In August 1990 Iraqi tanks breached the Kuwaiti border and helicopter borne troops landed in Kuwait City, in a culmination of rapidly deteriorating relations between the two countries. In the weeks before the invasion the Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had accused the Gulf state of tapping oil out of fields that straddled the border of the two countries. The US ambassador in Baghdad, April Glaspie, had told the Iraqi leadership that the United States would not interfere in inter-Arab affairs, an opinion that Saddam Hussein interpreted as a green light to seize Kuwait, a country many Iraqis considered to be a province of Iraq proper.

Operation Desert Shield

The small Kuwaiti Armed Forces were no match for the Iraqis, who allegedly numbered more than 100,000. Many Kuwaiti army units, aircraft and navy vessels fled to Saudi Arabia, waiting for the tables to turn. They did not have to wait for long. Fearing the Iraqi forces would continue their advance into eastern Saudi Arabia – where the world’s largest oil reserves are situated – the surprised United States sent thousands of airborne troops to Saudi Arabia within days, to form a trip-wire on the northern border (Operation Desert Shield). Soon, this lightly armed ‘speed-bump’ was reinforced by tens of thousands of troops with their equipment. Some were from the United States, others from Germany, where American soldiers at that time were being reduced due to the easing of tensions between East and West. The American naval presence also increased dramatically with the arrival of several aircraft carriers. Reinforcements were also brought in on the diplomatic front. More than thirty countries promised to send troops, France, Great Britain and a coalition of Arab countries sending sizeable forces. In the meantime Iraqi forces dug in, in Kuwait and in the southern provinces of Iraq itself. Iraq also paraded hostages whom it had seized aboard a British Airways plane that got stranded in Kuwait.

Operation Desert Storm

At the beginning of the winter hundreds of thousands of Coalition troops had arrived in the ‘Theatre of Operations’. It became all too clear that their presence was not just intended to check an Iraqi invasion of Saudi Arabia, but to evict the Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Then, in January 1991, Operation Desert Shield turned into Operation Desert Storm with an aerial campaign that was to last about six weeks. In a move that is still considered mysterious, dozens of Iraqi fighters of modern build fled to the former arch-enemy Iran. To this day, most of these aircraft are in service with the Iranian Air Force.

Most of the Iraqi forces had dispersed and dug in under metres of sand and behind sand works. However, this did not provide an answer to the Coalition’s air supremacy over the Kuwaiti battle front. The Iraqi forces came out of the aerial bombardment relatively unscathed. There were just too many targets and precision bombing with guided munitions was relatively infrequent. But the air assault had a devastating effect on the moral of the Iraqi rank and file, who were like sitting ducks with little certainty about the vicissitudes of the war. Especially the American use of very heavy bombs that produced mushroom clouds, was a powerful psychological weapon.

After two weeks of bombardments, the Iraqi army decided to counter-attack with several armoured divisions. Their objective: the border-town of Khafji. As soon as the dispersed Iraqi tanks and other armoured vehicles formed columns and moved south, they were detected and followed by radar planes, which subsequently directed attack aircraft to these targets in the desert. Most of the Iraqi formations did not reach Khafji as a result of the aerial attacks, with the exception of some troops that were fought off on the outskirts of Khafji. It was the only Iraqi counter-attack of the war.

Armistice

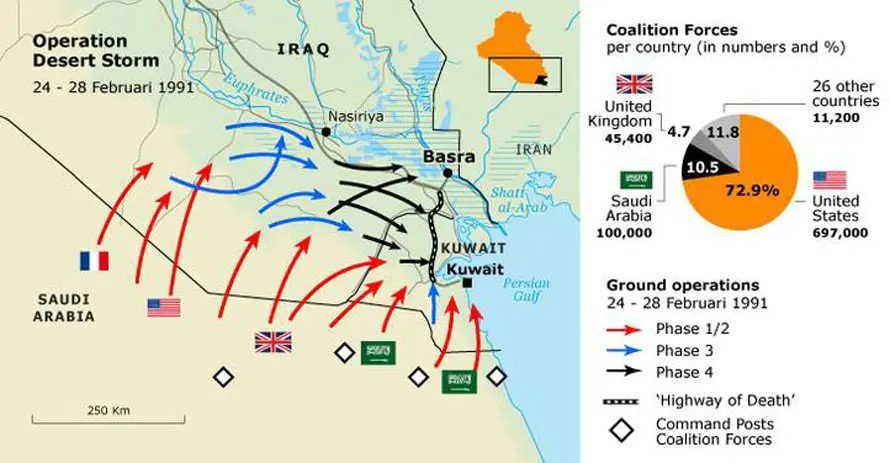

Cut off, the Iraqi military headquarters in Baghdad had huge problems obtaining the required situational awareness. Wireless communications were jammed continuously, and the few ground cables that ran all the way to the south, were severed. The Iraqi generals based their intelligence more and more on public cable television and radio. When Western media extensively reported on large-scale exercises by American and British amphibious forces and rehearsal of urban warfare, the Iraqi generals concluded that the main Allied thrust would be in the direction of Kuwait City, with supporting amphibious landings from the Gulf waters. Instead, the main attack of Coalition formations was directed around Kuwait at the rear of the Iraqi occupation forces. No landings took place.

The diversionary attack on the main Iraqi defensive line in Kuwait proceeded more quickly than expected. When it became clear that the Iraqi occupation forces in Kuwait were threatened with encirclement, they tried to withdraw to Basra. En route they were attacked by American naval planes. Shortly afterwards the armistice was signed. This did not signal the end of the hostilities, however. Indeed the largest tank battle took place when Iraqi armoured formations tried, in violation of the cease-fire agreements, to flee from the south of Iraq to safer areas, away from nearby American troops. The battle for Easting 73, as it became known, is still being fought, virtually, at American military academies.

The end of Desert Storm did not bring peace to Iraq. One could even say: on the contrary. The Shiite population in the south and the Kurds in the north rose up against the regime and its forces. The insurgency was crushed within months.