The unfolding and the effect of the Suez Crisis in 1956 and the June War in 1967

The Suez Crisis of 1956

In May 1956, the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser recognized the People’s Republic of China, thereby angering the United States. In response, on 19 July 1956 Washington decided to withdraw its financial aid for the realization of a large irrigation project in Egypt, the High Dam at Aswan. One week later, on 26 July 1956, Nasser announced the nationalization of the British-French owned Suez Canal Company, thereby obstructing Great Britain and France’s interests. Outright military intervention was not an option however, since it lacked diplomatic backing from the United States.

So the British and French governments turned to Israel, which was looking for ways to stop attacks by Palestinian fedayeen (guerrilla fighters) from the Gaza Strip (since 1948 under the control of Egypt). The three parties signed a secret agreement, known as the Protocol of Sèvres, according to which Israel would attack the Gaza Strip to neutralize fedayeen and lure the Egyptian army into retaliating. Then, the Israeli army would quickly invade the Sinai, a perfect excuse for the British and French governments to intervene with a ‘peace enforcing’ mission. In the process the British and French forces would reclaim authority over the Canal.

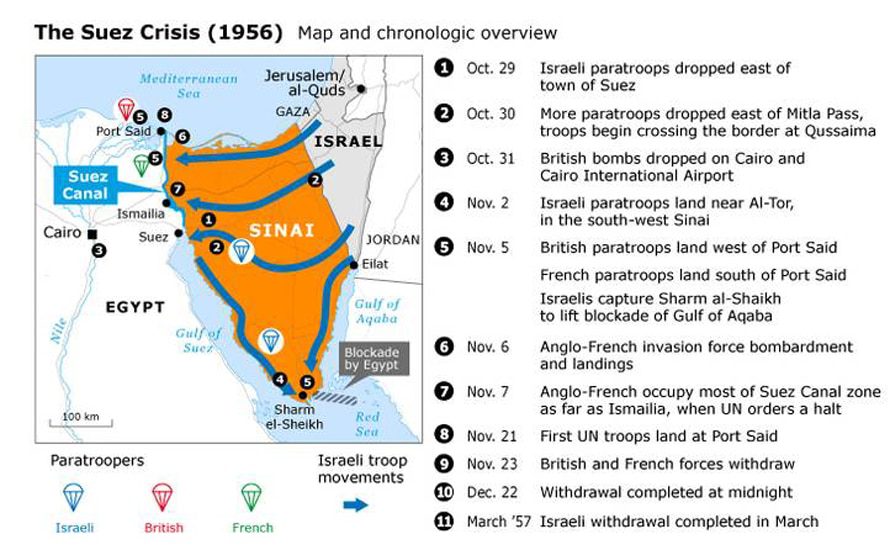

On 29 October 1956, Israeli paratroopers dropped east of Suez at the southern entrance of the waterway. The next day, after more paratroopers had secured more important passes in the ‘hinterland’ of the Egyptian army in the Sinai, the Israeli army crossed into the northern part of the desert. The Israeli Air Force could pit the recently acquired French Mystère fighters against the new MiG-15 in air battles over the Sinai. Air superiority was soon established.

On 5 November 1956, British and French forces started their intervention with airborne landings near Port Said. On the same day Israeli forces stopped near the Canal Zone and, in the south of the peninsula, occupied Sharm el-Sheikh and lifted the blockade of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Under pressure from both the United States and the General Assembly of the United Nations, the three forces withdrew and a ceasefire was concluded on 6 November 1956. A UN Emergency Force (UNEF), the first peacekeeping force in the history of the UN, was placed between the warring sides. The Israeli forces left the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip in March 1957. UNEF left the Sinai in May/June 1967 on the request of Egypt, shortly before the outbreak of the June War.

The presence of UN troops offered Israel increased security – the decade after the war was the most tranquil period in the nation’s history. It also obtained guarantees from the United States that the Suez Canal, as an international waterway, would remain open to Israeli shipping.

The June War of 1967

One of the major developments – with hindsight – in the relations between Israel and its Arab neighbours, was the June War of 1967.

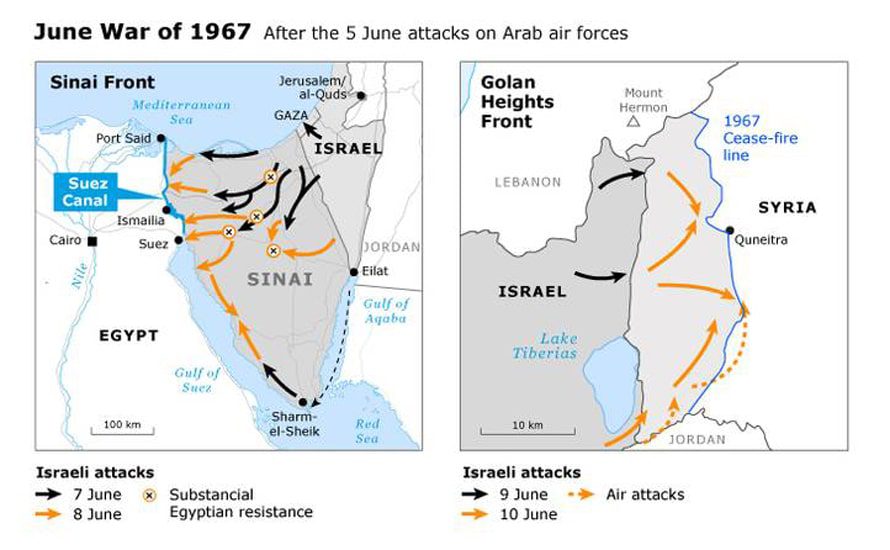

The outcome of the war that raged from the 5th to the 10th of June 1967 was as stunning a victory for Israel as they would get. It took the Israeli armed forces only four days to evict the larger Egyptian army from the Sinai, two and a half days to defeat the Jordanian army on the West Bank, and a day and a half to wrestle the Golan Heights from the Syrian armed forces. This was after an Israeli aerial blitz, Operation Moked, had destroyed most of the air forces of these countries.

The hostilities started after the rhetoric had been heating up for months, culminating on 18 May 1967 in the expulsion by the Egyptian president Nasser of the peace keeping force of United Nations’ ‘blue-helmets‘ from the Sinai.

He also closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. Egyptian, Syrian and Jordanian forces were mobilized. The Israeli military leadership saw a long awaited chance to change the balance of forces in Israel’s advantage. They had become convinced they could defeat the opposing Arab armed forces, provided they started hostilities with a surprise attack on the Egyptian air force.

Disruptive innovation

On 5 June the Israeli air force of some 230 mainly French combat aircraft displayed what one would nowadays call tactical ‘disruptive innovation’. Thorough intelligence had revealed the alert procedures of the opposing Arab air forces. When Arab, Soviet-made, early warning radars observed approaching aircraft, their MiGs and Sukhois on alert status left their hangars and started take-off procedures. These aircraft stayed on the tarmac for some time, warming up the engines and checking avionics and other systems.

The Israeli aircraft, practically the whole inventory, flew under the radar and had timed their appearance on the radar screens so that they would be on top of the taxiing Arab fighters before they could take off. The trick worked.

Israeli heat seeking missiles and guns destroyed hundreds of aircraft, ranging from top-of-the-line MiG 21 air-superiority fighters to heavy Badger bombers, helicopters and transport planes – at a cost of only 19 aircraft on the Israeli side. The Arab air forces were numerically superior, and the Soviet equipment could also be considered more modern than the relatively old French equipment the Israeli air force had in its inventory.

The subsequent defeat of the Arab armies had as much to do with Israeli training, tactics and doctrine as with military incompetence. The Egyptian army, for example, was organized in the same manner as the French army in 1940: small armoured detachments were linked to infantry divisions that were positioned on the border with Israel, thus lacking depth. The ‘masse de manoeuvre’ consisted of a meagre armoured force.

In the night of the first day of the war Israeli formations, with the deployment of paratroopers to provide deep penetration, attacked the Egyptian fortifications in the desert. A counter-attack came to nothing. Retreating Egyptian troops were surprised by Israeli armour that had overtaken them. After the Egyptian army had been defeated, Israeli troops fanned out over the Sinai Peninsula and dug in.

The Syrian Defeat

The Syrian front started to heat up later on 5 June. Here too, Israeli aircraft destroyed the bulk of the Syrian aircraft on the ground. The Syrian tactics were not effective: a few tanks rumbled into Israeli territory and artillery shells rained down from the Golan Heights on villages and farms below.

After two days of debate the Israeli generals decided that the chaos within the ranks of their Arab counterparts resulting from the battering they had received, presented a window of opportunity to take the fortified heights. In the end, the poorly trained Syrian defenders proved inadequate to resist the Israeli formations. They fled in chaos.

The Jordanian Defeat

The scenes on the West Bank, on which the bulk of the Jordan armed forces were positioned, were no different from those in the Sinai and on the Golan Heights. Although much better trained and disciplined than the Syrian and Egyptian forces, the Jordanian army proved no match for Israeli armoured tactics and the rapid operations by paratroopers.

On 10 June, a ceasefire was brokered by the United Nations. With the crushing defeat of the armed forces of three neighbouring countries, the June War drastically changed the balance of power, to Israel’s advantage.

Results of the 1967 War

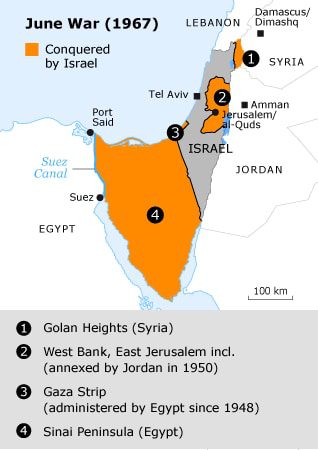

In the course of the war, the last remnants of the former Mandate of Palestine were conquered by Israel: the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. In addition, Israel took control of the Sinai Peninsula (from Egypt) and the Golan Heights (from Syria).The shock that the defeat brought about in the Arab World was enormous.

Deep feelings of humiliation help to explain why on 1 September 1967, at the following summit of the League of Arab States in Khartoum (Sudan), a resolution was passed (Khartoum Resolutions) in which the member states declared three No’s: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel (besides a common political and diplomatic effort to force Israel to withdraw from recently conquered Arab territory, and support for the rights of the Palestinian people).

The shock that the defeat brought about in the Arab World was enormous. Deep feelings of humiliation help to explain why on 1 September 1967, at the following summit of the League of Arab States in Khartoum (Sudan), a resolution was passed (Khartoum Resolutions) in which the member states declared three No’s: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel (besides a common political and diplomatic effort to force Israel to withdraw from recently conquered Arab territory, and support for the rights of the Palestinian people).

Thus, the military results of the June War may indeed have been spectacular, but they did not lower the tensions in the region.

Furthermore, the June War would ultimately (on 3 February 1969) lead to a takeover of the PLO from within by the Palestinian member organizations, which had lost confidence in the policies of the Arab states with regard to Israel. As a result, the PLO could now be regarded as the true representative of the Palestinian people.

Fatah leader Yasser Arafat became its new chairman. As early as 17 July 1968 – in the wake of the June War – the PLO had amended its 1964 Charter, presenting the rights of the Palestinian people in more explicit terms (Palestine National Charter 1968).

During the crisis, public opinion in the West had been solidly behind Israel. Because of its quick and devastating victory, Israel came to be seen by the United States as a great military/strategic asset. The increasing military co-operation after 1967 would ultimately – in November 1981 – result in a USA-Israel strategic cooperation agreement.

Thus the Middle East became, more than ever before, one of the battlefields of the Cold War, with the United States and other Western powers supporting Israel, and the Arab states seeking military and diplomatic support from the Soviet block.

Israel now formulated its plans with respect to the newly conquered territory, first and foremost the West Bank (the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights were seen by many – but not all – Israeli politicians as bargaining chips in future peace agreements with Egypt and Syria respectively).

On the basis of the Allon Plan of 26 July 1967, named after its architect, former general and cabinet member Yigal Allon, Israel aimed at annexing the Jordan Valley (the border with Jordan) and a large area around East Jerusalem, as well as a land corridor to connect both. The southern part of Gaza Strip would also stay under Israeli control.

In order to strengthen its grip on these areas, Israel started to build a series of Israeli settlements (in addition to military bases). The plan offered the Palestinian inhabitants in the remaining parts of the West Bank (the main population centres) a form of limited self-government in association with Jordan (which had governed the West Bank between 1948 and 1967).

Resolution 242

It took the UN Security Council several months to reach an agreement over the content and the exact wording of a resolution addressing the new situation. The final result was UNSC Resolution 242 of November 22, 1967. The significance of this resolution should not be underestimated. Most UN resolutions dealing with the Israeli-Arab-Palestinian conflict refer in their preambles to ‘242’.

In its introduction, Resolution 242 emphasizes – in line with the UN Charter – ‘the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war’ and demands ‘withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict’.

In return it demands ‘termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every state in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force’. Finally it affirms the necessity ‘for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem’.

Resolution 242 was conceived within the logic of a negotiated settlement between states. Non-state entities, like the (stateless) Palestinian people, fell outside this logic. The Palestinians were only indirectly referred to as being part of a refugee problem that had to be solved.

Furthermore, it lacked a mechanism, based on international law, to ultimately force Israel to withdraw: all was left to the outcome of the negotiations between the parties involved. Moreover, the resolution was subject to interpretation.

The wording in the resolution with respect to Israel’s obligation to withdraw from all territory occupied in 1967(‘the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war’ as stated in the preamble) turned out to be a source of controversy.

The official French version stated: ‘retrait des forces armées israéliënnes des territoires occupés lors du récent conflit’, i.e. all territory, the interpretation of almost all other UN member states, which is in line with the UN Charter and ‘the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war’.

The official English version, however, spoke of ‘withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict’, i.e. not (necessarily) all territory, which was a reading in line with Israel’s interpretation.

The Allon Plan

On the basis of its own interpretation of United Nations Resolution 242, Israel started to implement the Allon Plan by building settlements in Palestine – in violation of international law (Fourth Geneva Convention).

Over the years both the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) have condemned this policy in a series of resolutions, but efforts to introduce punitive measures against Israel were repeatedly met with American vetoes in the UNSC and opposition from other Western member states.

With Resolution 242 the land-for-peace formula was introduced in future negotiations between Israel and the Arab States, as well as the implicit recognition of the State of Israel by Arab States. Israel, Egypt, and Jordan accepted ‘242’; Syria (and Lebanon) did so only years later. The PLO strongly opposed the resolution as it ignored the rights and political aspirations of the Palestinian people.

The UNSC designated a special representative, the Swedish diplomat Gunnar Jarring, to work with all the states involved on the implementation of ‘242’. However, this was to no avail. From March 1969 until August 1970, along the 1967 ceasefire line, Egypt and Israel became caught up in a war of attrition, with artillery bombardments and air attacks by their air forces.

On December 9, 1969, aware of the dangers of further escalation in this war in which the Soviet Union and the United States were heavily involved, the American Secretary of State William Rogers presented a plan (the Rogers Plan). In the short term, the aim was to bring about a de-escalation in the military confrontation between Egypt and Israel.

The plan called for demilitarised zones and free passage through the Suez Canal for all countries. In addition, the plan had all the ingredients for a bilateral peace agreement between the two states. Deserting the Arab front against Israel was, however, not an option for Egypt under Nasser. Similar efforts by Rogers involving Jordan were also to no avail.

History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our coverage of the history of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Fanack’s historical record meticulously chronicles the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in a chronological sequence, encompassing its origins, crises, wars, peace negotiations, and beyond. It is our most exhaustive historical archive.