Reparations for Palestinians - Common to all peace plans for the Middle East is Israel's refusal to admit responsibility for the refugee problem...

Introduction

Common to all peace plans for the Middle East is Israel’s refusal to admit responsibility for the refugee problem or the displacement of the Palestinian population. The human tragedy following the events of 1948 has been included in some talks but without Israeli concession. All agreements are silent on the issue of the return of the Palestinians to their homes and properties. Israel accepts the establishment of an international fund for resolving the resettling of the refugees in Arab host countries. It is prepared to contribute to such a fund, but only if the international community and institutions act as main contributors alongside Israel.

Reparations by States for Wrongful Acts

Palestinians who were either coerced to leave their homes and properties after the beginning of the conflict with Israel or who fled the violence have – besides a right of return – a right to reparations for their material and immaterial losses. Reparation has to be made by the party responsible for their losses, the State of Israel.

The right of the injured to effective remedies for wrongs committed by states was established in the 1920s in customary international law. The leading judgment on this issue was the decision of the Permanent Court of International Justice in the Chorzow Factory Case: ‘It is a principle of international law that the breach of an engagement involves an obligation to make a reparation in an adequate form.’ The duty of states to afford remedies for their misconduct ‘is so widely acknowledged that the right to an effective remedy of violations of human rights may be regarded as forming part of customary international law’. After World War II this right, as an individual right of victims, became increasingly important in international human rights law. The substantive aspect of the right to remedy is based on the general principle of law that the consequences of the committed wrong must be fully remedied.

Many legal instruments have been enacted since the second half of the 20th century confirming this principle. Some of these instruments enumerate a whole range of possible remedies that have to be offered by states responsible for the violation of human rights. It is not intended here to completely cover in detail all international instruments applying to the right of victims to remedies. Only some instruments considered relevant to the issue at hand will be mentioned here.

These instruments demonstrate that the Palestinians have the right primarily to restitution of their homes and properties by Israel. Compensation for these losses may only be substituted for their right to restitution with their consent. Compensation may also be substituted for restitution when restitution is factually or legally impossible and only after a decision by an impartial tribunal.

Legal Instruments

Very relevant is Resolution 56/83 on the ‘Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts’. This resolution was drawn up by the International Law Commission and brought to the attention of governments by the UN General Assembly in 2001. Several articles of the resolution deal with remedies to be implemented by the state that committed the wrongful act. It lists a range of possible remedies. The first of these are cessation of violations and the offering of guarantees of non-repetition (Article 30). These obligations may include the reform or repeal of laws that are responsible for the violations of human rights. Remedies also entail fully repairing the injuries caused by the internationally wrongful act that has been committed. The injury includes any damage, whether material or moral, caused by this act (Article 31).

The second chapter of the resolution works out the diverse forms of remedies for injuries. These are ‘restitution, compensation and satisfaction, either singly or in combination’. The obligation of states to pay for reparations and the kind of reparations which have to be offered are also confirmed in the General Comment 31 of the Human Rights Committee where an interpretation is given in Article 2, paragraph 3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). In paragraph 16 of the General Comment the Committee observes the following: ‘Article 2, paragraph 3, requires that State Parties make reparation to individuals whose Covenant rights have been violated. Without reparation (…), the obligation to provide an effective remedy, which is central to the efficacy of article 2, paragraph 3 [of the covenant], is not discharged.

In addition to the explicit reparation required by articles 9, paragraph 5 and 14, paragraph 6, the Committee considers that the Covenant generally entails appropriate compensation. The Committee notes that, where appropriate, reparation can involve restitution, rehabilitation and measures of satisfaction, such as public apologies, public memorials, guarantees of non-repetition and changes in relevant laws and practices, as well as bringing to justice the perpetrators of human rights violations.’ These obligations apply to Israel, which ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1991.

European Court of Human Rights

Israel is not a European country and therefore not party to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that the ECHR recognized the right to compensation for the denial of land use and access to property in the Loizidou v. Turkey case. The court required compensation not only for financial losses resulting from a denial of access, but also non-pecuniary damage for what it termed ‘the anguish and feelings of helplessness and frustration which the applicant must have experienced over the years from not being able to use her property as she saw fit’. The court awarded damages on these grounds to Mrs. Loizidou, even though the property in question had not been used as her abode.

Guidelines

The most recent instrument of international law dealing with remedies for victims following wrongful acts by states is the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law (2005) (hereafter Guidelines). The Guidelines ‘do not entail new international or domestic obligations but identify mechanisms, modalities, procedures and methods for the implementation of existing legal obligations under international human rights law and international humanitarian law’.

The Guidelines are restricted to gross violations. They contain a codification of the legal consequences and standards arising from gross violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) constitutes a reference point, since it describes in detail the elements and acts which constitute war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity under international law. In part 2 of the Rome Statute of the ICC on Jurisdiction, Admissibility, and Applicable Law, the crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC are listed in Articles 5 to 8. In accordance with the Rome Statute, the Court has jurisdiction with respect to, among other matters, crimes against humanity and war crimes (Article 5, par. 1 under b and c).

For the purpose of the Statute, ‘crimes against humanity’ include ‘deportation or forcible transfer of population’ and ‘persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity on religious, cultural, political and ethnic grounds (Article 7, par. 1 under d, h). In paragraph 2a, there is a description of the crimes cited in paragraph 1. On deportation it reads: ‘Deportation or forcible transfer of population means forced displacement of the persons concerned by expulsion or other coercive acts from the area in which they are lawfully present, without grounds permitted under international law.’ An explanation is also given of the crime of apartheid and persecution.

Palestinians have been victims of deportation and forcible transfer since the creation of the State of Israel. These acts are still being carried out. In accordance with international law, the Guidelines contain principles allowing the provision of full and effective reparation to victims that are appropriate and proportional to the gravity of the violation and the circumstances of each case.

Basic Ideas

A basic idea of the Guidelines is that reparative justice is a condition for reconciliation, peace and democracy. The reparations described in the Guidelines refer to a wide range of remedies. Some of these have already been enumerated in the above-mentioned instruments:

Restitution which must help the victim to return to the original situation before the violation occurred. Restitution includes, among other things, restoration of liberty, identity, family life, return to one’s place of residence and return of property.

Compensation for any economically assessable damage resulting from physical or mental harm, lost opportunities, material damage and loss of earnings and moral damage. ‘The payment of compensation can be conceived of covering all the damage which the victim has suffered that can be financially assessed so as to ensure full reparation.’

Rehabilitation, including medical and psychological care.

Satisfaction, including a whole list of measures depending on the circumstances, such as official declarations or judicial decisions restoring the dignity, reputation and the rights of the victim, a public apology and acknowledgement of the facts and acceptance of responsibility. ‘Satisfaction’ covers a wide and varied range of non-monetary measures that may contribute to reparation. ‘A central component is the role of public acknowledgment of the violation. (…) Satisfaction may consist of an acknowledgment of the breach, an expression of regret, a formal apology, a declaratory judgement or another appropriate modality. (…) One of the most common forms of satisfaction is a declaration of the wrongfulness of the act by a competent state body, be it a court or a tribunal or some other official organ.’

Guarantees of non-repetition. The Guidelines emphasize the importance of holding to account those who perpetrate human rights abuses: ‘Holding perpetrators legally accountable for their actions is also of great relevance for reparation and is a fundamental way of providing some measure of redress for victims and their families.’

Right to Return as Primary Remedy

The expulsion of a population is considered illegal in a number of international instruments including Article 9 and 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), Article 4 of the Fourth Protocol of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), and the international instruments mentioned under Guidelines. It is considered a crime against humanity in the Rome Statute. Underlying principle is the assignment of rights to individuals, thereby limiting the rights of states to make agreements that adversely affect individuals. The right of displaced persons to return to their country of origin if they have been forcibly expelled is included in the obligations laid down in several provisions of the four Geneva conventions of 1949. It is also one of the bases of refugee law. This right is a consequence of the illegality of the expulsion itself.

Restitution of property is mentioned in many peace agreements as a means to settling conflicts. It suffices here to mention Resolution 361 of the United Nations Security Council, which called on Cyprus to permit people to return to their homes. In August 2005, the United Nations endorsed the Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, the so-called Pinheiro Principles. States are recommended in Principle 1 to prioritize the right to restitution of property as the preferred remedy for displacement and as a key element of restorative justice. Compensation can only be substituted for restitution when restoring housing and property is factually or legally impossible. The decision thereto must be taken by an independent and impartial tribunal and not by the state that is responsible for the losses of the injured (Principle 2).

The Expulsion of Palestinians from their Land

Mandate Palestine was cleansed of four-fifths of its non-Jewish Palestinian population by armed Zionist groups in order to create a Jewish state. The expulsion as well as the refusal of the Israeli government to allow Palestinians to return to their homes and properties is a breach of international law and is defined as a crime against humanity in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Article 7). Through a combination of force and law, Palestinians were dispossessed of their property that lay inside the actual State of Israel after 1948. One group of laws and regulations relevant here concerns the seizure of Palestinian property; the other is the Israeli law of nationality, or law of return.

Seizure of Palestinian Property

Palestinian property seizure began even before 1948 (proclamation of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948). This laid the basis for the legal transfer of Arab land to Israeli institutions. In the first years after its creation the Israeli government tried to legitimize the land seizure retroactively through legislation that allowed only Jews to own land or to benefit from land.

Even before the creation of the state in 1948, attempts had been made to seize Palestinian land by several actors including the Jewish Agency, the precursor of the Israeli army (the Haganah) and individual Jews. In June 1948, the first Abandoned Property Ordinance (Ordinance No. 12, 5708/1948) was enacted as a legal instrument regarding the confiscation of refugees’ land, and in July the first custodian of abandoned property was appointed. Ordinance and regulations have since been revised repeatedly. The enacted laws gave a legal basis to the confiscation. Legislative reforms were used to allow the selling of land mainly to the Jewish National Fund (JNF), and to legitimize retroactively ad hoc seizure of land. These laws did not incorporate explicitly discriminating provisions and appeared neutral with regard to religion and ethnicity. Nevertheless, they contained clauses benefitting the Jewish population of Israel as well as Jews from all over the world. In Israel today, licenses to use the land are granted on exclusively ethnic grounds; Arab citizens are totally excluded from the allocation of public land.

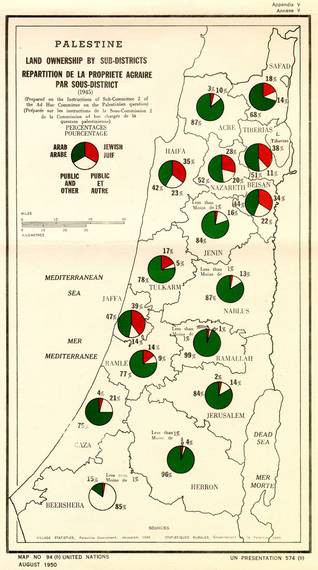

Well over 700,000 Palestinians, 83 percent of the native Palestinian population, were either expelled from their homeland by Jewish armed groups or fled the violence to other parts of Palestine or to neighbouring countries. Of the 140,000 Palestinians who remained, 30,000 became internally displaced persons (IDPs). As a result, the new State of Israel had a solid Jewish majority of around 85 percent in 1949. The expelled Palestinians left behind substantial immovable and non-immovable property. The immovable property has been seized, mostly through the mechanism of the Custodian of Absentee Property. The United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP), created by the UN in 1948, estimated that 80 percent of the territory of Israel as defined by the 1949 armistice was in fact owned by Palestinians and a small minority of Arabs of other origins. Jewish individuals and institutions owned 8.5 percent of the total area of the new state at the most, and approximately 4 percent was owned by the British Mandate. The legal regime enacted by Israel enabled the state to transform property previously owned by Palestinians into Israeli land managed almost exclusively for the benefit of Jews.

The Israeli Law of Nationality

Palestinians who were evicted from Palestine in 1948 were in possession of Palestinian citizenship that was acquired through the British mandatory authority. If Israel were to have acted in conformity with international law, Israeli citizenship should have been granted all Palestinians originating from regions that came under Israeli rule following the change of sovereignty in Palestine. Israeli citizenship should have been given to Palestinians regardless of whether they were physically present when the change of sovereignty occurred. In 1952, the Israeli Nationality Law declared that former Palestinian citizens of Arab origin were eligible for Israeli nationality if they met certain conditions. These conditions were difficult to fulfil, excluding all Palestinians who were displaced or expelled before the War of 1948 from obtaining Israeli citizenship. Displaced Palestinians have subsequently been prevented from returning to their homes. The Israeli Law of Return granted ‘[e]very Jew’ the right to immigrate to the new state as an oleh (immigrant) and to obtain citizenship automatically. This right is denied to those who are not Jewish, even if they have been living in the country for a long period of time.

Valuing Lost Palestinian Property

In 1949, at the same time as the issuing of Resolution 194 by the United Nations General Assembly, the United Nations created the Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP). The primary mandate of the UNCCP was to mediate and seek reconciliation between the conflicting parties after the Arab-Israel War of 1948. The UNCCP’s first major initiative in this direction was to hold a conference in Lausanne (Switzerland) from 27 April to 12 September 1949. Among the issues discussed during the conference were territorial questions, the establishment of recognized borders, the question of Jerusalem, the repatriation of refugees, and the organization of compensation for those who had not been repatriated on the basis of Resolution 194 (III).

During the conference, Israel presented counterclaims to its obligations under Resolution 194. The UNCCP did not succeed in its reconciliation mission. The Lausanne Protocol, which was signed by both parties and which provides a framework for a comprehensive peace, including the issues of territories, refugees and Jerusalem, immediately led to disagreement after signing in regard to its method of implementation. Subsequently, the UNCCP concentrated on attempts to alleviate some consequences of the Israeli-Arab War and tried to effect compensation for the 726,000 Palestinians who had lost their homes and property during 1947-1948.

To this end a Technical Committee was created to investigate practical ways of resolving refugee issues. At the same time the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East (the Clapp Mission) was established to explore economic solutions to the refugee problem. A valuation of the Palestinian properties was therefore needed.

Information Withheld

In 1951, a land expert carried out a quick and general estimate of the refugees‘ property losses that was based on land and property maps and on reports established under the Mandate. This so-called ‘global estimate’ was followed in 1952 by a more detailed study based, among other things, on land taxation records. The project was terminated in 1964. Professor of History at Randolph-Macon College (Ashland, United States), Michael Fischbach wrote: ‘The purpose was to determine, first, the exact amount of all individually-owned Arab land as of 14 May 1948 that lay in the part of British Palestine that became Israel. Beyond that, the Technical Project also sought to determine the value of this property, in Palestinian pounds, as of 29 November 1947.’

In a comprehensive research on the work of the UNCCP, Fischbach reported that the UNCCP did not release all the details of the study but only what the author calls a ‘sanitized’ report of its final estimate of Palestinian and Arab land in Israel in April 1964. Many details of the study, particularly on the value of the land, were not made public until the beginning of the 21st century. It was only with special permission that access was granted to view this information, which was held under lock and key at the UN Secretariat Archives in New York for decades. Filmed copies of these archives were sold to several Arab parties in the 1970s and 1980s.

According to Fischbach, who was allowed to conduct research on the material in New York, the archives contain a huge number of paper and filmed records. The paper material consists of documents and ‘forms which have been developed by the UNCCP to record the details of specific parcels of Arab property in Israel’ and of ‘several thousand maps, largely mandatory maps of Palestinian villages’. The films – 226 rolls of 16mm – consist of filmed copies with an owner’s index as well as hundreds of rolls of Ottoman and British mandatory land registers that the British government sold to the UNCCP in 1952. It goes without saying that the material is of tremendous importance to the question of restitution and compensation to Palestinian refugees.

The UNCCP’s study included other factors besides the value of Arab property in its overall plan to compensate Palestinian refugees, such as changes in the value of the currency, the value of moveable property, a ‘disturbance allowance’ representing the loss of a refugee’s income until re-establishment, and an ex-gratia payment constituting general compensation for hardship.

Other Studies

Arab economists challenged the estimates of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) and criticized it for neglecting or giving insufficient value to critical issues such as human suffering, loss of capital and public property. In 1955, the UNCCP study was supplemented by another study carried out by the Arab Higher Committee and published in Cairo under the title Palestinian Refugees: Victims of Imperialism and Zionism. In 1961, the study was also published in Beirut under the title Statement. The estimates in this study are twenty times (therefore substantially) higher than those of the UNCCP and include non-real estate assets such as jewellery and livestock. In 1964, a third study on compensation to Palestinian refugees was published by the Palestinian economist Yusuf Sayegh, with the title The Israeli Economy. In this study, many of the factors omitted in the two former studies were considered and assessed in conformity with economic principles.

Sami Hadawi, in charge of the land taxation department of Palestine during the British Mandate period, worked as a ‘land specialist’ for the UNCCP in New York after the termination of the Mandate and the fall of Palestine. At the UNCCP, he was entrusted with the task of identifying and assessing Palestinian land property in the territories of Palestine that Israel had occupied. In 1959, Hadawi joined the Arab Information Centre of the Arab League; in 1965 he became director of the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut. Hadawi also conducted a study titled Palestinian Rights and Losses in 1948 in 1988. The various studies demonstrate that the outcome of the final sum of valuation, depending on the criteria involved, is huge, amounting to at least 63 billion USD.

Israel’s Response to the Right of Compensation

United Nations Resolution 194 states that compensation should be paid for loss of or damage to the property of those Palestinians who choose not to return to their homes. Since Israel categorically refuses restitution of property, which entails the Palestinian right of return, it could have considered the Palestinian right to compensation for their losses. Israel could have applied the principles established by the International Law Association ‘in order to facilitate compensation, as appropriate to persons who have been forced to leave their homes in their homelands and are unable to return to them’. To admit the right of compensation of refugees is considered crucial for the development of peaceful and friendly relations between former enemies.

In the case of the German compensation after the war to Jewish refugees and to the State of Israel, ‘such compensation has served to heal historical wounds, transforming a relationship marked by hostility between Germans and Jews into one of reconciliation’. This reasoning also applies to the conflict between Israel and Palestinian refugees. Since its creation, Israel has followed not only a policy of refusal of repatriation of Palestinian refugees as required by Resolution 194 (III) but also a refusal to compensate them for their losses. Giving compensation to Palestinians implies accepting moral responsibility for what happened to them, and this has consequently been denied by Israel.

The opinion of former Israeli general Shlomo Gazit is that ‘an inverse correlation will continue to exist between the financial and normative admission of guilt components of possible Israeli compensation. In other words, the less compensation looks like reparations, the more likely Israel may be willing to offer “funds” which can be used to help in resettling Palestinian refugees in the actual host countries’.

Israeli historian Ilan Pappé shares Gazit’s analysis and believes that Israel developed a strong mechanism of denial of the 1948 events, not only for pragmatic reasons ‘but far more importantly so as to thwart all significant debate on the essence and moral foundations of Zionism. (…) It calls into question the very foundational myths of the State of Israel and it raises a host of ethical questions that have inescapable implications for the future of the State.’

For most Palestinians, to reach a solution to the conflict without Israel admitting its responsibility for the refugee problem is unacceptable. Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi emphasizes firstly that real healing and reconciliation is only possible when the victims are recognized as such and the perpetrators accept their responsibility for the wrong they have committed. This standpoint is widely accepted in regard to other conflicts that have occurred in the 20th century.

Secondly, he considers the admission of responsibility as necessary since most refugees or their descendants will never be allowed to exercise their right of return to their original homes in what is now Israel. It is essential therefore that the ‘existential hurt that was done to the majority of the Palestinian people be acknowledged by those who did that hurt or their successors in power’. Khalidi has termed this acknowledgement a symbolic response; a response that is all the more important because fundamental redress cannot be expected, excepting compensation.

Human Rights & Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our Human Rights & International Law coverage within the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

The Human Rights & International Law dossier on the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict meticulously documents the conflict, covering a wide range of topics, including treaties, human rights violations, policies that contravene international law, and more.