Introduction

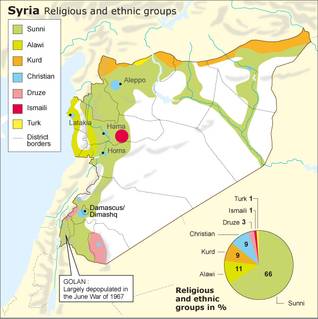

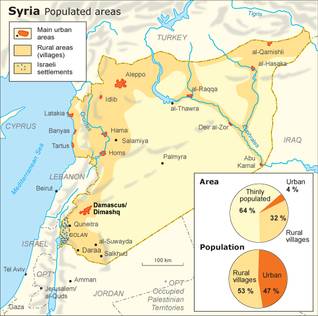

Syria’s ethnic and religious composition is fairly homogenous. The population is overwhelmingly Arab and of Sunni Muslim religious denomination. Its dominant culture is Arab Islamic. Ethnic and religious minorities have nonetheless left a significant mark on Syrian society. The population distribution is uneven, with most Syrians living in the western part of the country. An extensive desert stretches across most of Syria’s eastern territory.

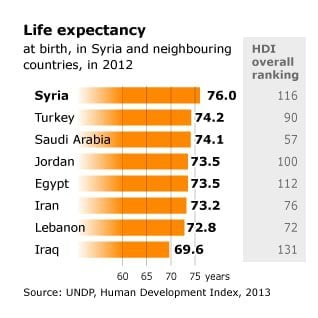

Human Development Index

In 2012, Syria’s Human Development Index (UNDP) was 0.648. Over the past thirty years, it rose by 0.77 percent annually from 0.603 in 1980. Still, Syria’s HDI is lower than might be expected from an oil-producing country, especially given Syria’s GDP. In this respect, Syria ranks 116 out of 187, below Egypt and just above Morocco, Iraq, and Yemen.

Syria scores much better where human poverty indicators are concerned (such as the Human Poverty Index, the probability of not reaching 40, or the adult illiteracy rate). Its score is significantly lower, however, on the gender-related development index (GDI). Its GDI value is 96.4 percent of its HDI value. Out of the 155 countries with both HDI and GDI values, 145 countries score better ratios than Syria (see Women).

Clans and Communities in Syria

Syria is not a tribal society, except for the semi-nomadic Bedouins, most of whom live in the Syrian deserts. Syria is – at least formally – a state in which ethnic or religious backgrounds are not supposed to play a role. It is a secular state; the President insists secularity should be maintained, even strengthened – hence the ban on wearing a veil for university students, introduced in July 2010.

Yet, there are some notable divisions, both along ethnic and religious lines. First, there is the distinction between Arabs – the vast majority – and non-Arab minorities. Syria’s official name is the Syrian Arab Republic, and its legislation stresses its adherence to the Arab culture and language. The Kurds, Armenians, and descendants of Syriacs or Arameans resent this. To say the least, their languages are neglected, and their cultures are ignored, sometimes even repressed.

There are also divisions between religious groups, particularly since the Alawites – who form only 10 percent of the population and who, in the past, belonged to the poor agricultural class – began to dominate power in the 1960s and 1970s (see Ethnic and religious composition and Relations between groups). It is not so much religion that divides the people, but rather sociological factors (power, wealth) concerning specific groups.

One of Syria’s problems is the old community system, inherited from the mandatory power. In the early years after independence, each religious or ethnic community was represented in Parliament by a certain number of seats. Each community also had its institutions and its own sets of laws concerning personal status questions (marriage, divorce, inheritance, et cetera). The military, who took power in 1949, systematically put an end to this community system – reducing at the same time the number of institutions. The Christians still have their own laws, but all Muslims, whatever their background, share the same sets of (family) laws.

Other Groups

The presidency of Bashar al-Assad, which began in 2000, saw the rise of new elites, young urban professionals from different ethnic or religious backgrounds, who share a high level of education as well as Bashar’s aspiration to modernize the country, that is, to raise the technological level and to develop the economy.

Imbalances in Syria

There are notable – regional and other – imbalances in Syria in regard to the distribution of age, work, wealth and – inversely – poverty. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, Poverty in Syria, data for 2003-2004), almost two million inhabitants (11.4 percent of the population) cannot meet their basic food and non-food needs. Using a broader definition of poverty, 30.1 percent of the population (5.3 million individuals) may be considered poor.

Poverty is generally more prevalent in rural than in urban areas (62 percent in rural areas), but the greatest differences are geographic. The north-east (Idlib, Aleppo, al-Raqqa, Deir al-Zor, and al-Hassaka), in both rural and urban regions, has the greatest incidence, depth, and severity of poverty. In contrast, the southern urban region has the least. Poverty decreased between 1996 and 2004 for Syria as a whole, but again, regional patterns varied. The incidence of poverty declined rapidly in the central and southern regions, but it actually rose in the northeast’s rural parts.

At the national level, the non-poor benefited proportionally more than the poor from economic growth. Inequality rose. In 2003-2004, the bottom 20 percent of the population consumed 7 percent of all Syria expenditure, and the top 20 percent consumed 45 percent. Again, the same regional variations were significant. However, rural-urban variations were equally noticeable: inequality in urban areas increased significantly, but it did not change in rural areas.

Most poor people in Syria live only just below the poverty line. Education is strongly correlated to poverty. More than 18 percent of the poor population is illiterate, which is most severely affected by poverty. Poverty also interacts with gender. There is a disturbingly low rate of school enrolment among poor girls. Girls in poor households in rural areas are most likely to be illiterate.

Agriculture and construction workers are overrepresented within poor groups, as are the self-employed. Moreover, the poor are more likely to work in the informal sector, which employs 48 percent of the poor. As heads of household with children, Widows are often poor and thus can be a targeted vulnerable group (Poverty in Syria, UNDP).

Crime in Syria

According to all sources, Syria’s crime rate is meager, including the (US) Overseas Security Advisory Council. However, crime rates seem to be on the rise, partly due to poverty, which has increased following the recurrent droughts (IRIN). Still, crime rates are much lower than in industrialized countries.

A car bomb killed prominent Hezbollah leader Imad Mughniyeh in Syria in 2008. Israel is suspected of being behind the attack. The high-ranking Syrian officer and Bashar al-Assad’s right hand on security, Muhammad Suleiman, was killed by a sniper in the coastal city of Tartus in August 2008.

Violent clashes between protesters and security forces have recently shaken the country.

Family Structure in Syria

Traditional Arab family values exert a strong hold on Syrian society. Even the young generations still experience close family ties. In a study among university students by the Norwegian research institute FAFO, 88 percent of the respondents said that their family was ‘essential to them; for another 11 percent, the family was ‘rather important’ (FAFO, 2008).

The man – the father – is still the head of the household in Syria. After the marriage ceremony, he receives the family book, a certificate delivered to every Syrian and Syrian-Palestinian groom, in which his wife and later his children are registered. Women are never issued with a family book, except if their husband dies, although not all widows possess this certificate. Divorced women do not possess a family book. The second or third wife of a man living in her own house does not possess a family book. The family book must obtain certain allowances (such as a heating allowance), which are accorded only to families. Single or divorced women, widows, second or third wives, and their children are not considered families.

Family laws (including inheritance laws) vary according to the religious community one belongs to (everyone has to register with a religious community, even though Syria is a secular state). In some communities, the right to divorce is denied.

Women in Syria

As in many other Arab countries, women in Syria enjoy fewer rights than men in many domains. The inheritance of Muslim women, for instance, is 50 percent of what a male receives. This hampers the small but increasing number of women heading family businesses (nine out of ten businesses are family-owned). Christian women are denied the right to divorce. In some regions, women are also prevented from inheriting as a result of local customs and traditions.

Women also tend to be poorer and less educated. Women’s participation in the labor force is 18 percent. This is the official figure, which does not consider the informal sector – in which women are predominant. In the informal sector, they have no job security or social protection. Those who do have a regular job enjoy the same rights and duties as male workers, at least in theory. Maternity leave for women who are regularly employed is 50 days, with 70 percent of their employer’s wages.

In some regions (particularly in the north and north-east), a husband may forbid his wife to see a male doctor; women in labor have been known – even in recent years – to bleed to death because the husband did not want them to go to the hospital in case a male doctor treated them. Consequently, infant mortality and maternal mortality remain higher in these regions than elsewhere, and contraception and family planning are less practiced.

Empowerment of women

However, with the help of international organizations like the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or UN Women, as well as an increasing number of NGOs, the government is trying to implement changes. Syria’s First Lady, Asma al-Assad, is very active in this field. She heads the Fund for Integrated Rural Development of Syria, which places great value on women’s empowerment.

Possibly due to Syria’s socialist orientation in past decades, the situation of women in Syria is slightly better than elsewhere in the Middle East. In 2006, Syria’s Najah al-Attar was the first woman in the Arab world to become Vice President. In 1979, the first female minister in the whole region was Syrian (today, the cabinet includes just three women out of 32 members). Since the last general elections in 2007, 31 out of 250 Members of Parliament (12.4 percent) are women. In comparison, the proportion of female parliamentary representatives in the Arab world is 8 percent, the lowest in the world, according to UNDP. In this respect, Syria comes immediately after Iraq and Tunisia.

The proportion of female members in local councils is still low, although it increased from 27 in 1975 to 189 in 1999 and 797 in 2005. In general, however, women continue to fill only a small share of leading governmental posts, accounting for 7 percent of the ministries and embassies and 20 percent in trade unions.

Girls’ enrollment and achievement are lower than that of boys in basic education (88 percent of girls reach the basic education level), but once they pass a certain threshold, girls seem to do better than boys; more than half of university graduates are females.

(Sources: Second National Report on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the Syrian Arab Republic 2005; UNDP; Poverty in Syria, UNDP; Woman Facts and Numbers, Syrian Government; Decent Work Country Programme Syria, ILO)

Youth in Syria

More than one in three Syrians is 14 years of age, or younger (36 percent in 2011). The population growth rate was 1.8 percent in 2011 (World Bank). The economy is not growing fast enough to provide jobs for the youth of Syria. Presently, the unemployment rate is estimated at 8.4 percent.

However, there are no accurate figures, and unemployment is much higher among the youth (World Bank estimate for 2010 is 19.2 percent). Syria has a population of around 20 million people, and Syrian Government figures place the population growth rate at 2.45 percent, with 75 percent under the age of 35 and more than 40 percent under the age of 15Approximately 200,000 people enter the labor market every year (IMF Country Report).

On the other hand, a significant number of the unemployed may be employed in the informal sector. A report by the Norwegian research institute FAFO made for UNICEF mentions the figure of more than 600,000 employed children aged 10-17. They were used to working long hours for little pay, and the vast majority of them were not enrolled in school(Magnitude and Characteristics of Working Children in Syria, FAFO).

Education in Syria

School education entails six years of compulsory primary education, three years of lower secondary education, and three years of upper secondary education. General secondary education offers academic courses and prepares students for university; the final two years are divided between humanities and scientific paths.

Vocational secondary training offers courses in the industry, agriculture, commerce, and primary school teacher training. This system was established in 1967 when the country signed the Arab Cultural unity Agreement with Jordan and Egypt, introducing a uniform school ladder in the three countries and determining curricula examination procedures and teacher training requirements for each level.

By the early 1980s, Syria had achieved full primary school enrolment of boys of the relevant age; the comparable figure for girls was about 85 percent. In secondary school, the enrolment dropped dramatically to 67 percent for boys, and 35 percent for girls, reflecting a high drop-out rate, which was even higher in remote rural areas.

In some Deir al-Zor governorate villages, only 8 percent of the girls attended primary school, whereas, in Damascus, about 49 percent of the girls completed the six-year primary system. In 2011, 94 percent of the boys and 93 percent of the girls were enrolled in primary education; 68 percent of boys and girls went on to secondary school in 2011, according to UNESCO figures.

The youth (15-24 years of age) literacy rate in 2010 was 96 percent for boys, 94 percent for girls (source 2008 World Development Indicators). The adult literacy rate in 2010 was 90 percent for males and 77 percent for females (total literacy rate 83 percent). (World Bank)

Child Labour

School dropout rates are relatively high, as is child labor. 0.5 percent of boys and 0.3 percent of girls in 2011 were out-of-school at the primary level. Figures for the secondary level are much higher: 9.1 percent of boys and 12.2 percent of girls dropped out from secondary school. According to the ILO report National Study on Worst Forms of Child Labour in Syria, the school drop-out rate is linked to several factors: poverty (children who instead work to support their families financially), poor quality of education, poor school accessibility, or the tendency of not sending girls to school.

The exact occurrence of child labor in Syria is difficult to define, as data from several sources contradict each other (moreover, recent data is not available). The above-mentioned 2012 ILO report cites several sources: a 2002 UNICEF report on child labor states that 12.8 percent of children between 12-14 years old and 3.1 percent of 10-11-year-olds work.

The UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) of 1999 reveals that (only) 3 percent of 10-14-year-olds work. Finally, according to UNICEF Childinfo statistics, 4 percent of Syrian children aged 5-14 are engaged in labor (based on the MICS of 2006).

Most sources agree that male child labor’s highest incidence occurs in urban areas (especially between the ages of 10-14), while female child labor mainly occurs in rural areas. Child labor increases in governorates with high population growth rates and high school drop-out rates, in addition to agricultural governorates in the north-eastern area. According to nearly all studies, most working children are either school drop-outs or have never enrolled in school.

Higher education

There are four state universities in Damascus, Aleppo, Latakia, and Homs. For a few years now, private schools and universities have been authorized, and several have been founded recently. A study among university students by the Norwegian research institute FAFO shows how fast the level of education has risen in Syria. Almost one out of five students has parents who never advanced further than primary school, while one-third stopped at the lowest secondary school level.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Syria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Protection in Syria

The structure of the Syrian labour market and the large number of jobs in the informal economy (estimated at 40 percent, see Informal sector) leaves a majority of workers without basic forms of social protection. The majority of these unprotected workers are women, who are often exposed to financial, economic, and social risks and vulnerability resulting from their need to find employment and generate income. Also, the number of migrant workers increased following the law’s adoption for the employment of migrant domestic workers in 2006, which allowed Syrians to employ foreign domestic workers. They have very little protection under Syrian law because their employment, though legal, is not regulated (Decent Work Country Programme Syria, ILO).

Civil servants, and all those employed by a state organization, benefit from a health care plan and other forms of social protection. People employed in the private sector may have some form of social protection, but it is often minimal. The ILO further writes: ‘Social protection and social safety nets to protect the vulnerable are not targeting the needed population. The existing social safety net is costly and inefficient. It cannot manage the poverty risks deriving from the country’s economic transition process. (…) The social security system, which is the oldest in the Arab region and which covers public and private sector employees for pensions and work injury, is facing severe challenges that will compromise its medium-term viability.’