In the Spring of 2008, the al-Maliki government decided to curb the activities of the Mahdi Army (Jaysh al-Mahdi), the militia of the Shiite Islamist leader Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr. In two major offensives (in March-April and in September) in Basra and Baghdad, the Iraqi army, backed by US and British airpower, made the Sadrist forces lay down their arms (after Iranian mediation). And so, from the latter part of 2008, the situation in the Arab part of Iraq began gradually to calm down, thanks to the co-optation of former Sunni Arab fighters, the weakening of the Salafist jihadis, the curbing of the Mahdi Army, and the effects of the sectarian and ethnic cleansing of mixed areas.

In the Spring of 2008, the al-Maliki government decided to curb the activities of the Mahdi Army (Jaysh al-Mahdi), the militia of the Shiite Islamist leader Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr. In two major offensives (in March-April and in September) in Basra and Baghdad, the Iraqi army, backed by US and British airpower, made the Sadrist forces lay down their arms (after Iranian mediation). And so, from the latter part of 2008, the situation in the Arab part of Iraq began gradually to calm down, thanks to the co-optation of former Sunni Arab fighters, the weakening of the Salafist jihadis, the curbing of the Mahdi Army, and the effects of the sectarian and ethnic cleansing of mixed areas.

Prime Minister al-Maliki personally tried to claim credit for this state of affairs, having targeted Sunni Arab fighters, a Shiite militia, and Kurdish peshmergas. His nickname became ‘Mr. Security’. His standing among Iraqis further improved because of the outcome of the negotiations he and his government held with the United States concerning an end to the occupation of Iraq. In the beginning, Washington aimed to keep a military presence in Iraq for an indefinite period (based on the ‘Korean model’). To all Iraqis – except the Kurds, who need US support against old and new enemies – this was an unacceptable proposition.

Agreement on withdrawal US Forces

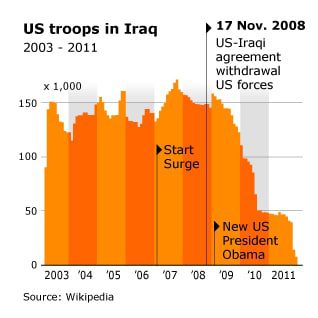

After several months of tough negotiations Washington conceded, and on 17 November 2008, in the final days of the Bush administration, a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) was reached between Baghdad and Washington (later approved by Parliament and the Presidency Council).

Under this agreement: 1) US combat troops would first withdraw from urban areas by 30 June 2009; 2) the number of American combat forces would be reduced from about 125,000 to 50,000 by 31 August 2010; the remaining American forces would be involved in training and assisting the armed forces of Iraq, and 3) all American forces would leave Iraq by 31 December 2011. It would thereafter be up to the government of Iraq to make security arrangements with the United States. At the request of several Iraqi parties, the agreement would require the approval of the people of Iraq by a referendum planned for July 2009, but which did not take place, then or later.

In addition to these successes, Prime Minister al-Maliki tried to establish himself as a kind of a new ‘strong man’, attempting to run a divided society. His first test came with the provincial elections of 31 January 2009 (because of political disagreements between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Baghdad, these elections were postponed in Kirkuk).

For al-Maliki and his State of Law Coalition, these elections paid off well, at least among Shiite Arab voters. Important players, such as the Shiite Islamist Supreme Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI; renamed from SCIRI in May 2007) and the list of Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr, lost a lot of ground to al-Maliki, in Baghdad, Basra, and elsewhere. On the other hand, because al-Maliki got almost no votes from Sunni Arabs (or Kurds), his ambition to become a ‘national leader’ was seriously dented.