settlement construction. This crisis in relations between the two governments was one of the main reasons for the Labour party winning the 23 June 1992 elections and the Likud government having to step down. This was the only time that the Americans sanctioned Israel for building settlements.

The Labour Party

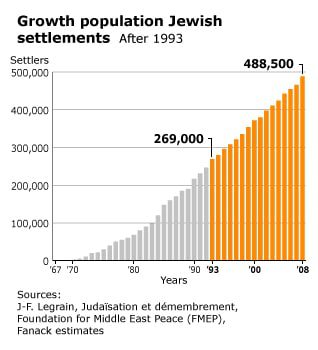

On 13 July 1992, the Labour government headed by Yitzhak Rabin was formed. Before the elections, Rabin had promised to ‘change national priorities’ and drastically reduce investment in settlements. The establishment of this government created the impression that the Israeli settlement enterprise in the West Bank would stop or merely slow down; the signing of the Declaration of Principles (Oslo I) by Israel and the PLO on 13 September 1993 made this impression even stronger. However, the declaration signed on the lawn of the White House said nothing explicit about settlements. In fact, the only reference to this major issue was an agreement to discuss it during the so-called final status negotiations. Until a permanent agreement is reached, it read, ‘Israel will continue to be responsible for external security, and for internal security and public order of settlements and Israelis’.

Oslo II

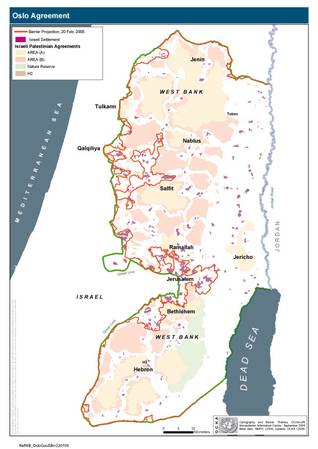

Two years later, in the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (Oslo II), signed on 28 September 1995, it was decided that ‘[n]either side shall initiate or take any step that will change the status of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip pending the outcome of the permanent status negotiations’. In addition to this article, the government of Israel promised the American administration that it would not set up new settlements and would halt expansions in progress. Yet, this promise was restricted: Israel said it would nevertheless respond to the so-called ‘natural growth’ needs of the existing settlement population. Therefore in some big areas it would not apply this commitment, and it would allow the completion of nearly 10,000 apartments whose construction had already started during the previous government’s term.

Clinton Parameters

On 12 December 2000, during negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians in Washington, a proposal for solving the conflict was read to the two sides. This proposal, which became known as the Clinton Parameters, included the idea of ‘exchange of territory’ or ‘land swap’.

This formula was based on two principles: using the Green Line as a basis for determining the final status borders, and recognizing ‘facts on the ground’, namely settlements, as a factor to be taken into consideration while determining these borders.

The Clinton Parameters suggested that the Palestinian state would be established on about 94 to 97 percent of the West Bank. According to the Parameters, the ‘settlement blocks’ – home to some 80 percent of the settlers – would be annexed by Israel. As compensation, pre-1967 Israeli territory would be added to the Gaza Strip.

Even though the negotiations mediated by President Bill Clinton failed, the ‘land swap’ principle has not disappeared. An indication of that fact was given when in January 2011, the al-Jazeera network published documentation of parts of the negotiations held during 2008 by the Israeli government under Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and high ranking PLO/PNA officials. The documents revealed that the talks between the sides on the final borders were also based on the ‘land swap’ principle.

The Second Intifada

On 27 September 2000, after another round of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations in Camp David (ever since called Camp David-II) had ended in a failure, the Second Intifada broke out in the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank.

The failure of the talks, as well as the fact that settlement activities were continuing at full pace, were the main causes of this next round of bloodletting, which was particularly violent this time. On 7 March 2001, Ariel Sharon from the Likud party replaced Barak as prime minister.

Sharon had been considered for many years to be ‘the architect of settlements’ and a central driving force behind their establishment. His coming to power was a sign that this era of negotiations was to be replaced with a unilateral Israeli policy.

In fact, during the years between the approval of the Oslo I Accord and September 2000, the total number of settlement housing units in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip increased by 54 percent. During these seven years, the number of settlers increased from 100,500 to 191,600, an increase of almost 90 percent. The peak of this growth was in 2000, under the rule of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and the Labour-Shas coalition government.

The Wall

Yet, it was at the end of Barak’s term as prime minister that the Israeli government decided to erect a barrier to separate Israel from the West Bank (hereafter ‘the Wall’). Frequent suicide attacks against Israelis and a sense of being at an impasse led most of the Israeli public to support the construction of the barrier. Newly elected Prime Minister Sharon, who at first was opposed to the project, believing it would endanger the future of the settlement enterprise and of Israel’s hold of the West Bank, eventually embraced the idea. However, the route set for the Wall coincided with the Green Line only to a very limited extent.

A major reason for the Israeli government to set the Wall’s route as it did was the intention to leave on its western side as many settlements as possible. This decision meant erecting the Wall inside the West Bank and in fact annexing the lands on its western side to the State of Israel. It also meant the route would be much longer than the previous border. While before 1967, the length of the border between the West Bank and Israel was 313 kilometres, the route decided upon for the Wall extended to 812 kilometres (as of January 2011). 8.6 percent of the West Bank lies on the western side of the Wall, containing 49 settlements, home to some 190,000 settlers. As of January 2011, Israel has completed the construction of 515 kilometres of the Wall, while 45 kilometres of the Wall are still under construction.

In 2004, the Wall was at the centre of concern and criticism in the international arena, when the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the Hague, scrutinized the question of its legality. On 6 May 2004, the ICJ published its advisory opinion on the matter, ruling that all settlements were illegal. In addition, the court held that the construction of the Wall deep inside the West Bank was in violation of international law. The ICJ called upon Israel to refrain from building the Wall inside the West Bank, as well as to dismantle sections already built there, and to compensate Palestinians for material losses. Israel, supported by the United States, rejected the court’s opinion.

The Roadmap

In April 2003, the so-called Quartet, composed of states and international and supranational entities involved in mediating in the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations (the UN, United States, European Union, and the Russian Federation), introduced the ‘Performance-Based Roadmap to a Permanent Two-State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’. As a first step towards a progress in negotiations, the Quartet put forward its demands for both sides, the main elements of which included a halt to Palestinian armed attacks and to Israeli construction in settlements. The latter demand explicitly included construction for the so-called ‘natural growth’, and the immediate dismantling of outposts established after March 2001, when the Sharon government was sworn in. (For years Israel had used ‘natural growth’ widely so as to include in this term the migration of new settlers to the territory.) In spite of repeating statements regarding its commitment to the Road Map, construction of the settlements proceeded, and the government of Israel refrained from dismantling the new outposts.

The new Road Map schedule stated that the conflict should cease by the end of 2005. As of 2011, more than five years later, it can be assumed that the main effect of the Road Map has been driving Prime Minister Sharon to push forward his own initiative, later known as ‘the Disengagement Plan’.

The disengagement plan

On 19 December 2003, Israeli Prime Minister Sharon announced his plan to withdraw from the Gaza Strip. That meant the evacuation and destruction of settlements and army bases in this region and the retreat of Israeli forces to the border of 4 June 1967. Sharon’s statement was received with surprise, as he had been a major driving force of the settlement enterprise in previous decades.

Dov Weissglass, who served as Sharon’s bureau chief, told Haaretz (6 October 2004) about the reasons leading to this change: ‘The disengagement plan is the preservative of President Bush’s formula (…) It gives us just about the right amount of formalin so there isn’t any political process with the Palestinians’. Weissglass added, ‘as for the big blocks [of settlements] the Disengagement brought about a situation in which we have a first of its kind American statement that they will be part of Israel’. Weissglass noted that ‘Ariel [Sharon] can sincerely say that there is a serious move here, that will enable 190,000 out of 240,000 settlers not to move from where they are’.

This perception was well based. On April 14 of that year, American President George W. Bush wrote in a letter to Prime Minister Sharon: ‘In light of new realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli population centres, it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949 (…) It is realistic to expect that any final status agreement will only be achieved on the basis of mutually agreed changes that reflect these realities’.

In mid-August 2005, Israel retreated from the Gaza Strip. This move included the evacuation of 22 settlements, home to some 8,600 civilians, as well as four settlements in the northern part of the West Bank. The political debate in Israel about the Disengagement Plan led to unprecedentedly extensive protests. However, the actual evacuation of the settlement went smoothly and lasted no more than eight days.

Though Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, it still maintains full control over the borders, as well as the aerial and maritime spaces of the Gaza Strip and is, according to international law, still responsible for the situation there.

Continued expansion of settlements

Israel’s policy towards Jewish settlements in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem in recent years indicates, according to Israeli leftist group Peace Now, that it uses settlements to undermine, or render impossible, any future agreement with the Palestinians.

The area intended to form a future Palestinian state has been reduced and fragmented by the continuous construction in settlements, deemed illegal under international law, in addition to the demolition of Palestinian homes and the displacement of Bedouins.

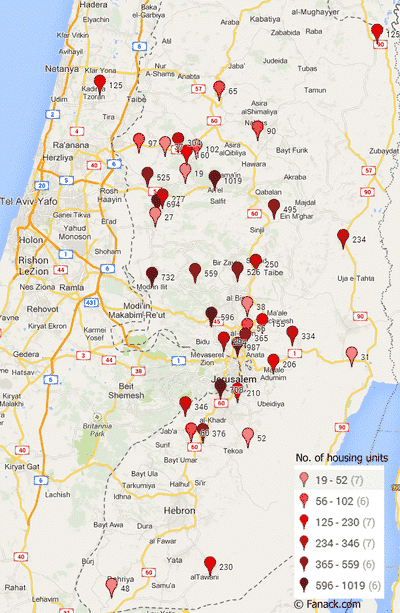

Official figures on construction in the West Bank make clear that settlement construction has surged in the past three years. Construction began with 738 units in 2010 and 1190 units were started in 2012 and 2580 in 2013. In 2013, 2895 units were already under construction, and the pace of construction reached a ten-year high (5000 units were built under the Barak government in 2000).

64 percent of the construction starts were public housing, a figure much higher than in Israel. This indicates the huge efforts the government is making to build in the West Bank, as contrasted with Israel, where Israelis have often complained about a shortage of public housing. These data do not include construction without permits in “illegal” outposts or construction in East Jerusalem.

Continuing settlement expansion during the 2013-2014 negotiations

The continuing construction in settlements has undermined chances of a diplomatic solution to the Israeli-Arab conflict. The latest round of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians, led by US Secretary of State John Kerry between August 2013 and April 2014, was overshadowed by the continuing Israeli settlement activity in the occupied West Bank, which was the main reason for the failure of the negotiations in 2010.

This time, although Israel had committed to halt construction in the settlements during new negotiations, Israel repeatedly announced new approvals of construction in settlements in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

During nine months of negotiations, the Israeli government promoted plans and solicited tenders for at least 13,851 housing units, an average of 1,540 units per month (50 per day), 73 percent of which involved construction in what Peace Now calls “isolated settlements,” which would have to be evacuated under a future peace agreement. The fact that Israel continues construction in these areas makes clear that the Israeli government does not intend to reserve land for a future Palestinian state but instead seeks to strengthen Israeli control over the area.

The approval of new housing units, the issuing of tenders for construction, and the planning of new construction (comprising several phases in the bureaucratic process) have been condemned by the international community. In November 2013, the UN condemned the Israeli approvals and warned against any measures that would undermine continuing negotiations.

The European Union has called the Israeli settlement policies “the biggest single threat to the two-state solution.” The repeated Israeli announcements of new construction in settlements have led the Palestinian delegation to threaten to withdraw from the talks as a whole. The PaIestinians, backed by the international community, are concerned that the expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem will threaten the viability of a future Palestinian state as part of an agreement between the two sides.

Critics of the Israeli government, including Peace Now, have repeatedly asserted that Israel is not serious about peace talks with the Palestinians. They argue that Israel has been using the negotiations as a cover to legitimize its settlement expansion and is unwilling to freeze its settlement enterprise.

Israeli response to Palestinian political reconciliation: More construction

In June 2014, two months after the negotiations had broken down, Israel responded to the new Palestinian unity government following the reconciliation agreement between Hamas and PLO by announcing more construction in settlements throughout the West Bank.

In what right-wing Housing Minister Uri Ariel termed a “proper Zionist response to the establishment of the Palestinian terror cabinet,” the government announced tenders for 1500 new housing units in the West Bank. Prime Minister Netanyahu also reactivated the planning process for 1800 units that had been frozen while the negotiations continued.

In response, Palestinian officials have vowed to appeal to the UN Security Council and General Assembly to take action against settlement construction. With the Palestinian accession in April to 15 international treaties and conventions (among them the Geneva Convention), other options to mobilize the international community against the Israeli settlement drive have become available.

The decision of the Israeli government was criticized by the international community, and, following pressure from Western European diplomats, Israel decided to delay plans for most of the 1800 units, although plans approved during the nine months of negotiations are still in the pipeline.

Under pressure

Netanyahu, as head of the most right-wing Israeli government in years, which includes a substantial number of pro-settlement ministers, is under pressure to sustain the settlement enterprise. 29 of 37 cabinet members are from either Likud/Yisrael Beteinu or HaBayit HaYehudy (Jewish Home), parties that support Israel’s settlement drive.

The Defense and Housing Ministries in particular, which approve construction in the West Bank, are headed by ministers who support construction in the settlements. Housing Minister Uri Ariel, a Jewish settler and a member of Jewish Home, is one of the Israeli cabinet’s foremost opponents of a diplomatic solution that would lead to evacuation of settlements and the creation of a Palestinian state.

The government is also under pressure from the settler lobby (Jewish Home voters) to look out for the settlers’ interests. During the latest round of negotiations, every time Israel announced the release of Palestinian prisoners as part of the negotiations, it almost simultaneously announced approvals of new construction in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

Growth

Israel legitimates the expansion of its settlements by reference to “natural growth”—that is, to the requirement that it accommodate the needs of the rapidly expanding settlement population. Population growth in the settlements on the West Bank (referred to by Israeli authorities as Judea and Samaria) is indeed far higher than in Israel proper.

Population growth in the West Bank was 5 percent in 2012, while growth in Israel was only 1.7 percent, according to data of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Settler subsidies, which the Israeli government uses to encourage Israelis to move to the settlements, are a major reason for the population growth.

Furthermore, Israel argues it is only building in areas it expects to keep in any future deal, the so-called settlement blocs (under the Geneva Initiative), but Israel has also approved construction in isolated settlements far from the Green Line (border resulting from the 1949 Armistice Agreement), which will be evacuated in case of a two-state solution.

Settlement construction in these parts of the West Bank far from the Green Line is therefore particularly sensitive, but construction in both the settlement blocs and deep in the West Bank is contrary to international law. It violates the Hague Convention of 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, which list the provisions that apply in times of war and occupation.

Currently, about 547,000 Jewish settlers live in settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem (according to the CBS and Peace Now, based on the latest data available). These settlements range from a small group of house trailers on a hill-top (the so-called “illegal outposts”) to medium-sized towns, such as Maale Adumim (population in 2012 36,862), with many facilities.

Outposts as cover for settlement expansion

While the prospect of an Israeli retreat to these settlement blocs as part of a final status agreement has become part of the diplomatic narrative, Israel has, in addition to approving construction in settlements, facilitated the growth and consolidation of so-called illegal outposts established since 1996 throughout the West Bank.

Despite the Oslo Agreement and an international climate unfavorable to settlement construction, Israel has, since 1996, enabled and supported the construction of such outposts in the West Bank, disregarding its obligations to stop settlement growth.

These outposts lack government permits and proper planning and are often built on private Palestinian lands. The first outposts appeared in the summer of 1996, in the middle of the West Bank, in an area that would potentially become a Palestinian state. By calling them “illegal outposts,” the Israeli government distances itself from further illegal construction.

While illegal under Israeli law, the authorities have played a key role in the construction of new outposts and facilitated the infrastructure required by the outposts. Moreover, outposts serve the same goal as “authorized” settlements: continuing the expansion of the settler presence in the West Bank, thus establishing facts on the ground to complicate Israeli withdrawal in any future permanent agreement.

Israel in April 2003 committed itself to freeze settlement construction and demolish all outposts built after 2001. Based on the Roadmap, brokered by the Quartet (United Nations, European Union, United States and Russia) and approved by the UN Security Council and the Israeli Knesset, Israel would freeze all settlement activity, including the natural growth of settlements, and dismantle all outposts erected after March 2001.

During the Annapolis Conference in November 2007, prime ministers Abbas and Olmert signed a joint declaration reaffirming the parties’ commitment to their obligations under the Roadmap.

However, the settler population in the West Bank has only grown since then. The number of settlers in settlements and outposts in the West Bank increased from 488,600 in 2009 to more than 547,000 in 2012 (figures from Peace Now and B’Tselem, The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories).

According to the Foundation for Middle East Peace, Israeli commitments to evacuate these outposts have not been honored. The Israeli Civil Administration demolished only 19 structures in outposts in the 2011 and 2012, the last period for which figures are available.

In 2013, there were about 94 outposts scattered through the West Bank, with a total population of around 8000, according to the latest available data.

Legalizing outposts

In May 2011, the Netanyahu government declared its new policy on outposts in response to petitions to Israel’s High Court by Peace Now, Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, and Palestinian organizations. Illegal construction (the focus of the petitions) that was deemed to be on state land would be approved, and construction on private Palestinian land would be dismantled.

Since 2011, ten outposts have been legalized, five of which were erected after 2001 and thus had not been demolished under the Roadmap obligations. According to Peace Now, it was the first time that the Israeli government had decided to establish new settlements since 1990, when it legalized the settlements of Sansana, Rechelim and Bruchin in April 2012.

In addition, Israel enabled the establishment of new settlements without requiring an official decision to establish a new settlement. In this way, Israel has circumvented its obligations to build no more settlements and has been able to avoid international condemnation. Outposts have also been legalized as “neighborhoods” of existing settlements, under the pretext of accommodating the natural growth of these settlements.

By doing so, the Israeli cabinet does not have to place a request to the Knesset for the legalization of an outpost, which would attract negative international attention. In reality, even though they have been placed under the jurisdiction of adjacent settlements, many outposts are too far away from the latter to be considered part of existing settlements.

An example of such a “neighborhood” is Nofei Nehemia. It was legalized as a neighborhood of the settlement of Rehelim in April 2012, after Israeli authorities issued a military order officially establishing the boundaries of Rehelim (which had also been legalized); Nofei Nehemia turned out to be within the boundaries of Rehelim, but in reality, Nofei Nehemia lies about two kilometers from Rehelim and is not physically part of that settlement.

Leshem, a new outpost hailed by the Israeli Army Radio in August 2013 as “the first official settlement in twenty years,” is considered officially a neighborhood of the nearby settlement of Alei Zahav, but it is marketed as a new settlement, and not as an extension of Alei Zahav.

These retroactive legalizations (i.e., legalizations of outposts after they were built) are the last step of covert official support for outpost construction. Before legalizing outposts, Israeli authorities supported the construction and expansion of infrastructure and homes.

According to a study by the Alternative Information Centre and the UNESCO Chair on Human Rights and Democracy, 43 percent of the West Bank has been allotted to settler organisations and is off limits to Palestinians. While claiming not to construct new settlements, the Israeli government has gone to great lengths to halt the demolition of outposts and has continued outpost construction and development.

Outposts have been planned by regional Israeli councils, with the support of the World Zionist Organization and several ministries, including the Ministry of Construction and Housing and the Ministry of Agriculture. This covert assistance in the construction of outposts was uncovered in the 2005 Sasson report (Hebrew/English), in which Israeli attorney Talia Sasson revealed how ministries were hiding their involvement in outpost construction.

Most recently, after the killing of three kidnapped Jewish settlers in June 2014, settlers erected three new outposts, one of which, Ramat HaShlosha (‘Hill of the Three’) was named after the three teens.

As opposed to earlier cases where following such an attack settlers put up tents and called it an outpost, this time the municipalities supplied trailer homes and electricity and water infrastructure.

Another indication of official support for establishing new outposts is the fact that the official website of the Gush Etzyon Municipality called upon the settlers to come guard the place, and in Kiryat Arba, the mayor took part in establishing the outpost, according to Peace Now. The organisation has accused the settlers of exploiting the situation in the aftermath of the murders to advance building plans.

Barack Obama

When Barack Obama was elected as American President in 2008, he publicly promised to promote Israeli-Palestinian negotiations and to make efforts towards the establishment of a viable Palestinian state. As part of these efforts, the President embraced the Palestinian demand for an Israeli commitment to halt construction of settlements in the West Bank during the negotiations.

In November 2009, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of the Likud party agreed to this demand and announced a freezing of the construction for the duration of ten months. However, the various reservations and exceptions that were added to this announcement, namely the completion of construction works that had begun just prior to the announcement, led to the so-called ‘freezing’ having little and almost no influence. After ‘the freeze’ expired, the Netanyahu-government refused Obama’s call for an extension.