The construction of the Wall has continued since the International Court of Justice gave its advisory opinion. The ongoing situation underscores the complex geopolitical challenges and the difficulty of translating legal opinions into tangible changes on the ground.

Introduction

In December 2003, the General Assembly of the United Nations asked the International Court of Justice in The Hague to render its advisory opinion on the question what the legal consequences were arising from the construction by Israel of the wall in Palestine.

On 9 July 2004, the Court formulated as its opinion that, first, Israel should immediately cease the construction of the wall and repeal or render ineffective all measures taken which unlawfully restrict or impede the exercise of the rights of the inhabitants of the West Bank, and secondly, Israel was found to be under an obligation to make reparation for all damage caused.

The Wall

The Government of Israel has envisaged various plans to halt infiltration from the West Bank since 1996. On 14 April 2002, it decided to erect a ‘Separation Fence’ (Decision 64/B) in the wake of the Second Intifada, when there was a sharp rise in terrorist attacks (i.e. attack on non-combatants). This decision was confirmed and specified by Cabinet Decisions of 23 June 2002 and 14 August 2002.

On 1 October 2003, the Cabinet approved a full Barrier Route in Decision 883. A draft-resolution submitted to the Security Council and condemning the construction of the barrier (hereafter the Wall) was vetoed by the United States on 15 October 2003.

On 27 October 2003, the UN General Assembly, during its Tenth Emergency Special Session, adopted Resolution ES-10/13, in which it ‘demand[ed] that Israel stop and reverse the construction of a wall in Palestine, including in and around East Jerusalem, which is in departure of the Armistice Line of 1949 and is in contradiction to relevant provisions of international law’. It also requested the Secretary-General (SG) to report on compliance with this resolution periodically.

The first report (UNdoc A/ES-10/248) of the SG was submitted on 24 November 2003. In it, the SG described the planned route and the character of what he called the ‘Barrier,’ which would consist partly of a system of fences with electronic sensors, ditches, patrol roads and coils of barbed wire, and partly of concrete walls. In particular in areas where Palestinian population centres border Israel territory, such as Qalqiliya, Tulkarm, and parts of Jerusalem.

He further noted that much of the Wall as planned or already completed deviated from the Green Line (the armistice line of 1949) and incorporated Jewish settlements and/or created Palestinian enclaves. He also described the humanitarian and socio-economic consequences for the population of Palestine.

In particular, he described the situation of Palestinians living in the enclaves as extremely ‘harsh,’ as they were often separated from their agricultural land or from their markets and services, access to which was severely hampered. In his final observations he concluded that Israel had not complied with the Assembly’s demand.

He fully acknowledged that Israel has the right and duty to protect its people against terrorist attacks, but was of the view that this duty should not be carried out in a manner that is in contradiction to international law and that could damage the longer-term prospects for peace.

Israeli and Palestinian Positions

In an annex attached to the report (UNdoc A/ES-10/248) issued by the Secretary-General (SG), the SG summarized the positions taken by the Government of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Israel justified the construction of the Wall through its right of self-defence as recognized in the UN Charter and customary international law and contended that it had contributed to a decline in the number of attacks within the country.

As for the route, it stated that neither the Green Line nor the armistice line were confirmed as international boundaries in any legal document, and that the legal status of Palestine remained disputed. It further denied that either the Fourth Geneva Convention or the Covenants on Human Rights were applicable to that territory and that, more in general, the measures taken with regard to the population of the territory were proportionate and in line with its security requirements, as required by international humanitarian law. It furthermore stressed the temporary character of the measure.

For its part, the PLO did not deny that Israel has a right to take measures to protect its legitimate security interests, but underlined that such measures should be in accordance with international human rights law and humanitarian law. The construction of the Wall, however, violated this law since it was not justified by military necessity and was not proportionate. The requirement of proportionality would more likely be met by building the Wall within Israeli territory or even on the Green Line and by evacuating the Israeli civilian nationals currently residing in the Occupied West Bank contrary to international law.

As a result of its present and planned route the Wall constituted a de facto annexation of territory and consequently an interference with the right of the Palestinians to self-determination.

Appeal to the International Court of Justice

On 8 December 2003, the General Assembly, after having taken note of the Report of the Secretary General, adopted a new resolution (ES-10/14) in which it decided to request the International Court of Justice to urgently render an advisory opinion on the following question:

‘What are the legal consequences arising from the construction of the wall being built by Israel, the occupying Power, in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including in and around East Jerusalem, as described in the report of the Secretary-General, considering the rules and principles of international law, including the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, and relevant Security Council and General Assembly Resolutions?’

The competence of the International Court of Justice (hereinafter ‘the Court’) to render such an advisory opinion is regulated in article 65, paragraph 1, of its Statute, according to which it ‘may give an advisory opinion on any legal question at the request of whatever body may be authorized by or in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations to make such a request’. Article 96, paragraph 1 authorizes the General Assembly and the Security Council to make such a request. The Court may, for various reasons to be dealt with later, refuse to comply with the request.

An advisory opinion is not binding but carries great weight as it contains an authoritative interpretation of the law as it stands by ‘the principal judicial organ of the United Nations’ (article 92 UN Charter). In case of a request for an advisory opinion the Member States of the UN and international organizations affiliated with the UN can submit written statements to the Court and, if the Court decides to hold a public sitting on the case, present oral statements.

Procedures

Within the time limit fixed by the International Court of Justice written statements were filed by 49 states and organizations. Israel submitted a comprehensive statement of more than 120 pages and 24 annexes in which it contended that the Court had no jurisdiction or at any rate should – for reasons of judicial propriety – refrain from rendering the requested advisory opinion.

A number of states – in particular the United States (which had voted against Resolution ES-10/14) and the Member States of the European Union (who had abstained) – urged the Court not to give the requested opinion since an opinion would ‘not help the efforts of the two parties to re-launch a political dialogue and is therefore inappropriate’ and might hamper progress in implementing the Roadmap process to a permanent Two-State Solution. The Member States of the European Union did not deny that the construction of the wall was not in accordance with international law (they had voted in favour of Resolution ES-10/13) but were of the view that an opinion of the Court was inappropriate for political reasons.

Hearings were held from 23 to 25 February 2004, during which representatives of fifteen States and organizations presented their arguments. Neither Israel nor the states that were against the rendering of an opinion by the Court, participated in these oral proceedings.

Court Jurisdiction

The International Court of Justice gave its opinion on 6 May 2004 (ICJ Reports 2004, p.136 ff.). It first dealt with the question whether it was competent to give the advisory opinion.

In this regard, Israel had alleged that, since the Security Council was actively engaged with the situation in the Middle East, the General Assembly had acted ultra vires when it requested the Court to give an opinion on the legal consequences of the construction of the wall.

The Court rejected this contention; the fact that article 24 of the Charter gives primary responsibility to the Security Council for the maintenance of international peace and security does not mean that it has exclusive responsibility.

The Court noted that there has been an increasing tendency for the two main organs of the UN to deal in parallel with the same matter concerning the maintenance of international peace and security, and that often the Council has tended to focus on those aspects of such matters which relate to international peace and security proper whereas the Assembly has taken a broader view, considering also the humanitarian, social and economic aspects (paragraph 27).

The Court was of the view that this practice was consistent with the provisions of the Charter and that the Court, therefore, had jurisdiction in the present case.

Political Aspects

Another argument raised against the competence of the Court was that the question addressed to it was not merely a ‘legal’ question, as required by the Charter, but that it was predominantly ‘political’ in character.

In this respect, the Court relied on its own long-standing jurisprudence, namely that ‘(w)hatever its political aspects, the Court cannot refuse to admit the legal character of a question which invites it to discharge an essentially judicial task, namely, an assessment of the legality of the possible conduct of States with regard to the obligations imposed upon them by international law. (…) (T)he political nature of the motives which may be said to have inspired the request and the political implications that the opinion given might have are of no relevance in the establishment of its jurisdiction to give such an opinion.’ (paragraph 41)

Discretionary Power

Another important question was whether the Court would act judicially wise and proper by giving an answer to the Assembly’s question. In this respect the Court recalled that under article 65 of its Statute it has a discretionary power to decline to give an advisory opinion even if the conditions of jurisdiction are met but that its answer to a request ‘represents its participation in the activities of the Organization (of the UN) and, in principle, should not be refused’. Only compelling reasons should lead the Court to decline to give an advisory opinion, which the present Court had never experienced (paragraph 43).

Nevertheless the Court deemed it useful to deal with the various arguments raised by a considerable number of States, in particular by Israel and many members of the Western group. The first such argument was that the question referred to a matter which in reality constituted a bilateral dispute between Israel and Palestine and that these had never consented to a judicial settlement of this dispute (as is required by the Statute) but had agreed that these issues should be settled by negotiation. The Court, however, was of the view that the construction of the wall must be deemed to be directly of concern to the UN since its responsibility has its origin in the Mandate and the Partition Resolution of 29 November 1947. The question is therefore located in a much broader frame of reference than that of a bilateral dispute (paragraph 50).

Another argument was that an opinion of the Court might interfere with the political process of the ‘Roadmap’. The Court, however, failed to see what influence its opinion could have on these negotiations since the participants in the proceedings have expressed different views in this respect (paragraph 53).

A third argument raised was that an opinion would lack any useful purpose since the General Assembly had already determined the legal consequences by demanding that Israel should stop and reverse its construction. Why, therefore, did the Assembly need a legal opinion on this matter? The Court, however, was of the view that it could not substitute its assessment of the usefulness of the opinion requested for that of the organ that had sought it, namely the General Assembly, and that it was for the Assembly to determine what conclusions it should draw from the Court’s opinion. Furthermore, the Court considered that the Assembly had not yet determined all the possible consequences of its own resolution (paragraph 62).

The most important argument for the Court to eventually decline to exercise its jurisdiction was that it did not have at its disposal the requisite facts and evidence to enable it to reach its conclusions. It was said, in particular by Israel, that the Court could not give an opinion on issues which raise questions of fact that cannot be elucidated without hearing all the parties to the conflict and that one of those parties (Israel) had refused to address the merits of the case.

The Court, however, was of the view that the dossier it had before it contained sufficient information and evidence to enable it to give the requested opinion. It observed, moreover, that the circumstance that others may evaluate or interpret these facts in a subjective or political manner can be no argument to abdicate its judicial task (paragraph 58).

In other words, the refusal of a state to provide the Court with the information deemed necessary by that state, can be no reason for the Court not to carry out its proper function. Nevertheless, it was the alleged lack of sufficient basic factual evidence that was used as the main argument against the advisory opinion once it was rendered.

The Court thus found not only (by a unanimous vote) that it had jurisdiction but also (by fourteen votes to one) that there were no compelling reasons for it to use its discretionary power not to give the requested opinion (paragraph 65).

Factual Analysis

The International Court of Justice addressed the substance of the question put to it by the General Assembly. It first noted that part of the wall was built or planned to be built on Israeli territory. Since the question explicitly refers to the ‘wall being built in the Occupied Palestinian Territory‘ it would not examine the legal consequences arising from the construction of those parts of the wall. The Court further remarked that, before dealing with the legal consequences of the construction of the wall in Palestine, it had to determine first whether the construction itself is in violation of international law.

The Court then gave an analysis of the legal status of that territory. It recalled the creation of the mandate for Palestine after World War I and its termination in 1948. It summarily sketched the proclamation of independence of Israel, the armed conflict between Israel and a number of Arab States and the subsequent Armistice Agreements of 1949 that, among others, established the Demarcation or Green Line. It further recalled the 1967 June War (in the West known as the Six Day War) during which Israel occupied all the territories that had constituted Palestine under the Mandate, in particular those lying east of the Green Line, nowadays known as the West Bank.

It then – again summarily – described the measures taken by Israel, in particular the Basic Law of 30 July 1980, through which Jerusalem was declared to be the ‘complete and united’ capital of Israel, the condemnation of that law by the Security Council as a violation of international law, the 1994 Peace Treaty between Israel and Jordan and the 1993 agreements between Israel and the PLO.

It observed that under customary international law a territory is considered to be occupied when during or as the result of an armed conflict ‘it is actually placed under the authority of a hostile army’ and that in 1967 Israel occupied the West Bank during an armed conflict. Israel therefore has the status of occupying Power in these territories and subsequent events have done nothing to change this situation (paragraph 78).

Legality: Rules and Principles

After a factual analysis of the route of the wall as fixed by the Israeli Government and its actual and potential impact on the inhabitants of the West Bank, the International Court of Justice identified the rules and principles that are relevant in assessing the legality of the measures taken by Israel.

The first of these is that ‘(n)o territorial acquisition resulting from the threat or use of force shall be recognized as legal’ (GA Resolution 2625(XXV) of 24 October 1970); the second is the principle of self-determination of peoples; next there are the principles and rules of international humanitarian law which are laid down in various treaties on the law of warfare and of which the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 is of particular importance since it deals with the protection of civilian persons in time of war.

Although Israel is a party to that Convention it had always denied that it was applicable to the West Bank since this had never belonged in law to Jordan, the other party to the conflict and to the Convention, which had been in actual control of the West Bank between 1948 and 1967.

From 1967 on this had been a hotly disputed issue between Israel and the United Nations and it is therefore highly important that the Court unambiguously concluded that the Fourth Convention is applicable in any occupied territory in the event of an armed conflict between two parties to the Convention, irrespective of the question whether that territory lawfully was part of the other party (Jordan) before the conflict erupted (paragraph 101).

Human Rights

The last set of rules and principles identified by the Court were those contained in the human rights conventions. Here, again, Israel had always denied their applicability to the West Bank since in its view human rights treaties are intended for the protection of citizens from their own Government and thus are only applicable within a state and not outside its territory. Moreover, in Israel’s view they are only applicable in times of peace whereas humanitarian law is applicable in times of war.

In this respect the Court repeated what it had said earlier in its advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (1996), namely, that the protection offered by human rights conventions does not cease in case of armed conflict. With regard to Israel’s contention that the human rights conventions were only applicable within its own territory, the Court found that these conventions did not intend to allow States to escape from their obligations when they exercise jurisdiction outside their national territory.

In view of the fact that Israel had exercised jurisdiction over the West Bank for more than 37 years, the human rights conventions must be considered to be applicable within Palestine (paragraph 112).

Legality: Application of the Facts

The International Court of Justice then went on to determine whether the construction of the Wall had violated the rules and principles it had found applicable. It thus applied the rules to the facts. In doing so the Court could not avoid the hot issue of the legality of the Jewish settlements. In doing so the Court touched the issue of the legality of the Jewish settlements. It noted that the sinuous route of the Wall had been traced in such a way as to include in the area between the Green Line and the Wall (the so-called Closed Area) the great majority of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem).

It then recalled that article 49, paragraph 6 of the Fourth Geneva Convention provides: ‘The occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies’. The Court thus concluded that the Jewish settlements had been established in breach of international law (paragraph 120).

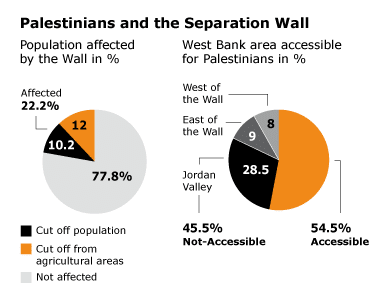

It went on to observe that the Closed Area comprises more than 16 percent of the territory of the West Bank and that after the completion of the Wall some 80 percent of the settlers, that is 320,000 individuals, would reside in that area as well as 237,000 Palestinians, whereas around 160,000 other Palestinians would reside in almost completely encircled communities. The Court therefore concluded that, in spite of the fact that Israel had assured that the Wall is of a temporary nature and that its construction thus does not amount to annexation, its construction and its associated regime create a ‘fait accompli’ on the ground that could well become permanent and thus would be tantamount to de facto annexation (paragraph 121).

Moreover, its chosen route may contribute to further alterations of the demographic situation and to the departure of Palestinians from certain areas. Thus the construction of the Wall not only gives expression in loco to the illegal measures taken by Israel with regard to Jerusalem (the annexation) and the settlements, but also severely impedes the exercise by the Palestinian people of its right to self-determination and is found to be a breach of Israel’s obligation to respect that right (paragraph 122).

International Humanitarian Law

The Court then applied a number of provisions of international humanitarian law and of human rights instruments to the facts. From the information submitted to it, it concluded, among others, that the construction of the Wall has led to the destruction or requisition of properties and to substantial restrictions of the freedom of movement of the inhabitants of Palestine in contravention of Israel’s obligations under humanitarian law.

As an example it mentioned Qalqiliya, a city of 40,000 inhabitants, which is completely surrounded by the Wall and where residents can only enter and leave through a single military checkpoint open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

As a result of the construction of the Wall, the Court also noted impediments to the exercise of the right to work, to health, to education and to an adequate standard of living as proclaimed in various human rights instruments. It observed that it is true that the applicable international humanitarian law contains provisions which enable to take account of military exigencies in certain circumstances, but considered that the measures taken were not rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.

More in general, it was not convinced that the specific course chosen for the Wall was necessary to attain Israel’s security objectives (paragraph 135).

Israel’s Right of Self-defence

The Court then dealt with the question whether the construction of the Wall may nevertheless be justified by Israel’s inherent right of self-defence (as claimed by Israel) or by a state of necessity in view of the indiscriminate terrorist attacks, originating in the West Bank, against its population.

The Court recognized Israel’s right, and indeed its duty, to respond to these acts in order to protect the life of its citizens but observed that the measures taken to that aim must remain in conformity with international law. It did not consider the right of self-defence applicable (a rather controversial finding, even within the Court itself) (paragraph 139).

Nor was it convinced that the construction of the Wall along the route chosen was the only means to safeguard the interests of Israel against the peril it had invoked as justification for that construction (paragraph 140). Its final conclusion therefore was that the construction of the Wall, and its associated regime, are contrary to international law (paragraph 142).

Court Ruling

Having reached the conclusion that the construction of the wall, and its associated regime, are contrary to international law conclusion, the International Court of Justice could finally answer the question put by the General Assembly, namely, what are the legal consequences of the violation by Israel of its legal obligations. In this respect the Court found, first, that Israel must immediately cease the construction of the wall and repeal or render ineffective all measures taken which unlawfully restrict or impede the exercise of the rights of the inhabitants of the West Bank; secondly, Israel was found to be under an obligation to make reparation for all damage caused.

Furthermore, the Court found that all other States are under an obligation not to recognize the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the wall and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction. As for the United Nations, in particular the Security Council and the General Assembly, these organs should consider which further action would be required to bring to an end the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the wall.

Finally, the Court called on both Israel and Palestine to observe scrupulously their obligations under humanitarian law, ‘one of the paramount purposes of which is to protect civilian life’, and urged the United Nations to redouble its efforts to bring the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to a speedy and negotiated solution (paragraph 163).

It is noteworthy that nearly all the Court’s findings were adopted virtuously unanimously, namely with a majority of fourteen to one. The American judge was of the view that the Court should have exercised its discretion and should have declined to give the requested advisory opinion. Consequently he also had to vote against all the Court’s findings on substance since an abstention (which in itself might have been more appropriate) is not possible under the Court’s Statute.

He, however, explicitly stated that his negative vote ‘should not be seen as reflecting his view that the construction of the wall (…) does not raise serious questions as a matter of international law’.

He felt, however, that the Court did not have before it the requisite factual bases for its ‘sweeping statements’, even if he agreed with much in the opinion. He criticized the Court, moreover (and three other judges shared this criticism) for not having examined seriously the nature of the terrorist attacks coming from Palestine and their impact on Israel and its population; he was of the view that the opinion would have had more credibility if the Court had given sufficient consideration to Israel’s legitimate concerns.

General Assembly Resolution A/ES-10/15

The International Court of Justice rendered its opinion on 6 May 2004. The General Assembly met from 16 to 20 July to consider and discuss it. At the end of its deliberations it adopted resolution A/ES-10/15 in which it ‘acknowledged’ the Court’s opinion and demanded that Israel comply with the legal obligations as identified in the advisory opinion. The resolution was adopted by a vote of 150 to 6 with 11 abstentions. Amongst those voting against were Israel and the US; the Member States of the European Union voted in favour in spite of some misgivings with regard to a number of paragraphs of the Court’s opinion, in particular on the right of self-defence.

In operative paragraph 4 of Resolution ES-10/15 the General Assembly asked the Secretary-General to establish a register of damage caused to all natural or legal persons who are entitled to compensation in accordance with the relevant paragraphs of the advisory opinion. Following a report by the Secretary-General the UN Register of Damage Caused by the Construction of the Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (UNRoD) was established by the General Assembly by Resolution ES-10/17 (adopted by 162 to 7 votes with 7 abstentions) on 15 December 2006. It has a three-member board, composed of experts appointed in their personal capacity (from Finland, Japan and the USA), and is based at the UN Headquarters in Vienna. The Board has the ultimate authority in determining the inclusion of damage claims in the Register.

Israeli Supreme Court Ruling

The advisory opinion was extensively commented upon in a judgment of the Israeli Supreme Court of 15 September 2005 in a case of complaints of a number of Palestinian petitioners against the Government of Israel. The Court rejected the International Court of Justice‘s opinion for a number of reasons, the most important of which was that the International Court of Justice based itself upon imprecise and insufficient facts and failed to take into appropriate consideration the security-military justification for the impingement of Palestinian resident’s rights.

The main difference between the position taken by the International Court of Justice and that of the Israeli Supreme Court, however, seems to be their different view on the legality of the Jewish settlements and the ensuing consequences. The Supreme Court stated that the ‘military commander is authorized to construct a separation fence in the area for the purpose of defending the lives and safety of every person present in that area’, even if that person does not fall into the category of ‘protected persons’ in the sense of the Fourth Geneva Convention but is an Jewish settler. In its view the settlers too belong to the local population whose safety has to be protected.

For this conclusion the Supreme Court does not consider it relevant to examine whether this settlement activity conforms to international law or defies it and it therefore takes no position regarding that question. But that is exactly the point on which everything hinges since in the International Court of Justice’s advisory opinion the illegality of the route of the wall, insofar as it runs east of the Green Line, is to a considerable extent conditioned on its purpose of protecting the illegal settlements within the Closed Area. The Supreme Court, however, in general takes the legality of the route for granted. It only examines, segment by segment, whether a proportional balance has been found between the security-military need and the rights of the local population since such a balance, in its view, is proscribed by the international humanitarian law on military occupation.

If it finds that that balance does not exist, the Court orders the authorities to reroute the Wall and in a number of occasions has actually done so. According to a statement by the representative of Israel in the General Assembly made in 2006, the Court has also considered 140 complaints of Palestinian petitioners and ordered close to USD 1,5 million USD to be paid in compensation.

Current State of Affairs

The construction of the wall has continued since the International Court of Justice gave its advisory opinion. According to a report of the UN Secretary-General of 6 November 2009 (UNDoc A/64/517) the wall has been extended by approximately 200 kilometres since the advisory opinion was issued, with 58 percent of the planned (709 kilometres) route at that moment constructed. According to that same report, after its finalization about 85 percent of the wall would be in the West Bank and not along the Green Line.