In the early morning of 22 February 2006, a large bomb explosion almost completely destroyed one of the most important Shiite shrines, the al-Askariya Mosque in Samarra (80 miles north-west of Baghdad), the burial place of two Imams, Ali al-Hadi and Hasan al-Askari, and the place where the twelfth or ‘hidden’ Imam, Mohammad al-Mahdi, vanished in 873 CE. No one was killed, but the impact on the Shiite community was huge.

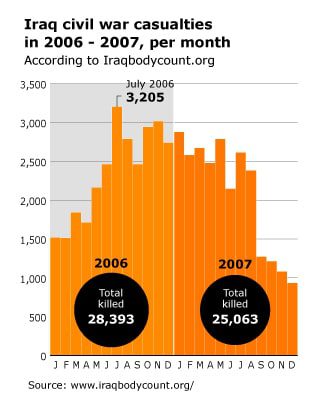

Shiite fighters took revenge on a large scale by attacking Sunni mosques. Random killings in mixed neighbourhoods of such big cities as Baghdad began to take place, with the objective of ‘cleansing’ these places of Sunni Arabs, bringing, in turn, revenge attacks on Shiite Arab civilian targets. In those days, being in the wrong place at the wrong time could mean losing one’s life. Armed Sunni and Shiite groups (some with links to the state apparatus) were mainly responsible for the atrocities. The number of casualties quickly rose to unprecedented levels. Rapidly increasing numbers of Iraqis living in mixed areas were forced to flee their homes. They were either internally displaced or became refugees in neighbouring countries. In 2006 and 2007, their number would reach millions (the often mentioned figure of 4 million seems, however, unfounded). Half of them, predominantly Sunni Arabs, ended up in Syria and Jordan. Shiite Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, and others sought refuge in the relatively quiet Shiite Arab (southern) and Kurdish (northern) parts of the country. The material and economic damage also were extensive. The threat of outside interference in the form of support to clients increased (Saudi Arabia and Syria to the Sunni Arabs, Iran to the Shiite Arabs).

US-British occupying forces – responsible under international law for maintaining law and order – lost whatever control they had over the developments on the ground, and they watched central Iraq slide into civil war. This, as well as rising military losses, the financial burden, and growing criticism of the occupation (and the war itself) in the United States and elsewhere, led in 2006 to a fundamental military and political reorientation of Washington’s Iraq policy. The process was hastened by the dramatic defeat of President George W. Bush’s Republican Party in the mid-term elections on 7 November 2006. At about that time a bipartisan commission in Congress, the Iraq Study Group, offered the government ideas for a new approach (i.e., an exit strategy).

This reorientation led, in the spring of 2007, to a temporary increase in the number of American soldiers, combined with the introduction of new counter-insurgency tactics, a policy called the Surge. Of more effect, however, were the efforts made to try to co-opt Sunni Arab armed fighters and get them involved in a policy aimed at neutralizing the Salafist jihadis, especially those of al-Qaeda in Iraq. After having lost the bloody confrontation with the Shiite Arabs, leaders of Sunni Arab armed groups, many of them tribal chiefs, needed support and were willing to change sides. It led to the formation of a large US-financed Sunni Arab militia, the so-called Awakening (Sahwa) Councils, also known as the Sons of Iraq. Their efforts soon led to a dramatic decrease in the highly polarizing violent activities of the Salafist jihadis.

This alliance of convenience translated itself into more US support for the political demands of the Sunni Arabs. This was an alarming development, especially for the Kurds, because several important articles of the Constitution, which had been agreed upon with their Shiite Islamist SCIRI partners, had not yet been implemented: the division of power between the central government and those in the separate regions; control over, and division of, oil revenues; and the future status of the province of Kirkuk and other disputed territories.