The unfolding of the Arab-Palestinian-Israeli conflict from the October War of 1973 to the signing of the Oslo Accords.

The October War of 1973

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict became more and more intertwined with the Cold War. The Soviet Union strengthened its ties with Egypt and Syria. In November 1971, Washington produced a memorandum of understanding with Israel, concerning military aid and coordination of policy.

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict became more and more intertwined with the Cold War. The Soviet Union strengthened its ties with Egypt and Syria. In November 1971, Washington produced a memorandum of understanding with Israel, concerning military aid and coordination of policy.

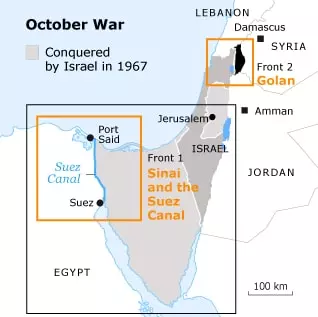

The political stalemate prompted Egypt and Syria to try to force a breakthrough by military means. On 6 October 1973, both countries undertook a coordinated surprise attack on Israel aimed at regaining territory lost in 1967.

The exact background of why and how the Arab forces were able to trick Israel into believing that massed troops had only left their bases for large war games, remains subject for academic debate and wild speculation. Israeli generals are said to have suffered from ‘cognitive closure’, a term describing the human inclination to eliminate ambiguity and arrive at definite conclusion.

It was even rumoured that President Nasser’s son-in-law Ashraf Marwan was a Mossad agent who had failed to inform his spymasters in Tel Aviv what was afoot because he had been ‘turned’ again. Conventional wisdom has it that Israeli military intelligence kept thinking it was very unlikely the Arabs were, six years after total defeat, capable of complex deception combined with an even more complex offensive, thus ignoring the multiplying signs that an attack was imminent. To be on the safe side, some Israeli armed forces were put on alert status.

Sinai

Only after a pilotless Firebee drone returned on the morning of Saturday 6 October 1973 from the Suez Canal zone with irrefutable evidence that the large-scale surprise offensive was only hours away, did the message hit home.

Total mobilization was declared, but that took time since many Israeli soldiers were on leave for Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), a holy day on the Jewish calendar and a national holiday. Time, there was not. Tens of thousands of Egyptian troops crossed the Suez Canal with amphibious vehicles and bridging equipment.

With large water pumps they hosed down the high sand barrier on the Israeli side and soon convoys of armoured vehicles trundled through the gaps. Opposing them were only hundreds of Israeli troops positioned in bunkers, who were quickly overrun.

Israel had always put trust in its air power to quickly destroy any Arab offensive that threatened the country.

In this respect the occupied territories, the Golan and the Sinai served as strategic depth. However, the Egyptians had anticipated the quantitative and qualitative edge the Israeli air force enjoyed over the Arab pendants. The Egyptian troops were protected by the latest Soviet air defence equipment, including modern mobile Surface to Air Missiles (SAM), radar-controlled guns and shoulder fired SAMs. Before Sunday evening this multilayered umbrella had succeeded in destroying thirty counter-attacking Israeli aircraft. At this rate, the Israeli air force would not last for two weeks of operations.

However, the SAM-‘umbrella’ had its limitations: the Egyptian troops did not want to venture from under it.

The Golan Heights

On the Golan front the surprise was as big as in the Sinai. The Israeli troops held the high ground but they were outnumbered ten to one, in men, tanks and artillery pieces. By a daring helicopter assault on an intelligence outpost on top of Mount Hermon, Syrian commandos beat the Israeli forces in a game the Israelis thought they were masters in.

The Syrians got hold of some American high-tech intelligence equipment, but their aim was more ambitious: throw the two armoured brigades with 180 tanks from the Golan Heights, dig in with their 1300 or so tanks and create a ‘fact on the ground’. For Israel this was the darkest hour of the war. From a general’s viewpoint the Syrian tank army looked on the threshold of entering Israel proper.

It is said that at this point Israeli aircraft and Jericho missiles were loaded with nuclear warheads to avoid or avenge a total collapse. The Syrian tanks did not succeed. The two Israeli armoured brigades took advantage of prepared positions, higher ground and marksmanship in narrowly defeating the Syrian onslaught. They bought time for reserve units to arrive.

In a tactic that was later adopted by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces to stem the threat of a feared massive Soviet tank attack, the available formations were not used to shore up the defences of the most threatened sector, but to attack a weak spot in the attacker’s formations.

Stabilization and New Offensives

After some days the Syrian and Egyptian fronts had stabilized. Everybody pondered what the next round should be. Fierce Israeli counterattacks were inevitable. The Egyptian high command was split whether it should launch an attack from the relative safety of the SAM-umbrella. Syria’s offensive had stalled for the moment, but a second round was in the making.

On the international scene there were also movements. Arab reinforcements, from Morocco, Jordan and Iraq were on their way to the fronts. American and Soviet airlifts began re-supplying Israel and the Arab states in earnest as of 12 October, 1973. Especially Soviet SAMs were in short supply, and Israel could test American low flying, standoff Maverick missiles against the dangerous SAM-batteries.

Halfway through October Egypt’s president Anwar Sadat, against the advice of some of his generals, ordered his military to go on the offensive and occupy a number of passes in the centre of the Sinai. At the same time Israeli forces were on their way to cross the Suez Canal near the Great Bitter Lake. In doing so they could eliminate the SAM-batteries with ground forces and threaten to cut off the Egyptian Third and Second Armies that were lodged on the east bank of the canal.

On 14 October, 1973 Egyptian armoured formations started their offensive from under the SAM-protection. The results were devastating: without air protection their tanks were vulnerable to air interdiction and close air support. The remainder of the Egyptian offensive was defeated by Israeli tank forces. The day before the bulk of the Syrian attacking tank forces had been defeated on the Golan.

Israelis crossing the Suez Canal

Israeli general Ariel Sharon pried open the weak seam between the two Egyptian armies and undertook the long rehearsed crossing of the Canal on 15 October, 1973. At first small-scale forces trickled into Egypt, but within days sizable Israeli forces held a bridgehead on the west side of the canal.

Egyptian counterattacks were fierce but led to nothing. Sharon’s forces succeeded in cutting-off the Third Army and at some point looked to be able to push lightly towards Cairo.

Ceasefire and Mediation

International mediation gathered pace. Both the Soviet-Union and the United States considered a total Israeli victory as less desirable. On October 22, the UNSC passed Resolution 338, in which all parties in the fighting were ordered to cease fire. It furthermore called ‘upon all parties concerned to start immediately after the ceasefire the implementation of Security Council Resolution 242 (1967) in all of its parts’, and for the start of negotiations ‘aimed at establishing a just and durable peace in the Middle East’.

On October 24, when the United Nations brokered ceasefire intended to end the Arab-Israeli War had come into force, further fighting started between Egyptian and Israeli troops. Western intelligence reports concluded that the Soviet Union was planning to send paratroopers to Egypt to protect the Egyptian troops.

At that time, the American President Nixon was in the throes of the Watergate scandal, so foreign affairs secretary Henry Kissinger declared DEFCON 3 – Defence Condition 3, a heightened nuclear alert posture of the American armed forces. This was meant to repel the Soviet Union to take any action and it worked. It avoided further escalation. On October 26, all hostilities ceased.

The outcome of the October War was a victory for Israel. However, achieving initial surprise over the Israelis, who had been thought to be invincible, proved a solid psychological win for the Arabs, no matter what happened after the initial gains.

Attempting to reach a diplomatic agreement, the United States and the Soviet Union invited Israel, Egypt, Jordan and Syria to a peace conference in Geneva (Switzerland), to hold talks on the basis of ‘242’ and ‘338’. Syria declined to participate; the PLO was not invited. The Geneva Conference, chaired by the UN Secretary-General, took place on 21 December 1973.

No concrete results were gained, other than a pledge to set up a military working group, entrusted with the disengagement of the armed forces. Consequently, disengagement agreements were reached between Israel and Egypt (18 January 1974) and between Israel and Syria (31 May 1974).

Israel-Egypt Interim Agreement

In all, after years of stagnation, the near-defeat of Israel, or the near-victory of Arab states, had created a new military and political reality in the Israeli-Arab conflict. This opened the way for renewed diplomacy. Shuttle diplomacy by the American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and secret contacts between Egypt and Israel would bear fruit. Egypt eventually decided to break ranks with the other Arab states and enter into a bilateral deal with Israel in order to regain the Sinai Peninsula, which was still occupied by Israel.

And thus, in the midst of the Cold War, Egypt switched to the American camp, after severing its military and other relations with the Soviet Union.

For Israel, a peace deal with Egypt – its main Arab opponent – was of great importance, since it would neutralize its southern front and deprive its remaining Arab opponents of any (conventional) war option.

On 4 September 1975, both countries signed an Israel-Egypt Interim Agreement, in which further military arrangements were made and in which they declared their intention to reach ‘a final and just peace settlement by means of negotiations [as] called for by Security Council Resolution 338’. On 22 September 1975, this was followed by a second round of disengagement in the Sinai Peninsula.

Sadat’s Trip

On 19 November 1977, Egypt’s president Anwar Sadat surprised friend and foe by travelling to Jerusalem for a two-day visit. He held talks with members of the Israeli government and addressed the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. A month later, on 25/26 December 1977, Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin met in Ismailia (Egypt) to seal the Israeli-Egyptian diplomatic breakthrough.

In the new situation, a planned second round of the multilateral Geneva Conference seemed irrelevant and was cancelled. Yet six years later, at the request of the UNGA, a second UN conference would take place in Geneva (from 23 August-7 September 1983) in which 137 UN member states participated. It was boycotted by the United States and Israel. In its final declaration, the Conference called for a UN peace conference with the full participation of all parties involved, including the PLO (Geneva Declaration on Palestine).

Camp David I

Egyptian President Sadat’s visit to Israel was followed by intensive negotiations a year later (5-17 September 1978). Sadat, Begin, and American President Jimmy Carter met at the presidential retreat in Camp David, Maryland. The result was what came to be known as the Camp David Accords.

The Camp David Accords consisted of two documents. The first document (Israel-Egypt Framework for Peace in the Middle East of 17 September 1978) contained a general framework on the basis of Resolutions 242 and 338 and urged Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and the representatives of the Palestinian people to participate in negotiations concerning ‘the resolution of the Palestinian problem in all its aspects’.

Concretely, the Palestinians were offered a restricted form of autonomy under a Palestinian National Authority for a five-year period, during which they could elect their representatives. After three years, negotiations would commence on eventual sovereignty. The document was completely silent about self-determination for the Palestinians, and Israel offered no commitment to withdrawal from the territories occupied in 1967.

The second document (Peace Treaty Between Israel and Egypt of 26 March 1979) was a detailed peace agreement between Israel and Egypt, providing for a total withdrawal by Israel from the Sinai Peninsula in return for full normalization of the relations between the two countries. The Israel-Egypt peace treaty was eventually signed by Begin and Sadat in Washington on 26 March 1979.

As many in the Arab World and elsewhere predicted, only the second document would be implemented. The negotiations over issues that were outlined in the first document with respect to the position of the Palestinians quickly stalled.

In the following years, successive Israeli governments accelerated the construction in the already existing Israeli settlements in Palestine, and created new ones, including ones close to major Palestinian population centres. In addition, Israel annexed East Jerusalem on 30 July 1980 (UNSC Resolution 478 of 20 August 1980), and the Golan Heights on 14 December 1981 (UNSC Resolution 497 of 17 December 1981).

Recognition of the PLO

The Camp David Accords were a major blow to the political aspirations of the Palestinians, particularly since the PLO had made important gains on the level of international diplomacy after 1969. This was especially the case after the Palestinian National Council (Palestinian National Council 10-Point Political Program) had called for the establishment of an ‘independent combatant national authority for the people over every part of Palestinian territory that is liberated’ on 19 February 1974 and again on 12 June 1974 – thus making some room for a possible division of Palestine.

The PLO Charters of 1964 and 1968, on the other hand, only spoke of a solution for Palestine as a whole. This fundamental change of position would turn out to be a source of tension within the ranks of the PLO. After all, the political position no longer was to insist on the creation of a secular democratic state in the whole of Palestine with equal rights for Palestinians and Jews alike.

Next, in quick succession, came recognition by the United Nations General Assembly of the PLO as ‘the representative of the Palestinian people’ (Resolution 3210 of 14 October 1974) and recognition by the League of Arab States of the PLO as ‘the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people in any Palestinian territory that is liberated’ (League of Arab States Resolution of 28 October 1974). Palestine, as represented by the PLO, obtained full membership of the League of Arab States on 9 September 1976.

On 13 November 1974, PLO chairman Arafat addressed the plenary session of the UNGA, followed by the reaffirmation (UNGA Resolution 2672 of 8 December 1970) by the UNGA of ‘the inalienable rights [of the Palestinian people], in particular its right to self-determination’ (UNGA Resolution 3236 of 22 November 1974) and an UN Observer Status for the PLO ‘in the sessions and the work of the General Assembly’ (UNGA Resolution 3237 of 22 November 1974).

The Lebanon War of 1982

In March 1978, three years after the Civil War in Lebanon broke out, the Israeli army moved into southern Lebanon in an operation against armed PLO units and other groups. Under pressure from the United States and the United Nations, the Israeli Armed Forces withdrew from Lebanon in June. A United Nations peacekeeping force, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), was deployed in the south.

On 4 June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon again in an effort to destroy the PLO infrastructure (which was well-developed to the extent that many Lebanese spoke about ‘a state within a state’). Further objectives were to reduce the political aspirations of the Palestinians in the territories occupied in 1967 and to weaken the position of Syria, present in Lebanon with a military force since 1976. Indeed, the substantial Syrian military presence in the Beqaa Valley presented a significant military factor that had to be taken into account.

In 1981 the Syrian army had closed the ‘gate to Damascus’ with armoured forces under a network of Soviet-type surface-to-air missiles, such as the mobile SA-6 and SA-9.

These sophisticated missiles had cost the Israeli air force dearly during the war of 1973. However, the Israeli forces had worked out a way to counter the threat: by using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), at that time called Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPV).

Electronic Warfare

Unnoticed, these reconnaissance planes kept track of the SAM-batteries, not just their exact location but also the electronic fingerprint of the early warning and fire control radars. This permitted Israeli electronic warfare systems to blind the SAM batteries and neutralise them with airstrikes and long-range artillery. This tactic set a standard and was subsequently copied all over the world. With the protective umbrella thus removed, the Israeli fighter-bombers would have gained air superiority, were it not for the large-scale counterattack mounted by the Syrian air force. However, this move had been anticipated.

Israeli E-2 Hawkeye airborne warning and control aircraft, equipped with a far looking radar and command and control equipment, saw a hundred MiG-21 and MiG-23 interceptors approaching the airspace over the Beqaa Valley. The pilots of these aircraft relied heavily on information provided by ground controllers in Syria.

Many of the communication links between these ground controllers and air-to-air-fighters had been jammed by Israeli electronic warfare equipment. This critically reduced the situational awareness of the Syrians.

The Israeli Hawkeyes on the other hand could vector F-15s and F-16s unhindered towards their handicapped Syrian opponents. Also RPVs flying over Syrian airbases could keep an eye on MiGs on the ground to see if and when they would take off. The result was remarkable: eighty MiGs were destroyed, with no Israeli losses. Fearing annihilation, hundreds of Syrian tanks withdrew from the Beqaa Valley into Syria.

By September most of the Israeli troops had been withdrawn from Lebanese territory. However, the southern part of Lebanon remained as before under Israeli control (the so-called Security Zone) through its SLA-proxy. Around 10,000 Palestinians and Syrians were killed, as well as 18,000 Lebanese. Israeli losses amounted to 675.

Expulsion of the PLO

After a long siege of Beirut, the PLO was forced to evacuate Lebanon at the end of August. (The Palestinian organization would hold office in Tunis, Tunisia, for the next decade.) Israeli forces occupied West Beirut on 16 September 1982, after the assassination of the Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel.

Between September 16-18, Lebanese Phalange militias massacred almost 2,000 Palestinian civilians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila on the outskirts of Beirut which were under Israeli military control. The massacre brought about an international outcry. Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon was forced to resign. Israel would withdraw its forces from Lebanon in June 1985, except for a 15 kilometre wide buffer zone along Lebanon’s southern border.

The pro-Israeli government of Lebanon concluded a Peace Treaty with Israel on 17 May 1983, which was, however, abrogated on 5 March 1984.

During the war in Lebanon, the European Community (at that time nine member states) issued the so-called Venice Declaration of 13 June 1982, in which a comprehensive peace on the basis of Resolutions 242 and 338 was advocated, while at the same time the ‘legitimate rights of the Palestinian people’ and ‘its right to self-determination’ were emphasized. The ongoing construction of Jewish settlements was described as ‘a serious obstacle’ to peace.

The Reagan Plan

The war in Lebanon motivated the President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, to put forward another Middle East plan. The Reagan Plan (made public on 1 September 1982) called for the resumption of the stalled negotiations on Palestinian autonomy. It spoke about ‘the legitimate rights’ of the Palestinian people and about full autonomy of the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (linked to Jordan), yet it also spoke out against the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, as well as against the annexation of these regions by Israel.

According to the plan, the future of the West Bank, of (an undivided) Jerusalem, and of the Gaza Strip should be determined by negotiations. It demanded a freeze on the building activities in the Jewish settlements and an Israeli withdrawal from the territories occupied in 1967, except from strategically important parts. The plan was rejected by Israel’s Likud Government. The reaction from the Palestinians was mixed. They were dissatisfied that there were no explicit references to the right of self-determination of the Palestinians and to the rights of the refugees.

The Fahd Plan

At its summit in Fez (Morocco), the League of Arab States endorsed an eight-point plan that had been presented the year before by Crown prince Fahd of Saudi Arabia. The basic principles of the Fahd Plan of 7 August 1981, were a total withdrawal by Israel from all the territory (West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip, Golan Heights) that it had conquered in 1967, the dismantling of all Jewish settlements there, the reaffirmation of the right of the Palestinian people by Israel, under the leadership of the PLO, to self-determination, respect for the rights of the refugees, including the right of compensation for those who did not wish to return; and, after a transition period and under UN supervision, the establishment of a Palestinian state with (East) Jerusalem as its capital.

Although not stated explicitly, the plan advocated a two-state approach, with formal recognition of Israel by the Arab states. At the time it was generally ignored, but the basic principles of the plan would be reiterated in later initiatives by Saudi Arabia and the League of Arab States (in 2002, and again in 2007).

Intifada

The continuation of the occupation would eventually lead to the outbreak of a popular uprising (intifada in Arabic) of Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, starting on 9 December 1987. It shortly became clear that the harsh methods used by the Israeli army to quash the uprising were ineffectual. On the contrary, a long period of confrontation commenced. As a consequence, the calls – also in the West – for an end to the occupation swelled. Although the uprising was a spontaneous reaction to the occupation, it was soon organized by local leaders. Among them were representatives of a new current in Palestinian politics: the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) and the Islamic Jihad. Both organizations remained, by choice, outside the PLO.

In order to regain control over political developments, the PLO leadership in exile in Tunis took two steps. The first move was the endorsement on 15 November 1988, by the Palestinian National Council of UNSC Resolution 242 and 338, thus formally supporting a two-state approach in future negotiations. At the same time ‘terrorism in all its forms (including state terrorism)’ was rejected. For the United States this finally opened the way to a formal dialogue with the PLO (soon afterwards ties were severed because of the PLO’s pro-Iraqi stand in the Kuwait Crisis).

The second step, on the same day, was the Declaration of Independence of Palestine, solemnly proclaimed by PLO chairman Arafat at the Palestinian National Council meeting in Algiers (Algeria). Although only of a symbolic nature, the objective was clear: the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Both steps were made easier after King Hussein of Jordan, who over the years had lost political influence on the Palestinians concerned, cut Jordan’s legal and administrative ties with the West Bank on 31 July 1988 (only months after the outbreak of the Intifada). Autonomy for the Palestinians in the West Bank in association with Jordan – the long-time preferred option of the Israeli Labour Party – was thus removed from the political agenda.

A plan by Israel’s Likud Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, which offered interim self-rule to the Palestinians, received no international support (Shamir Plan of 14 May 1989) and was soon forgotten. In the so-called Madrid Declaration of 27 June 1989, the European Union (at that time twelve member states) advocated an international peace conference under the auspices of the United Nations, in which the PLO was also to participate. By that time, the role of the UN in this conflict had become completely marginalized, and with it international law as the guiding principle in conflict resolution. The same applied to the Soviet Union, already in an advanced state of disintegration, and to the European Union. On the international scene, the United States was (and is) the dominant player.

The Gulf War

On 2 August 1990, Iraqi air and ground forces invaded neighbouring Kuwait. The United Nations mandated an international coalition, led by the United States, to drive the forces of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait. American President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker succeeded in forming a coalition of 34 nations, including eight Arab countries: Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Syria, and units of the Kuwaiti Armed Forces that had escaped across the border to Saudi Arabia. Jordan, Yemen and the PLO on the other hand politically supported Saddam Hussein.

On 17 January 1991, the coalition commenced with air operations against Iraqi positions in both Kuwait and Iraq, followed on 23 February by a massive ground assault over a very wide front, Operation Desert Storm. A hundred hours later the battle was over. During this so-called Gulf War Iraq launched Scud missiles on targets in both Saudi Arabia and Israel, in an attempt to provoke Israeli retaliation, which could have divided the coalition. Under American pressure, Israel did not retaliate.

History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our coverage of the history of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Fanack’s historical record meticulously chronicles the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in a chronological sequence, encompassing its origins, crises, wars, peace negotiations, and beyond. It is our most exhaustive historical archive.