Introduction

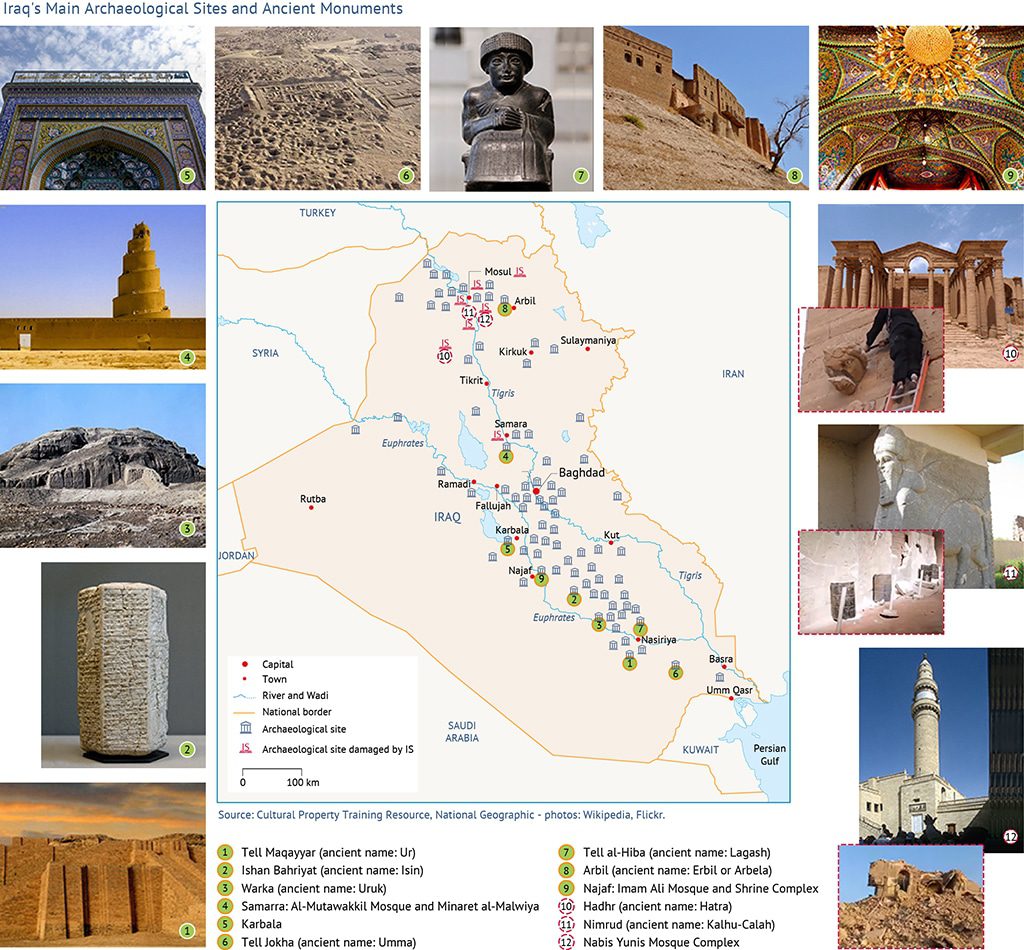

Since Islamic State (IS) captured the northern Iraqi city of Mosul in June 2014, the destruction of churches and centuries-old Islamic and non-Islamic sites, and the ransacking of museums and libraries at the hands of IS militants has captured the world’s attention.

With IS now controlling a significant part of Iraq, the country’s unique cultural heritage is more vulnerable than ever.

UNESCO, the UN organization responsible for the protection and maintenance of cultural sites, has called the attacks on Iraq’s cultural heritage a form of “cultural cleansing”. The UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on 21 May 2015 to protect Iraq’s heritage and cultural diversity.

However, this heritage – comprising remains of the Babylonian and Assyrian civilizations and other periods – was already at risk before the rise of IS.

Looting of Iraq’s treasures

The instability caused by Shiite and Kurdish insurrections against Saddam Hussein’s regime after the Gulf War (1990-1991) opened the way for the plundering of 11 of 13 regional museums in Iraq, particularly in the south and east. Thousands of artefacts and hundreds of manuscripts were stolen. Unauthorized digging at the country’s many excavation sites became commonplace. After the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, looting increased. In the first three chaotic weeks after the fall of Saddam Hussein, plunderers and art thieves – some, according to reports, working for international art gangs – rampaged through the National Museum in the capital Baghdad.

To the anger of many Iraqis and the international archaeological community, the US occupying forces did nothing to stop them. An estimated 15,000 objects were stolen; what could not be carried away was often irreparably damaged. After appeals from various quarters, including Islamic religious authorities, about two-thirds of the missing items have been returned or otherwise located. It is feared that a number of the most important pieces will never be recovered, despite the belated efforts of UNESCO, Interpol and the FBI.

Criminal gangs took advantage of the lack of security and used both old smuggling networks, established under Saddam Hussein to avoid sanctions, and newly established networks.

Archaeological sites, such as Mashkan-shapir, an ancient Babylonian city dating from 1,750 BCE and Fara, an important Early Dynastic urban settlement dating from around 2500 BCE, were increasingly attacked and artefacts removed for illegal trafficking. Aerial images published by the Global Heritage Network in 2011 showed craters and digging holes at the ancient site of Umma, evidence that massive looting had taken place there.

Threats to Iraq’s cultural heritage have also come from external elements. In April 2003, US forces built a military base, including a 150-hectare heliport, on the ruins of Babylon, bulldozing and damaging part of the site, according to the British Museum. The site had been previously damaged when new, inappropriate monuments were erected during restoration projects commissioned by Saddam Hussein.

In addition, ancient sites have been under pressure from urban development, such as residential areas on the remains of the ancient city of Nineveh.

In 2006, al-Qaeda in Iraq bombed the al-Askari Mosque in Samarra, one of the world’s most important Shia shrines built in 944. Its iconic golden dome was reduced to rubble. The attack was a catalyst for the civil war that followed. The mosque was attacked again in 2007.

Erasing remnants of ‘the other’

After capturing Mosul in June 2014, IS began to destroy Shia mosques, graves and Sufi shrines, i.e. the heritage of Muslim denominations that do not comply with IS’ strict interpretation of Islam. The Sheikh Jawad Mosque in Tel Afar, a city with a large Shia minority 56 kilometres from Mosul, was rigged with explosives and detonated. According to Human Rights Watch, IS destroyed seven Shia places of worship in Tel Afar and other places of worship in Shia villages bordering Mosul. IS militants also displaced the Shia Turkmen villagers.

IS’ campaign of destruction is not limited to Shia sites. In July 2014, the Shrine of the Prophet Yunus in Mosul, revered by Sunni Muslims, was blown up, as confirmed by both local sources and video footage released by IS. IS also razed the ancient Tomb of Jarjis, a legendary 1st-century prophet, and the associated mosque; other tombs and mausoleums were demolished in the same way. At the end of February 2015, IS destroyed the al-Khidr Mosque, built in 1133 and named after a beloved figure in Sufi Islam. The incident is part of a campaign to rid the region of all Sufi shrines.

IS has also reportedly destroyed a number of Christian sites, including the Church of the Virgin Mary north of Mosul and the 7th-century Green Church in Tikrit, one of the oldest churches in the Middle East.

In addition to capturing territory in Iraq and Syria, IS seeks to erase all remnants of other communities, religions and earlier civilizations, thereby creating the conditions for its self-declared caliphate. This includes buildings, but also other cultural artefacts such as books and antiquities. IS militants burned down the Mosul University Library in December 2014 and razed the city’s Central Public Library, reportedly leaving only the Islamic books.

In tandem with this “cultural cleansing”, IS is trying to make permanent demographic changes in north-western Iraq, according to Sajad Jiyad, an analyst at al-Bayan Centre for Planning and Studies in Baghdad. Hundreds of thousands of people from the region’s minorities (Christians, Yezidis, Shia Turkmen) have been displaced. According to Jiyad, IS militants relied on the neighbours of those it attacked to carry out the ethnic cleansing, thereby breaking up communities that had often lived side by side.

IS justifies the destruction of statues and other artefacts by condemning them as idolatrous and therefore forbidden. IS’ ideology, linked with the Wahhabi creed of Islam, rejects any form of shirk (polytheism) and idolatry.

The alleged damage to or destruction of ancient non-Islamic sites in northern Iraq made headlines in the first half of 2015. Until February, very few ancient sites had been targeted, according to Christopher Jones, a PhD student specializing in ancient near eastern history and author of the Gates of Nineveh blog. This changed after a video was released on 26 February 2015, which showed IS fighters rampaging through Mosul Museum and smashing statues with sledgehammers.

Following the video, officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Tourism reported that IS had bulldozed ruins in the Assyrian city of Nimrud and a Kurdish official reported that IS had attacked Khorsabad, a city dating back to 700 BC. However, there were no videos from IS showing the destruction of the sites; the claims came solely from government sources.

In April, another video showed militants smashing ancient sculptures of heads on the walls of the temple of Great Iwans at Hatra. While Iraqi antiquities officials claimed that IS had destroyed and levelled the site, there has been no evidence to support this claim. Another IS video portrayed militants bulldozing sculptures at Nimrud and blowing up the entire Northwest Palace.

It is important to keep in mind that reports of damage to Iraq’s ancient sites cannot always be independently verified and many of the reporting parties have their own agenda. However, it is in the interest of the Iraqi government to accurately report the damage if it hopes to win international support.

An Iraqi state official claimed that IS uses the destruction of sites as a cover for looting artefacts, destroying the ones that are too big to transport while removing the ones that can be sold. IS’ record of looting in Syria supports this claim. Some of those who monitor the field argue that IS’ interest in destroying archaeological sites is not ideological but financial, citing the alleged involvement of experienced archaeologists and contractors.