Acclaimed academics at Fanack explore the unfolding of the Arab-Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the Oslo Accords.

Collapse of the Oslo Accords

As in the case of Resolutions 242 and 338, ‘Oslo’ was not based on international law. The negotiating track was vague, as was the ultimate goal (although not for the Palestinians who wanted to establish an independent, viable state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip – the remaining 22 percent of historical Palestine – with East Jerusalem as its capital, and a just solution for the Palestinian refugees). Under these circumstances, the strongest party was in the position to impose its interpretation of the basic accords. In order to fill the gaps, a detailed proposal was formulated in informal negotiations between Mahmoud Abbas and Yosef (Yossi) Beilin (Beilin-Abu Mazen Document of 31 October 1995).

Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty

For Jordan, the Oslo Process had removed the last obstacle to striking a peace deal with Israel. In the 1980s, both countries had already reached agreement about the procedures (London Agreement of 11 April 1987). On 14 September 1993 – one day after the signing of the Declaration of Principles – the Israel-Jordan Common Agenda was announced.

Finally, and in the presence of President Clinton, the Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty was signed in the Arava Valley/Wadi Araba (Israel) on 26 October 1994, close to the border with Jordan (see also The Washington Declaration of 25 July 1994).

Israeli-Syrian Negotiations

With Syria, all negotiations since ‘Madrid’ have foundered, American mediation attempts notwithstanding (the meeting between President Clinton and Syrian President Hafiz al-Assad on 16 January 1994 in Geneva; Clinton’s visit to Damascus on 27 October 1994; three rounds of Israeli-Syrian talks in Wye River (Maryland) between 27 December 1995 and 3 March 1996; talks in Washington on 15-16 December 2000; talks in Shepherdstown (West Virginia) from 3-17 January 2000; and finally the Clinton-al-Assad meeting in Geneva on 26 March 2001).

In these talks Syria demanded, in return for a peace agreement, total Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights (including the dismantling of the 35 Jewish settlements there). Israel, for its part, proposed a phased retreat that would be dependent on the steps taken by Syria with respect to normalization of the relations between the two countries. Israel insisted on keeping complete control over the Syrian part of the shore of the Lake Tiberias (Lake Kinneret), thereby obtaining de jure control over the lake, and posed conditions with regard to the future status of the Golan Heights (demilitarized area, nature reserve). To Syria these conditions were – and still are – unacceptable. In 2008, Turkey facilitated indirect Israeli-Syrian talks, which were suspended after Israel’s large-scale attack on the Gaza Strip in December of that year. Given Syria’s strong influence in Lebanon, no peace agreement between Israel and Lebanon has been reached since ‘Madrid’ either.

On 24 May 2000, under the pressure of armed resistance by Hezbollah and other organizations, Israel withdrew unilaterally from Lebanese territory which it had occupied since its first invasion in March 1978 (UNSC-Resolution 425 of 19 March 1978).

Wye River

Little progress was made on the Israeli-Palestinian track. Construction in the Jewish settlements continued at an accelerated pace, resulting in a strong growth of settlements in terms of size and number of settlers during the five-year Interim Phase. The army of Israel in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip regrouped but did not withdrew. The economic situation deteriorated, and political tensions began to run high again. This resulted in an escalation of violence (shootings, suicide attacks, extrajudicial killings). Soon, intervention by the United States became necessary to prevent a collapse of the Oslo process (the Hebron Protocol of 15 January 1997, and the Wye River Memorandum of 23 October 1998).

The Palestinian National Council had by that time already removed the last formal obstacles to an agreement, such as a revision of its Charter, revoking all its anti-Israel articles (Palestine National Charter, revised, of 26 April 1996, and the Arafat-Clinton Letter of 13 January 1998). After the Interim Phase had formally expired on 4 May 1999, the demand by Israel’s Prime Minister Ehud Barak (Labour) to start final status negotiations (Sharm el-Sheikh Memorandum of 4 September 1999) did not break through the stalemate.

Camp David-II

From 11-25 July 2000, in a last effort to reach a comprehensive deal before leaving office, President Clinton organized a summit meeting in Camp David between Barak and Arafat. The negotiations – ill-prepared and under pressure – again failed to produce results, because the maximum Israel had to offer (again) did not meet the minimum the Palestinians demanded (Joint Statement Clinton-Barak of 19 July 1999, and Trilateral Statement Camp David Summit of July 25, 2000). In retrospect, experts and persons involved in the negotiations agree that Arafat undeservedly received all the blame for the failure of the talks.

Informal talks in Taba (Egypt) from 18-28 January 2001, on the basis of the Clinton Parameters the results of which were documented by EU Special Representative Miguel Moratinos, came too late to have an effect, especially since from 28 September 2000 another Intifada had been raging through the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, leading to an escalation of violence. By that time, an increasing number of Palestinians had already raised big question marks with respect to the political strategy of the PLO/PNA in the Oslo-process. As a result, Hamas – a strong opponent of ‘Oslo’ from the start – gained political support.

Withdrawal from Gaza

To free itself from the direct control of a large number of Palestinians and to strengthen its grip on the West Bank, the Likud Government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon decided to disengage unilaterally from the Gaza Strip (Sharon’s Unilateral Disengagement Plan of January 2005).

On August 15, Sharon said that although he had hoped Israel could keep the Gaza settlements, reality demanded otherwise: ‘It is out of strength and not weakness that we are taking this step’ he was quoted as saying. Israel’s motives to retreat unilaterally from the Gaza Strip were announced in a communication by the Prime Minister’s office. According to the communication Israel had no reliable Palestinian partner to negotiate with and it believed that a retreat from Gaza would lead to a better security situation. On the other hand the retreat also meant that the towns and villages in the West Bank would remain part of Israel.

The Israeli withdrawal that followed took place in August 2005. Despite the withdrawal, Israel continued to exercise direct control over the Gaza Strip. Under international law, Israel therefore remained the occupying power.

The Wall

In 2004, the International Court of Justice in The Hague in its advisory opinion (ICJ Advisory Opinion of 9 July 2004) qualified the construction in the West Bank of Israel’s separation barrier (Wall) outside the so-called Green Line as a violation of international law. That part of the Wall should be dismantled and compensation should be paid to Palestinians for any damage inflicted. Moreover, the ICJ declared Israel’s settlements illegal.

The next month, with an overwhelming majority (150 to 6, with 10 abstentions), the UNGA passed a resolution in which Israel, ‘the occupying power’, was called upon to ‘comply with its legal obligations as mentioned in the advisory opinion’ (UNGA Resolution ICJ-Wall of 2 August 2004). To the present day, Israel has not complied. The construction of the Wall has continued at an accelerated pace.

Annapolis

A few months before the ICJ ruling on the Wall, President George W. Bush had written to Prime Minister Sharon and suggested that the United States would accept Israel keeping some of the settlements: ‘In light of new realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli population centres [Jewish settlements], it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949’ (Bush-Sharon Letters of 14 April 2004). In November 2007, with the end of his presidency in sight, Bush organized a summit in Annapolis (Maryland) to breathe new life into the Road Map. Besides Israel and the PLO/PNA, the main Arab states attended the meeting. The result was a pledge to reach agreement over major issues before the end of 2008 (Annapolis Conference of 27 November 2007). A series of secret negotiations followed, however without achieving any tangible results. In January 2011, the contents of the negotiations were leaked and made public as the ‘Palestine Papers’.

Internal Palestinian Split

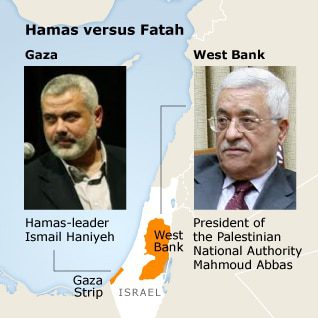

In the second elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), in January 2006, Hamas, won with 44.5 percent of the vote, giving them a total of 74 seats in the 132-seat Council, of which 29 seats were won according to the system of proportional representation and no less than 45 were in constituencies. Fatah, until then the most important political force among Palestinians, reaped with 41.4 percent of the vote and 45 seats: 25 under the proportional system and 17 in the constituencies. In the elections, Ismail Haniyeh had led the campaign of Hamas under the slogan ‘Change and Reform’. He was appointed Prime Minister by President Mahmoud Abbas and sworn in on 29 March 2006. On 14 June 2007, Abbas dismissed Haniyeh at the height of internal clashes in Gaza between armed forces of Hamas and Fatah, which lead to the complete takeover of power in the Gaza Strip by Hamas. This sharp conflict brought about paralysis of the functioning of the Palestine institutions. Abbas appointed Salam Fayyad Prime Minister, previously the Minister of Finance. However, the PLC, with its Hamas majority, did not approve this appointment and still recognized Haniyeh as Prime Minister.

Due to the conflict the sessions of the PLC and new elections for the Presidency (due in 2009) and the PLC (in 2010) seemed to be on a hold indefinitely and the internal Palestinian split complicated further the negotiations with Israel which by that time had already come to an almost complete standstill.

History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our coverage of the history of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Fanack’s historical record meticulously chronicles the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in a chronological sequence, encompassing its origins, crises, wars, peace negotiations, and beyond. It is our most exhaustive historical archive.