Introduction

Iraq was responsible for the first Arabic-language newspaper printed in the Arab world with the Ottoman-published Journal Iraq in 1816. This was followed by other prominent publications, such as al-Zawra in 1869, which went on to publish in Arabic and Turkish until the end of Ottoman rule in 1920. During the era of the Iraqi monarchy (1920-1958), numerous newspapers emerged and enjoyed a relatively independent media environment, although the monarchy maintained overall control.

Radio broadcasts began in Iraq in 1936 and initially proved popular because of the high illiteracy rates at the time. Iraqi listeners could also pick up broadcasts from other Arab states including Egypt, and were influenced by their dominant Arab nationalist rhetoric. Iraq was also the first Arab state to introduce a television system in 1955, an entertainment broadcast consisting of mainly British and American programming.

Following the military coup of 1958 and Iraq becoming a republic, a host of newspapers emerged representing a multitude of political and ethnic factions. Television and radio broadcasting were also significantly developed post-1958, as the country’s new rulers sought to capitalize on their reach. Successive Iraqi governments imposed greater control over the press, and newspapers were closed down at a rapid rate, to the extent that by 1968, when the Baath Party assumed power, the only remaining newspaper was al-Thawra, the party’s official publication.

By the time Saddam Hussein came to power in 1979, the Iraqi media was entirely subservient to the government. In 1986, a law was passed stipulating that the death penalty could be imposed upon anyone who insulted the president or the Baath Party. Journalists were required to register and conform to the rules of the Iraqi Journalists’ Union, headed in 1991 by Uday Hussein, the president’s son, who dismissed those who failed to praise the leadership adequately. Uday also headed a number of newspapers that emerged during this era, along with a youth-orientated radio station and television channel.

While satellite technology and foreign television broadcasts were permeating other Arab states, the Iraqi government banned household satellite dishes in 1993, and strictly enforced this measure for almost a decade. Iraq began its own satellite broadcasts in 1999, the same year as the internet was introduced, albeit heavily monitored.

After the end of Saddam Hussein’s reign in 2003, and the fall of the Baath party, the Iraqi media environment was rapidly opened up under American occupation. By 2004, over 200 newspapers had begun publishing, in addition to around 80 radio stations and 20 television channels. The Iraqi public were also quick to purchase satellite dishes and receive transmissions from abroad. A revised constitution created in 2005 enshrined media freedom, further adding to initial optimism about a new era for the Iraqi media.

However, despite the current Iraqi media being far more diverse than at any point in its history, repressive government measures, exacerbated by sectarian tensions, violence and the seizure of territory by Islamic State (ISIS), have made the country one of the most hostile environments for journalists to operate in.

Freedom of Expression

The Iraqi media environment is dangerous and repressive, ranking 158th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2016 World Press Freedom Index. Furthermore, for a fourth year in a row, Iraq was placed in the Committee to Protect Journalists’’ top-three most deadly countries for reporters to operate in in 2016.

Although media outlets were afforded far greater independence from 2003 onwards, remnants of Baathist legislation still remain and are enforced in direct contradiction with the 2005 constitution. The 1968 Publications Law, still in effect, stipulates up to seven years’ imprisonment for those who insult the government, while the 1969 Penal Code prescribes custodial sentences for defamation. As for broadcast media, this is regulated by the Communications and Media Commission (CMC), established in 2004. In 2014, as a result of the growing influence of ISIS, the CMC issued an order stipulating that all media outlets conform to ‘patriotic sense’, and refrain from broadcasting content that is contrary to the ‘moral and patriotic order’ required for Iraq’s ‘war on terror’.

In Iraqi Kurdistan, the environment is more conducive to freedom of expression, yet some subjects remain off limits and few independent media outlets operate. The 2008 Kurdistan Press Law abolished prison sentences for defamation and allowed journalists freedom of information in cases deemed relevant to public interest. However, this regional legislation is still occasionally usurped by the penal code, rendering it less effective. In 2010, Sardasht Osman, a 23-year-old journalist, was shot dead by unidentified gunmen after writing an article in the Sweden-based Kurdistan Post accusing a prominent official of corruption. Osman had previously received telephone threats ordering him to stop writing critical stories of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

Although ISIS’ control of Iraqi territory is waning, journalists operating in these areas have suffered brutal repression, particularly in Mosul where ISIS shut down all independent media facilities and imprisoned 20 journalists in 2014 alone. In April 2015, ISIS executed Thaer al-Ali, the editor-in-chief of the Mosul newspaper Rai al-Nas, after three weeks in prison, while Jalaa al-Abadi, a cameraman for the Nineveh Reports’ Network, was executed in June 2015 for alleged espionage.

Outside of ISIS-held territory, there have also been numerous instances of violence and repression against journalists in recent years. For example, journalists covering anti-government demonstrations in Baghdad in the summer of 2015 were subject to harassment and physical attacks. Journalists covering the Iraqi government and Kurdish forces’ assault on ISIS have found themselves in the line of fire. Media technician Ali Ghani killed by mortar shelling in Anbar province in August 2016, while correspondent Ahmet Haceroğlu was killed by gunfire during fighting in Kirkuk in October 2016.

The Iraqi government has targeted foreign media outlets in an effort to counter unfavourable coverage. In April 2016, the CMC shut down al-Jazeera’s Baghdad office, violating official broadcasting rules and regulations. The CMC previously suspended al-Jazeera in 2013 for ’sectarian’ reporting, after the channel covered pro-Sunni demonstrations against the Iraqi government. In 2014, the government imposed an indefinite ban on the printing and distribution of the Saudi-owned, pan-Arab newspaper Asharq al-Awsat, claiming that its operating model contravened Iraqi law.

Content published on the internet in Iraq is relatively free from government intervention, however the state maintains the ability to close down online communications nationwide, as evidenced by its annual three-hour suspension of internet services during final school exams. After ISIS seized Mosul in 2014, the Iraqi government imposed highly aggressive, albeit temporary, measures including a total internet shutdown in five provinces.

Television

A 2014 survey by the US-based Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) concluded that television was by far the most popular source of news in Iraq, with 92 per cent of respondents stating that they watched televised news at least weekly. Viewership is strongly influenced by political affiliation and sect. The most significant domestic channels are as follows:

Al-Iraqiya – Established as an Iraqi public broadcaster after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, and operated by the Iraqi Media Network (IMN), a government holding company. The channel was initially met with scepticism from local audiences who considered it to be a US-led initiative. However, it is now the most popular domestic channel in terms of weekly reach. In 2006, the channel’s chief of programming, Amjad Hameed, was gunned down by al-Qaeda affiliates, with the terrorist group citing the channel’s ‘broadcasting lies’ as the reason behind the assassination.

Since the 2014 ISIS offensive, the channel’s programming has become significantly more patriotic and propagandist in tone.

Al-Sharqiya – Iraq’s first privately owned satellite channel was established in 2004 by Iraqi media mogul Saad al-Bazzaz, a former media chief during Saddam Hussein’s reign who subsequently became a dissident. The channel has often criticized government policies and attracted controversy. It was temporarily closed in 2007, after referring to Saddam Hussein as ‘president’, and again in 2013 by the CMC alongside other channels for allegedly fuelling sectarianism.

Baghdadia TV – Pro-Sunni private satellite channel that launched in 2005 from Cairo, Egypt.

The channel gained international notoriety in 2008, when one of its correspondents threw his shoes at former American President George W. Bush. In March 2016, the CMC revoked the channel’s license and its Iraq-based offices were closed down. Staff claimed the move was in response to the channel’s ‘9 o’clock’ programme, which focused on government corruption. The CMC had previously revoked Baghdadia TV’s license in 2014, although its satellite broadcasts from Cairo continued.

Al-Sumeria – Private satellite channel that was founded in 2004. The channel airs a significant amount of entertainment content but also features several weekly talk shows covering politics and social issues.

Kurdish channels – Established in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1999, Kurdistan TV was the region’s first Kurdish-language satellite channel. It is owned by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and therefore airs pro-KDP news and informational content. Subsequently, in 2000, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) established Kurdsat as the region’s second Kurdish-language station.

Radio

According to the BBG 2014 survey, 19.7 per cent of Iraqis listen to the radio each week for news. Republic of Iraq Radio is a state-owned national service operated by IMN that provides news and current affairs content. IMN also runs Holy Quran Radio, a station dedicated to religious broadcasts.

Voice of Iraq was established in 2003 as a private station in Baghdad. It has a pro-Shiite stance and broadcasts news content in Arabic, English and Turkmen. Radio Dijla, established in 2004, is another private station with a diverse range of Baghdad-based discussion topics and audience phone-ins. Sumer FM is the sister station of al-Sumeria TV, with a similar focus on entertainment. Finally, al-Mirbad was established in 2005, in conjunction with BBC Media Action, as a news radio station for southern Iraq. It is believed that over 1.5 million people listen to the station at least once per week, although its reputation has come under scrutiny locally in light of its British and American funding.

Following its seizure of Mosul in 2014, ISIS established al-Bayan radio station and broadcast its propaganda from the city. The al-Bayan offices were destroyed in 2017.

Press

Print media consumption in Iraq is similar to that of radio consumption, according to the BBG 2014 survey, with about one fifth of Iraqis reading a newspaper at least once per week. Almost all Iraqi newspapers are funded by a political or religious party, leading to a partisan environment where credibility is often in doubt. Reliable circulation figures are also extremely difficult to obtain, but several of the most prominent daily publications are as follows:

Al-Zaman – Established in 1997 by Saad al-Bazzaz, al-Zaman began publishing from London where al-Bazzaz was living in exile.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, the newspaper opened offices in Iraq and published a dedicated Iraqi edition. In 2005, it was revealed that the publication received substantial funding from Saudi sources.

Al-Sabah – Founded in 2003 and sponsored by the state-owned IMN. As such, the newspaper enjoys privileged access to government and military sources. In 2004, the former editor-in-chief, Ismael Zayer, resigned after accusing the US coalition of editorial interference. He went on to establish al-Sabah al-Jadid in the same year.

Al-Mada – Established in 2003 by Fakhri Karim, a former Iraqi communist, al-Mada has garnered a reputation for airing relatively leftist views in comparison with other publications, albeit with a primary focus on society and culture.

Al-Adalah – Pro-Shiite newspaper owned by the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq.

Al-Bayan – Established in 2003 by the Shiite Dawa Party, the newspaper often serves as the mouthpiece of the Iraqi prime minister.

In Iraqi Kurdistan, newspaper publication is dominated by the PUK and KDP. The PUK publish the dailies Rozhnama and Kurdistani Nuwe, while the KDP publish Khabat. Independent publications such as Hawlati and Awene are also popular among Kurdish audiences, although for funding and logistical reasons they print weekly or biweekly.

Online Publications

Iraqi news websites benefit from little government intervention but also suffer from the country’s limited internet access. Some websites such as Iraqi News and Shafaq News have proven popular among domestic and international audiences because they provide news from Iraq in English and Kurdish respectively.

Other websites serve to provide specific content for certain political trends or religious figures in the country. For example, Shiite leader Muqtada al-Sadr established the popular al-Sadr Online in 2008, to provide news and information pertaining to the Sadrist Movement, while the pro-Sunni website Quds Press is popular among the country’s remaining Baathist supporters.

In 2005, the Berlin-based NGO Media in Cooperation and Transition established Niqash.org, a news website publishing in Arabic, English and Kurdish, with correspondents based in Iraq and editors working from Berlin. The website aims to provide impartial news and socio-cultural information about Iraq.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Iraq’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media

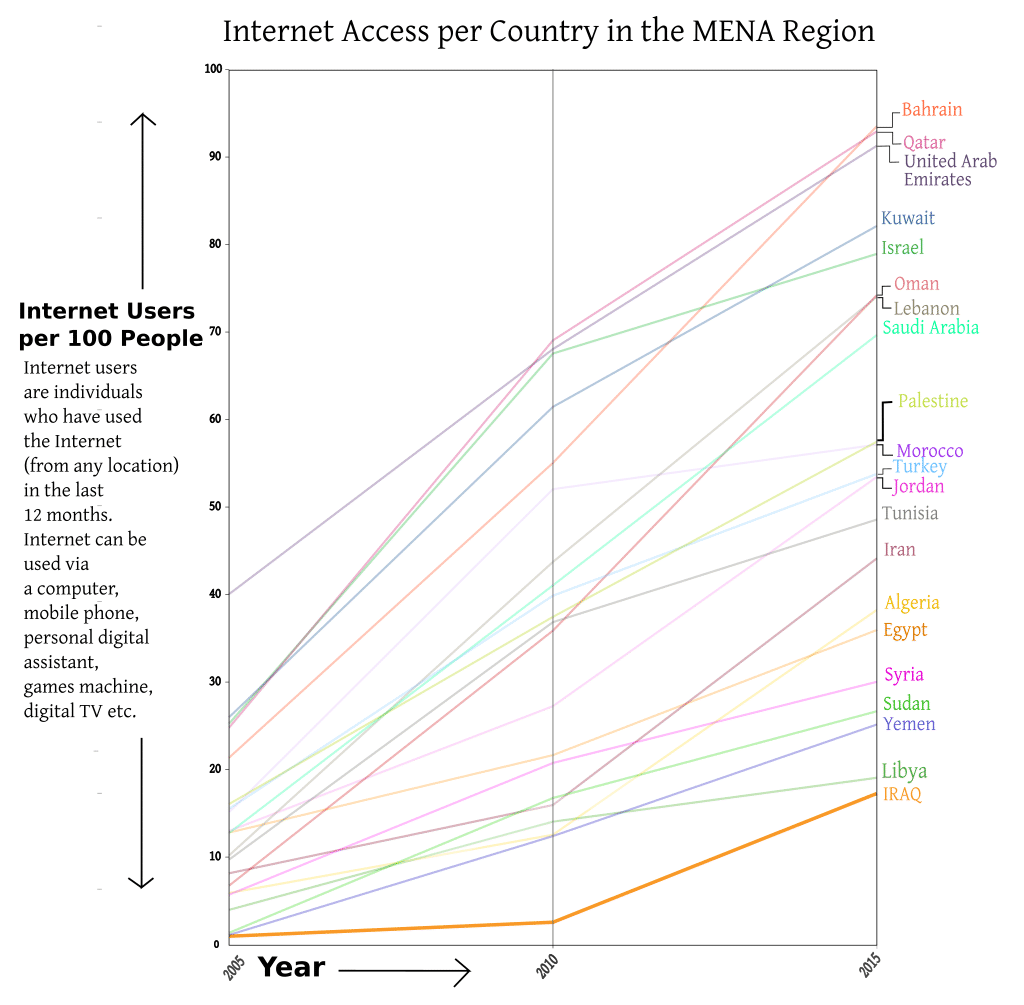

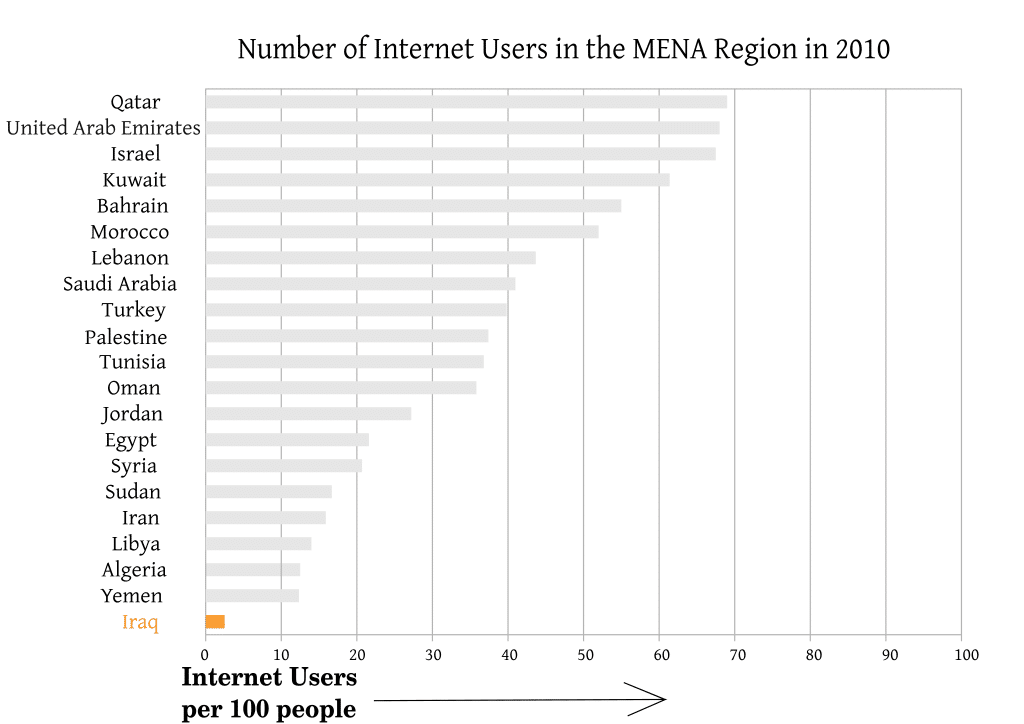

Iraq has the lowest internet penetration in the Middle East, standing at 17.2 per cent in 2015. Nevertheless, social media is popular, with approximately 30 per cent of BBG survey respondents claiming to use a social media platform at least once per week. Among respondents, Facebook was by far the most popular platform, with 94.3 per cent of social media users accessing it, followed by Google+ (41.8 per cent) and Twitter (25.8 per cent).

The rise of ISIS has led to an increased use of social media in the country, both by proponents of the terrorist organization and citizen journalists documenting efforts to combat it. Iraqi journalist Ali Wajih has amassed over 80,000 Facebook followers for his page dedicated to sourcing information about counter-ISIS battles. He has received praise for his non-biased reporting, which is seen as more credible than official government accounts. Citizens have also used social media to pressure the Iraqi authorities into taking more action against ISIS, with an April 2015 Facebook campaign criticizing the government’s failure to rescue besieged soldiers at the Nazim al-Tharthar dam and calling for protests.

The Iraqi government is well aware of the potential of social media for both ISIS supporters and ordinary citizens. In 2014, it imposed a nationwide shutdown of all social media and instant messaging services as it sought to restore order amid the ISIS territorial advance. However, many citizens were able to circumvent the ban by using proxy software.