In the Declaration of Principles of 13 September 1993 (Oslo-I), Israel and the PLO recognized 'their mutual legitimate and political rights'.

The Road to Oslo

The Palestinians

The exit of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) from Lebanese territory – its last stronghold in the Palestine rim countries – was a fundamental shift in the course of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The struggle of the PLO grew faint as the PLO – whose motto is the liberation of the land – was removed from the points of direct contact with the Israeli occupation; as it could no longer exercise its effective military operations through a geographical clash point with its historical enemy, like it did in Jordan or Lebanon. The PLO leadership sought refuge in Tunisia in August 1982.

In 1983, the Fatah Al-Intifada movement, which split from the Palestinian National Liberation Movement (Fatah), was formed with the support of Syria. It was infuriated with Yasser Arafat at that time because of the outcome of the siege of Beirut in 1982. The split was followed by armed operations in several Lebanese regions between the dissidents and elements of the original movement “Fatah,” who was loyal to the late Palestinian President Yasser Arafat.

These confrontations continued until 1988. Many other factions joined the fray in what was known as the War of the Camps.

The largest faction in the PLO, Fatah, had been weakened due to the tensions that afflicted the organization as a result of the Arab and regional polarization with the main Palestinian factions, which soon became a new influential factor in the conflict within the PLO. The internal unity of the organization, as one of the last influential tools in the course of the conflict with Israel, was at stake.

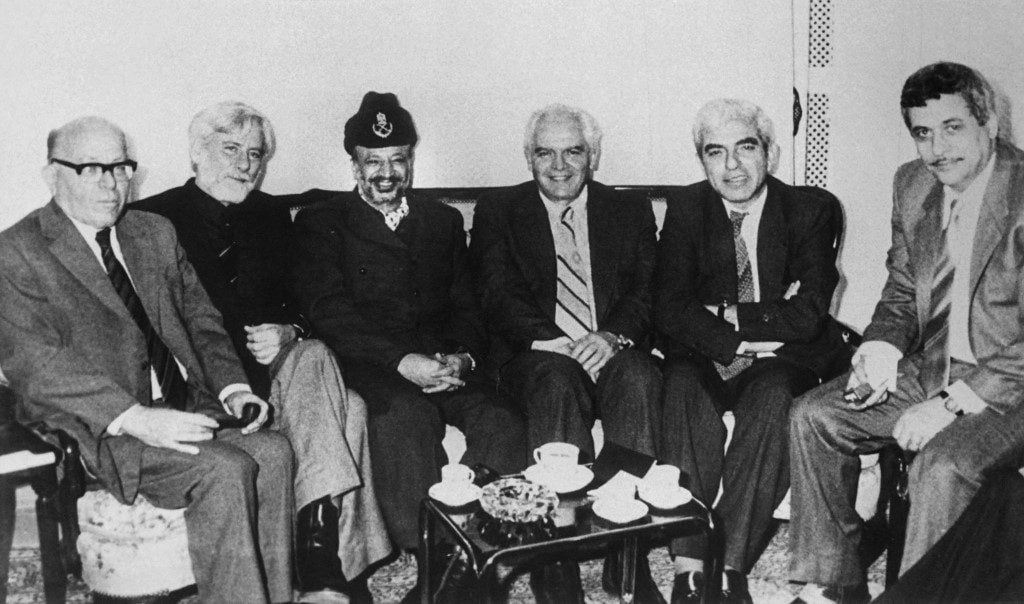

PLO leader Yasser Arafat (3rd L) meets three members of the Israeli Peace Committee, Yarcov Arnon (L), Uri Avnery, and Matti Peled (4th L) along with Issam Sartaoui (2nd R) Mahmud Abbas (aka Abou Mazen), and Imad Chakkour, Arafat’s press councilor on January 21, 1983, in a locality in Tunisia. AFP

With the eruption of the first Palestinian Intifada at the end of 1987, as one of the popularly innovative tools to keep the flame of struggle burning, the organization found – according to researchers – that accepting Security Council Resolution No. 242 as a basis for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations in 1988 would be the best way to restore its role and extricate it from its dire situation on the political landscape.

This was supported by the outcome of the 43rd session of the United Nations, in which the General Assembly recognized the declaration of the state of Palestine, issued by the Palestinian National Council on November 15, 1988. It decided that, from 15 December 1988, the name “Palestine” shall be used in the United Nations instead of “the Palestine Liberation Organization” without infringement to the observer status and functions of the PLO in the United Nations.

However, the PLO found itself in new isolation because of the consequences of the international balance of power with the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In addition, the flow of funds from donor countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Gulf states stopped, because the organization and its leader Yasser Arafat supported Saddam Hussein in the Gulf War (1991-1990) after the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait. Israel was the stronger party and the PLO was under pressure. It wanted to re-emerge on the scene and fight for the state of Palestine.

The PLO moved forward practically, to directly negotiating with Israel.

The Israelis

On the other hand, the bone-breaking policy adopted by Yitzhak Rabin’s government did not succeed in extinguishing the flame of the Palestinian Intifada, or what was called the Intifada of the Children of Stones. Israel, which was refusing to even talk with the PLO, was finally convinced that it does not make sense to have a neighbor within a stone’s throw, always consumed by feelings of resentment, so it preferred to accept – even in theory – the two-state option.

In parallel, the Madrid Conference was launched in 1991, which was sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union (at that time). The conference that was held in the Spanish capital aimed to draw inspiration from the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel in 1979, by encouraging other Arab countries to sign peace agreements with the Jewish state.

Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria were encouraged to do so, which opened a path to negotiations between the Israelis and the Palestinians for the first time under the Israeli Labor Party, whose government did not open up to peace diplomacy with the Palestinians until 1992.

Israel entered the Oslo negotiations, fully aware of Yasser Arafat and the PLO’s weakness at that time, and that Arafat was facing financial troubles due to betting on the losing horse in the Gulf War, which made him prone to more concessions, especially since he had no other options that could be considered at that time, be it international arbitration, or the option of resistance to put Israel in a disadvantageous situation if direct negotiations take place.

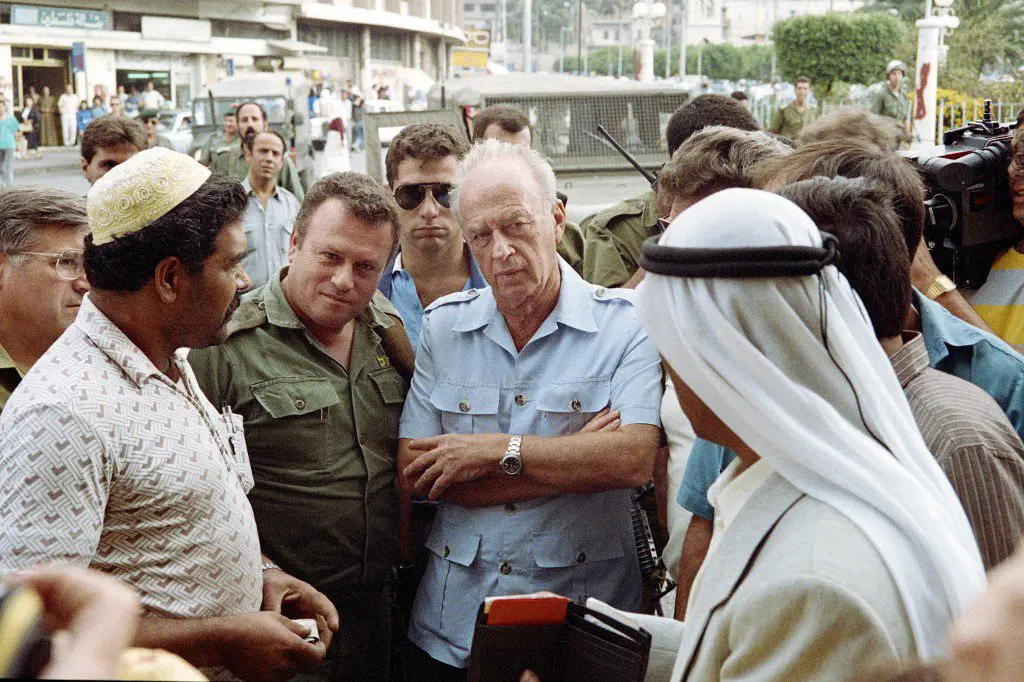

Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin (C) listens to Palestinians during a visit to Nablus on the West Bank on October 18, 1988. SVEN NACKSTRAND / AFP

After eight months and fourteen sessions of discussions, behind a thick veil of secrecy under Norwegian sponsorship, suddenly came what Jan Egeland, the then State Secretary of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, called the “first of its kind”: representatives of the Israeli and Palestinian leaders agreed to a statement containing common grounds that opened the way for the establishment of Palestinian autonomy and mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO, to be crystallized in the Oslo Accords. It called for a phased withdrawal of Israeli forces from the West Bank and Gaza and Palestinian autonomy. The PLO recognized Israel’s right to exist, and Israel recognized the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people.

Two Unequal Parties

With the pressure the PLO was facing, and the desire to re-emerge in the struggle for an independent state for the Palestinians, Israel was the stronger party in the equation and carried the biggest weight in the negotiation scale.

Circles close to the secret Oslo negotiations asserted that the room for maneuvering in the unequal relationship between the two negotiating parties was minimal because the stronger party, Israel, was the one who controlled the flow. Hilde Henriksen Waage, a historian at the University of Oslo who was assigned the task of investigating Norway’s role in the Middle East peace negotiations, says that “Norway knew this, took it for granted and knew that the negotiations had to go in Israel’s favor. Otherwise, an agreement would not be achieved.” Waage continued wondering, “But does it mean that an agreement is worse than nothing? At that moment, we always said that an incomplete peace is better than a violent war.” However, Norway was a biased mediator, according to Henriksen Waage, so the agreement reinforced this unbalanced relationship between the two negotiating parties.

Oslo I

In the Declaration of Principles of 13 September 1993 (Oslo-I), the State of Israel and the PLO recognized ‘their mutual legitimate and political rights’, promising to ‘strive to live in peaceful coexistence’, and to ‘achieve a just, lasting, and comprehensive peace settlement and historic reconciliation through the agreed political process’.

This process was made up of two phases: 1) in an interim period of five years, a Palestinian interim government would be set up in parts of Palestine; 2) after phase 1 had taken effect, negotiations would commence to find a definite answer to issues such as Jerusalem, the Palestinian refugees, the Jewish settlements, water and the borders. Unclear boundaries and the establishment of a Palestinian state were left off the agenda.

In the Madrid negotiations, the Palestinian delegation had refused to view the two issues separately, fearing that Israel only had an interest in the first phase and that the second, as a result, would not be effectuated. Both parties further agreed not to take any actions which could negatively influence or nullify the outcome of the negotiations regarding these issues.

The details about the interim administration were settled in a separate agreement on 4 May 1994, thus allowing procedures to commence, and by 4 May 1999, according to the timetable, matters should have been settled between Israel and the PLO.

Oslo II

Based on the second agreement (Oslo II) on September 28, 1995, the West Bank and Gaza Strip were divided into so-called areas A, B, and C.

Area A covered large Palestinian population areas, except for East Jerusalem and Hebron, from which Israel was to withdraw; after making some modifications, it covered about 18.2% of the total land, in which the Palestinian Authority would be responsible for civil and military administration – the Palestinians used the term “Palestinian National Authority”.

Area B, 21.8%, included the villages and their immediate surroundings, in which the civil administration was in the hands of the Palestinian National Authority, while the military administration remained under Israel’s control.

In Area C, 60%, sparsely populated areas where there were also Jewish settlements and Israeli military bases, both civil and military administration remained in the hands of the Israelis.

Outcomes

1. The Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements for Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and Jericho area was the most significant breakthrough in the century-old conflict between Palestinians and Jews in Palestine.

2. Both Oslo Accords formed a historic agreement. It endeavoured to end a long history of mutual denial and mutual rejection between the two main parties in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. While the Palestinian rejection of Israel’s legitimacy was enshrined in the Palestinian National Charter in 1968, Golda Meir, the Israeli Prime Minister between 1969 and 1974, summarized Israel’s rejection of Palestinian national rights by saying, “There is no such thing as a Palestinian people. It is not as if we came and threw them out and took their country. They didn’t exist.”

3. The two sides agreed to the principle of territorial compromise as the basis for settling their long and bitter dispute, as the basis for their peaceful coexistence. Partition was not a new idea; it was first proposed by the Peel Commission in 1937, and again by the United Nations in 1947, but was rejected on both occasions by the Palestinians.

4. Recognizing that both sides would refrain from imposing their vision on the other side. The two sides abandoned the ideological dispute over who is the rightful owner of Palestine and turned to find a practical solution to the problem of dividing the narrow stretch of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

5. The agreement ended the two-year stalemate in the Middle East peace talks under American facilitation that began at the Madrid Conference in October 1991. For Jordan, the Oslo Process had removed the last obstacle to striking a peace deal with Israel. A day after the agreement was presented to the world, in a more modest ceremony at the State Department, representatives of Jordan and Israel signed a common agenda for detailed negotiations aimed at a comprehensive peace treaty.

6. Arab reactions to the Israeli-Palestinian agreement were somewhat mixed. Arafat was given a polite but gentle reception from the nineteen foreign ministers of the Arab League who met in Cairo a week after the signing ceremony in Washington. But some member states of the League were upset, especially Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

7. Aside from internal constraints on both sides, there were inherent flaws in the Oslo Accords themselves. The agreement contains so many ambiguities and contradictions that it is open to widely differing interpretations. For the Israeli government, the agreement provides for a temporary arrangement that carries only the most general implications for the permanent transfer of territory or authority. For the PLO, the agreement is the first step toward full statehood. But the two sides could not advance together because they were intent on going in different directions.

Consequences

Both accords rested on mutually dependent agreements. The solution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was not based upon international law. In fact, the agreements made were technically illegal since according to international law territorial expansion by means of violence is prohibited. Israel should, therefore, within the framework of an agreement with the PLO, have committed to ‘total withdrawal’ from the territories occupied in 1967. However, on the basis of the Oslo Accords, the ‘degree of withdrawal’ was made subject to further negotiations. As this depended on Israel’s willingness in these matters, the end result would probably be determined by the outcome of a debate within Israel rather than by negotiations with the PLO. In addition, Arafat’s party had made concessions to Israel on many essential points for the Palestinians, and the net result was a continuation of Israeli dominance under a different guise. Nevertheless, from one day to the next, Israel’s image had been transformed from an occupying power – which had only recently suppressed the intifada with tough measures – into a negotiation partner of the PLO.

By abandoning the path of international law, the PLO committed itself to an uncertain adventure, thereby hazarding the Palestinian people’s interests. That the situation had come to this cannot be viewed separately from the organization’s now strongly weakened position: in exile in Tunis, financially destitute, and confronted with a loyal yet self-confident leadership in Palestine.

For the exact same reasons, Israel sniffed at the opportunity to come to a political arrangement on its own terms with an organization which, because of its historical role within the national movement, was still in the position to enter into agreements on behalf of the Palestinians.

To the outside world, it appeared that a historical compromise had been reached by two sworn enemies. The theatricalities strengthened this impression: historical handshakes on the lawn in front of the White House and the world’s press, Nobel prizes and so forth. Although the euphoria was initially great in Palestine, Palestinians also immediately spoke against the agreements, using powerful arguments.

History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

This article is part of our coverage of the history of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Fanack’s historical record meticulously chronicles the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in a chronological sequence, encompassing its origins, crises, wars, peace negotiations, and beyond. It is our most exhaustive historical archive.