Introduction

As in other developing countries, there is a huge gap between the city and the countryside in Iraq. City-dwellers and villagers live, literally and figuratively, in different worlds. For example, in the cities, Islamic law and practice to a certain extent shape the facets of daily life, while in the countryside life is ordered primarily by traditional loyalties based on blood relations.

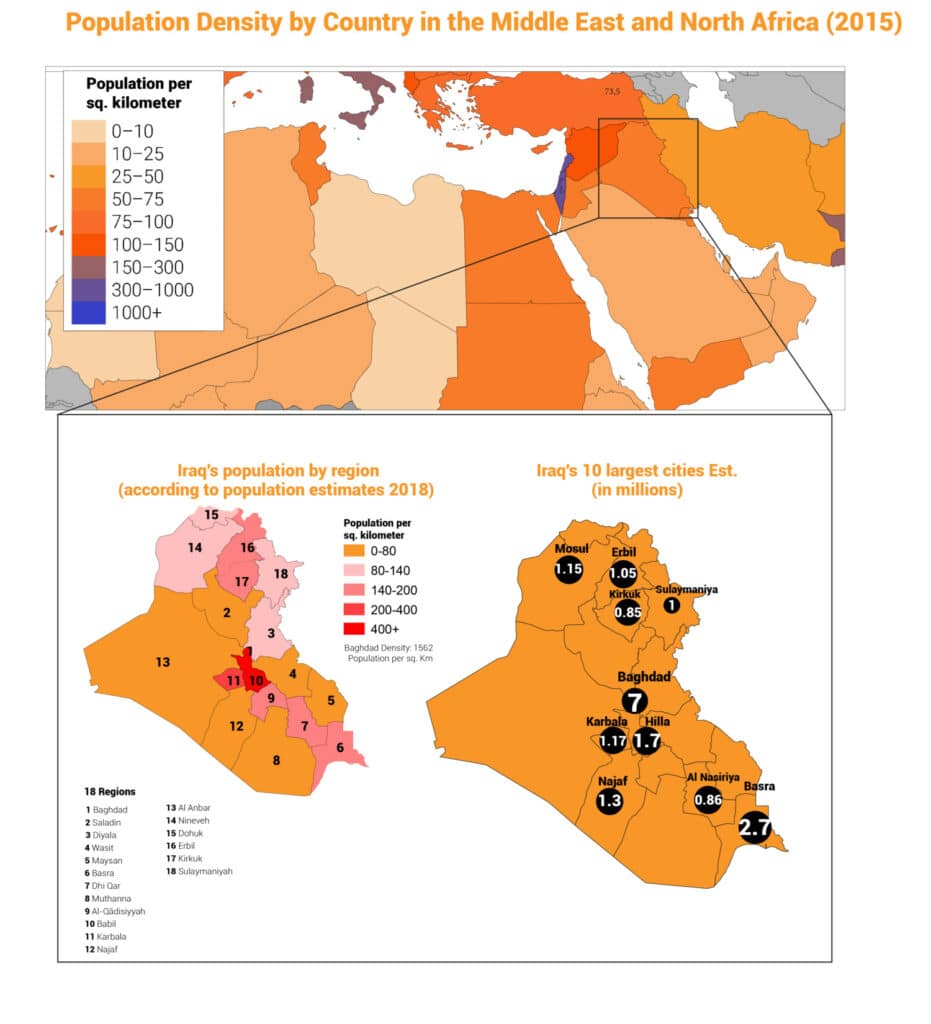

The dichotomy between city and countryside is not, however, absolute. From the early 1940s a massive movement from the countryside to the city began. In 1930 one quarter of Iraq’s population lived in cities; in 1960 that had risen to half, and that figure presently stands at 67 percent. In two generations, the demographic balance between city and countryside had tilted entirely from one side to the other.

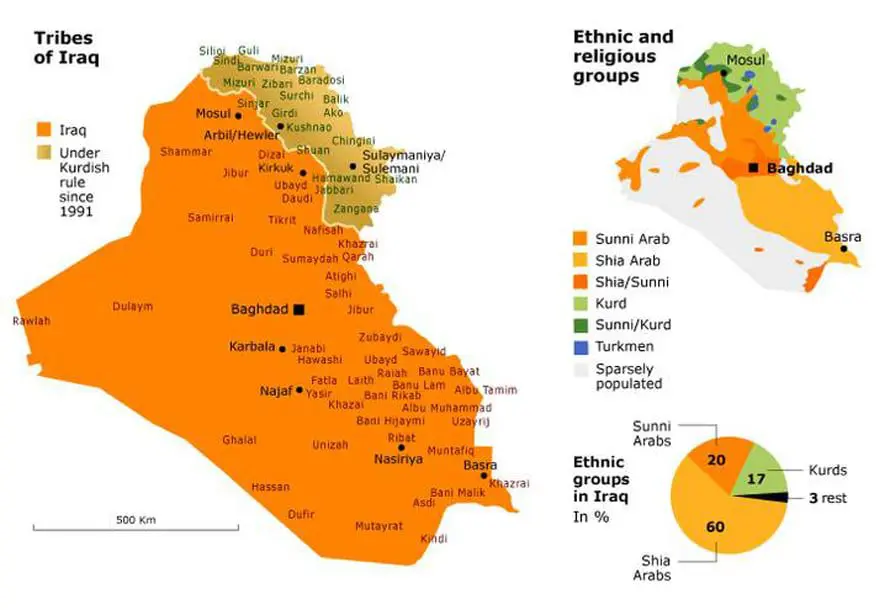

For city-dwellers, their own background continues largely to determine their behaviour. Their houses, often made of reeds and mud, look like the houses in the region from which they came. Migrants to the city generally settle in neighbourhoods where others from the same tribe or area – and thus of the same religious persuasion – have settled. These neighbourhoods are thus ethnically, religiously, and tribally homogenous. Just as in tribal or village society, people there can fall back on others with a common background for protection and support.

The strong concentration of various population groups in certain parts of the country and the separate housing patterns in the cities inhibit intensive contacts between groups, and ethnic, religious, and tribal divisions are sometimes reinforced by economic inequality. Thus, before the 1958 revolution in Iraq, much of the land in the south of Iraq was in the hands of Sunni Arab landowners, while it was worked by Shiite Arab tenant farmers. Around Mosul Arab farmers worked the land of Turkmen landowners.

Satisfying Honour and Blood Retaliation

Satisfying honour and blood retaliation are social mechanisms of pre-Islamic origin (although they are largely sanctioned by the Sharia, or Islamic law). Similar mechanisms are to be found also in non-Islamic societies, as in Christian southern Europe.

People resort to satisfying honour when their family’s reputation is damaged. In many cases, these situations arise from illicit contacts between men and women. Traditional societies do not permit unsupervised contact between males and females who are not married to one another and who could have sexual relations with one another. For minor violations the punishment is a beating or confinement at home for the woman.

The consequences are more serious when illicit sexual contact has taken place. In these cases the woman involved may be killed by her father or brothers, in order to cleanse the family’s honour (when a family becomes known as ‘bad’, all its members are involved). Even when the transgression involves a married woman, male members of her family take action, and the deceived husband stays out of the picture.

In the case of illicit sexual contact, violence can also be used against the male partner, but only in cases in which the woman’s family, in light of their power and influence, do not fear repercussions from the man’s family. Affairs of honour cannot be satisfied by monetary payments.

The basic principle behind blood retaliation is, that where blood has been shed, it must be paid for in the same way – the Biblical eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. When someone is killed by an act of violence, there are three options for the families of the perpetrator and the victim: 1) the victim’s family can demand that the perpetrator’s family deliver the perpetrator to them, or kill him themselves; 2) the victim’s family agrees to accept blood money, the amount of which is established in negotiations; 3) the victim’s family agrees that an unmarried woman from the perpetrator’s family be forced to marry a member of the victim’s family, so that the families are reconciled with one another through marriage.

These three options are mutually exclusive; only one will apply in any given case. The blood-money option is generally chosen, except in the case of a particularly gruesome or premeditated murder, when blood money is rarely accepted.

If, in the absence of a settlement, the victim’s family commits violence against a random member of the perpetrator’s family, they violate the Sharia. The Sharia, like Western law, respects the principle that the perpetrator, and only the perpetrator, is responsible for his act.

It is not only members of traditional communities, especially in rural areas, who think and act in this way: affairs of honour and blood retaliation are also found in cities and diaspora communities.

Urbanization

Two factors have dramatically accelerated migration to the city. The initial flood of migrants to the city was an unforeseen consequence of the privatization in the 1930s of land that had previously been administered collectively by tribal units. Unfavourable land-tenure conditions caused the impoverishment of a large part of the rural population, and growing numbers of them sought a better future in the cities.

The process of urbanization was also hastened by the growing commercial activity in the cities, which resulted from the rise of the oil industry. During the economic boom of the 1970s wages in the city were double those in rural areas. In order to prevent the countryside from being depopulated, oil revenues were, in the 1970s, invested heavily in rural infrastructure (education, health care, electrical power, roads, etc.).

Migration to the cities had far-reaching consequences for the labour force. In 1920 three-quarters of the labour force worked in agriculture. In the mid-1950s this percentage had fallen to half and, by the beginning of the 1990s, to one-third. About half were now employed in industry, construction, and mining, and about 40 percent in the fast-growing service sector. Participation by women in education and labour also grew during the years of strong economic growth.

By 1985 women made up 19 percent of the working population, an extremely high percentage in the Islamic/Arab world. This figure does not include women in rural areas, who traditionally play an important part in agriculture. Because of the dramatic economic consequences of the wars with Iran and in Kuwait, economic and social development largely came to a halt.

Family, Clan, Tribe

Iraqi society is organized differently from Western, post-industrial society. There is a strong orientation to the family and the clan (which consists of several families). About 40 percent of the population are also loyal to their own tribe (which consists of several clans). There are about a hundred large tribes and twenty-five tribal confederations.

The existence of the tribes dates from far before the rise of Islam. In the Ottoman Empire, efforts were already being made to restrict the power of the tribes and to bind nomadic tribes to one location. With the introduction of the Land Registration Act in 1932, most of the tribal leaders became large landowners and were integrated into national governance in some way. Land reforms after the 1958 revolution and the massive movement to the cities undermined the tribes’ economic and social position, to the benefit of the central state.

After the coup d’état in 1968, the scales again tipped in the other direction. In an attempt to secure the centre of power, President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and his cousin Saddam Hussein placed power in the hands of the members of their own Sunni Arab clan and the Sunni Arab tribes connected with it. Traditional loyalties thus came to be critically important at the highest political and military levels.

On the other hand, a growing number of Iraqis fell back on family, clan, and tribe, to protect themselves against the encroachment of the police state and later also for economic survival in a country ravaged by war and economic sanctions. The regime also mobilized the tribes to maintain peace and order in the countryside after the outbreak of the war with Iran in 1980. Over the past two decades, new life has thus been breathed into traditional structures in Iraqi society, from the top down and from the bottom up.

There is a rigid hierarchy in the traditional extended family, in which several generations (parents and their children, grandparents, brothers with their families) live under the same roof. Authority lies formally in the hands of males, who are ranked according to age and social position. Among women, authority increases with age and number of children. An Arab father takes the name of his firstborn son or daughter, preceded by Abu (father of…), and a mother takes the name of her firstborn, preceded by Umm (mother of…).

Nuclear families, composed of parents and children, predominate in today’s cities. To this unit are sometimes added the husband’s grandparents or his unwed sister (who, even if she is an adult, is deemed incapable of living alone; this is not true of a widow).

Arab and Kurdish societies are patrilineal. Upon marriage, a woman leaves her family and enters the family of her husband. In addition to being a union between two people, a marriage is seen as an alliance between two families. Children from the marriage are counted as members of the husband’s family. In the case of divorce, the woman loses her children and returns to her parents or brothers.

These traditional social relationships impose immense social pressure and control. Individual conduct is tightly regulated, and violations of unwritten laws are punished. Family honour is regarded as the highest good and defines a family’s prestige in relation to other families. Violations of traditional rules and customs, such as improper contacts between men and women, are regarded as a blot on the family honour and punished with physical violence, in order to redress the harm done to the family.

Violence can be used in response to violence. According to Islamic law, questions of honour and acts of violence should be laid before an Islamic court for judgement and punishment, but this generally does not happen, particularly in rural areas: people take the law into their own hands, sometimes acting in complete disregard of Islamic law.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Egypt’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: