Introduction

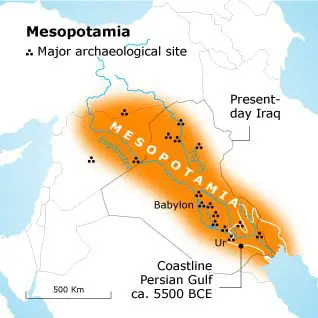

The territory of Iraq largely coincides with the basin of the Dishla and Furat, otherwise known as the Tigris and Euphrates. From antiquity this region has been called Mesopotamia, Greek for ‘Land between Two Rivers’. Over the centuries many civilizations have controlled the region or exerted influence over it, among them the Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Arabs and Turks. The economic basis for the civilizations in Mesopotamia was farming made possible by irrigation, and later also its earnings as a crossroads for trade.

The territory of Iraq largely coincides with the basin of the Dishla and Furat, otherwise known as the Tigris and Euphrates. From antiquity this region has been called Mesopotamia, Greek for ‘Land between Two Rivers’. Over the centuries many civilizations have controlled the region or exerted influence over it, among them the Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Arabs and Turks. The economic basis for the civilizations in Mesopotamia was farming made possible by irrigation, and later also its earnings as a crossroads for trade.

It was about ten thousand years before the beginning of the Christian Era that communities of people in Mesopotamia transformed themselves from hunter-gatherers to agriculturists. The availability of water and fertile soil made this possible. The oldest known civilization in Mesopotamia, that of the Sumerians, reached its flowering about three thousand years before the Christian Era. Thanks to successful agriculture it could achieve a higher degree of social organisation, in the form of a series of city-states.

Two of these city-states, Ur (where Abraham/Ibrahim is said to have been born) and Uruk, are regarded as the first cities in the history of mankind. Both lay at that time on the coast of the Persian Gulf, but through a falling sea level are now about 250 kilometres inland, behind the extensive marshes of southern Iraq. The Sumerians developed the first script, cuneiform, which was written on clay tablets, and which enabled people to exchange information and pass on knowledge and experience to succeeding generations. The epic of king Gilgamesh has been preserved for us in this fashion.

Babylonian and Assyrian Civilizations

About four thousand years ago, Babylonian civilization arose from an amalgamation of the Sumerian and Akkadian kingdoms. Its capital, Babylon, lay south of Baghdad, close to the Euphrates. Under its king, Hammurabi, a well-organized administration was established. The road network was improved to facilitate this administration, and this also stimulated trade. Hammurabi has, however, gone down in history chiefly as the first ruler to have a law code compiled. His goal was to create a legal system that would combat evil and prevent the strong from dominating the weak.

About eight hundred years after the decline of Hammurabi’s kingdom, Babylonian civilization had its second flowering, as Babylonian rulers extended their power far beyond Mesopotamia. Under King Nebuchadnezzar II, the capital, Babylon, grew into a city of a hundred thousand people. Among its many buildings were the royal palace, with its fabled hanging gardens, counted among the seven wonders of the world.

Hammurabi’s kingdom declined and was followed about 1400 BCE by the Assyrian empire, which was strongly militaristic and lasted for eight hundred years. The Assyrian empire, which once again stretched far beyond Mesopotamia, had several capital cities during its history: Assur, Nimrod, and Nineveh, all close to the Tigris, near present-day Mosul.

Persians, Greeks, and Arabs

The fall of the Assyrian empire was followed by about a thousand years of domination by Persians and Greeks. Among their contributions were the cities built in the Greco-Roman and Persian styles, such as Hatra and Ctesiphon. Mesopotamia finally fell into the hands of Arab conquerors in 632 CE. After that, until 1920, it was part of successive Arab and Turkish polities.

Particularly under the Arab Abbasid dynasty (750-1258 CE), architecture and science flourished in the region, and Baghdad was the centre of the world. Little of this illustrious Baghdad is visible today. Baghdad cannot compare, in urban beauty, with Cairo, Jerusalem, or Damascus.

The National Museum

Beginning in the 19th century, Western archaeologists searched Mesopotamia for the remains of the Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, and other civilizations. As was normal in that period, much of the material they found ended up in museums in the West, particularly in Berlin and London. Later finds were housed in Iraq’s National Museum in Baghdad, whose world-famous collection contained about 170,000 objects. But in the first three chaotic weeks after the fall of the regime of Saddam Hussein plunderers and art thieves – some, according to reports, working for international art gangs – rampaged through the museum. To the anger of many Iraqis and the international archaeological community, the US occupying forces did nothing to stop the rampage.

An estimated 15,000 objects were stolen; what could not be carried away was often irreparably damaged. After appeals from various quarters, including Islamic religious authorities, about two-thirds of the missing items have been returned or otherwise located. It is feared that a number of the most important pieces which disappeared will never be located, despite the belated efforts of UNESCO, Interpol, and the FBI.